- The Magazine

- Stay Curious

- The Sciences

- Environment

- Planet Earth

5 Unethical Medical Experiments Brought Out of the Shadows of History

Prisoners and other vulnerable populations often bore the brunt of unethical medical experimentation..

Most people are aware of some of the heinous medical experiments of the past that violated human rights. Participation in these studies was either forced or coerced under false pretenses. Some of the most notorious examples include the experiments by the Nazis, the Tuskegee syphilis study, the Stanford Prison Experiment, and the CIA’s LSD studies.

But there are many other lesser-known experiments on vulnerable populations that have flown under the radar. Study subjects often didn’t — or couldn’t — give consent. Sometimes they were lured into participating with a promise of improved health or a small amount of compensation. Other times, details about the experiment were disclosed but the extent of risks involved weren’t.

This perhaps isn’t surprising, as doctors who conducted these experiments were representative of prevailing attitudes at the time of their work. But unfortunately, even after informed consent was introduced in the 1950s , disregard for the rights of certain populations continued. Some of these researchers’ work did result in scientific advances — but they came at the expense of harmful and painful procedures on unknowing subjects.

Here are five medical experiments of the past that you probably haven’t heard about. They illustrate just how far the ethical and legal guidepost, which emphasizes respect for human dignity above all else, has moved.

The Prison Doctor Who Did Testicular Transplants

From 1913 to 1951, eugenicist Leo Stanley was the chief surgeon at San Quentin State Prison, California’s oldest correctional institution. After performing vasectomies on prisoners, whom he recruited through promises of improved health and vigor, Stanley turned his attention to the emerging field of endocrinology, which involves the study of certain glands and the hormones they regulate. He believed the effects of aging and decreased hormones contributed to criminality, weak morality, and poor physical attributes. Transplanting the testicles of younger men into those who were older would restore masculinity, he thought.

Stanley began by using the testicles of executed prisoners — but he ran into a supply shortage. He solved this by using the testicles of animals, including goats and deer. At first, he physically implanted the testicles directly into the inmates. But that had complications, so he switched to a new plan: He ground up the animal testicles into a paste, which he injected into prisoners’ abdomens. By the end of his time at San Quentin, Stanley did an estimated 10,000 testicular procedures .

The Oncologist Who Injected Cancer Cells Into Patients and Prisoners

During the 1950s and 1960s, Sloan-Kettering Institute oncologist Chester Southam conducted research to learn how people’s immune systems would react when exposed to cancer cells. In order to find out, he injected live HeLa cancer cells into patients, generally without their permission. When patient consent was given, details around the true nature of the experiment were often kept secret. Southam first experimented on terminally ill cancer patients, to whom he had easy access. The result of the injection was the growth of cancerous nodules , which led to metastasis in one person.

Next, Southam experimented on healthy subjects , which he felt would yield more accurate results. He recruited prisoners, and, perhaps not surprisingly, their healthier immune systems responded better than those of cancer patients. Eventually, Southam returned to infecting the sick and arranged to have patients at the Jewish Chronic Disease Hospital in Brooklyn, NY, injected with HeLa cells. But this time, there was resistance. Three doctors who were asked to participate in the experiment refused, resigned, and went public.

The scandalous newspaper headlines shocked the public, and legal proceedings were initiated against Southern. Some in the scientific and medical community condemned his experiments, while others supported him. Initially, Southam’s medical license was suspended for one year, but it was then reduced to a probation. His career continued to be illustrious, and he was subsequently elected president of the American Association for Cancer Research.

The Aptly Named ‘Monster Study’

Pioneering speech pathologist Wendell Johnson suffered from severe stuttering that began early in his childhood. His own experience motivated his focus on finding the cause, and hopefully a cure, for stuttering. He theorized that stuttering in children could be impacted by external factors, such as negative reinforcement. In 1939, under Johnson’s supervision, graduate student Mary Tudor conducted a stuttering experiment, using 22 children at an Iowa orphanage. Half received positive reinforcement. But the other half were ridiculed and criticized for their speech, whether or not they actually stuttered. This resulted in a worsening of speech issues for the children who were given negative feedback.

The study was never published due to the multitude of ethical violations. According to The Washington Post , Tudor was remorseful about the damage caused by the experiment and returned to the orphanage to help the children with their speech. Despite his ethical mistakes, the Wendell Johnson Speech and Hearing Clinic at the University of Iowa bears Johnson's name and is a nod to his contributions to the field.

The Dermatologist Who Used Prisoners As Guinea Pigs

One of the biggest breakthroughs in dermatology was the invention of Retin-A, a cream that can treat sun damage, wrinkles, and other skin conditions. Its success led to fortune and fame for co-inventor Albert Kligman, a dermatologist at the University of Pennsylvania . But Kligman is also known for his nefarious dermatology experiments on prisoners that began in 1951 and continued for around 20 years. He conducted his research on behalf of companies including DuPont and Johnson & Johnson.

Kligman’s work often left prisoners with pain and scars as he used them as study subjects in wound healing and exposed them to deodorants, foot powders, and more for chemical and cosmetic companies. Dow once enlisted Kligman to study the effects of dioxin, a chemical in Agent Orange, on 75 inmates at Pennsylvania's Holmesburg Prison. The prisoners were paid a small amount for their participation but were not told about the potential side effects.

In the University of Pennsylvania’s journal, Almanac , Kligman’s obituary focused on his medical advancements, awards, and philanthropy. There was no acknowledgement of his prison experiments. However, it did mention that as a “giant in the field,” he “also experienced his fair share of controversy.”

The Endocrinologist Who Irradiated Prisoners

When the Atomic Energy Commission wanted to know how radiation affected male reproductive function, they looked to endocrinologist Carl Heller . In a study involving Oregon State Penitentiary prisoners between 1963 and 1973, Heller designed a contraption that would radiate their testicles at varying amounts to see what effect it had, particularly on sperm production. The prisoners also were subjected to repeated biopsies and were required to undergo vasectomies once the experiments concluded.

Although study participants were paid, it raised ethical issues about the potential coercive nature of financial compensation to prison populations. The prisoners were informed about the risks of skin burns, but likely were not told about the possibility of significant pain, inflammation, and the small risk of testicular cancer.

- personal health

- behavior & society

Already a subscriber?

Register or Log In

Keep reading for as low as $1.99!

Sign up for our weekly science updates.

