- All subject areas

- Agricultural and Biological Sciences

- Arts and Humanities

- Biochemistry, Genetics and Molecular Biology

- Business, Management and Accounting

- Chemical Engineering

- Computer Science

- Decision Sciences

- Earth and Planetary Sciences

- Economics, Econometrics and Finance

- Engineering

- Environmental Science

- Health Professions

- Immunology and Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics

- Multidisciplinary

- Neuroscience

- Pharmacology, Toxicology and Pharmaceutics

- Physics and Astronomy

- Social Sciences

- All subject categories

- Acoustics and Ultrasonics

- Advanced and Specialized Nursing

- Aerospace Engineering

- Agricultural and Biological Sciences (miscellaneous)

- Agronomy and Crop Science

- Algebra and Number Theory

- Analytical Chemistry

- Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine

- Animal Science and Zoology

- Anthropology

- Applied Mathematics

- Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology

- Applied Psychology

- Aquatic Science

- Archeology (arts and humanities)

- Architecture

- Artificial Intelligence

- Arts and Humanities (miscellaneous)

- Assessment and Diagnosis

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atmospheric Science

- Atomic and Molecular Physics, and Optics

- Automotive Engineering

- Behavioral Neuroscience

- Biochemistry

- Biochemistry, Genetics and Molecular Biology (miscellaneous)

- Biochemistry (medical)

- Bioengineering

- Biological Psychiatry

- Biomaterials

- Biomedical Engineering

- Biotechnology

- Building and Construction

- Business and International Management

- Business, Management and Accounting (miscellaneous)

- Cancer Research

- Cardiology and Cardiovascular Medicine

- Care Planning

- Cell Biology

- Cellular and Molecular Neuroscience

- Ceramics and Composites

- Chemical Engineering (miscellaneous)

- Chemical Health and Safety

- Chemistry (miscellaneous)

- Chiropractics

- Civil and Structural Engineering

- Clinical Biochemistry

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Colloid and Surface Chemistry

- Communication

- Community and Home Care

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Complementary and Manual Therapy

- Computational Mathematics

- Computational Mechanics

- Computational Theory and Mathematics

- Computer Graphics and Computer-Aided Design

- Computer Networks and Communications

- Computer Science Applications

- Computer Science (miscellaneous)

- Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition

- Computers in Earth Sciences

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Conservation

- Control and Optimization

- Control and Systems Engineering

- Critical Care and Intensive Care Medicine

- Critical Care Nursing

- Cultural Studies

- Decision Sciences (miscellaneous)

- Dental Assisting

- Dental Hygiene

- Dentistry (miscellaneous)

- Dermatology

- Development

- Developmental and Educational Psychology

- Developmental Biology

- Developmental Neuroscience

- Discrete Mathematics and Combinatorics

- Drug Discovery

- Drug Guides

- Earth and Planetary Sciences (miscellaneous)

- Earth-Surface Processes

- Ecological Modeling

- Ecology, Evolution, Behavior and Systematics

- Economic Geology

- Economics and Econometrics

- Economics, Econometrics and Finance (miscellaneous)

- Electrical and Electronic Engineering

- Electrochemistry

- Electronic, Optical and Magnetic Materials

- Emergency Medical Services

- Emergency Medicine

- Emergency Nursing

- Endocrine and Autonomic Systems

- Endocrinology

- Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism

- Energy Engineering and Power Technology

- Energy (miscellaneous)

- Engineering (miscellaneous)

- Environmental Chemistry

- Environmental Engineering

- Environmental Science (miscellaneous)

- Epidemiology

- Experimental and Cognitive Psychology

- Family Practice

- Filtration and Separation

- Fluid Flow and Transfer Processes

- Food Animals

- Food Science

- Fuel Technology

- Fundamentals and Skills

- Gastroenterology

- Gender Studies

- Genetics (clinical)

- Geochemistry and Petrology

- Geography, Planning and Development

- Geometry and Topology

- Geotechnical Engineering and Engineering Geology

- Geriatrics and Gerontology

- Gerontology

- Global and Planetary Change

- Hardware and Architecture

- Health Informatics

- Health Information Management

- Health Policy

- Health Professions (miscellaneous)

- Health (social science)

- Health, Toxicology and Mutagenesis

- History and Philosophy of Science

- Horticulture

- Human Factors and Ergonomics

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Immunology and Allergy

- Immunology and Microbiology (miscellaneous)

- Industrial and Manufacturing Engineering

- Industrial Relations

- Infectious Diseases

- Information Systems

- Information Systems and Management

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Insect Science

- Instrumentation

- Internal Medicine

- Issues, Ethics and Legal Aspects

- Leadership and Management

- Library and Information Sciences

- Life-span and Life-course Studies

- Linguistics and Language

- Literature and Literary Theory

- LPN and LVN

- Management Information Systems

- Management, Monitoring, Policy and Law

- Management of Technology and Innovation

- Management Science and Operations Research

- Materials Chemistry

- Materials Science (miscellaneous)

- Maternity and Midwifery

- Mathematical Physics

- Mathematics (miscellaneous)

- Mechanical Engineering

- Mechanics of Materials

- Media Technology

- Medical and Surgical Nursing

- Medical Assisting and Transcription

- Medical Laboratory Technology

- Medical Terminology

- Medicine (miscellaneous)

- Metals and Alloys

- Microbiology

- Microbiology (medical)

- Modeling and Simulation

- Molecular Biology

- Molecular Medicine

- Nanoscience and Nanotechnology

- Nature and Landscape Conservation

- Neurology (clinical)

- Neuropsychology and Physiological Psychology

- Neuroscience (miscellaneous)

- Nuclear and High Energy Physics

- Nuclear Energy and Engineering

- Numerical Analysis

- Nurse Assisting

- Nursing (miscellaneous)

- Nutrition and Dietetics

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Therapy

- Ocean Engineering

- Oceanography

- Oncology (nursing)

- Ophthalmology

- Oral Surgery

- Organic Chemistry

- Organizational Behavior and Human Resource Management

- Orthodontics

- Orthopedics and Sports Medicine

- Otorhinolaryngology

- Paleontology

- Parasitology

- Pathology and Forensic Medicine

- Pathophysiology

- Pediatrics, Perinatology and Child Health

- Periodontics

- Pharmaceutical Science

- Pharmacology

- Pharmacology (medical)

- Pharmacology (nursing)

- Pharmacology, Toxicology and Pharmaceutics (miscellaneous)

- Physical and Theoretical Chemistry

- Physical Therapy, Sports Therapy and Rehabilitation

- Physics and Astronomy (miscellaneous)

- Physiology (medical)

- Plant Science

- Political Science and International Relations

- Polymers and Plastics

- Process Chemistry and Technology

- Psychiatry and Mental Health

- Psychology (miscellaneous)

- Public Administration

- Public Health, Environmental and Occupational Health

- Pulmonary and Respiratory Medicine

- Radiological and Ultrasound Technology

- Radiology, Nuclear Medicine and Imaging

- Rehabilitation

- Religious Studies

- Renewable Energy, Sustainability and the Environment

- Reproductive Medicine

- Research and Theory

- Respiratory Care

- Review and Exam Preparation

- Reviews and References (medical)

- Rheumatology

- Safety Research

- Safety, Risk, Reliability and Quality

- Sensory Systems

- Signal Processing

- Small Animals

- Social Psychology

- Social Sciences (miscellaneous)

- Social Work

- Sociology and Political Science

- Soil Science

- Space and Planetary Science

- Spectroscopy

- Speech and Hearing

- Sports Science

- Statistical and Nonlinear Physics

- Statistics and Probability

- Statistics, Probability and Uncertainty

- Strategy and Management

- Stratigraphy

- Structural Biology

- Surfaces and Interfaces

- Surfaces, Coatings and Films

- Theoretical Computer Science

- Tourism, Leisure and Hospitality Management

- Transplantation

- Transportation

- Urban Studies

- Veterinary (miscellaneous)

