S371 Social Work Research - Jill Chonody: What is Quantitative Research?

- Choosing a Topic

- Choosing Search Terms

- What is Quantitative Research?

- Requesting Materials

Quantitative Research in the Social Sciences

This page is courtesy of University of Southern California: http://libguides.usc.edu/content.php?pid=83009&sid=615867

Quantitative methods emphasize objective measurements and the statistical, mathematical, or numerical analysis of data collected through polls, questionnaires, and surveys, or by manipulating pre-existing statistical data using computational techniques . Quantitative research focuses on gathering numerical data and generalizing it across groups of people or to explain a particular phenomenon.

Babbie, Earl R. The Practice of Social Research . 12th ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage, 2010; Muijs, Daniel. Doing Quantitative Research in Education with SPSS . 2nd edition. London: SAGE Publications, 2010.

Characteristics of Quantitative Research

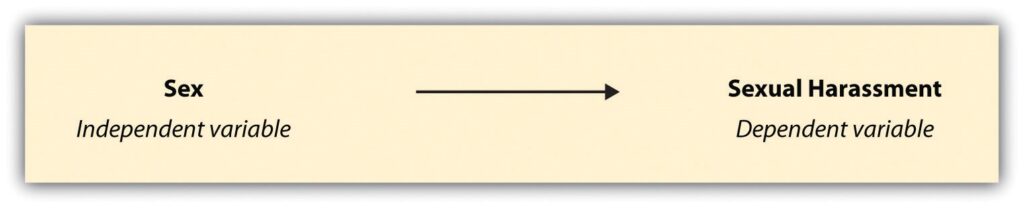

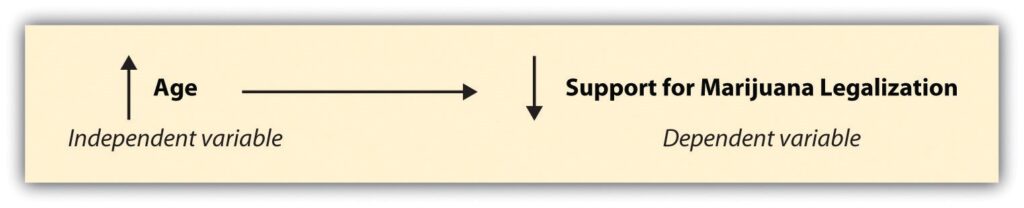

Your goal in conducting quantitative research study is to determine the relationship between one thing [an independent variable] and another [a dependent or outcome variable] within a population. Quantitative research designs are either descriptive [subjects usually measured once] or experimental [subjects measured before and after a treatment]. A descriptive study establishes only associations between variables; an experimental study establishes causality.

Quantitative research deals in numbers, logic, and an objective stance. Quantitative research focuses on numberic and unchanging data and detailed, convergent reasoning rather than divergent reasoning [i.e., the generation of a variety of ideas about a research problem in a spontaneous, free-flowing manner].

Its main characteristics are :

- The data is usually gathered using structured research instruments.

- The results are based on larger sample sizes that are representative of the population.

- The research study can usually be replicated or repeated, given its high reliability.

- Researcher has a clearly defined research question to which objective answers are sought.

- All aspects of the study are carefully designed before data is collected.

- Data are in the form of numbers and statistics, often arranged in tables, charts, figures, or other non-textual forms.

- Project can be used to generalize concepts more widely, predict future results, or investigate causal relationships.

- Researcher uses tools, such as questionnaires or computer software, to collect numerical data.

The overarching aim of a quantitative research study is to classify features, count them, and construct statistical models in an attempt to explain what is observed.

Things to keep in mind when reporting the results of a study using quantiative methods :

- Explain the data collected and their statistical treatment as well as all relevant results in relation to the research problem you are investigating. Interpretation of results is not appropriate in this section.

- Report unanticipated events that occurred during your data collection. Explain how the actual analysis differs from the planned analysis. Explain your handling of missing data and why any missing data does not undermine the validity of your analysis.

- Explain the techniques you used to "clean" your data set.

- Choose a minimally sufficient statistical procedure ; provide a rationale for its use and a reference for it. Specify any computer programs used.

- Describe the assumptions for each procedure and the steps you took to ensure that they were not violated.

- When using inferential statistics , provide the descriptive statistics, confidence intervals, and sample sizes for each variable as well as the value of the test statistic, its direction, the degrees of freedom, and the significance level [report the actual p value].

- Avoid inferring causality , particularly in nonrandomized designs or without further experimentation.

- Use tables to provide exact values ; use figures to convey global effects. Keep figures small in size; include graphic representations of confidence intervals whenever possible.

- Always tell the reader what to look for in tables and figures .

NOTE: When using pre-existing statistical data gathered and made available by anyone other than yourself [e.g., government agency], you still must report on the methods that were used to gather the data and describe any missing data that exists and, if there is any, provide a clear explanation why the missing datat does not undermine the validity of your final analysis.

Babbie, Earl R. The Practice of Social Research . 12th ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage, 2010; Brians, Craig Leonard et al. Empirical Political Analysis: Quantitative and Qualitative Research Methods . 8th ed. Boston, MA: Longman, 2011; McNabb, David E. Research Methods in Public Administration and Nonprofit Management: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches . 2nd ed. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2008; Quantitative Research Methods . Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Singh, Kultar. Quantitative Social Research Methods . Los Angeles, CA: Sage, 2007.

Basic Research Designs for Quantitative Studies

Before designing a quantitative research study, you must decide whether it will be descriptive or experimental because this will dictate how you gather, analyze, and interpret the results. A descriptive study is governed by the following rules: subjects are generally measured once; the intention is to only establish associations between variables; and, the study may include a sample population of hundreds or thousands of subjects to ensure that a valid estimate of a generalized relationship between variables has been obtained. An experimental design includes subjects measured before and after a particular treatment, the sample population may be very small and purposefully chosen, and it is intended to establish causality between variables. Introduction The introduction to a quantitative study is usually written in the present tense and from the third person point of view. It covers the following information:

- Identifies the research problem -- as with any academic study, you must state clearly and concisely the research problem being investigated.

- Reviews the literature -- review scholarship on the topic, synthesizing key themes and, if necessary, noting studies that have used similar methods of inquiry and analysis. Note where key gaps exist and how your study helps to fill these gaps or clarifies existing knowledge.

- Describes the theoretical framework -- provide an outline of the theory or hypothesis underpinning your study. If necessary, define unfamiliar or complex terms, concepts, or ideas and provide the appropriate background information to place the research problem in proper context [e.g., historical, cultural, economic, etc.].

Methodology The methods section of a quantitative study should describe how each objective of your study will be achieved. Be sure to provide enough detail to enable the reader can make an informed assessment of the methods being used to obtain results associated with the research problem. The methods section should be presented in the past tense.

- Study population and sampling -- where did the data come from; how robust is it; note where gaps exist or what was excluded. Note the procedures used for their selection;

- Data collection – describe the tools and methods used to collect information and identify the variables being measured; describe the methods used to obtain the data; and, note if the data was pre-existing [i.e., government data] or you gathered it yourself. If you gathered it yourself, describe what type of instrument you used and why. Note that no data set is perfect--describe any limitations in methods of gathering data.

- Data analysis -- describe the procedures for processing and analyzing the data. If appropriate, describe the specific instruments of analysis used to study each research objective, including mathematical techniques and the type of computer software used to manipulate the data.

Results The finding of your study should be written objectively and in a succinct and precise format. In quantitative studies, it is common to use graphs, tables, charts, and other non-textual elements to help the reader understand the data. Make sure that non-textual elements do not stand in isolation from the text but are being used to supplement the overall description of the results and to help clarify key points being made. Further information about how to effectively present data using charts and graphs can be found here .

- Statistical analysis -- how did you analyze the data? What were the key findings from the data? The findings should be present in a logical, sequential order. Describe but do not interpret these trends or negative results; save that for the discussion section. The results should be presented in the past tense.

Discussion Discussions should be analytic, logical, and comprehensive. The discussion should meld together your findings in relation to those identified in the literature review, and placed within the context of the theoretical framework underpinning the study. The discussion should be presented in the present tense.

- Interpretation of results -- reiterate the research problem being investigated and compare and contrast the findings with the research questions underlying the study. Did they affirm predicted outcomes or did the data refute it?

- Description of trends, comparison of groups, or relationships among variables -- describe any trends that emerged from your analysis and explain all unanticipated and statistical insignificant findings.

- Discussion of implications – what is the meaning of your results? Highlight key findings based on the overall results and note findings that you believe are important. How have the results helped fill gaps in understanding the research problem?