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

- 20 Most Unethical Experiments in Psychology

Humanity often pays a high price for progress and understanding — at least, that seems to be the case in many famous psychological experiments. Human experimentation is a very interesting topic in the world of human psychology. While some famous experiments in psychology have left test subjects temporarily distressed, others have left their participants with life-long psychological issues . In either case, it’s easy to ask the question: “What’s ethical when it comes to science?” Then there are the experiments that involve children, animals, and test subjects who are unaware they’re being experimented on. How far is too far, if the result means a better understanding of the human mind and behavior ? We think we’ve found 20 answers to that question with our list of the most unethical experiments in psychology .

Emma Eckstein

Electroshock Therapy on Children

Operation Midnight Climax

The Monster Study

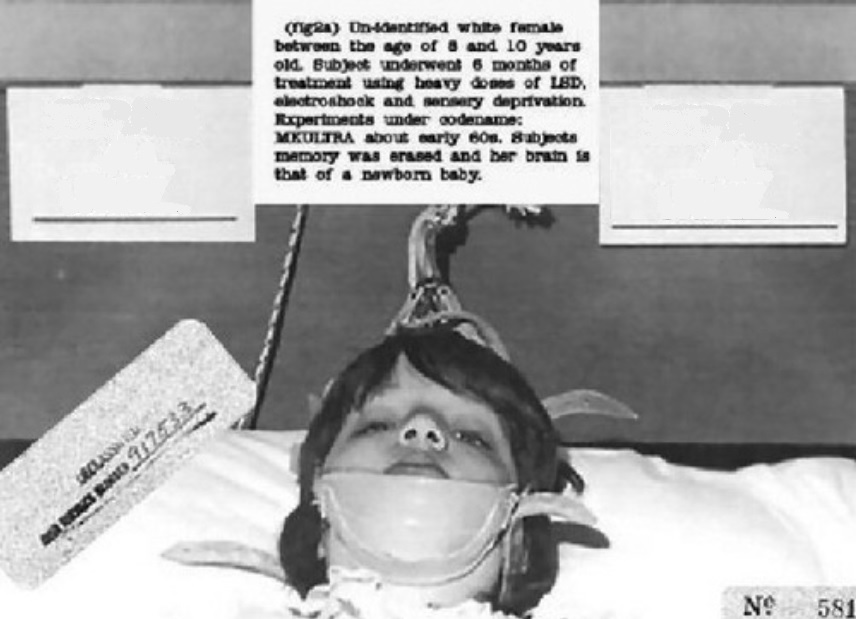

Project MKUltra

The Aversion Project

Unnecessary Sexual Reassignment

Stanford Prison Experiment

Milgram Experiment

The Monkey Drug Trials

Featured Programs

Facial expressions experiment.

Little Albert

Bobo Doll Experiment

The Pit of Despair

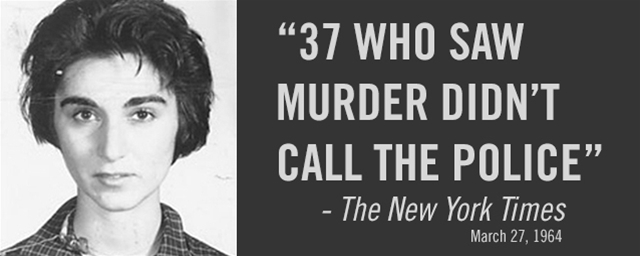

The Bystander Effect

Learned Helplessness Experiment

Racism Among Elementary School Students

UCLA Schizophrenia Experiments

The Good Samaritan Experiment

Robbers Cave Experiment

Related Resources:

- What Careers are in Experimental Psychology?

- What is Experimental Psychology?

- The 25 Most Influential Psychological Experiments in History

- 5 Best Online Ph.D. Marriage and Family Counseling Programs

- Top 5 Online Doctorate in Educational Psychology

- 5 Best Online Ph.D. in Industrial and Organizational Psychology Programs

- Top 10 Online Master’s in Forensic Psychology

- 10 Most Affordable Counseling Psychology Online Programs

- 10 Most Affordable Online Industrial Organizational Psychology Programs

- 10 Most Affordable Online Developmental Psychology Online Programs

- 15 Most Affordable Online Sport Psychology Programs

- 10 Most Affordable School Psychology Online Degree Programs

- Top 50 Online Psychology Master’s Degree Programs

- Top 25 Online Master’s in Educational Psychology

- Top 25 Online Master’s in Industrial/Organizational Psychology

- Top 10 Most Affordable Online Master’s in Clinical Psychology Degree Programs

- Top 6 Most Affordable Online PhD/PsyD Programs in Clinical Psychology

- 50 Great Small Colleges for a Bachelor’s in Psychology

- 50 Most Innovative University Psychology Departments

- The 30 Most Influential Cognitive Psychologists Alive Today

- Top 30 Affordable Online Psychology Degree Programs

- 30 Most Influential Neuroscientists

- Top 40 Websites for Psychology Students and Professionals

- Top 30 Psychology Blogs

- 25 Celebrities With Animal Phobias

- Your Phobias Illustrated (Infographic)

- 15 Inspiring TED Talks on Overcoming Challenges

- 10 Fascinating Facts About the Psychology of Color

- 15 Scariest Mental Disorders of All Time

- 15 Things to Know About Mental Disorders in Animals

- 13 Most Deranged Serial Killers of All Time

Site Information

- About Online Psychology Degree Guide

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Controversial and Unethical Psychology Experiments

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Shereen Lehman, MS, is a healthcare journalist and fact checker. She has co-authored two books for the popular Dummies Series (as Shereen Jegtvig).

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Shereen-Lehman-MS-1000-b8eb65ee2fd1437094f29996bd4f8baa.jpg)

There have been a number of famous psychology experiments that are considered controversial, inhumane, unethical, and even downright cruel—here are five examples. Thanks to ethical codes and institutional review boards, most of these experiments could never be performed today.

At a Glance

Some of the most controversial and unethical experiments in psychology include Harlow's monkey experiments, Milgram's obedience experiments, Zimbardo's prison experiment, Watson's Little Albert experiment, and Seligman's learned helplessness experiment.

These and other controversial experiments led to the formation of rules and guidelines for performing ethical and humane research studies.

Harlow's Pit of Despair

Psychologist Harry Harlow performed a series of experiments in the 1960s designed to explore the powerful effects that love and attachment have on normal development. In these experiments, Harlow isolated young rhesus monkeys, depriving them of their mothers and keeping them from interacting with other monkeys.