- Visual Arts and Performing Arts

- Waste Management and Disposal

- Water Science and Technology

- All regions / countries

- Asiatic Region

- Eastern Europe

- Latin America

- Middle East

- Northern America

- Pacific Region

- Western Europe

- ARAB COUNTRIES

- IBEROAMERICA

- NORDIC COUNTRIES

- Afghanistan

- Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Brunei Darussalam

- Czech Republic

- Dominican Republic

- Netherlands

- New Caledonia

- New Zealand

- Papua New Guinea

- Philippines

- Puerto Rico

- Russian Federation

- Saudi Arabia

- South Africa

- South Korea

- Switzerland

- Syrian Arab Republic

- Trinidad and Tobago

- United Arab Emirates

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Vatican City State

- Book Series

- Conferences and Proceedings

- Trade Journals

- Citable Docs. (3years)

- Total Cites (3years)

| Title | Type | --> | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | journal | 106.094 Q1 | 211 | 49 | 124 | 4844 | 35427 | 89 | 381.89 | 98.86 | 43.95 | ||

| 2 | journal | 37.044 Q1 | 39 | 3 | 13 | 897 | 955 | 13 | 100.11 | 299.00 | 27.78 | ||

| 3 | journal | 35.910 Q1 | 508 | 123 | 336 | 11462 | 13599 | 153 | 34.50 | 93.19 | 29.41 | ||

| 4 | journal | 30.448 Q1 | 306 | 47 | 136 | 3645 | 2240 | 136 | 11.14 | 77.55 | 26.67 | ||

| 5 | journal | 26.837 Q1 | 505 | 105 | 304 | 10805 | 10951 | 163 | 31.23 | 102.90 | 44.33 | ||

| 6 | journal | 24.342 Q1 | 892 | 439 | 1496 | 32820 | 53447 | 1207 | 31.30 | 74.76 | 40.19 | ||

| 7 | journal | 22.399 Q1 | 391 | 239 | 731 | 8584 | 13091 | 153 | 19.72 | 35.92 | 34.15 | ||

| 8 | journal | 22.344 Q1 | 359 | 95 | 353 | 6242 | 4811 | 351 | 10.33 | 65.71 | 23.89 | ||

| 9 | journal | 21.836 Q1 | 184 | 117 | 335 | 8842 | 13775 | 196 | 31.17 | 75.57 | 26.86 | ||

| 10 | journal | 21.048 Q1 | 217 | 127 | 400 | 9888 | 10807 | 183 | 28.36 | 77.86 | 38.85 | ||

| 11 | journal | 20.544 Q1 | 1184 | 1388 | 4522 | 14603 | 107246 | 1824 | 21.69 | 10.52 | 38.26 | ||

| 12 | journal | 19.139 Q1 | 352 | 83 | 227 | 5043 | 1938 | 221 | 7.00 | 60.76 | 16.91 | ||

| 13 | journal | 19.045 Q1 | 630 | 595 | 1363 | 16478 | 36243 | 729 | 27.23 | 27.69 | 43.99 | ||

| 14 | journal | 18.663 Q1 | 71 | 0 | 19 | 0 | 963 | 19 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| 15 | journal | 18.587 Q1 | 23 | 11 | 16 | 0 | 802 | 16 | 47.57 | 0.00 | 81.69 | ||

| 16 | journal | 18.530 Q1 | 215 | 83 | 261 | 4493 | 2531 | 258 | 7.04 | 54.13 | 17.80 | ||

| 17 | journal | 18.509 Q1 | 1391 | 3770 | 8037 | 74917 | 160102 | 3840 | 19.40 | 19.87 | 38.12 | ||

| 18 | journal | 18.117 Q1 | 511 | 485 | 1066 | 13393 | 17008 | 461 | 13.24 | 27.61 | 35.19 | ||

| 19 | journal | 17.828 Q1 | 833 | 271 | 851 | 115878 | 50519 | 819 | 49.76 | 427.59 | 30.50 | ||

| 20 | journal | 17.701 Q1 | 223 | 75 | 273 | 3371 | 1946 | 268 | 6.24 | 44.95 | 13.84 | ||

| 21 | journal | 17.654 Q1 | 234 | 108 | 410 | 6448 | 4495 | 409 | 8.04 | 59.70 | 16.43 | ||

| 22 | journal | 17.507 Q1 | 398 | 178 | 590 | 11546 | 12604 | 360 | 19.83 | 64.87 | 41.91 | ||

| 23 | journal | 17.497 Q1 | 229 | 229 | 609 | 6629 | 16808 | 379 | 26.18 | 28.95 | 29.53 | ||

| 24 | journal | 17.300 Q1 | 639 | 336 | 654 | 13672 | 13100 | 504 | 19.88 | 40.69 | 37.01 | ||

| 25 | journal | 16.061 Q1 | 388 | 36 | 103 | 14097 | 4303 | 99 | 42.66 | 391.58 | 14.94 | ||

| 26 | journal | 16.009 Q1 | 467 | 169 | 540 | 11148 | 13815 | 304 | 23.17 | 65.96 | 36.44 | ||

| 27 | journal | 15.966 Q1 | 264 | 102 | 252 | 19168 | 11266 | 244 | 38.64 | 187.92 | 24.30 | ||

| 28 | journal | 15.827 Q1 | 140 | 106 | 297 | 4359 | 4041 | 62 | 12.99 | 41.12 | 41.35 | ||

| 29 | journal | 15.620 Q1 | 328 | 23 | 84 | 4178 | 2696 | 83 | 27.02 | 181.65 | 40.68 | ||

| 30 | journal | 14.943 Q1 | 115 | 16 | 42 | 403 | 896 | 41 | 24.10 | 25.19 | 77.78 | ||

| 31 | journal | 14.796 Q1 | 388 | 400 | 978 | 11477 | 15900 | 588 | 17.52 | 28.69 | 33.83 | ||

| 32 | journal | 14.780 Q1 | 123 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 374 | 11 | 12.56 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||

| 33 | journal | 14.707 Q1 | 32 | 46 | 35 | 4815 | 2160 | 34 | 61.71 | 104.67 | 36.44 | ||

| 34 | journal | 14.618 Q1 | 160 | 70 | 247 | 587 | 5353 | 230 | 21.11 | 8.39 | 58.79 | ||

| 35 | journal | 14.605 Q1 | 109 | 23 | 72 | 5797 | 1938 | 70 | 14.90 | 252.04 | 45.57 | ||

| 36 | journal | 14.577 Q1 | 419 | 262 | 637 | 10044 | 17562 | 466 | 27.42 | 38.34 | 28.93 | ||

| 37 | journal | 14.293 Q1 | 421 | 123 | 346 | 10202 | 6211 | 207 | 17.40 | 82.94 | 32.86 | ||

| 38 | journal | 14.231 Q1 | 558 | 306 | 834 | 9499 | 20730 | 593 | 24.08 | 31.04 | 24.85 | ||

| 39 | journal | 14.175 Q1 | 210 | 28 | 92 | 3163 | 1260 | 86 | 10.59 | 112.96 | 42.59 | ||

| 40 | journal | 13.942 Q1 | 294 | 144 | 670 | 5180 | 12698 | 362 | 18.81 | 35.97 | 39.02 | ||

| 41 | book series | 13.670 Q1 | 210 | 14 | 42 | 3772 | 1271 | 39 | 23.96 | 269.43 | 26.09 | ||

| 42 | journal | 13.655 Q1 | 311 | 89 | 563 | 4857 | 6315 | 559 | 11.14 | 54.57 | 23.11 | ||

| 43 | journal | 13.609 Q1 | 165 | 93 | 250 | 5332 | 1699 | 250 | 6.02 | 57.33 | 15.88 | ||

| 44 | journal | 13.578 Q1 | 455 | 233 | 688 | 15608 | 13409 | 550 | 16.89 | 66.99 | 40.35 | ||

| 45 | journal | 13.315 Q1 | 136 | 180 | 471 | 6682 | 12109 | 368 | 24.27 | 37.12 | 26.28 | ||

| 46 | journal | 13.080 Q1 | 260 | 243 | 827 | 1865 | 14374 | 679 | 16.58 | 7.67 | 62.53 | ||

| 47 | journal | 12.511 Q1 | 635 | 252 | 983 | 61439 | 44032 | 979 | 38.71 | 243.81 | 32.40 | ||

| 48 | journal | 12.324 Q1 | 81 | 55 | 137 | 2838 | 862 | 137 | 6.20 | 51.60 | 17.36 | ||

| 49 | journal | 12.294 Q1 | 46 | 62 | 154 | 8174 | 4174 | 86 | 27.10 | 131.84 | 31.14 | ||

| 50 | journal | 12.288 Q1 | 44 | 60 | 79 | 4858 | 3323 | 78 | 42.06 | 80.97 | 33.06 |