- Limitations -- describe any limitations or unavoidable bias in your study and, if necessary, note why these limitations did not inhibit effective interpretation of the results.

Conclusion End your study by to summarizing the topic and provide a final comment and assessment of the study.

- Summary of findings – synthesize the answers to your research questions. Do not report any statistical data here; just provide a narrative summary of the key findings and describe what was learned that you did not know before conducting the study.

- Recommendations – if appropriate to the aim of the assignment, tie key findings with policy recommendations or actions to be taken in practice.

- Future research – note the need for future research linked to your study’s limitations or to any remaining gaps in the literature that were not addressed in your study.

Black, Thomas R. Doing Quantitative Research in the Social Sciences: An Integrated Approach to Research Design, Measurement and Statistics . London: Sage, 1999; Gay,L. R. and Peter Airasain. Educational Research: Competencies for Analysis and Applications . 7th edition. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merril Prentice Hall, 2003; Hector, Anestine. An Overview of Quantitative Research in Compostion and TESOL . Department of English, Indiana University of Pennsylvania; Hopkins, Will G. “Quantitative Research Design.” Sportscience 4, 1 (2000); A Strategy for Writing Up Research Results . The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College; Nenty, H. Johnson. "Writing a Quantitative Research Thesis." International Journal of Educational Science 1 (2009): 19-32; Ouyang, Ronghua (John). Basic Inquiry of Quantitative Research . Kennesaw State University.

- << Previous: Finding Quantitative Research

- Next: Databases >>

- Last Updated: Jul 11, 2023 1:03 PM

- URL: https://libguides.iun.edu/S371socialworkresearch

Social Work Research Methods That Drive the Practice

Social workers advocate for the well-being of individuals, families and communities. But how do social workers know what interventions are needed to help an individual? How do they assess whether a treatment plan is working? What do social workers use to write evidence-based policy?

Social work involves research-informed practice and practice-informed research. At every level, social workers need to know objective facts about the populations they serve, the efficacy of their interventions and the likelihood that their policies will improve lives. A variety of social work research methods make that possible.

Data-Driven Work

Data is a collection of facts used for reference and analysis. In a field as broad as social work, data comes in many forms.

Quantitative vs. Qualitative

As with any research, social work research involves both quantitative and qualitative studies.

Quantitative Research

Answers to questions like these can help social workers know about the populations they serve — or hope to serve in the future.

- How many students currently receive reduced-price school lunches in the local school district?

- How many hours per week does a specific individual consume digital media?

- How frequently did community members access a specific medical service last year?

Quantitative data — facts that can be measured and expressed numerically — are crucial for social work.

Quantitative research has advantages for social scientists. Such research can be more generalizable to large populations, as it uses specific sampling methods and lends itself to large datasets. It can provide important descriptive statistics about a specific population. Furthermore, by operationalizing variables, it can help social workers easily compare similar datasets with one another.

Qualitative Research

Qualitative data — facts that cannot be measured or expressed in terms of mere numbers or counts — offer rich insights into individuals, groups and societies. It can be collected via interviews and observations.

- What attitudes do students have toward the reduced-price school lunch program?

- What strategies do individuals use to moderate their weekly digital media consumption?

- What factors made community members more or less likely to access a specific medical service last year?

Qualitative research can thereby provide a textured view of social contexts and systems that may not have been possible with quantitative methods. Plus, it may even suggest new lines of inquiry for social work research.

Mixed Methods Research

Combining quantitative and qualitative methods into a single study is known as mixed methods research. This form of research has gained popularity in the study of social sciences, according to a 2019 report in the academic journal Theory and Society. Since quantitative and qualitative methods answer different questions, merging them into a single study can balance the limitations of each and potentially produce more in-depth findings.

However, mixed methods research is not without its drawbacks. Combining research methods increases the complexity of a study and generally requires a higher level of expertise to collect, analyze and interpret the data. It also requires a greater level of effort, time and often money.

The Importance of Research Design

Data-driven practice plays an essential role in social work. Unlike philanthropists and altruistic volunteers, social workers are obligated to operate from a scientific knowledge base.

To know whether their programs are effective, social workers must conduct research to determine results, aggregate those results into comprehensible data, analyze and interpret their findings, and use evidence to justify next steps.

Employing the proper design ensures that any evidence obtained during research enables social workers to reliably answer their research questions.

Research Methods in Social Work

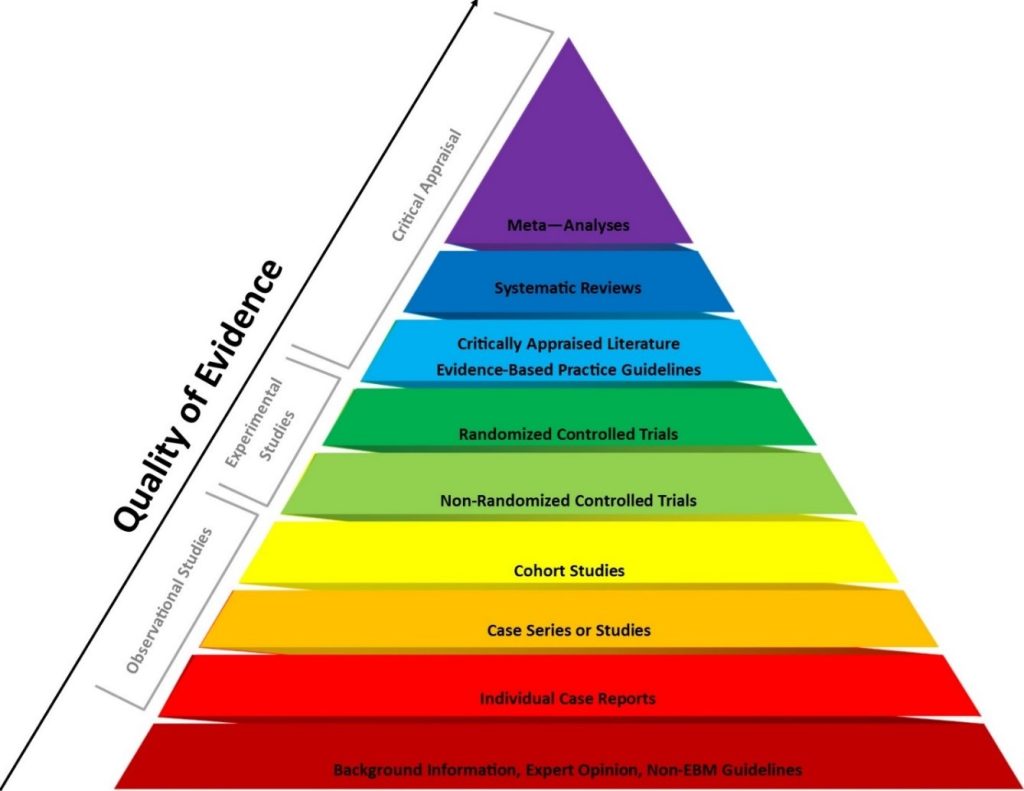

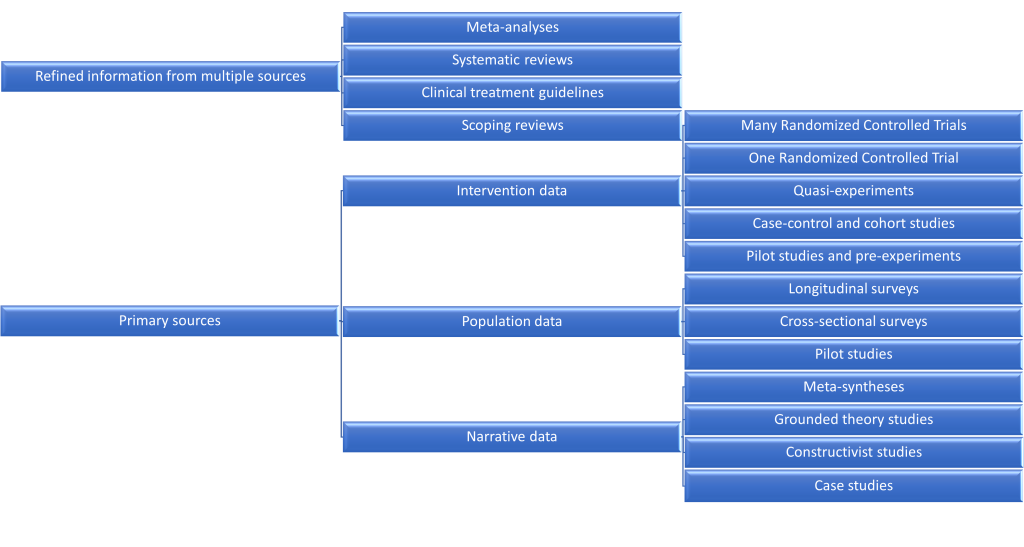

The various social work research methods have specific benefits and limitations determined by context. Common research methods include surveys, program evaluations, needs assessments, randomized controlled trials, descriptive studies and single-system designs.