The experiments were often shockingly cruel, and the results were just as devastating.

The Experiment

The infant monkeys in some experiments were separated from their real mothers and then raised by "wire" mothers. One of the surrogate mothers was made purely of wire.

While it provided food, it offered no softness or comfort. The other surrogate mother was made of wire and cloth, offering some degree of comfort to the infant monkeys.

Harlow found that while the monkeys would go to the wire mother for nourishment, they preferred the soft, cloth mother for comfort.

Some of Harlow's experiments involved isolating the young monkey in what he termed a "pit of despair." This was essentially an isolation chamber. Young monkeys were placed in the isolation chambers for as long as 10 weeks.

Other monkeys were isolated for as long as a year. Within just a few days, the infant monkeys would begin huddling in the corner of the chamber, remaining motionless.

The Results

Harlow's distressing research resulted in monkeys with severe emotional and social disturbances. They lacked social skills and were unable to play with other monkeys.

They were also incapable of normal sexual behavior, so Harlow devised yet another horrifying device, which he referred to as a "rape rack." The isolated monkeys were tied down in a mating position to be bred.

Not surprisingly, the isolated monkeys also ended up being incapable of taking care of their offspring, neglecting and abusing their young.

Harlow's experiments were finally halted in 1985 when the American Psychological Association passed rules regarding treating people and animals in research.

Milgram's Shocking Obedience Experiments

Isabelle Adam/Flickr/CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

If someone told you to deliver a painful, possibly fatal shock to another human being, would you do it? The vast majority of us would say that we absolutely would never do such a thing, but one controversial psychology experiment challenged this basic assumption.

Social psychologist Stanley Milgram conducted a series of experiments to explore the nature of obedience . Milgram's premise was that people would often go to great, sometimes dangerous, or even immoral, lengths to obey an authority figure.

The Experiments

In Milgram's experiment, subjects were ordered to deliver increasingly strong electrical shocks to another person. While the person in question was simply an actor who was pretending, the subjects themselves fully believed that the other person was actually being shocked.

The voltage levels started out at 30 volts and increased in 15-volt increments up to a maximum of 450 volts. The switches were also labeled with phrases including "slight shock," "medium shock," and "danger: severe shock." The maximum shock level was simply labeled with an ominous "XXX."

The results of the experiment were nothing short of astonishing. Many participants were willing to deliver the maximum level of shock, even when the person pretending to be shocked was begging to be released or complaining of a heart condition.

Milgram's experiment revealed stunning information about the lengths that people are willing to go in order to obey, but it also caused considerable distress for the participants involved.

Zimbardo's Simulated Prison Experiment

Darrin Klimek / Getty Images

Psychologist Philip Zimbardo went to high school with Stanley Milgram and had an interest in how situational variables contribute to social behavior.

In his famous and controversial experiment, he set up a mock prison in the basement of the psychology department at Stanford University. Participants were then randomly assigned to be either prisoners or guards. Zimbardo himself served as the prison warden.

The researchers attempted to make a realistic situation, even "arresting" the prisoners and bringing them into the mock prison. Prisoners were placed in uniforms, while the guards were told that they needed to maintain control of the prison without resorting to force or violence.

When the prisoners began to ignore orders, the guards began to utilize tactics that included humiliation and solitary confinement to punish and control the prisoners.

While the experiment was originally scheduled to last two full weeks it had to be halted after just six days. Why? Because the prison guards had started abusing their authority and were treating the prisoners cruelly. The prisoners, on the other hand, started to display signs of anxiety and emotional distress.

It wasn't until a graduate student (and Zimbardo's future wife) Christina Maslach visited the mock prison that it became clear that the situation was out of control and had gone too far. Maslach was appalled at what was going on and voiced her distress. Zimbardo then decided to call off the experiment.

Zimbardo later suggested that "although we ended the study a week earlier than planned, we did not end it soon enough."

Watson and Rayner's Little Albert Experiment

If you have ever taken an Introduction to Psychology class, then you are probably at least a little familiar with Little Albert.

Behaviorist John Watson and his assistant Rosalie Rayner conditioned a boy to fear a white rat, and this fear even generalized to other white objects including stuffed toys and Watson's own beard.

Obviously, this type of experiment is considered very controversial today. Frightening an infant and purposely conditioning the child to be afraid is clearly unethical.

As the story goes, the boy and his mother moved away before Watson and Rayner could decondition the child, so many people have wondered if there might be a man out there with a mysterious phobia of furry white objects.

Controversy

Some researchers have suggested that the boy at the center of the study was actually a cognitively impaired boy who ended up dying of hydrocephalus when he was just six years old. If this is true, it makes Watson's study even more disturbing and controversial.

However, more recent evidence suggests that the real Little Albert was actually a boy named William Albert Barger.

Seligman's Look Into Learned Helplessness

During the late 1960s, psychologists Martin Seligman and Steven F. Maier conducted experiments that involved conditioning dogs to expect an electrical shock after hearing a tone. Seligman and Maier observed some unexpected results.

When initially placed in a shuttle box in which one side was electrified, the dogs would quickly jump over a low barrier to escape the shocks. Next, the dogs were strapped into a harness where the shocks were unavoidable.

After being conditioned to expect a shock that they could not escape, the dogs were once again placed in the shuttlebox. Instead of jumping over the low barrier to escape, the dogs made no efforts to escape the box.

Instead, they simply lay down, whined and whimpered. Since they had previously learned that no escape was possible, they made no effort to change their circumstances. The researchers called this behavior learned helplessness .

Seligman's work is considered controversial because of the mistreating the animals involved in the study.

Impact of Unethical Experiments in Psychology

Many of the psychology experiments performed in the past simply would not be possible today, thanks to ethical guidelines that direct how studies are performed and how participants are treated. While these controversial experiments are often disturbing, we can still learn some important things about human and animal behavior from their results.

Perhaps most importantly, some of these controversial experiments led directly to the formation of rules and guidelines for performing psychology studies.

Blum, Deborah. Love at Goon Park: Harry Harlow and the science of affection . New York: Basic Books; 2011.

Sperry L. Mental Health and Mental Disorders: an Encyclopedia of Conditions, Treatments, and Well-Being . Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood, an imprint of ABC-CLIO, LLC; 2016.