Follow us on @ScimagoJR Scimago Lab , Copyright 2007-2024. Data Source: Scopus®

Cookie settings

Cookie Policy

Legal Notice

Privacy Policy

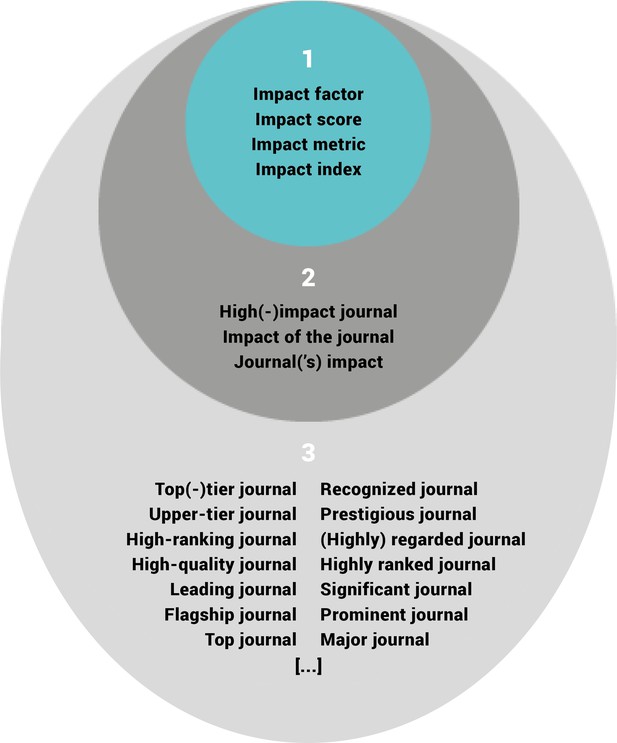

What is a Good Impact Factor for a Journal?

- Research Process

A good journal impact factor (IF) is often the main consideration for researchers when they’re looking for a place to publish their work. Many researchers assume that a high impact factor indicates a more prestigious journal.

Updated on February 22, 2024

A good journal impact factor (IF) is often the main consideration for researchers when they’re looking for a place to publish their work. Many researchers assume that a high impact factor indicates a more prestigious journal. And that means more recognition for the manuscript author(s).

So, by that logic, the higher the impact factor, the better the journal, right?

Well, it’s not that simple.

In principle, a higher IF is better than a lower IF, but there are many conditions, variations, and other issues to consider.

There’s no single determinant of what makes a good journal impact factor. It depends on the field of research, and what you mean by “good.” What is “good” for a breakthrough immunology study may not apply as “good” for an incremental regional economics study.

Using impact factors in the academic world to rank journals remains controversial. The San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment (DORA) , for example, tried to tackle the issue of over-reliance on journal IFs when evaluating published research.

Yet researchers continue to associate a good IF with better quality research. So, until DORA or others develop a better solution, we’re stuck with the IF, simplistic as it may be.

Read on to increase your understanding of impact factors and learn what’s a good one for your research.

First, what’s an impact factor?

A journal impact factor is a metric that assesses the citation rate of articles published in a particular journal over a specific time – that’s usually 2 years (see below).

For example, an IF of 3 means that published articles have been cited on average 3 times during the previous 2 years.

How impact factors are calculated

The IF for a particular year is calculated as the ratio of the total times the journal’s articles were cited in the previous 2 years to the total citable items it published in those 2 years.

For example, in 2018, Nature had an IF of 43.070. That's a good journal impact factor. This is calculated as follows:

(Adapted from https://clarivate.libguides.com/jcr )

(Source: 2018 Journal Citation Reports)

Clarivate Analytics annually computes IFs for journals indexed in Web of Science. These scores are then collectively published in the Journal Citation Reports (JCR) database.

Clarivate publishes two different JCR databases every year. The Science Citation Index (SCI) is for the STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) disciplines, and the Social Science Citation Index (SSCI) is for, you guessed it, the social sciences. These are the only acceptable and reputable sources for impact factors out there: If your journal is using another index, then beware – it could be predatory .

Types of impact factors and metrics

In addition to the 2-year impact factor, Clarivate offers metrics for short-, medium-, and long-term analysis of a JCR journal’s performance. These metrics include:

- Immediacy index – Average number of times an article is cited during the same year it’s published.

- Citing and cited half-life – Median age of citations produced and received by a journal, respectively, during the current JCR year.

- 5-year impact factor – Average number of times articles published in a journal during the past 5 years have been cited in the current JCR year.

- Eigenfactor Score (ES) – Similar to the 5-year impact factor; differences are that (ES) eliminates self-citations and considers the importance of citations received by a journal.

- Article influence score – Derived from the ES; measures the average influence of each article published in a journal.

Journal ranking within a specific subject category can also be indicated by quartiles. Many universities around the world prefer the use of these metrics rather than raw IF for selecting journals. Four quartiles rank journals from highest to lowest based on the impact factor: Q1, Q2, Q3, and Q4.

Q1 comprises the most (statistically) prestigious journals within the subject category; i.e., the top 25% of the journals on the list. Q2 journals fall in the 25%–50% group, Q3 journals in the 50%–75% group, and finally, Q4 in the 75%–100% group.

Numbers = status, and many authors, or their institutions, insist on publication in a Q1 or at least a Q2 journal.

An alternative ranking system, and one that is free to access, Scimago Journal & Country Rank , also uses quartiles. Be sure not to confuse the two.

OK, back to the main question: What’s a good impact factor?

As mentioned, separate JCR databases are published for STEM and social sciences.

Discrepancies in fields

The main reason is that there are wide discrepancies in impact factor scores across different research fields. Some of the likely causes for these discrepancies are:

- Differences in citation behavior in different research fields; e.g., review articles tend to attract more citations than research articles, and the tendency to cite books in the social sciences.

- Differences in types of research; e.g., interdisciplinary and basic research attract more citations than intradisciplinary and applied research.

- Differences in field coverage by JCR; e.g., more in-depth coverage of STEM fields compared with humanities and the social sciences.

To put things into perspective, data prepared by SCI Journal for the 2018/2019 journal impact factor rankings are shown in this table.

Source: scijournal.org

The table illustrates where a journal subject area ranks in the four classes: top 80%, top 60%, top 40%, and top 20%. Outliers were removed for the sake of cleaner data.

STEM impact factors

The data demonstrate how journals for subject areas show a range of impact factors.

Large fields, such as the life sciences, generally have higher IFs. They get cited more, so that makes sense. For example, it's natural that a study on a vaccine breakthrough will lead to more citations than a study on community development.

This obviously skews the use of impact factors when assessing researchers across a university. We can’t all keep up with the biologists!