Surveys involve a hypothesis and a series of questions in order to test that hypothesis. Social work researchers will send out a survey, receive responses, aggregate the results, analyze the data, and form conclusions based on trends.

Surveys are one of the most common research methods social workers use — and for good reason. They tend to be relatively simple and are usually affordable. However, surveys generally require large participant groups, and self-reports from survey respondents are not always reliable.

Program Evaluations

Social workers ally with all sorts of programs: after-school programs, government initiatives, nonprofit projects and private programs, for example.

Crucially, social workers must evaluate a program’s effectiveness in order to determine whether the program is meeting its goals and what improvements can be made to better serve the program’s target population.

Evidence-based programming helps everyone save money and time, and comparing programs with one another can help social workers make decisions about how to structure new initiatives. Evaluating programs becomes complicated, however, when programs have multiple goal metrics, some of which may be vague or difficult to assess (e.g., “we aim to promote the well-being of our community”).

Needs Assessments

Social workers use needs assessments to identify services and necessities that a population lacks access to.

Common social work populations that researchers may perform needs assessments on include:

- People in a specific income group

- Everyone in a specific geographic region

- A specific ethnic group

- People in a specific age group

In the field, a social worker may use a combination of methods (e.g., surveys and descriptive studies) to learn more about a specific population or program. Social workers look for gaps between the actual context and a population’s or individual’s “wants” or desires.

For example, a social worker could conduct a needs assessment with an individual with cancer trying to navigate the complex medical-industrial system. The social worker may ask the client questions about the number of hours they spend scheduling doctor’s appointments, commuting and managing their many medications. After learning more about the specific client needs, the social worker can identify opportunities for improvements in an updated care plan.

In policy and program development, social workers conduct needs assessments to determine where and how to effect change on a much larger scale. Integral to social work at all levels, needs assessments reveal crucial information about a population’s needs to researchers, policymakers and other stakeholders. Needs assessments may fall short, however, in revealing the root causes of those needs (e.g., structural racism).

Randomized Controlled Trials

Randomized controlled trials are studies in which a randomly selected group is subjected to a variable (e.g., a specific stimulus or treatment) and a control group is not. Social workers then measure and compare the results of the randomized group with the control group in order to glean insights about the effectiveness of a particular intervention or treatment.

Randomized controlled trials are easily reproducible and highly measurable. They’re useful when results are easily quantifiable. However, this method is less helpful when results are not easily quantifiable (i.e., when rich data such as narratives and on-the-ground observations are needed).

Descriptive Studies

Descriptive studies immerse the researcher in another context or culture to study specific participant practices or ways of living. Descriptive studies, including descriptive ethnographic studies, may overlap with and include other research methods:

- Informant interviews

- Census data

- Observation

By using descriptive studies, researchers may glean a richer, deeper understanding of a nuanced culture or group on-site. The main limitations of this research method are that it tends to be time-consuming and expensive.

Single-System Designs

Unlike most medical studies, which involve testing a drug or treatment on two groups — an experimental group that receives the drug/treatment and a control group that does not — single-system designs allow researchers to study just one group (e.g., an individual or family).

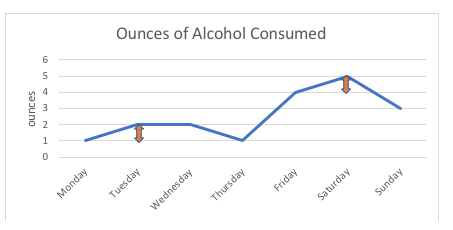

Single-system designs typically entail studying a single group over a long period of time and may involve assessing the group’s response to multiple variables.

For example, consider a study on how media consumption affects a person’s mood. One way to test a hypothesis that consuming media correlates with low mood would be to observe two groups: a control group (no media) and an experimental group (two hours of media per day). When employing a single-system design, however, researchers would observe a single participant as they watch two hours of media per day for one week and then four hours per day of media the next week.

These designs allow researchers to test multiple variables over a longer period of time. However, similar to descriptive studies, single-system designs can be fairly time-consuming and costly.

Learn More About Social Work Research Methods

Social workers have the opportunity to improve the social environment by advocating for the vulnerable — including children, older adults and people with disabilities — and facilitating and developing resources and programs.

Learn more about how you can earn your Master of Social Work online at Virginia Commonwealth University . The highest-ranking school of social work in Virginia, VCU has a wide range of courses online. That means students can earn their degrees with the flexibility of learning at home. Learn more about how you can take your career in social work further with VCU.

From M.S.W. to LCSW: Understanding Your Career Path as a Social Worker

How Palliative Care Social Workers Support Patients With Terminal Illnesses

How to Become a Social Worker in Health Care

Gov.uk, Mixed Methods Study

MVS Open Press, Foundations of Social Work Research

Open Social Work Education, Scientific Inquiry in Social Work

Open Social Work, Graduate Research Methods in Social Work: A Project-Based Approach

Routledge, Research for Social Workers: An Introduction to Methods

SAGE Publications, Research Methods for Social Work: A Problem-Based Approach

Theory and Society, Mixed Methods Research: What It Is and What It Could Be

READY TO GET STARTED WITH OUR ONLINE M.S.W. PROGRAM FORMAT?

Bachelor’s degree is required.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

19 11. Quantitative measurement

Chapter outline.

- Overview of measurement (11 minute read)

- Operationalization and levels of measurement (20 minute read)

- Scales and indices (15 minute read)

- Reliability and validity (20 minute read)

- Ethical and social justice considerations for measurement (6 minute read)

Content warning: Discussions of immigration issues, parents and gender identity, anxiety, and substance use.

11.1 Overview of measurement

Learning Objectives

Learners will be able to…

- Provide an overview of the measurement process in social work research

- Describe why accurate measurement is important for research

This chapter begins with an interesting question: Is my apple the same as your apple? Let’s pretend you want to study apples. Perhaps you have read that chemicals in apples may impact neurotransmitters and you want to test if apple consumption improves mood among college students. So, in order to conduct this study, you need to make sure that you provide apples to a treatment group, right? In order to increase the rigor of your study, you may also want to have a group of students, ones who do not get to eat apples, to serve as a comparison group. Don’t worry if this seems new to you. We will discuss this type of design in Chapter 13 . For now, just concentrate on apples.

In order to test your hypothesis about apples, you need to define exactly what is meant by the term “apple” so you ensure everyone is consuming the same thing. You also need to know what you consider a “dose” of this thing that we call “apple” and make sure everyone is consuming the same kind of apples and you need a way to ensure that you give the same amount of apples to everyone in your treatment group. So, let’s start by making sure we understand what the term “apple” means. Say you have an object that you identify as an apple and I have an object that I identify as an apple. Perhaps my “apple” is a chocolate apple, one that looks similar to an apple but made of chocolate and red dye, and yours is a honeycrisp. Perhaps yours is papier-mache and mine is a Macbook Pro. All of these are defined as apples, right?

You can see the multitude of ways we could conceptualize “apple,” and how that could create a problem for our research. If I get a Red Delicious (ick) apple and you get a Granny Smith (yum) apple and we observe a change in neurotransmitters, it’s going to be even harder than usual to say the apple influenced the neurotransmitters because we didn’t define “apple” well enough. Measurement in this case is essential to treatment fidelity , which is when you ensure that everyone receives the same, or close to the same, treatment as possible. In other words, you need to make sure everyone is consuming the same kind of apples and you need a way to ensure that you give the same amount of apples to everyone in your treatment group.

In social science, when we use the term measurement , we mean the process by which we describe and ascribe meaning to the key facts, concepts, or other phenomena that we are investigating. At its core, measurement is about defining one’s terms in as clear and precise a way as possible. Of course, measurement in social science isn’t quite as simple as using a measuring cup or spoon, but there are some basic tenets on which most social scientists agree when it comes to measurement. We’ll explore those, as well as some of the ways that measurement might vary depending on your unique approach to the study of your topic.

An important point here is that measurement does not require any particular instruments or procedures. What it does require is some systematic procedure for assigning scores, meanings, and descriptions to individuals or objects so that those scores represent the characteristic of interest. You can measure phenomena in many different ways, but you must be sure that how you choose to measure gives you information and data that lets you answer your research question. If you’re looking for information about a person’s income, but your main points of measurement have to do with the money they have in the bank, you’re not really going to find the information you’re looking for!