Marcus S. Obedience to Authority An Experimental View. By Stanley Milgram. illustrated . New York: Harper &. The New York Times.

Le Texier T. Debunking the Stanford Prison Experiment . Am Psychol . 2019;74(7):823‐839. doi:10.1037/amp0000401

Fridlund AJ, Beck HP, Goldie WD, Irons G. Little Albert: A neurologically impaired child . Hist Psychol. 2012;15(4):302-27. doi:10.1037/a0026720

Powell RA, Digdon N, Harris B, Smithson C. Correcting the record on Watson, Rayner, and Little Albert: Albert Barger as "psychology's lost boy" . Am Psychol . 2014;69(6):600‐611. doi:10.1037/a0036854

Seligman ME. Learned helplessness . Annu Rev Med . 1972;23:407‐412. doi:10.1146/annurev.me.23.020172.002203

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

10 Psychological Experiments That Could Never Happen Today

Nowadays, the American Psychological Association has a Code of Conduct in place when it comes to ethics in psychological experiments. Experimenters must adhere to various rules pertaining to everything from confidentiality to consent to overall beneficence. Review boards are in place to enforce these ethics. But the standards were not always so strict, which is how some of the most famous studies in psychology came about.

1. The Little Albert Experiment

At Johns Hopkins University in 1920, John B. Watson conducted a study of classical conditioning, a phenomenon that pairs a conditioned stimulus with an unconditioned stimulus until they produce the same result. This type of conditioning can create a response in a person or animal towards an object or sound that was previously neutral. Classical conditioning is commonly associated with Ivan Pavlov, who rang a bell every time he fed his dog until the mere sound of the bell caused his dog to salivate.

Watson tested classical conditioning on a 9-month-old baby he called Albert B. The young boy started the experiment loving animals, particularly a white rat. Watson started pairing the presence of the rat with the loud sound of a hammer hitting metal. Albert began to develop a fear of the white rat as well as most animals and furry objects. The experiment is considered particularly unethical today because Albert was never desensitized to the phobias that Watson produced in him. (The child died of an unrelated illness at age 6, so doctors were unable to determine if his phobias would have lasted into adulthood.)

2. Asch Conformity Experiments

Solomon Asch tested conformity at Swarthmore College in 1951 by putting a participant in a group of people whose task was to match line lengths. Each individual was expected to announce which of three lines was the closest in length to a reference line. But the participant was placed in a group of actors, who were all told to give the correct answer twice then switch to each saying the same incorrect answer. Asch wanted to see whether the participant would conform and start to give the wrong answer as well, knowing that he would otherwise be a single outlier.

Thirty-seven of the 50 participants agreed with the incorrect group despite physical evidence to the contrary. Asch used deception in his experiment without getting informed consent from his participants, so his study could not be replicated today.

3. The Bystander Effect

Some psychological experiments that were designed to test the bystander effect are considered unethical by today’s standards. In 1968, John Darley and Bibb Latané developed an interest in crime witnesses who did not take action. They were particularly intrigued by the murder of Kitty Genovese , a young woman whose murder was witnessed by many, but still not prevented.

The pair conducted a study at Columbia University in which they would give a participant a survey and leave him alone in a room to fill out the paper. Harmless smoke would start to seep into the room after a short amount of time. The study showed that the solo participant was much faster to report the smoke than participants who had the exact same experience, but were in a group.

The studies became progressively unethical by putting participants at risk of psychological harm. Darley and Latané played a recording of an actor pretending to have a seizure in the headphones of a person, who believed he or she was listening to an actual medical emergency that was taking place down the hall. Again, participants were much quicker to react when they thought they were the sole person who could hear the seizure.

4. The Milgram Experiment

Yale psychologist Stanley Milgram hoped to further understand how so many people came to participate in the cruel acts of the Holocaust. He theorized that people are generally inclined to obey authority figures, posing the question , “Could it be that Eichmann and his million accomplices in the Holocaust were just following orders? Could we call them all accomplices?” In 1961, he began to conduct experiments of obedience.

Participants were under the impression that they were part of a study of memory . Each trial had a pair divided into “teacher” and “learner,” but one person was an actor, so only one was a true participant. The drawing was rigged so that the participant always took the role of “teacher.” The two were moved into separate rooms and the “teacher” was given instructions. He or she pressed a button to shock the “learner” each time an incorrect answer was provided. These shocks would increase in voltage each time. Eventually, the actor would start to complain followed by more and more desperate screaming. Milgram learned that the majority of participants followed orders to continue delivering shocks despite the clear discomfort of the “learner.”

Had the shocks existed and been at the voltage they were labeled, the majority would have actually killed the “learner” in the next room. Having this fact revealed to the participant after the study concluded would be a clear example of psychological harm.

5. Harlow’s Monkey Experiments

In the 1950s, Harry Harlow of the University of Wisconsin tested infant dependency using rhesus monkeys in his experiments rather than human babies. The monkey was removed from its actual mother which was replaced with two “mothers,” one made of cloth and one made of wire. The cloth “mother” served no purpose other than its comforting feel whereas the wire “mother” fed the monkey through a bottle. The monkey spent the majority of his day next to the cloth “mother” and only around one hour a day next to the wire “mother,” despite the association between the wire model and food.

Harlow also used intimidation to prove that the monkey found the cloth “mother” to be superior. He would scare the infants and watch as the monkey ran towards the cloth model. Harlow also conducted experiments which isolated monkeys from other monkeys in order to show that those who did not learn to be part of the group at a young age were unable to assimilate and mate when they got older. Harlow’s experiments ceased in 1985 due to APA rules against the mistreatment of animals as well as humans . However, Department of Psychiatry Chair Ned H. Kalin, M.D. of the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health has recently begun similar experiments that involve isolating infant monkeys and exposing them to frightening stimuli. He hopes to discover data on human anxiety, but is meeting with resistance from animal welfare organizations and the general public.

6. Learned Helplessness

The ethics of Martin Seligman’s experiments on learned helplessness would also be called into question today due to his mistreatment of animals. In 1965, Seligman and his team used dogs as subjects to test how one might perceive control. The group would place a dog on one side of a box that was divided in half by a low barrier. Then they would administer a shock, which was avoidable if the dog jumped over the barrier to the other half. Dogs quickly learned how to prevent themselves from being shocked.