For example, the top-ranked journal by Clarivate in 2019 was CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, which had a remarkably high IF of 292.278. The New England Journal of Medicine , which has long been a prestigious journal, came in second with a high IF of 74.699. Those are amazingly good journal impact factors.

Conversely, reputable journals in smaller fields, such as mathematics, tend to have lower impact factors than the natural sciences.

For example, the 2019 JCR impact factors for respectable mathematical journals such as Inventiones Mathematicae and Duke Mathematical Journal were 2.986 and 2.194, respectively.

Social sciences impact factors

As for the social sciences, you could simply argue they’re “less popular” than the natural sciences. So, their reputable journals also tend to have lower impact factors.

For example, well-regarded journals such as the American Journal of Sociology and the British Journal of Sociology had JCR 2019 impact factors of 3.232 and 2.908, respectively. Those are good impact factors for the social sciences but would look rather low for STEM unless it was a regional or niche topic.

Therefore, what may be seen as an excellent impact factor in mathematics and the social sciences may be viewed as way below average in the life sciences.

That’s not to say the social sciences are less important. It just means they’re comparably researched and cited less.

Niche and specialized impact factors

The comparison doesn’t end there. Another aspect that shouldn’t be overlooked is the research subfield. Journals in, say, a physics subfield such as astronomy have a different impact factor than journals in fluid dynamics.

For example, two well-known astrophysics journals, MNRAS and Astrophysical Journal , had JCR 2019 IFs of 5.356 and 5.745, respectively. Meanwhile, two respectable journals in fluid dynamics, Journal of Fluid Mechanics and Physics of Fluids had JCR 2019 IFs of 3.354 and 3.514, respectively.

They may not be in The New England Journal of Medicine territory, but all are reputable journals.

So, all things considered, what is a good journal impact factor?

You have to look at the bigger picture here because there’s a lot more to consider than the single numeric representation.

If you’re in a field/subfield with high-impact-factor journals, it’s only logical that the cutoff for a good IF will also be high. And, of course, it’ll be lower for a field/subfield with lower impact factor journals.

Impact factor statistics should, thus, be interpreted relatively and with caution, because the scores represented are not absolute.

A good impact factor is either, in short, what your institution or you say it is. Otherwise, it’s one that's sufficient to connote prestige while still being a good forum for your research to be read and cited.

Let’s look at a few of the other factors, apart from IF, to help you choose your target journal.

Pros and cons of using impact factor to judge a journal’s quality

The impact factor was used initially to rank journals, which will then help you decide on which one to which to submit your research. Some of the pros of an IF include:

- Easily accessible

- Gives a general picture of a journal’s prestige and reputation

- Is pretty good for comparison within a field if not across fields

- Appeals to people and institutions that like rankings and numbers

Despite its popularity, the impact factor is clearly a flawed metric, and its use to judge if a journal is good is criticized. That’s what we’ve seen with DORA, among plenty of others.

In addition to the previously mentioned shortcoming of not being able to use the impact factor for comparing journals across fields, other cons include:

- Ambiguous description of what “citable items” are

- Lack of consideration of highly cited papers resulting in skewed citation distributions

- Encouragement of self-citations by journals

The criticism is nothing new (see Kurmis, 2003 , among others). But we’ve got to live with it until there’s something better.

On a personal note, we’re rather tired of seeing the great stress of publishing in a Q1 journal that’s placed on researchers. Especially those from certain economies that pressure their researchers to publish when they’d be better off fostering good, reflective, valuable research.

So here are some other factors with impact, even if they’re not impact factors.

Things other than impact factor to consider when choosing a journal

A good impact factor may be a requirement by your institution. But it shouldn’t be the only aspect you consider when choosing where to publish your manuscript.

Aims and scope

Another key factor is whether the work to be published fits within the aims and scope of the journal.

You can determine this by analyzing the journal’s subjects covered, types of articles published, and peer-review process. Some very targeted journals would welcome your research with open arms.

Target audience

An additional factor to consider is the target audience. Who is likely to read and cite the article? Where do these researchers publish? This can facilitate the shortlisting of some journals.

Other factors, apart from IF, for choosing your target journal

Other tips for choosing a journal include:

- Find journals that publish research that’s similar to yours, especially if it’s quite specialized

- Read as many published articles as you can in your target journal

- Go through your list of references to see which journals have the most citations

- Find out where fellow researchers and colleagues publish

Well-known publishers like Springer and Elsevier also list factors for choosing a journal.

Scimago as an alternative

Scimago Journal Rank (SJR) , as mentioned above, is a useful portal that scores and ranks journals, which are indexed in Elsevier’s Scopus database, based on citation data.

The SJR indicator (PDF) not only measures the citations received from a journal but also the importance or prestige of the journal where these citations come from. It can be used to view journal rankings by subject category and compare journals within the same field.

And here’s a great scholarly article with useful references that provide information on how to identify and avoid submitting to predatory journals.

Conclusion on what’s a good impact factor, especially for you and your research

What makes a good impact factor boils down to the field of research and the host of arbiters of “good.” Highly reputable journals may have low impact factors not because they lack credibility, but because they’re in specialized/niche fields with low citations.

The interpretation of what is a “good” journal impact factor varies. Possibly due to the ambitious nature of some researchers or the ignorance of others.

An IF can indeed serve as a starting point during decision-making, but, if possible, and if you don’t have to meet some arbitrary target, more emphasis should be paid to publishing high-quality research.

The prevailing mindset should be that a journal stands to benefit more from the good-quality research it publishes rather than the other way around.

The AJE Team

See our "Privacy Policy"

Find the right journal for your work and with your desired impact factor

AJE will compile a report of three Journal Recommendations specifically for your scientific manuscript. This way, you can get pursue the impact factor you want and/or pursue which journal is most suitable or is likely to publish your work faster.

- Skip to Guides Search

- Skip to breadcrumb

- Skip to main content

- Skip to footer

- Skip to chat link

- Report accessibility issues and get help

- Go to Penn Libraries Home

- Go to Franklin catalog

Research Impact and Citation Analysis

- Compile Departmental Publications

- Curate Researcher Publications

- Discover Potential Collaborators

Compare Journals

- Explore a Document's Impact

- Calculate H-Index

Counterpoints

How do metrics like journal impact factor drive editorial choices, and even prompt manipulative behavior on the part of publishers? See Gaye Tuchman's 2012 article on Inside Higher Ed , "Commodifying the Academic Self."

Limitations | Comparing Journal Impact Factor | Counterpoints

Limitations

Journal Impact Factor is only one metric by which journals can be compared. What are some other ways to determine a journal's impact, quality, or relevance?

How many patents cite a journal? You can find this out at Lens.org, a free agglomeration database which harvests bibliographic data from PubMed, Crossref, and other sources. Or how about public policy documents, government reports, and statutes?

Interested in reviewing journal quality? One way is to browse the journal's contents. Review the subject matter, and note its relevance to your work. Pick a sampling of articles and study their research methods sections -- do the methods seem rigorous? You can also check the journal's editorial policies around rigor. Does the journal employ statistical reviewers, if relevant?

Cabell's Journalytics and Predatory Reports give a number of potential factors to review while evaluating journals. Does a journal falsely claim to be indexed in an academic database? Is there a clearly stated peer review policy on the journal website? Does one managing editor appear to be the editor for dozens of journals? Is the editorial board listed?

All these and more are questions a researcher should ask when comparing journal impact, quality, and relevance.

Comparing Journal Impact Factor

In this tutorial, we’ll be using Journal Citation Reports (JCR) from Clarivate. JCR has two metrics of interest, journal impact factor (JIF) and the journal citation indicator (JCI).