What do social scientists measure?

The question of what social scientists measure can be answered by asking yourself what social scientists study. Think about the topics you’ve learned about in other social work classes you’ve taken or the topics you’ve considered investigating yourself. Let’s consider Melissa Milkie and Catharine Warner’s study (2011) [1] of first graders’ mental health. In order to conduct that study, Milkie and Warner needed to have some idea about how they were going to measure mental health. What does mental health mean, exactly? And how do we know when we’re observing someone whose mental health is good and when we see someone whose mental health is compromised? Understanding how measurement works in research methods helps us answer these sorts of questions.

As you might have guessed, social scientists will measure just about anything that they have an interest in investigating. For example, those who are interested in learning something about the correlation between social class and levels of happiness must develop some way to measure both social class and happiness. Those who wish to understand how well immigrants cope in their new locations must measure immigrant status and coping. Those who wish to understand how a person’s gender shapes their workplace experiences must measure gender and workplace experiences. You get the idea. Social scientists can and do measure just about anything you can imagine observing or wanting to study. Of course, some things are easier to observe or measure than others.

In 1964, philosopher Abraham Kaplan (1964) [2] wrote The Conduct of Inquiry, which has since become a classic work in research methodology (Babbie, 2010). [3] In his text, Kaplan describes different categories of things that behavioral scientists observe. One of those categories, which Kaplan called “observational terms,” is probably the simplest to measure in social science. Observational terms are the sorts of things that we can see with the naked eye simply by looking at them. Kaplan roughly defines them as conditions that are easy to identify and verify through direct observation. If, for example, we wanted to know how the conditions of playgrounds differ across different neighborhoods, we could directly observe the variety, amount, and condition of equipment at various playgrounds.

Indirect observables , on the other hand, are less straightforward to assess. In Kaplan’s framework, they are conditions that are subtle and complex that we must use existing knowledge and intuition to define.If we conducted a study for which we wished to know a person’s income, we’d probably have to ask them their income, perhaps in an interview or a survey. Thus, we have observed income, even if it has only been observed indirectly. Birthplace might be another indirect observable. We can ask study participants where they were born, but chances are good we won’t have directly observed any of those people being born in the locations they report.

How do social scientists measure?

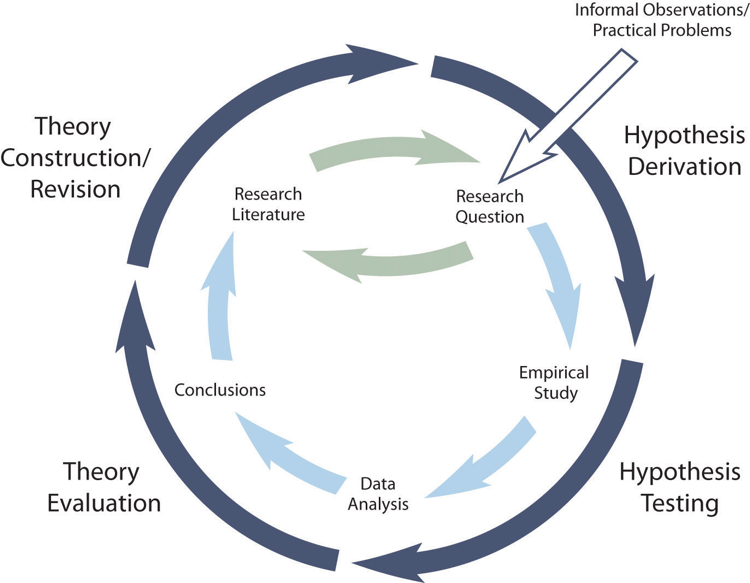

Measurement in social science is a process. It occurs at multiple stages of a research project: in the planning stages, in the data collection stage, and sometimes even in the analysis stage. Recall that previously we defined measurement as the process by which we describe and ascribe meaning to the key facts, concepts, or other phenomena that we are investigating. Once we’ve identified a research question, we begin to think about what some of the key ideas are that we hope to learn from our project. In describing those key ideas, we begin the measurement process.

Let’s say that our research question is the following: How do new college students cope with the adjustment to college? In order to answer this question, we’ll need some idea about what coping means. We may come up with an idea about what coping means early in the research process, as we begin to think about what to look for (or observe) in our data-collection phase. Once we’ve collected data on coping, we also have to decide how to report on the topic. Perhaps, for example, there are different types or dimensions of coping, some of which lead to more successful adjustment than others. However we decide to proceed, and whatever we decide to report, the point is that measurement is important at each of these phases.

As the preceding example demonstrates, measurement is a process in part because it occurs at multiple stages of conducting research. We could also think of measurement as a process because it involves multiple stages. From identifying your key terms to defining them to figuring out how to observe them and how to know if your observations are any good, there are multiple steps involved in the measurement process. An additional step in the measurement process involves deciding what elements your measures contain. A measure’s elements might be very straightforward and clear, particularly if they are directly observable. Other measures are more complex and might require the researcher to account for different themes or types. These sorts of complexities require paying careful attention to a concept’s level of measurement and its dimensions. We’ll explore these complexities in greater depth at the end of this chapter, but first let’s look more closely at the early steps involved in the measurement process, starting with conceptualization.

The idea of coming up with your own measurement tool might sound pretty intimidating at this point. The good news is that if you find something in the literature that works for you, you can use it with proper attribution. If there are only pieces of it that you like, you can just use those pieces, again with proper attribution. You don’t always have to start from scratch!

Key Takeaways

- Measurement (i.e. the measurement process) gives us the language to define/describe what we are studying.

- In research, when we develop measurement tools, we move beyond concepts that may be subjective and abstract to a definition that is clear and concise.

- Good social work researchers are intentional with the measurement process.

- Engaging in the measurement process requires us to think critically about what we want to study. This process may be challenging and potentially time-consuming.

- How easy or difficult do you believe it will be to study these topics?

- Think about the chapter on literature reviews. Is there a significant body of literature on the topics you are interested in studying?

- Are there existing measurement tools that may be appropriate to use for the topics you are interested in studying?

11.2 Operationalization and levels of measurement

- Define constructs and operationalization and describe their relationship

- Be able to start operationalizing variables in your research project

- Identify the level of measurement for each type of variable

- Demonstrate knowledge of how each type of variable can be used

Now we have some ideas about what and how social scientists need to measure, so let’s get into the details. In this section, we are going to talk about how to make your variables measurable (operationalization) and how you ultimately characterize your variables in order to analyze them (levels of measurement).

Operationalizing your variables

“Operationalizing” is not a word I’d ever heard before I became a researcher, and actually, my browser’s spell check doesn’t even recognize it. I promise it’s a real thing, though. In the most basic sense, when we operationalize a variable, we break it down into measurable parts. Operationalization is the process of determining how to measure a construct that cannot be directly observed. And a constructs are conditions that are not directly observable and represent states of being, experiences, and ideas. But why construct ? We call them constructs because they are built using different ideas and parameters.

As we know from Section 11.1, sometimes the measures that we are interested in are more complex and more abstract than observational terms or indirect observables . Think about some of the things you’ve learned about in other social work classes—for example, ethnocentrism. What is ethnocentrism? Well, from completing an introduction to social work class you might know that it’s a construct that has something to do with the way a person judges another’s culture. But how would you measure it? Here’s another construct: bureaucracy. We know this term has something to do with organizations and how they operate, but measuring such a construct is trickier than measuring, say, a person’s income. In both cases, ethnocentrism and bureaucracy, these theoretical notions represent ideas whose meaning we have come to agree on. Though we may not be able to observe these abstractions directly, we can observe the things that they are made up of.

Now, let’s operationalize bureaucracy and ethnocentrism. The construct of bureaucracy could be measured by counting the number of supervisors that need to approve routine spending by public administrators. The greater the number of administrators that must sign off on routine matters, the greater the degree of bureaucracy. Similarly, we might be able to ask a person the degree to which they trust people from different cultures around the world and then assess the ethnocentrism inherent in their answers. We can measure constructs like bureaucracy and ethnocentrism by defining them in terms of what we can observe.

How we operationalize our constructs (and ultimately measure our variables) can affect the conclusions we can draw from our research. Let’s say you’re reviewing a state program to make it more efficient in connecting people to public services. What might be different if we decide to measure bureaucracy by the number of forms someone has to fill out to get a public service instead of the number of people who have to review the forms, like we talked about above? Maybe you find that there is an unnecessary amount of paperwork based on comparisons to other state programs, so you recommend that some of it be eliminated. This is probably a good thing, but will it actually make the program more efficient like eliminating some of the reviews that paperwork has to go through would? I’m not really making a judgment on which way is better to measure bureaucracy, but I encourage you to think about the costs and benefits of each way we operationalized the construct of bureaucracy, and extend this to the way you operationalize your own concepts in your research project.