Seligman’s group then harnessed a group of dogs and randomly administered shocks, which were completely unavoidable. The next day, these dogs were placed in the box with the barrier. Despite new circumstances that would have allowed them to escape the painful shocks, these dogs did not even try to jump over the barrier; they only cried and did not jump at all, demonstrating learned helplessness.

7. Robbers Cave Experiment

Muzafer Sherif conducted the Robbers Cave Experiment in the summer of 1954, testing group dynamics in the face of conflict. A group of preteen boys were brought to a summer camp, but they did not know that the counselors were actually psychological researchers. The boys were split into two groups, which were kept very separate. The groups only came into contact with each other when they were competing in sporting events or other activities.

The experimenters orchestrated increased tension between the two groups, particularly by keeping competitions close in points. Then, Sherif created problems, such as a water shortage, that would require both teams to unite and work together in order to achieve a goal. After a few of these, the groups became completely undivided and amicable.

Though the experiment seems simple and perhaps harmless, it would still be considered unethical today because Sherif used deception as the boys did not know they were participating in a psychological experiment. Sherif also did not have informed consent from participants.

8. The Monster Study

At the University of Iowa in 1939, Wendell Johnson and his team hoped to discover the cause of stuttering by attempting to turn orphans into stutterers. There were 22 young subjects, 12 of whom were non-stutterers. Half of the group experienced positive teaching whereas the other group dealt with negative reinforcement. The teachers continually told the latter group that they had stutters. No one in either group became stutterers at the end of the experiment, but those who received negative treatment did develop many of the self-esteem problems that stutterers often show. Perhaps Johnson’s interest in this phenomenon had to do with his own stutter as a child , but this study would never pass with a contemporary review board.

Johnson’s reputation as an unethical psychologist has not caused the University of Iowa to remove his name from its Speech and Hearing Clinic .

9. Blue Eyed versus Brown Eyed Students

Jane Elliott was not a psychologist, but she developed one of the most famously controversial exercises in 1968 by dividing students into a blue-eyed group and a brown-eyed group. Elliott was an elementary school teacher in Iowa, who was trying to give her students hands-on experience with discrimination the day after Martin Luther King Jr. was shot, but this exercise still has significance to psychology today. The famous exercise even transformed Elliott’s career into one centered around diversity training.

After dividing the class into groups, Elliott would cite phony scientific research claiming that one group was superior to the other. Throughout the day, the group would be treated as such. Elliott learned that it only took a day for the “superior” group to turn crueler and the “inferior” group to become more insecure. The blue eyed and brown eyed groups then switched so that all students endured the same prejudices.

Elliott’s exercise (which she repeated in 1969 and 1970) received plenty of public backlash, which is probably why it would not be replicated in a psychological experiment or classroom today. The main ethical concerns would be with deception and consent, though some of the original participants still regard the experiment as life-changing .

10. The Stanford Prison Experiment

In 1971, Philip Zimbardo of Stanford University conducted his famous prison experiment, which aimed to examine group behavior and the importance of roles. Zimbardo and his team picked a group of 24 male college students who were considered “healthy,” both physically and psychologically. The men had signed up to participate in a “ psychological study of prison life ,” which would pay them $15 per day. Half were randomly assigned to be prisoners and the other half were assigned to be prison guards. The experiment played out in the basement of the Stanford psychology department where Zimbardo’s team had created a makeshift prison. The experimenters went to great lengths to create a realistic experience for the prisoners, including fake arrests at the participants’ homes.

The prisoners were given a fairly standard introduction to prison life, which included being deloused and assigned an embarrassing uniform. The guards were given vague instructions that they should never be violent with the prisoners, but needed to stay in control. The first day passed without incident, but the prisoners rebelled on the second day by barricading themselves in their cells and ignoring the guards. This behavior shocked the guards and presumably led to the psychological abuse that followed. The guards started separating “good” and “bad” prisoners, and doled out punishments including push ups, solitary confinement, and public humiliation to rebellious prisoners.

Zimbardo explained , “In only a few days, our guards became sadistic and our prisoners became depressed and showed signs of extreme stress.” Two prisoners dropped out of the experiment; one eventually became a psychologist and a consultant for prisons . The experiment was originally supposed to last for two weeks, but it ended early when Zimbardo’s future wife, psychologist Christina Maslach, visited the experiment on the fifth day and told him , “I think it’s terrible what you’re doing to those boys.”

Despite the unethical experiment, Zimbardo is still a working psychologist today. He was even honored by the American Psychological Association with a Gold Medal Award for Life Achievement in the Science of Psychology in 2012 .

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

StatPearls [Internet].

Research ethics.

Jennifer M. Barrow ; Grace D. Brannan ; Paras B. Khandhar .

Affiliations

Last Update: September 18, 2022 .

- Introduction

Multiple examples of unethical research studies conducted in the past throughout the world have cast a significant historical shadow on research involving human subjects. Examples include the Tuskegee Syphilis Study from 1932 to 1972, Nazi medical experimentation in the 1930s and 1940s, and research conducted at the Willowbrook State School in the 1950s and 1960s. [1] As the aftermath of these practices, wherein uninformed and unaware patients were exposed to disease or subject to other unproven treatments, became known, the need for rules governing the design and implementation of human-subject research protocols became very evident.

The first such ethical code for research was the Nuremberg Code, arising in the aftermath of Nazi research atrocities brought to light in the post-World War II Nuremberg Trials. [1] This set of international research standards sought to prevent gross research misconduct and abuse of vulnerable and unwitting research subjects by establishing specific human subject protective factors. A direct descendant of this code was drafted in 1978 in the United States, known as the Belmont Report, and this legislation forms the backbone of regulation of clinical research in the USA since its adoption. [2] The Belmont Report contains 3 basic ethical principles:

- Respect for persons

- Beneficence

Additionally, the Belmont Report details research-based protective applications for informed consent, risk/benefit assessment, and participant selection. [3]

- Issues of Concern

The first protective principle stemming from the 1978 Belmont Report is the principle of Respect for Persons, also known as human dignity. [2] This dictates researchers must work to protect research participants' autonomy while also ensuring full disclosure of factors surrounding the study, including potential harms and benefits. According to the Belmont Report, "an autonomous person is an individual capable of deliberation about personal goals and acting under the direction of such deliberation." [1]