Journal Impact Factor (JIF) is a Clarivate metric. In any given year, the impact factor of a journal is the average number of citations received per paper published in that journal during the two preceding years. The impact factor is based on two figures: the number of citations to a given journal over the previous two years (A) and the number of research articles and review articles published by that journal over the same two-year period (B), so: A/B = Impact Factor (JCR). There is also a separate 5-year JIF, which applies the same formula for citations to a given journal over the previous five years, rather than two years.

Journal Citation Indicator (JCI) is a three-year average of a field-weighted metric called CNCI, itself a ratio between number of citations to a journal and the number of expected citations to a journal. How the expectations are calculated is a black box which Clarivate does not reveal. The end result of the JCI is a number which is supposed to be comparable across disciplines. If a journal is given a JCI of 1.0, it is exactly the global average for citation impact. If a journal is given 2.0, it’s impact score is twice the average. In other words, Clarivate frames having a higher than 1.0 JCI as desirable.

There are many other ways to evaluate journal quality other than simply using these metrics – please see the Considerations and Context section for more. For now, we’ll look at how to retrieve and compare JIF.

First, connect to Journal Citation Reports . Sign in with your Clarivate credentials (the same ones used to sign into Web of Science) to create saved Favorites lists.

Starting with specific journals

Go to Journals at the top and search for a journal name, Click Enter when your desired result appears, or click “see 1 result” . For our purposes, this is better than than clicking the name of the actual journal when it appears; clicking it would open a new window with information about the journal itself.

Check off the correct box. Your boxes will stay selected until you consciously choose to deselect them at the bottom. So, if you like, you could just get through your list of up to 50 journals for comparison and add them all to a Favorite list at once.

Once you have selected all the journals you’d like to compare, click the Add to Favorites list button. Make a new list if applicable.

If your journal doesn’t come up by name, try using ISSN instead. Search for the journal online or in Franklin Catalog to find their ISSN. Both print and e-issns should be listed for a journal, so it shouldn’t matter.

To view the compared list, go to My Favorites, and click on your list.

You should be able to compare attributes between all of the journals on that list, including journal impact factor.

For additional analysis, you can compare four journals at once using the Compare feature at the bottom of the screen, after the selection phase. This provides both JIF and JCI, but also additional visualizations based on OA, quartiles, etc.

Starting with a journal category

If you don’t know what journals you’d like to compare, but just want to compare a number of journals in a given category, go to Categories at the top, drill down to a category of interest, and click on the number of journals to view their comparison. You can also search for categories in the main search box.

You’ll have the option to explore journals within a category in either the ESCI, the Emerging Sources Citation Index, or a more longstanding index, like the SSCI (Social Sciences Citation Index), SCIE (Science Citation Index-Expanded), and the AHCI (Arts and Humanities Citation Index).

Here you can sort based on JCR, JCI, total citations, or %OA gold. You can also change the JCR year using the filters on the left. If you click on Customize toward the top of the table, you can see other metrics, such as article influence score, normalized Eigenfactor, 5-year JIF, JIF without self-cites, and more. You can also customize which metrics you’d like to see on the screen at once.

You can also click on any one journal name to look at all of these metrics with visualizations for that one journal.

- << Previous: Discover Potential Collaborators

- Next: Explore a Document's Impact >>

- Last Updated: Sep 12, 2023 3:44 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.upenn.edu/bibliometrics

RESEARCH REVIEW International Journal of Multidisciplinary

About the journal.

RESEARCH REVIEW International Journal of Multidisciplinary (RRIJM) is an international Double-blind peer-reviewed [refereed] open access online journal. Too often a journal’s decision to publish a paper is dominated by what the editor/s think is interesting and will gain greater readership-both of which are subjective judgments and lead to decisions which are frustrating and delay the publication of your work. RRIJM will rigorously peer-review your submissions and publish all papers that are judged to be technically sound. Judgments about the importance of any particular paper are then made after publication by the readership (who are the most qualified to determine what is of interest to them).

Most conventional journals publish papers from tightly defined subject areas, making it more difficult for readers from other disciplines to read them. RRIJM has no such barriers, which helps your research reach the entire scientific community.

- Title: RESEARCH REVIEW International Multidisciplinary Research Journal

- ISSN: 2455-3085 (Online)

- Impact Factor: 6.849

- Crossref DOI: 10.31305/rrijm

- Frequency of Publication: Monthly [12 issues per year]

- Languages: English/Hindi/Gujarat [Multiple Languages]

- Accessibility: Open Access

- Peer Review Process: Double Blind Peer Review Process

- Subject: Multidisciplinary

- Plagiarism Checker: Turnitin (License)

- Publication Format: Online

- Contact No.: +91- 99784 40833

- Email: [email protected]

- Old Website: https://old.rrjournals.com/

- New Website: https://rrjournals.com/

- Address: 15, Kalyan Nagar, Shahpur, Ahmedabad, Gujarat 380001

Key Features of RRIJM

- Journal was listed in UGC with Journal No. 44945 (Till 14-06-2019)

- Journal Publishes online every month

- Online article submission

- Standard peer review process

Current Issue

Research on Green Finance: A Bibliometric Analysis

The criminal law policy for the buyers of pornographic content, factors causing water loss in the distribution system at pt air minum giri menang (perseroda), comparative study of swami vivekananda’s educational philosophy and modern educational systems स्वामी विवेकानंद के शैक्षिक दर्शन और आधुनिक शिक्षा प्रणालियों का तुलनात्मक अध्ययन, spatial analysis of population landscape: a case study of scheduled caste population in basti district, sustainability practices and esg scores: a sectoral study of nifty 50 firms, a study of the effect of weight training on athletes' agility વજન તાલીમ દ્વારા ખેલાડીઓની ચપળતા પર થતી અસરનો અભ્યાસ, religion and socialization: the psycho-sociological role of islam in socializing individuals and the muslim community (ummah), a study of the effect of yoga and step aerobic activities on circulatory endurance યોગ અને સ્ટેપ એરોબિક પ્રવૃત્તિઓ દ્વારા રૂધિરાભિસરણ સહનશક્તિ પર થતી અસરનો અભ્યાસ, from eccentric incarnations to dehumanized stereotypes: a reading of malayalam films showcasing the visually impaired, bridging research and resources: bibliometric analysis of international journal of research in special education as a library service model, analysis of the impact of reform movements on indian nationalism भारतीय राष्ट्रवाद पर सुधार आन्दोलनों के प्रभाव का विश्लेषण, perspectives on gender and inequality, ethical implications of ai in criminal justice: balancing efficiency and due process, geographically weighted panel regression (gwpr) and geographically and temporally weighted regression (gtwr) methods in the influence of factors affecting the minimum wage of each province in indonesia, study of drought using the theory of run and hydrological drought index and its relationship to reservoir storage at the batubai dam and pengga dam, analysis of risk factors for delays in the implementation of the meninting dam construction project, west lombok regency, juridical analysis of implementation of multi-purpose financing agreements at pt. sinarmas mataram branch, a study on the portrayal of mythological hybrid forms in modern indian art, recollecting the history of mysore ganjifa: an art historical perspective, beyond the shadows: unveiling the socio-political contribution of women in colonial rajasthan in india, information.

- For Readers

- For Authors

- For Librarians

Make a Submission

RESEARCH REVIEW International Journal of Multidisciplinary is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License .

Click here to go to Old Website

Management Research Review

- Submit your paper

- Author guidelines

- Editorial team

- Indexing & metrics

- Calls for papers & news

Before you start

For queries relating to the status of your paper pre decision, please contact the Editor or Journal Editorial Office. For queries post acceptance, please contact the Supplier Project Manager. These details can be found in the Editorial Team section.

Author responsibilities

Our goal is to provide you with a professional and courteous experience at each stage of the review and publication process. There are also some responsibilities that sit with you as the author. Our expectation is that you will:

- Respond swiftly to any queries during the publication process.

- Be accountable for all aspects of your work. This includes investigating and resolving any questions about accuracy or research integrity .