Levels of Measurement

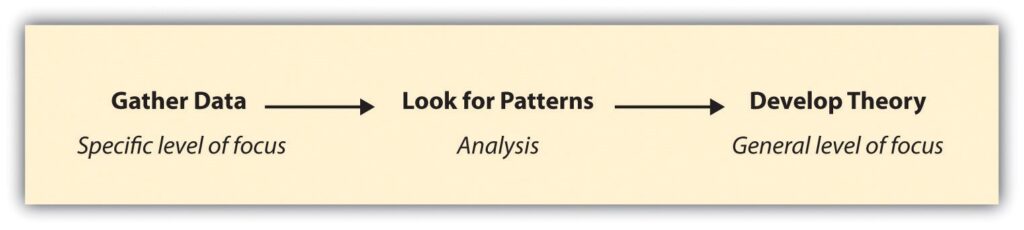

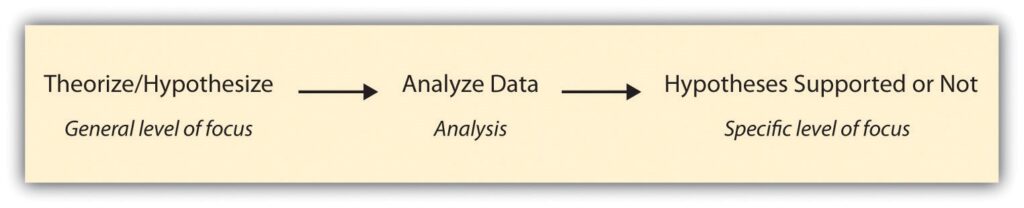

Now, we’re going to move into some more concrete characterizations of variables. You now hopefully understand how to operationalize your concepts so that you can turn them into variables. Imagine a process kind of like what you see in Figure 11.1 below.

Notice that the arrows from the construct point toward the research question, because ultimately, measuring them will help answer your question!

The level of measuremen t of a variable tells us how the values of the variable relate to each other and what mathematical operations we can perform with the variable. (That second part will become important once we move into quantitative analysis in Chapter 14 and Chapter 15 ). Many students find this definition a bit confusing. What does it mean when we say that the level of measurement tells us about mathematical operations? So before we move on, let’s clarify this a bit.

Let’s say you work for your a community nonprofit that wants to develop programs relevant to community members’ ages (i.e., tutoring for kids in school, job search and resume help for adults, and home visiting for elderly community members). However, you do not have a good understanding of the ages of the people who visit your community center. Below is a part of a questionnaire that you developed to.

- How old are you? – Under 18 years old – 18-30 years old – 31-50 years old – 51-60 years old – Over 60 years old

- How old are you? _____ years

Look at the two items on this questionnaire. They both ask about age, but t he first item asks about age but asks the participant to identify the age range. The second item asks you to identify the actual age in years. These two questions give us data that represent the same information measured at a different level.

It would help your agency if you knew the average age of clients, right? So, which item on the questionnaire will provide this information? Item one’s choices are grouped into categories. Can you compute an average age from these choices? No. Conversely, participants completing item two are asked to provide an actual number, one that you could use to determine an average age. In summary, the two items both ask the participants to report their age. However, the type of data collected from both items is different and must be analyzed differently.

We can think about the four levels of measurement as going from less to more specific, or as it’s more commonly called, lower to higher: nominal, ordinal , interval , and ratio . Each of these levels differ and help the researcher understand something about their data. Think about levels of measurement as a hierarchy.

In order to determine the level of measurement, please examine your data and then ask these four questions (in order).

- Do I have mutually exclusive categories? If the answer is yes, continue to question #2.

- Do my item choices have a hierarchy or order? In other words, can you put your item choices in order? If no, stop–you have nominal level data. If the answer is yes, continue to question #3.

- Can I add, subtract, divide, and multiply my answer choices? If no, stop–you have ordinal level data. If the answer is yes, continue to question #4.

- Is it possible that the answer to this item can be zero? If the answer is no—you have interval level data. If the answer is yes, you are at the ratio level of measurement.

Nominal level . The nominal level of measurement is the lowest level of measurement. It contains categories are mutually exclusive, which means means that anyone who falls into one category cannot not fall into another category. The data can be represented with words (like yes/no) or numbers that correspond to words or a category (like 1 equaling yes and 0 equaling no). Even when the categories are represented as numbers in our data, the number itself does not have an actual numerical value. It is merely a number we have assigned so that we can use the variable in mathematical operations (which we will start talking about in Chapter 14.1 ). We say this level of measurement is lowest or least specific because someone who falls into a category we’ve designated could differ from someone else in the same category. Let’s say on our questionnaire above, we also asked folks whether they own a car. They can answer yes or no, and they fall into mutually exclusive categories. In this case, we would know whether they own a car, but not whether owning a car really affects their life significantly. Maybe they have chosen not to own one and are happy to take the bus, bike, or walk. Maybe they do not own one but would like to own one. We cannot get this information from a nominal variable, which is ok when we have meaningful categories. Nominal variables are especially useful when we just need the frequency of a particular characteristic in our sample.

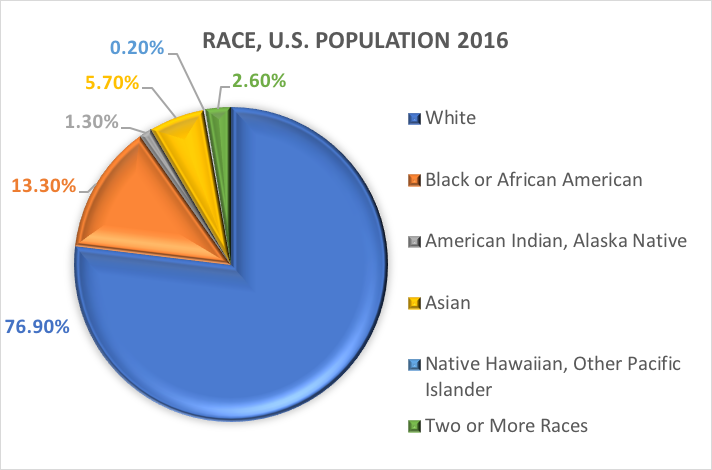

The nominal level of measurement usually includes many demographic characteristics like race, gender, or marital status.

Ordinal leve l . The ordinal level of measurement is the next level of measurement and contains slightly more specific information than the nominal level. This level has mutually exclusive categories and a hierarchy or order. Let’s go back to the first item on the questionnaire we talked about above.

Do we have mutually exclusive categories? Yes. Someone who selects item A cannot also select item B. So, we know that we have at least nominal level data. However, the next question that we need to ask is “Do my answer choices have order?” or “Can I put my answer choices in order?” The answer is yes, someone who selects A is younger than someone who selects B or C. So, you have at least ordinal level data.

From a data analysis and statistical perspective, ordinal variables get treated exactly like nominal variables because they are both categorical variables , or variables whose values are organized into mutually exclusive groups but whose numerical values cannot be used in mathematical operations. You’ll see this term used again when we get into bivariate analysis in Chapter 15.

Interval level The interval level of measurement is a higher level of measurement. This level marks the point where we are able . This level contains all of the characteristics of the previous levels (mutually exclusive categories and order). What distinguishes it from the ordinal level is that the interval level can be used to conduct mathematical computations with data (like an average, for instance).

Let’s think back to our questionnaire about age again and take a look at the second question where we asked for a person’s exact age in years. Age in years is mutually exclusive – someone can’t be 14 and 15 at the same time – and the order of ages is meaningful, since being 18 means something different than being 32. Now, we can also take the answers to this question and do math with them, like addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division.

Ratio level . Ratio level data is the highest level of measurement. It has mutually exclusive categories, order, and you can perform mathematical operations on it. The main difference between the interval and ratio levels is that the ratio level has an absolute zero, meaning that a value of zero is both possible and meaningful. You might be thinking, “Well, age has an absolute zero,” but someone who is not yet born does not have an age, and the minute they’re born, they are not zero years old anymore.

Data at the ratio level of measurement are usually amounts or numbers of things, and can be negative (if that makes conceptual sense, of course). For example, you could ask someone to report how many A’s they have on their transcript or how many semesters they have earned a 4.0. They could have zero A’s and that would be a valid answer.