To ensure participants have the autonomous right to self-determination, researchers must ensure that potential participants understand that they have the right to decide whether or not to participate in research studies voluntarily and that declining to participate in any research does not affect in any way their access to current or subsequent care. Also, self-determined participants must be able to ask the researcher questions and comprehend the questions asked by the researcher. Researchers must also inform participants that they may stop participating in the study without fear of penalty. [4] As noted in the Belmont Report definition above, not all individuals can be autonomous concerning research participation. Whether because of the individual's developmental level or because of various illnesses or disabilities, some individuals require special research protections that may involve exclusion from research activities that can cause potential harm or appointing a third-party guardian to oversee the participation of such vulnerable persons. [5]

Researchers must also ensure they do not coerce potential participants into agreeing to participate in studies. Coercion refers to threats of penalty, whether implied or explicit, if participants decline to participate or opt out of a study. Additionally, giving potential participants extreme rewards for agreeing to participate can be a form of coercion. The rewards may provide an enticing enough incentive that the participant feels they need to participate. In contrast, they would otherwise have declined if such a reward were not offered. While researchers often use various rewards and incentives in studies, they must carefully review this possibility of coercion. Some incentives may pressure potential participants into joining a study, thereby stripping participants of complete self-determination. [3]

An additional aspect of respecting potential participants' self-determination is to ensure that researchers have fully disclosed information about the study and explained the voluntary nature of participation (including the right to refuse without repercussion) and possible benefits and risks related to study participation. A potential participant cannot make a truly informed decision without complete information. This aspect of the Belmont Report can be troublesome for some researchers based on their study designs and research questions. Noted biases related to reactivity may occur when study participants know the exact guiding research questions and purposes. Some researchers may avoid reactivity biases using covert data collection methods or masking critical study information. Masking frequently occurs in pharmaceutical trials with placebos because knowledge of placebo receipt can affect study outcomes. However, masking and concealed data collection methods may not fully respect participants' rights to autonomy and the associated informed consent process. Any researcher considering hidden data collection or masking of some research information from participants must present their plans to an Institutional Review Board (IRB) for oversight, as well as explain the potential masking to prospective patients in the consent process (ie, explaining to potential participants in a medication trial that they are randomly assigned either the medication or a placebo). The IRB determines if studies warrant concealed data collection or masking methods in light of the research design, methods, and study-specific protections. [6]

The second Belmont Report principle is the principle of beneficence. Beneficence refers to acting in such a way to benefit others while promoting their welfare and safety. [7] Although not explicitly mentioned by name, the biomedical ethical principle of nonmaleficence (not harm) also appears within the Belmont Report's section on beneficence. The beneficence principle includes 2 specific research aspects:

- Participants' right to freedom from harm and discomfort

- Participants' rights to protection from exploitation [8]

Before seeking IRB approval and conducting a study, researchers must analyze potential risks and benefits to research participants. Examples of possible participant risks include physical harm, loss of privacy, unforeseen side effects, emotional distress or embarrassment, monetary costs, physical discomfort, and loss of time. Possible benefits include access to a potentially valuable intervention, increased understanding of a medical condition, and satisfaction with helping others with similar issues. [8] These potential risks and benefits should explicitly appear in the written informed consent document used in the study. Researchers must implement specific protections to minimize discomfort and harm to align with the principle of beneficence. Under the principle of beneficence, researchers must also protect participants from exploitation. Any information provided by participants through their study involvement must be protected.

The final principle contained in the Belmont Report is the principle of justice, which pertains to participants' right to fair treatment and right to privacy. The selection of the types of participants desired for a research study should be guided by research questions and requirements not to exclude any group and to be as representative of the overall target population as possible. Researchers and IRBs must scrutinize the selection of research participants to determine whether researchers are systematically selecting some groups (eg, participants receiving public financial assistance, specific ethnic and racial minorities, or institutionalized) because of their vulnerability or ease of access. The right to fair treatment also relates to researchers treating those who refuse to participate in a study fairly without prejudice. [3]

The right to privacy also falls under the Belmont Report's principle of justice. Researchers must keep any shared information in their strictest confidence. Upholding the right to privacy often involves procedures for anonymity or confidentiality. For participants' data to be completely anonymous, the researcher cannot have the ability to connect the participants to their data. The study is no longer anonymous if researchers can make participant-data connections, even if they use codes or pseudonyms instead of personal identifiers. Instead, researchers are providing participant confidentiality. Various methods can help researchers assure confidentiality, including locking any participant identifying data and substituting code numbers instead of names, with a correlation key available only to a safety or oversight functionary in an emergency but not readily available to researchers. [3]

- Clinical Significance

One of the most common safeguards for the ethical conduct of research involves using external reviewers, such as an Institutional Review Board (IRB). Researchers seeking to begin a study must submit a full research proposal to the IRB, which includes specific data collection instruments, research advertisements, and informed consent documentation. The IRB may perform a complete or expedited review depending on the nature of the study and the risks involved. Researchers cannot contact potential participants or start collecting data until they obtain full IRB approval. Sometimes, multi-site studies require approvals from several IRBs, which may have different forms and review processes. [3]

A significant study aspect of interest to IRB members is using participants from vulnerable groups. Vulnerable groups may include individuals who cannot give fully informed consent or those individuals who may be at elevated risk of unplanned side effects. Examples of vulnerable participants include pregnant women, children younger than the age of consent, terminally ill individuals, institutionalized individuals, and those with mental or emotional disabilities. In the case of minors, assent is also an element that must be addressed per Subpart D of the Code of Federal Regulations, 45 CFR 46.402, which defines consent as "a child's affirmative agreement to participate in research; mere failure to object should not, absent affirmative agreement, be construed as assent." [9] There is a lack in the literature on when minors can understand research, although current research suggests that the age by which a minor could assent is around 14. [10] Anytime researchers include vulnerable groups in their studies, they must have extra safeguards to uphold the Belmont Report's ethical principles, especially beneficence. [3]

- Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Research ethics is a foundational principle of modern medical research across all disciplines. The overarching body, the IRB, is intentionally comprised of experts across various disciplines, including ethicists, social workers, physicians, nurses, other scientific researchers, counselors, mental health professionals, and advocates for vulnerable subjects. There is also often a legal expert on the panel or available to discuss any questions regarding the legality or ramifications of studies.

- Review Questions

- Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

- Comment on this article.

Disclosure: Jennifer Barrow declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Grace Brannan declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Paras Khandhar declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

This book is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ), which permits others to distribute the work, provided that the article is not altered or used commercially. You are not required to obtain permission to distribute this article, provided that you credit the author and journal.