- Treat communications between you and the journal editor as confidential until an editorial decision has been made.

- Include anyone who has made a substantial and meaningful contribution to the submission (anyone else involved in the paper should be listed in the acknowledgements).

- Exclude anyone who hasn’t contributed to the paper, or who has chosen not to be associated with the research.

- In accordance with COPE’s position statement on AI tools , Large Language Models cannot be credited with authorship as they are incapable of conceptualising a research design without human direction and cannot be accountable for the integrity, originality, and validity of the published work. The author(s) must describe the content created or modified as well as appropriately cite the name and version of the AI tool used; any additional works drawn on by the AI tool should also be appropriately cited and referenced. Standard tools that are used to improve spelling and grammar are not included within the parameters of this guidance. The Editor and Publisher reserve the right to determine whether the use of an AI tool is permissible.

- If your article involves human participants, you must ensure you have considered whether or not you require ethical approval for your research, and include this information as part of your submission. Find out more about informed consent .

Generative AI usage key principles

- Copywriting any part of an article using a generative AI tool/LLM would not be permissible, including the generation of the abstract or the literature review, for as per Emerald’s authorship criteria, the author(s) must be responsible for the work and accountable for its accuracy, integrity, and validity.

- The generation or reporting of results using a generative AI tool/LLM is not permissible, for as per Emerald’s authorship criteria, the author(s) must be responsible for the creation and interpretation of their work and accountable for its accuracy, integrity, and validity.

- The in-text reporting of statistics using a generative AI tool/LLM is not permissible due to concerns over the authenticity, integrity, and validity of the data produced, although the use of such a tool to aid in the analysis of the work would be permissible.

- Copy-editing an article using a generative AI tool/LLM in order to improve its language and readability would be permissible as this mirrors standard tools already employed to improve spelling and grammar, and uses existing author-created material, rather than generating wholly new content, while the author(s) remains responsible for the original work.

- The submission and publication of images created by AI tools or large-scale generative models is not permitted.

Research and publishing ethics

Our editors and employees work hard to ensure the content we publish is ethically sound. To help us achieve that goal, we closely follow the advice laid out in the guidelines and flowcharts on the COPE (Committee on Publication Ethics) website .

We have also developed our research and publishing ethics guidelines . If you haven’t already read these, we urge you to do so – they will help you avoid the most common publishing ethics issues.

A few key points:

- Any manuscript you submit to this journal should be original. That means it should not have been published before in its current, or similar, form. Exceptions to this rule are outlined in our pre-print and conference paper policies . If any substantial element of your paper has been previously published, you need to declare this to the journal editor upon submission. Please note, the journal editor may use Crossref Similarity Check to check on the originality of submissions received. This service compares submissions against a database of 49 million works from 800 scholarly publishers.

- Your work should not have been submitted elsewhere and should not be under consideration by any other publication.

- If you have a conflict of interest, you must declare it upon submission; this allows the editor to decide how they would like to proceed. Read about conflict of interest in our research and publishing ethics guidelines .

- By submitting your work to Emerald, you are guaranteeing that the work is not in infringement of any existing copyright.

Third party copyright permissions

Prior to article submission, you need to ensure you’ve applied for, and received, written permission to use any material in your manuscript that has been created by a third party. Please note, we are unable to publish any article that still has permissions pending. The rights we require are:

- Non-exclusive rights to reproduce the material in the article or book chapter.

- Print and electronic rights.

- Worldwide English-language rights.

- To use the material for the life of the work. That means there should be no time restrictions on its re-use e.g. a one-year licence.

We are a member of the International Association of Scientific, Technical, and Medical Publishers (STM) and participate in the STM permissions guidelines , a reciprocal free exchange of material with other STM publishers. In some cases, this may mean that you don’t need permission to re-use content. If so, please highlight this at the submission stage.

Please take a few moments to read our guide to publishing permissions to ensure you have met all the requirements, so that we can process your submission without delay.

Open access submissions and information

All our journals currently offer two open access (OA) publishing paths; gold open access and green open access.

If you would like to, or are required to, make the branded publisher PDF (also known as the version of record) freely available immediately upon publication, you can select the gold open access route once your paper is accepted.

If you’ve chosen to publish gold open access, this is the point you will be asked to pay the APC (article processing charge) . This varies per journal and can be found on our APC price list or on the editorial system at the point of submission. Your article will be published with a Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 user licence , which outlines how readers can reuse your work.

Alternatively, if you would like to, or are required to, publish open access but your funding doesn’t cover the cost of the APC, you can choose the green open access, or self-archiving, route. As soon as your article is published, you can make the author accepted manuscript (the version accepted for publication) openly available, free from payment and embargo periods.

You can find out more about our open access routes, our APCs and waivers and read our FAQs on our open research page.

Find out about open

Transparency and Openness Promotion (TOP) Guidelines

We are a signatory of the Transparency and Openness Promotion (TOP) Guidelines , a framework that supports the reproducibility of research through the adoption of transparent research practices. That means we encourage you to:

- Cite and fully reference all data, program code, and other methods in your article.

- Include persistent identifiers, such as a Digital Object Identifier (DOI), in references for datasets and program codes. Persistent identifiers ensure future access to unique published digital objects, such as a piece of text or datasets. Persistent identifiers are assigned to datasets by digital archives, such as institutional repositories and partners in the Data Preservation Alliance for the Social Sciences (Data-PASS).

- Follow appropriate international and national procedures with respect to data protection, rights to privacy and other ethical considerations, whenever you cite data. For further guidance please refer to our research and publishing ethics guidelines . For an example on how to cite datasets, please refer to the references section below.

Prepare your submission

Manuscript support services.

We are pleased to partner with Editage, a platform that connects you with relevant experts in language support, translation, editing, visuals, consulting, and more. After you’ve agreed a fee, they will work with you to enhance your manuscript and get it submission-ready.

This is an optional service for authors who feel they need a little extra support. It does not guarantee your work will be accepted for review or publication.

Visit Editage

Manuscript requirements

Before you submit your manuscript, it’s important you read and follow the guidelines below. You will also find some useful tips in our structure your journal submission how-to guide.

|

| Article files should be provided in Microsoft Word format. While you are welcome to submit a PDF of the document alongside the Word file, PDFs alone are not acceptable. LaTeX files can also be used but only if an accompanying PDF document is provided. Acceptable figure file types are listed further below. |

|

| Articles should be between 6000 and 8000 words in length. This includes all text, for example, the structured abstract, references, all text in tables, and figures and appendices. Please allow 280 words for each figure or table. |

|

| A concisely worded title should be provided. |

|

| The names of all contributing authors should be added to the ScholarOne submission; please list them in the order in which you’d like them to be published. Each contributing author will need their own ScholarOne author account, from which we will extract the following details: (institutional preferred). . We will reproduce it exactly, so any middle names and/or initials they want featured must be included. . This should be where they were based when the research for the paper was conducted.In multi-authored papers, it’s important that ALL authors that have made a significant contribution to the paper are listed. Those who have provided support but have not contributed to the research should be featured in an acknowledgements section. You should never include people who have not contributed to the paper or who don’t want to be associated with the research. Read about our for authorship. |

|

| If you want to include these items, save them in a separate Microsoft Word document and upload the file with your submission. Where they are included, a brief professional biography of not more than 100 words should be supplied for each named author. |

|

| Your article must reference all sources of external research funding in the acknowledgements section. You should describe the role of the funder or financial sponsor in the entire research process, from study design to submission. |

|

| All submissions must include a structured abstract, following the format outlined below. These four sub-headings and their accompanying explanations must always be included: The following three sub-headings are optional and can be included, if applicable:

The maximum length of your abstract should be 250 words in total, including keywords and article classification (see the sections below). |

|

| Your submission should include up to 12 appropriate and short keywords that capture the principal topics of the paper. Our how to guide contains some practical guidance on choosing search-engine friendly keywords. Please note, while we will always try to use the keywords you’ve suggested, the in-house editorial team may replace some of them with matching terms to ensure consistency across publications and improve your article’s visibility. |

|

| During the submission process, you will be asked to select a type for your paper; the options are listed below. If you don’t see an exact match, please choose the best fit:

You will also be asked to select a category for your paper. The options for this are listed below. If you don’t see an exact match, please choose the best fit: Reports on any type of research undertaken by the author(s), including: Covers any paper where content is dependent on the author's opinion and interpretation. This includes journalistic and magazine-style pieces. Describes and evaluates technical products, processes or services. Focuses on developing hypotheses and is usually discursive. Covers philosophical discussions and comparative studies of other authors’ work and thinking. Describes actual interventions or experiences within organizations. It can be subjective and doesn’t generally report on research. Also covers a description of a legal case or a hypothetical case study used as a teaching exercise. This category should only be used if the main purpose of the paper is to annotate and/or critique the literature in a particular field. It could be a selective bibliography providing advice on information sources, or the paper may aim to cover the main contributors to the development of a topic and explore their different views. Provides an overview or historical examination of some concept, technique or phenomenon. Papers are likely to be more descriptive or instructional (‘how to’ papers) than discursive. |

|

| Headings must be concise, with a clear indication of the required hierarchy. |

|

| Notes or endnotes should only be used if absolutely necessary. They should be identified in the text by consecutive numbers enclosed in square brackets. These numbers should then be listed, and explained, at the end of the article. |

|

| All figures (charts, diagrams, line drawings, webpages/screenshots, and photographic images) should be submitted electronically. Both colour and black and white files are accepted. |

|

| Tables should be typed and submitted in a separate file to the main body of the article. The position of each table should be clearly labelled in the main body of the article with corresponding labels clearly shown in the table file. Tables should be numbered consecutively in Roman numerals (e.g. I, II, etc.). Give each table a brief title. Ensure that any superscripts or asterisks are shown next to the relevant items and have explanations displayed as footnotes to the table, figure or plate. |

|

| Where tables, figures, appendices, and other additional content are supplementary to the article but not critical to the reader’s understanding of it, you can choose to host these supplementary files alongside your article on Insight, Emerald’s content-hosting platform (this is Emerald's recommended option as we are able to ensure the data remain accessible), or on an alternative trusted online repository. All supplementary material must be submitted prior to acceptance. Emerald recommends that authors use the following two lists when searching for a suitable and trusted repository: , you must submit these as separate files alongside your article. Files should be clearly labelled in such a way that makes it clear they are supplementary; Emerald recommends that the file name is descriptive and that it follows the format ‘Supplementary_material_appendix_1’ or ‘Supplementary tables’. All supplementary material must be mentioned at the appropriate moment in the main text of the article; there is no need to include the content of the file only the file name. A link to the supplementary material will be added to the article during production, and the material will be made available alongside the main text of the article at the point of EarlyCite publication. Please note that Emerald will not make any changes to the material; it will not be copy-edited or typeset, and authors will not receive proofs of this content. Emerald therefore strongly recommends that you style all supplementary material ahead of acceptance of the article. Emerald Insight can host the following file types and extensions: , you should ensure that the supplementary material is hosted on the repository ahead of submission, and then include a link only to the repository within the article. It is the responsibility of the submitting author to ensure that the material is free to access and that it remains permanently available. Where an alternative trusted online repository is used, the files hosted should always be presented as read-only; please be aware that such usage risks compromising your anonymity during the review process if the repository contains any information that may enable the reviewer to identify you; as such, we recommend that all links to alternative repositories are reviewed carefully prior to submission. Please note that extensive supplementary material may be subject to peer review; this is at the discretion of the journal Editor and dependent on the content of the material (for example, whether including it would support the reviewer making a decision on the article during the peer review process). |

|

| All references in your manuscript must be formatted using one of the recognised Harvard styles. You are welcome to use the Harvard style Emerald has adopted – we’ve provided a detailed guide below. Want to use a different Harvard style? That’s fine, our typesetters will make any necessary changes to your manuscript if it is accepted. Please ensure you check all your citations for completeness, accuracy and consistency.

References to other publications in your text should be written as follows: , 2006) Please note, ‘ ' should always be written in italics.A few other style points. These apply to both the main body of text and your final list of references. At the end of your paper, please supply a reference list in alphabetical order using the style guidelines below. Where a DOI is available, this should be included at the end of the reference. |

|

| Surname, initials (year), , publisher, place of publication. e.g. Harrow, R. (2005), , Simon & Schuster, New York, NY. |

|

| Surname, initials (year), "chapter title", editor's surname, initials (Ed.), , publisher, place of publication, page numbers. e.g. Calabrese, F.A. (2005), "The early pathways: theory to practice – a continuum", Stankosky, M. (Ed.), , Elsevier, New York, NY, pp.15-20. |

|

| Surname, initials (year), "title of article", , volume issue, page numbers. e.g. Capizzi, M.T. and Ferguson, R. (2005), "Loyalty trends for the twenty-first century", , Vol. 22 No. 2, pp.72-80. |

|

| Surname, initials (year of publication), "title of paper", in editor’s surname, initials (Ed.), , publisher, place of publication, page numbers. e.g. Wilde, S. and Cox, C. (2008), “Principal factors contributing to the competitiveness of tourism destinations at varying stages of development”, in Richardson, S., Fredline, L., Patiar A., & Ternel, M. (Ed.s), , Griffith University, Gold Coast, Qld, pp.115-118. |

|

| Surname, initials (year), "title of paper", paper presented at [name of conference], [date of conference], [place of conference], available at: URL if freely available on the internet (accessed date). e.g. Aumueller, D. (2005), "Semantic authoring and retrieval within a wiki", paper presented at the European Semantic Web Conference (ESWC), 29 May-1 June, Heraklion, Crete, available at: http://dbs.uni-leipzig.de/file/aumueller05wiksar.pdf (accessed 20 February 2007). |

|

| Surname, initials (year), "title of article", working paper [number if available], institution or organization, place of organization, date. e.g. Moizer, P. (2003), "How published academic research can inform policy decisions: the case of mandatory rotation of audit appointments", working paper, Leeds University Business School, University of Leeds, Leeds, 28 March. |

|

| (year), "title of entry", volume, edition, title of encyclopaedia, publisher, place of publication, page numbers. e.g. (1926), "Psychology of culture contact", Vol. 1, 13th ed., Encyclopaedia Britannica, London and New York, NY, pp.765-771. (for authored entries, please refer to book chapter guidelines above) |

|

| Surname, initials (year), "article title", , date, page numbers. e.g. Smith, A. (2008), "Money for old rope", , 21 January, pp.1, 3-4. |

|

| (year), "article title", date, page numbers. e.g. (2008), "Small change", 2 February, p.7. |

|

| Surname, initials (year), "title of document", unpublished manuscript, collection name, inventory record, name of archive, location of archive. e.g. Litman, S. (1902), "Mechanism & Technique of Commerce", unpublished manuscript, Simon Litman Papers, Record series 9/5/29 Box 3, University of Illinois Archives, Urbana-Champaign, IL. |

|

| If available online, the full URL should be supplied at the end of the reference, as well as the date that the resource was accessed. Surname, initials (year), “title of electronic source”, available at: persistent URL (accessed date month year). e.g. Weida, S. and Stolley, K. (2013), “Developing strong thesis statements”, available at: https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/588/1/ (accessed 20 June 2018) Standalone URLs, i.e. those without an author or date, should be included either inside parentheses within the main text, or preferably set as a note (Roman numeral within square brackets within text followed by the full URL address at the end of the paper). |

|

| Surname, initials (year), , name of data repository, available at: persistent URL, (accessed date month year). e.g. Campbell, A. and Kahn, R.L. (2015), , ICPSR07218-v4, Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (distributor), Ann Arbor, MI, available at: https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR07218.v4 (accessed 20 June 2018) |

Submit your manuscript

There are a number of key steps you should follow to ensure a smooth and trouble-free submission.