From a data analysis and statistical perspective, interval and ratio variables are treated exactly the same because they are both continuous variables , or variables whose values are mutually exclusive and can be used in mathematical operations. Technically, a continuous variable could have an infinite number of values.

What does the level of measurement tell us?

We have spent time learning how to determine our data’s level of measurement. Now what? How could we use this information to help us as we measure concepts and develop measurement tools? First, the types of statistical tests that we are able to use are dependent on our data’s level of measurement. (We will discuss this soon in Chapter 15.) The higher the level of measurement, the more complex statistical tests we are able to conduct. This knowledge may help us decide what kind of data we need to gather, and how. That said, we have to balance this knowledge with the understanding that sometimes, collecting data at a higher level of measurement could negatively impact our studies. For instance, sometimes providing answers in ranges may make prospective participants feel more comfortable responding to sensitive items. Imagine that you were interested in collecting information on topics such as income, number of sexual partners, number of times used illicit drugs, etc. You would have to think about the sensitivity of these items and determine if it would make more sense to collect some data at a lower level of measurement.

Finally, sometimes when analyzing data, researchers find a need to change a data’s level of measurement. For example, a few years ago, a student was interested in studying the relationship between mental health and life satisfaction. This student collected a variety of data. One item asked about the number of mental health diagnoses, reported as the actual number. When analyzing data, my student examined the mental health diagnosis variable and noticed that she had two groups, those with none or one diagnosis and those with many diagnoses. Instead of using the ratio level data (actual number of mental health diagnoses), she collapsed her cases into two categories, few and many. She decided to use this variable in her analyses. It is important to note that you can move a higher level of data to a lower level of data; however, you are unable to move a lower level to a higher level.

- Operationalization involves figuring out how to measure a construct you cannot directly observe.

- Nominal variables have mutually exclusive categories with no natural order. They cannot be used for mathematical operations like addition or subtraction. Race or gender would be one example.

- Ordinal variables have mutually exclusive categories and a natural order. They also cannot be used for mathematical operations like addition or subtraction. Age when measured in categories (i.e., 18-25 years old) would be an example.

- Interval variables have mutually exclusive categories, a natural order, and can be used for mathematical operations. Age as a raw number would be an example.

- Ratio variables have mutually exclusive categories, a natural order, can be used for mathematical operations, and have an absolute zero value. The number of times someone calls a legislator to advocate for a policy would be an example.

- Nominal and ordinal variables are categorical variables, meaning they have mutually exclusive categories and cannot be used for mathematical operations, even when assigned a number.

- Interval and ratio variables are continuous variables, meaning their values are mutually exclusive and can be used in mathematical operations.

- Researchers should consider the costs and benefits of how they operationalize their variables, including what level of measurement they choose, since the level of measurement can affect how you must gather your data.

- What are the primary constructs being explored in the research?

- Could you (or the study authors) have chosen another way to operationalize this construct?

- What are these variables’ levels of measurement?

- Are they categorical or continuous?

11.3 Scales and indices

- Identify different types of scales and compare them to each other

- Understand how to begin the process of constructing scales or indices

Quantitative data analysis requires the construction of two types of measures of variables: indices and scales. These measures are frequently used and are important since social scientists often study variables that possess no clear and unambiguous indicators–for instance, age or gender. Researchers often centralize much of work in regards to the attitudes and orientations of a group of people, which require several items to provide indication of the variables. Secondly, researchers seek to establish ordinal categories from very low to very high (vice-versa), which single data items can not ensure, while an index or scale can.

Although they exhibit differences (which will later be discussed) the two have in common various factors.

- Both are ordinal measures of variables.

- Both can order the units of analysis in terms of specific variables.

- Both are composite measures of variables ( measurements based on more than one one data item ).

In general, indices are a sum of series of individual yes/no questions, that are then combined in a single numeric score. They are usually a measure of the quantity of some social phenomenon and are constructed at a ratio level of measurement. More sophisticated indices weigh individual items according to their importance in the concept being measured (i.e. in a multiple choice test where different questions are worth different numbers of points). Some interval-level indices are not weight counted, but contain other indexes or scales within them (i.e. college admissions that score an applicant based on GPA, SAT scores, essays, and place a different point from each source).

This section discusses two formats used for measurement in research: scales and indices (sometimes called indexes). These two formats are helpful in research because they use multiple indicators to develop a composite (or total) score. Co mposite scores provide a much greater understanding of concepts than a single item could. Although we won’t delve too deeply into the process of scale development, we will cover some important topics for you to understand how scales and indices can be used.

Types of scales

As a student, you are very familiar with end of the semester course evaluations. These evaluations usually include statements such as, “My instructor created an environment of respect” and ask students to use a scale to indicate how much they agree or disagree with the statements. These scales, if developed and administered appropriately, provide a wealth of information to instructors that may be used to refine and update courses. If you examine the end of semester evaluations, you will notice that they are organized, use language that is specific to your course, and have very intentional methods of implementation. In essence, these tools are developed to encourage completion.

As you read about these scales, think about the information that you want to gather from participants. What type or types of scales would be the best for you to use and why? Are there existing scales or do you have to create your own?

The Likert scale

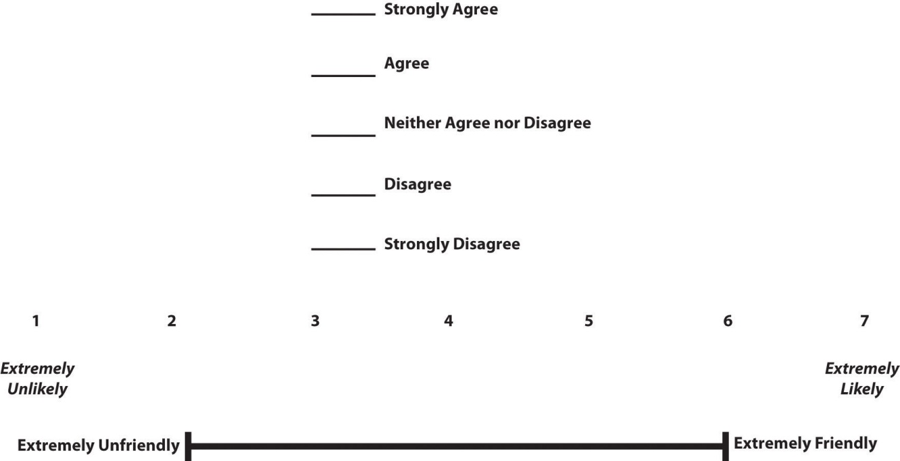

Most people have seen some version of a Likert scale. Designed by Rensis Likert (Likert, 1932) [4] , a Likert scale is a very popular rating scale for measuring ordinal data in social work research. This scale includes Likert items that are simply-worded statements to which participants can indicate their extent of agreement or disagreement on a five- or seven-point scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” You will also see Likert scales used for importance, quality, frequency, and likelihood, among lots of other concepts. Below is an example of how we might use a Likert scale to assess your attitudes about research as you work your way through this textbook.

Likert scales are excellent ways to collect information. They are popular; thus, your prospective participants may already be familiar with them. However, they do pose some challenges. You have to be very clear about your question prompts. What does strongly agree mean and how is this differentiated from agree ? In order to clarify this for participants, some researchers will place definitions of these items at the beginning of the tool.

There are a few other, less commonly used, scales discussed next.

Semantic differential scale

This is a composite (multi-item) scale where respondents are asked to indicate their opinions or feelings toward a single statement using different pairs of adjectives framed as polar opposites. For instance, in the above Likert scale, the participant is asked how much they agree or disagree with a statement. In a semantic differential scale, the participant is asked to indicate how they feel about a specific item. This makes the s emantic differential scale an excellent technique for measuring people’s attitudes or feelings toward objects, events, or behaviors. The following is an example of a semantic differential scale that was created to assess participants’ feelings about the content taught in their research class.

Feelings About My Research Class

Directions: Please review the pair of words and then select the one that most accurately reflects your feelings about the content of your research class.

Boring……………………………………….Exciting

Waste of Time…………………………..Worthwhile

Dry…………………………………………….Engaging

Irrelevant…………………………………..Relevant

Guttman scale

This composite scale was designed by Louis Guttman and uses a series of items arranged in increasing order of intensity (least intense to most intense) of the concept. This type of scale allows us to understand the intensity of beliefs or feelings. Each item in the above Guttman scale has a weight (this is not indicated on the tool) which varies with the intensity of that item, and the weighted combination of each response is used as an aggregate measure of an observation. Let’s pretend that you are working with a group of parents whose children have identified as part of the transgender community. You want to know how comfortable they feel with their children. You could develop the following items.