- Cite this Page Barrow JM, Brannan GD, Khandhar PB. Research Ethics. [Updated 2022 Sep 18]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

In this Page

Bulk download.

- Bulk download StatPearls data from FTP

Related information

- PMC PubMed Central citations

- PubMed Links to PubMed

Recent Activity

- Research Ethics - StatPearls Research Ethics - StatPearls

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

- Search Grant Programs

- Application Review Process

- Manage Your Award

- Grantee Communications Toolkit

- NEH International Opportunities

- Workshops, Resources, & Tools

- Search All Past Awards

- Divisions and Offices

- Professional Development

- Sign Up to Be a Panelist

- Equity Action Plan

- Emergency and Disaster Relief

- States and Jurisdictions

- Featured NEH-Funded Projects

- Humanities Magazine

- Information for Native and Indigenous Communities

- Information for Pacific Islanders

- Search Our Work

- American Tapestry

- International Engagement

- Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative

- Humanities Perspectives on Artificial Intelligence

- Pacific Islands Cultural Initiative

- United We Stand: Connecting Through Culture

- A More Perfect Union

- NEH Leadership

- Open Government

- Contact NEH

- Press Releases

- NEH in the News

The Painful Legacy of Human Experimentation

Research funded by a 1995 neh grant to wellesley college’s susan reverby became the basis for long-term scholarly engagement with the notorious “tuskegee” syphilis study, and lead to the discovery of a disturbing chapter in the history of human experimentation in guatemala..

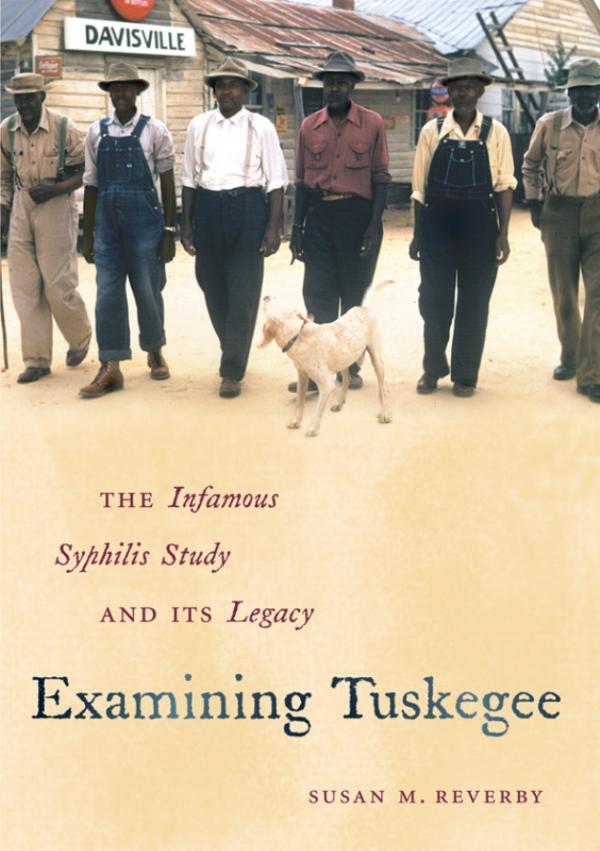

Susan M. Reverby's Examining Tuskegee (UNC Press 2009) has won multiple awards, including the 2011 James F. Sulzby Award from the Alabama Historical Association, and the 2010 Arthur J. Viseltear Award from the American Public Health Association.

Credit: Copyright © 2011 by the University of North Carolina Press.

An NEH grant in 1995 helped Susan M. Reverby of Wellesley College conduct her award-winning research on the infamous "Tuskegee" study.

Credit: Wellesley College

Before 2010, Susan Reverby was perhaps best known for her work investigating the notorious 40-year study of “untreated syphilis in the male Negro,” during which members of the U.S. Public Health Service (PHS) observed (but did not attempt to treat) the effects of late-stage syphilis in over 400 African American men living around the town of Tuskegee in Macon County, Georgia. Reverby’s research into those experiments, commonly known as the “Tuskegee” study, has already spawned two widely acclaimed books: Tuskegee’s Truths (ed. 2000, UNC Press) and Examining Tuskegee (2009, UNC Press).

And it was while combing through the archives of one of the study’s chief practitioners, Dr. John Cutler of the PHS, that Reverby, an historian of American women, medicine, and nursing at Wellesley College, discovered evidence of a disturbing offshoot of PHS syphilis experimentation, this time in Guatemala. The experiments, conducted from 1946 to 1948 on men and women in Guatemalan army barracks, prisons, and asylums, involved more extreme practices than those associated with the Tuskegee study, including deliberate, painful methods for infecting subjects with syphilis. (Despite popular claims to the contrary, “Tuskegee study” scientists did not - and as Reverby argues, likely could not – surreptitiously infect their American subjects with the sexually transmitted disease.)

Alarmed by the shocking nature of her discovery, Reverby alerted contacts at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control, where the late David Sencer, then the director of the CDC, took her findings seriously and quickly commissioned a CDC study of the same archival material that confirmed her research. Reverby’s report on the syphilis experiments in Guatemala, which appeared in the Journal of Policy History in January 2011, includes an addendum about the serious investigative measures taken by the U.S. in the wake of her discovery. On September 16, 2011, the President’s Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues published a 220-page report on the history and implications of the PHS experiments, and the Commission has used the case as a starting point for further conversation about the ethics of human medical experimentation.

Considering the major influence her research has had, it is difficult to believe that Reverby’s initial proposal to publish her work fell flat. Reverby had intended that the research she conducted in the 1990s on the Tuskegee study, funded in part by a $30,000 NEH grant, would form the heart of a book project on nurse Eunice Rivers Laurie, a controversial figure in the history of the Tuskegee syphilis experiments. Questions surrounding the role of Rivers, a nurse who worked with PHS doctors and administrators over the entire 40-year course of the study, have long fascinated the scholars and the public. But at a fateful meeting in a coffee shop New York City, a disappointed Reverby listened as a literary agent told her that her proposal could not sustain a book-length treatment. “It was a terrible moment,” Reverby said.

Reverby soon found a home for her research on Nurse Rivers in a volume she edited that brought together archival documents and scholarly articles dealing with multiple aspects of the history and reception of the Tuskegee study ( Tuskegee’s Truths , ed. 2000). In 2009, she published Examining Tuskegee , a penetrating look into the historical circumstances of the study, and a sober exploration of the complicated public legacy of “Tuskegee” in America. The book earned widespread praise and won multiple awards, including the 2011 James F. Sulzby Award from the Alabama Historical Association, the 2010 Arthur J. Viseltear Award from the American Public Health Association, and the 2010 Ralph Waldo Emerson Award of the Phi Beta Kappa Society.

Reverby plans to explore further the ways that the stories of public health scandals are told in a future monograph, provisionally titled “Escaping Melodrama.” This latest addition to her long-term and influential research into the history of human experimentation is further proof that a modest investment by the NEH can pay dividends for years to come. Reflecting on the long path of her research on the Tuskegee study and its aftermath, Reverby expressed gratitude for the role that her NEH grant played: “At a small liberal arts college, the workload and emphasis on teaching and service can be so intense, so it’s very important to find funding to make research sabbaticals viable.”

Funding information

Scholar Susan Reverby was awarded a $30,000 NEH fellowship in 1995 to research the history of the Tuskegee syphilis experiment for a book on nurse Eunice Rivers.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- NEWS FEATURE

- 18 July 2023

Medicine is plagued by untrustworthy clinical trials. How many studies are faked or flawed?

- Richard Van Noorden 0

Richard Van Noorden is a features editor at Nature in London.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

How many clinical-trial studies in medical journals are fake or fatally flawed? In October 2020, John Carlisle reported a startling estimate 1 .

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Nature 619 , 454-458 (2023)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-02299-w

Carlisle, J. B. Anaesthesia 76 , 472–479 (2021).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Roberts, I., Smith, R. & Evans, S. BMJ 334 , 392 (2007).

Avenell, A., Bolland, M. J., Gamble, G. D. & Grey, A. Account. Res . https://doi.org/10.1080/08989621.2022.2082290 (2022).

Article Google Scholar

Popp, M. et al. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 6 , CD015017 (2022).

Ker, K., Shakur, H. & Roberts, I. BJOG 123 , 1745–1752 (2016).

WOMAN Trial Collaborators. Lancet 389 , 2105–2116 (2017).

Bellos, I. & Pergialiotis, V. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 226 , 510–523 (2021).

Pacheco, L. D. et al. N. Engl. J. Med. 388 , 1365–1375 (2023).

Sotiriadis, A. et al. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 8 , CD006614 (2018).

Sotiriadis, A. et al. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 8 , CD006614 (2021).

Wilson, A. et al. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 8 , CD014978 (2022).

Boughton, S. L., Wilkinson, J. & Bero, L. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 6 , ED000152 (2021).

Roberts, I. et al. BMJ 350 , h2463 (2015).

Download references

Reprints and permissions

Related Articles

- Research data

- Medical research

The huge protein database that spawned AlphaFold and biology’s AI revolution

News Q&A 18 OCT 24

Can AI shake-up translational research?

Spotlight 16 OCT 24

Six tips for going public with your lab’s software

Technology Feature 14 OCT 24

Do stem-cell transplants increase cancer risk? Long-lived recipients offer clues

News 25 OCT 24

Long-term lineage commitment in hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy

Article 23 OCT 24

Disease background influences fate of transplanted stem cells

News & Views 23 OCT 24

Assistant Professor

Faculty positions at the Assistant Professor level in Cancer, Cardiovascular, Metabolic Health, Brain, Mind, and Behavior.

Chicago, Illinois

Northwestern University Recruitment to Transform Under-Representation and achieve Equity – an NIH FIRST Award

Instructional Faculty Positions

The Biological and Environmental Science and Engineering (BESE) Division at King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST), a globally ...

Saudi Arabia (SA)

King Abdullah University of Science and Technology

Postdoctoral Fellow (all genders) with focus on Thromboinflammation

Postdoctoral Fellow (all genders) with focus on Thromboinflammation | Fulltime/Parttime | Temporary | Arbeitsort: Hamburg- Eppendorf

Hamburg (DE)

Universitätsklinikum Hamburg-Eppendorf

Assistant Professor of Molecular Genetics and Microbiology

The Department of Molecular Genetics and Microbiology at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine (http://mgm.unm.edu/index.html) is seeking...

University of New Mexico, Albuquerque

Assistant/Associate/Professor of Pediatrics (Neonatology)

Join the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Illinois College of Medicine Peoria as a full-time Neonatologist.

Peoria, Illinois

University of Illinois College of Medicine Peoria

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

COMMENTS

Some of the most notorious examples include the experiments by the Nazis, the Tuskegee syphilis study, the Stanford Prison Experiment, and the CIA’s LSD studies. But there are many other lesser-known experiments on vulnerable populations that have flown under the radar.

From 1953 to 1973, the United States government conducted a series of unethical experiments meant to figure out the best ways to manipulate the mental states of citizens, and then to “develop chemical materials capable of employment in clandestine operations.”.

Some of the most controversial and unethical experiments in psychology include Harlow's monkey experiments, Milgram's obedience experiments, Zimbardo's prison experiment, Watson's Little Albert experiment, and Seligman's learned helplessness experiment.

The need for retribution and compensation is found in a famously unethical experiment: the Tuskegee syphilis study. Syphilis was seen as a major health problem in the 1920s, so in 1932, the...

Controversy is essential to scientific progress - here we digest ten of the most controversial studies in psychology’s history.

Some psychological experiments that were designed to test the bystander effect are considered unethical by today’s standards.

Multiple examples of unethical research studies conducted in the past throughout the world have cast a significant historical shadow on research involving human subjects. Examples include the Tuskegee Syphilis Study from 1932 to 1972, Nazi medical experimentation in the 1930s and 1940s, and research conducted at the Willowbrook State School in ...

The experiments, conducted from 1946 to 1948 on men and women in Guatemalan army barracks, prisons, and asylums, involved more extreme practices than those associated with the Tuskegee study, including deliberate, painful methods for infecting subjects with syphilis. (Despite popular claims to the contrary, “Tuskegee study” scientists did ...

18 July 2023. Medicine is plagued by untrustworthy clinical trials. How many studies are faked or flawed? Investigations suggest that, in some fields, at least one-quarter of clinical trials...

Some of history’s most controversial psychology studies helped drive extensive protections for human research participants. Some say those reforms went too far.