Example Guttman Scale Items

- I would allow my child to use a name that was not gender-specific (e.g., Ryan, Taylor) Yes/No

- I would allow my child to wear clothing of the opposite gender (e.g., dresses for boys) Yes/No

- I would allow my child to use the pronoun of the opposite sex Yes/No

- I would allow my child to live as the opposite gender Yes/No

Notice how the items move from lower intensity to higher intensity. A researcher reviews the yes answers and creates a score for each participant.

Indices (Indexes)

An index is a composite score derived from aggregating measures of multiple concepts (called components) using a set of rules and formulas. It is different from a scale. Scales also aggregate measures; however, these measures examine different dimensions or the same dimension of a single construct. A well-known example of an index is the consumer price index (CPI), which is computed every month by the Bureau of Labor Statistics of the U.S. Department of Labor. The CPI is a measure of how much consumers have to pay for goods and services (in general) and is divided into eight major categories (food and beverages, housing, apparel, transportation, healthcare, recreation, education and communication, and “other goods and services”), which are further subdivided into more than 200 smaller items. Each month, government employees call all over the country to get the current prices of more than 80,000 items. Using a complicated weighting scheme that takes into account the location and probability of purchase for each item, analysts then combine these prices into an overall index score using a series of formulas and rules.

Another example of an index is the Duncan Socioeconomic Index (SEI). This index is used to quantify a person’s socioeconomic status (SES) and is a combination of three concepts: income, education, and occupation. Income is measured in dollars, education in years or degrees achieved, and occupation is classified into categories or levels by status. These very different measures are combined to create an overall SES index score. However, SES index measurement has generated a lot of controversy and disagreement among researchers.

The process of creating an index is similar to that of a scale. First, conceptualize (define) the index and its constituent components. Though this appears simple, there may be a lot of disagreement on what components (concepts/constructs) should be included or excluded from an index. For instance, in the SES index, isn’t income correlated with education and occupation? And if so, should we include one component only or all three components? Reviewing the literature, using theories, and/or interviewing experts or key stakeholders may help resolve this issue. Second, operationalize and measure each component. For instance, how will you categorize occupations, particularly since some occupations may have changed with time (e.g., there were no Web developers before the Internet)? Third, create a rule or formula for calculating the index score. Again, this process may involve a lot of subjectivity. Lastly, validate the index score using existing or new data.

Differences Between Scales and Indices

Though indices and scales yield a single numerical score or value representing a concept of interest, they are different in many ways. First, indices often comprise components that are very different from each other (e.g., income, education, and occupation in the SES index) and are measured in different ways. Conversely, scales typically involve a set of similar items that use the same rating scale (such as a five-point Likert scale about customer satisfaction).

Second, indices often combine objectively measurable values such as prices or income, while scales are designed to assess subjective or judgmental constructs such as attitude, prejudice, or self-esteem. Some argue that the sophistication of the scaling methodology makes scales different from indexes, while others suggest that indexing methodology can be equally sophisticated. Nevertheless, indexes and scales are both essential tools in social science research.

A note on scales and indices

Scales and indices seem like clean, convenient ways to measure different phenomena in social science, but just like with a lot of research, we have to be mindful of the assumptions and biases underneath. What if a scale or an index was developed using only White women as research participants? Is it going to be useful for other groups? It very well might be, but when using a scale or index on a group for whom it hasn’t been tested, it will be very important to evaluate the validity and reliability of the instrument, which we address in the next section.

It’s important to note that while scales and indices are often made up of nominal or ordinal variables, when we analyze them into composite scores, we will treat them as interval/ratio variables.

- Scales and indices are common ways to collect information and involve using multiple indicators in measurement.

- A key difference between a scale and an index is that a scale contains multiple indicators for one concept, whereas an indicator examines multiple concepts (components).

- In order to create scales or indices, researchers must have a clear understanding of the indicators for what they are studying.

- What is the level of measurement for each item on each tool? Take a second and think about why the tool’s creator decided to include these levels of measurement. Identify any levels of measurement you would change and why.

- If these tools don’t exist for what you are interested in studying, why do you think that is?

11.4 Reliability and validity in measurement

- Discuss measurement error, the different types, and how to minimize the probability of them

- Differentiate between reliability and validity and understand how these are related to each other and relevant to understanding the value of a measurement tool

- Compare and contrast the types of reliability and demonstrate how to evaluate each type

- Compare and contrast the types of validity and demonstrate how to evaluate each type

The previous chapter provided insight into measuring concepts in social work research. We discussed the importance of identifying concepts and their corresponding indicators as a way to help us operationalize them. In essence, we now understand that when we think about our measurement process, we must be intentional and thoughtful in the choices that we make. Before we talk about how to evaluate our measurement process, let’s discuss why we want to evaluate our process. We evaluate our process so that we minimize our chances of error . But what is measurement error?

Types of Errors

We need to be concerned with two types of errors in measurement: systematic and random errors. Systematic errors are errors that are generally predictable. These are errors that, “are due to the process that biases the results.” [5] For instance, my cat stepping on the scale with me each morning is a systematic error in measuring my weight. I could predict that each measurement would be off by 13 pounds. (He’s a bit of a chonk.)

There are multiple categories of systematic errors.

- Social desirability , occurs when you ask participants a question and they answer in the way that they feel is the most socially desired . For instance, let's imagine that you want to understand the level of prejudice that participants feel regarding immigrants and decide to conduct face-to-face interviews with participants. Some participants may feel compelled to answer in a way that indicates that they are less prejudiced than they really are.

- [pb_glossary id="2096"]Acquiescence bias occurs when participants answer items in some type of pattern, usually skewed to more favorable responses. For example, imagine that you took a research class and loved it. The professor was great and you learned so much. When asked to complete the end of course questionnaire, you immediately mark "strongly agree" to all items without really reading all of the items. After all, you really loved the class. However, instead of reading and reflecting on each item, you "acquiesced" and used your overall impression of the experience to answer all of the items.

- Leading questions are those questions that are worded in a way so that the participant is "lead" to a specific answer. For instance, think about the question, "Have you ever hurt a sweet, innocent child?" Most people, regardless of their true response, may answer "no" simply because the wording of the question leads the participant to believe that "no" is the correct answer.

In order to minimize these types of errors, you should think about what you are studying and examine potential public perceptions of this issue. Next, think about how your questions are worded and how you will administer your tool (we will discuss these in greater detail in the next chapter). This will help you determine if your methods inadvertently increase the probability of these types of errors.

These errors differ from random errors , whic are "due to chance and are not systematic in any way." [6] Sometimes it is difficult to "tease out" random errors. When you take your statistics class, you will learn more about random errors and what to do about them. They're hard to observe until you start diving deeper into statistical analysis, so put a pin in them for now.

Now that we have a good understanding of the two types of errors, let's discuss what we can do to evaluate our measurement process and minimize the chances of these occurring. Remember, quality projects are clear on what is measured , how it is measured, and why it is measured . In addition, quality projects are attentive to the appropriateness of measurement tools and evaluate whether tools are used correctly and consistently. But how do we do that? Good researchers do not simply assume that their measures work. Instead, they collect data to demonstrate that they work. If their research does not demonstrate that a measure works, they stop using it. There are two key factors to consider in deciding whether your measurements are good: reliability and validity.

Reliability

Reliability refers to the consistency of a measure. Psychologists consider three types of reliability: over time (test-retest reliability), across items (internal consistency), and across different researchers (inter-rater reliability).

Test-retest reliability

When researchers measure a construct that they assume to be consistent across time, then the scores they obtain should also be consistent across time. Test-retest reliability is the extent to which this is actually the case. For example, intelligence is generally thought to be consistent across time. A person who is highly intelligent today will be highly intelligent next week. This means that any good measure of intelligence should produce roughly the same scores for this individual next week as it does today. Clearly, a measure that produces highly inconsistent scores over time cannot be a very good measure of a construct that is supposed to be consistent.

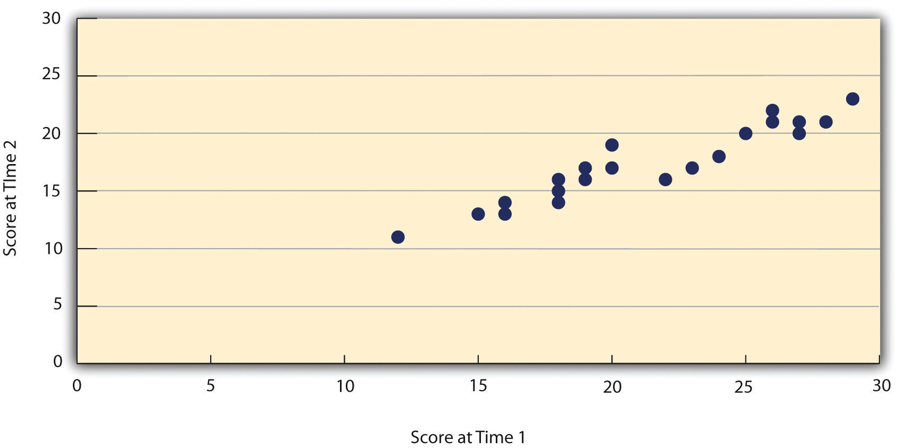

Assessing test-retest reliability requires using the measure on a group of people at one time, using it again on the same group of people at a later time. At neither point has the research participant received any sort of intervention. Once you have these two measurements, you then look at the correlation between the two sets of scores. This is typically done by graphing the data in a scatterplot and computing the correlation coefficient. Figure 11.2 shows the correlation between two sets of scores of several university students on the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, administered two times, a week apart. The correlation coefficient for these data is +.95. In general, a test-retest correlation of +.80 or greater is considered to indicate good reliability.

Again, high test-retest correlations make sense when the construct being measured is assumed to be consistent over time, which is the case for intelligence, self-esteem, and the Big Five personality dimensions. But other constructs are not assumed to be stable over time. The very nature of mood, for example, is that it changes. So a measure of mood that produced a low test-retest correlation over a period of a month would not be a cause for concern.

Internal consistency

Another kind of reliability is internal consistency , which is the consistency of people’s responses across the items on a multiple-item measure. In general, all the items on such measures are supposed to reflect the same underlying construct, so people’s scores on those items should be correlated with each other. On the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, people who agree that they are a person of worth should tend to agree that they have a number of good qualities. If people’s responses to the different items are not correlated with each other, then it would no longer make sense to claim that they are all measuring the same underlying construct. This is as true for behavioral and physiological measures as for self-report measures. For example, people might make a series of bets in a simulated game of roulette as a measure of their level of risk seeking. This measure would be internally consistent to the extent that individual participants’ bets were consistently high or low across trials.

Interrater Reliability

Many behavioral measures involve significant judgment on the part of an observer or a rater. Interrater reliability is the extent to which different observers are consistent in their judgments. For example, if you were interested in measuring university students’ social skills, you could make video recordings of them as they interacted with another student whom they are meeting for the first time. Then you could have two or more observers watch the videos and rate each student’s level of social skills. To the extent that each participant does, in fact, have some level of social skills that can be detected by an attentive observer, different observers’ ratings should be highly correlated with each other.

Validity , another key element of assessing measurement quality, is the extent to which the scores from a measure represent the variable they are intended to. But how do researchers make this judgment? We have already considered one factor that they take into account—reliability. When a measure has good test-retest reliability and internal consistency, researchers should be more confident that the scores represent what they are supposed to. There has to be more to it, however, because a measure can be extremely reliable but have no validity whatsoever. As an absurd example, imagine someone who believes that people’s index finger length reflects their self-esteem and therefore tries to measure self-esteem by holding a ruler up to people’s index fingers. Although this measure would have extremely good test-retest reliability, it would have absolutely no validity. The fact that one person’s index finger is a centimeter longer than another’s would indicate nothing about which one had higher self-esteem.

Discussions of validity usually divide it into several distinct “types.” But a good way to interpret these types is that they are other kinds of evidence—in addition to reliability—that should be taken into account when judging the validity of a measure.

Face validity

Face validity is the extent to which a measurement method appears “on its face” to measure the construct of interest. Most people would expect a self-esteem questionnaire to include items about whether they see themselves as a person of worth and whether they think they have good qualities. So a questionnaire that included these kinds of items would have good face validity. The finger-length method of measuring self-esteem, on the other hand, seems to have nothing to do with self-esteem and therefore has poor face validity. Although face validity can be assessed quantitatively—for example, by having a large sample of people rate a measure in terms of whether it appears to measure what it is intended to—it is usually assessed informally.

Face validity is at best a very weak kind of evidence that a measurement method is measuring what it is supposed to. One reason is that it is based on people’s intuitions about human behavior, which are frequently wrong. It is also the case that many established measures in psychology work quite well despite lacking face validity. The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 (MMPI-2) measures many personality characteristics and disorders by having people decide whether each of over 567 different statements applies to them—where many of the statements do not have any obvious relationship to the construct that they measure. For example, the items “I enjoy detective or mystery stories” and “The sight of blood doesn’t frighten me or make me sick” both measure the suppression of aggression. In this case, it is not the participants’ literal answers to these questions that are of interest, but rather whether the pattern of the participants’ responses to a series of questions matches those of individuals who tend to suppress their aggression.

Content validity

Content validity is the extent to which a measure “covers” the construct of interest. For example, if a researcher conceptually defines test anxiety as involving both sympathetic nervous system activation (leading to nervous feelings) and negative thoughts, then his measure of test anxiety should include items about both nervous feelings and negative thoughts. Or consider that attitudes are usually defined as involving thoughts, feelings, and actions toward something. By this conceptual definition, a person has a positive attitude toward exercise to the extent that they think positive thoughts about exercising, feels good about exercising, and actually exercises. So to have good content validity, a measure of people’s attitudes toward exercise would have to reflect all three of these aspects. Like face validity, content validity is not usually assessed quantitatively. Instead, it is assessed by carefully checking the measurement method against the conceptual definition of the construct.

Criterion validity

Criterion validity is the extent to which people’s scores on a measure are correlated with other variables (known as criteria) that one would expect them to be correlated with. For example, people’s scores on a new measure of test anxiety should be negatively correlated with their performance on an important school exam. If it were found that people’s scores were in fact negatively correlated with their exam performance, then this would be a piece of evidence that these scores really represent people’s test anxiety. But if it were found that people scored equally well on the exam regardless of their test anxiety scores, then this would cast doubt on the validity of the measure.

A criterion can be any variable that one has reason to think should be correlated with the construct being measured, and there will usually be many of them. For example, one would expect test anxiety scores to be negatively correlated with exam performance and course grades and positively correlated with general anxiety and with blood pressure during an exam. Or imagine that a researcher develops a new measure of physical risk taking. People’s scores on this measure should be correlated with their participation in “extreme” activities such as snowboarding and rock climbing, the number of speeding tickets they have received, and even the number of broken bones they have had over the years. When the criterion is measured at the same time as the construct, criterion validity is referred to as concurrent validity ; however, when the criterion is measured at some point in the future (after the construct has been measured), it is referred to as predictive validity (because scores on the measure have “predicted” a future outcome).

Discriminant validity

Discriminant validity , on the other hand, is the extent to which scores on a measure are not correlated with measures of variables that are conceptually distinct. For example, self-esteem is a general attitude toward the self that is fairly stable over time. It is not the same as mood, which is how good or bad one happens to be feeling right now. So people’s scores on a new measure of self-esteem should not be very highly correlated with their moods. If the new measure of self-esteem were highly correlated with a measure of mood, it could be argued that the new measure is not really measuring self-esteem; it is measuring mood instead.

Increasing the reliability and validity of measures

We have reviewed the types of errors and how to evaluate our measures based on reliability and validity considerations. However, what can we do while selecting or creating our tool so that we minimize the potential of errors? Many of our options were covered in our discussion about reliability and validity. Nevertheless, the following table provides a quick summary of things that you should do when creating or selecting a measurement tool.

- In measurement, two types of errors can occur: systematic, which we might be able to predict, and random, which are difficult to predict but can sometimes be addressed during statistical analysis.

- There are two distinct criteria by which researchers evaluate their measures: reliability and validity. Reliability is consistency across time (test-retest reliability), across items (internal consistency), and across researchers (interrater reliability). Validity is the extent to which the scores actually represent the variable they are intended to.

- Validity is a judgment based on various types of evidence. The relevant evidence includes the measure’s reliability, whether it covers the construct of interest, and whether the scores it produces are correlated with other variables they are expected to be correlated with and not correlated with variables that are conceptually distinct.

- Once you have used a measure, you should reevaluate its reliability and validity based on your new data. Remember that the assessment of reliability and validity is an ongoing process.

- Provide a clear statement regarding the reliability and validity of these tools. What strengths did you notice? What were the limitations?

- Think about your target population . Are there changes that need to be made in order for one of these tools to be appropriate for your population?

- If you decide to create your own tool, how will you assess its validity and reliability?

11.5 Ethical and social justice considerations for measurement

- Identify potential cultural, ethical, and social justice issues in measurement.