Double check your manuscript

Before submitting your work, it is your responsibility to check that the manuscript is complete, grammatically correct, and without spelling or typographical errors. A few other important points:

- Give the journal aims and scope a final read. Is your manuscript definitely a good fit? If it isn’t, the editor may decline it without peer review.

- Does your manuscript comply with our research and publishing ethics guidelines ?

- Have you cleared any necessary publishing permissions ?

- Have you followed all the formatting requirements laid out in these author guidelines?

- If you need to refer to your own work, use wording such as ‘previous research has demonstrated’ not ‘our previous research has demonstrated’.

- If you need to refer to your own, currently unpublished work, don’t include this work in the reference list.

- Any acknowledgments or author biographies should be uploaded as separate files.

- Carry out a final check to ensure that no author names appear anywhere in the manuscript. This includes in figures or captions.

You will find a helpful submission checklist on the website Think.Check.Submit .

The submission process

All manuscripts should be submitted through our editorial system by the corresponding author.

The only way to submit to the journal is through the journal’s ScholarOne site as accessed via the Emerald website, and not by email or through any third-party agent/company, journal representative, or website. Submissions should be done directly by the author(s) through the ScholarOne site and not via a third-party proxy on their behalf.

A separate author account is required for each journal you submit to. If this is your first time submitting to this journal, please choose the Create an account or Register now option in the editorial system. If you already have an Emerald login, you are welcome to reuse the existing username and password here.

Please note, the next time you log into the system, you will be asked for your username. This will be the email address you entered when you set up your account.

Don't forget to add your ORCiD ID during the submission process. It will be embedded in your published article, along with a link to the ORCiD registry allowing others to easily match you with your work.

Don’t have one yet? It only takes a few moments to register for a free ORCiD identifier .

Visit the ScholarOne support centre for further help and guidance.

What you can expect next

You will receive an automated email from the journal editor, confirming your successful submission. It will provide you with a manuscript number, which will be used in all future correspondence about your submission. If you have any reason to suspect the confirmation email you receive might be fraudulent, please contact the journal editor in the first instance.

Post submission

Review and decision process.

Each submission is checked by the editor. At this stage, they may choose to decline or unsubmit your manuscript if it doesn’t fit the journal aims and scope, or they feel the language/manuscript quality is too low.

If they think it might be suitable for the publication, they will send it to at least two independent referees for double anonymous peer review. Once these reviewers have provided their feedback, the editor may decide to accept your manuscript, request minor or major revisions, or decline your work.

This journal offers an article transfer service. If the editor decides to decline your manuscript, either before or after peer review, they may offer to transfer it to a more relevant Emerald journal in this field. If you accept, your ScholarOne author account, and the accounts of your co-authors, will automatically transfer to the new journal, along with your manuscript and any accompanying peer review reports. However, you will still need to log in to ScholarOne to complete the submission process using your existing username and password. While accepting a transfer does not guarantee the receiving journal will publish your work, an editor will only suggest a transfer if they feel your article is a good fit with the new title.

While all journals work to different timescales, the goal is that the editor will inform you of their first decision within 60 days.

During this period, we will send you automated updates on the progress of your manuscript via our submission system, or you can log in to check on the current status of your paper. Each time we contact you, we will quote the manuscript number you were given at the point of submission. If you receive an email that does not match these criteria, it could be fraudulent and we recommend you contact the journal editor in the first instance.

Manuscript transfer service

Emerald’s manuscript transfer service takes the pain out of the submission process if your manuscript doesn’t fit your initial journal choice. Our team of expert Editors from participating journals work together to identify alternative journals that better align with your research, ensuring your work finds the ideal publication home it deserves. Our dedicated team is committed to supporting authors like you in finding the right home for your research.

If a journal is participating in the manuscript transfer program, the Editor has the option to recommend your paper for transfer. If a transfer decision is made by the Editor, you will receive an email with the details of the recommended journal and the option to accept or reject the transfer. It’s always down to you as the author to decide if you’d like to accept. If you do accept, your paper and any reviewer reports will automatically be transferred to the recommended journals. Authors will then confirm resubmissions in the new journal’s ScholarOne system.

Our Manuscript Transfer Service page has more information on the process.

If your submission is accepted

Open access.

Once your paper is accepted, you will have the opportunity to indicate whether you would like to publish your paper via the gold open access route.

If you’ve chosen to publish gold open access, this is the point you will be asked to pay the APC (article processing charge). This varies per journal and can be found on our APC price list or on the editorial system at the point of submission. Your article will be published with a Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 user licence , which outlines how readers can reuse your work.

For UK journal article authors - if you wish to submit your work accepted by Emerald to REF 2021, you must make a ‘closed deposit’ of your accepted manuscript to your respective institutional repository upon acceptance of your article. Articles accepted for publication after 1st April 2018 should be deposited as soon as possible, but no later than three months after the acceptance date. For further information and guidance, please refer to the REF 2021 website.

All accepted authors are sent an email with a link to a licence form. This should be checked for accuracy, for example whether contact and affiliation details are up to date and your name is spelled correctly, and then returned to us electronically. If there is a reason why you can’t assign copyright to us, you should discuss this with your journal content editor. You will find their contact details on the editorial team section above.

Proofing and typesetting

Once we have received your completed licence form, the article will pass directly into the production process. We will carry out editorial checks, copyediting, and typesetting and then return proofs to you (if you are the corresponding author) for your review. This is your opportunity to correct any typographical errors, grammatical errors or incorrect author details. We can’t accept requests to rewrite texts at this stage.

When the page proofs are finalised, the fully typeset and proofed version of record is published online. This is referred to as the EarlyCite version. While an EarlyCite article has yet to be assigned to a volume or issue, it does have a digital object identifier (DOI) and is fully citable. It will be compiled into an issue according to the journal’s issue schedule, with papers being added by chronological date of publication.

How to share your paper

Visit our author rights page to find out how you can reuse and share your work.

To find tips on increasing the visibility of your published paper, read about how to promote your work .

Correcting inaccuracies in your published paper

Sometimes errors are made during the research, writing and publishing processes. When these issues arise, we have the option of withdrawing the paper or introducing a correction notice. Find out more about our article withdrawal and correction policies .

Need to make a change to the author list? See our frequently asked questions (FAQs) below.

Frequently asked questions

|

| The only time we will ever ask you for money to publish in an Emerald journal is if you have chosen to publish via the gold open access route. You will be asked to pay an APC (article-processing charge) once your paper has been accepted (unless it is a sponsored open access journal), and never at submission.

At no other time will you be asked to contribute financially towards your article’s publication, processing, or review. If you haven’t chosen gold open access and you receive an email that appears to be from Emerald, the journal, or a third party, asking you for payment to publish, please contact our support team via . |

|

| Please contact the editor for the journal, with a copy of your CV. You will find their contact details on the editorial team tab on this page. |

|

| Typically, papers are added to an issue according to their date of publication. If you would like to know in advance which issue your paper will appear in, please contact the content editor of the journal. You will find their contact details on the editorial team tab on this page. Once your paper has been published in an issue, you will be notified by email. |

|

| Please email the journal editor – you will find their contact details on the editorial team tab on this page. If you ever suspect an email you’ve received from Emerald might not be genuine, you are welcome to verify it with the content editor for the journal, whose contact details can be found on the editorial team tab on this page. |

|

| If you’ve read the aims and scope on the journal landing page and are still unsure whether your paper is suitable for the journal, please email the editor and include your paper's title and structured abstract. They will be able to advise on your manuscript’s suitability. You will find their contact details on the Editorial team tab on this page. |

|

| Authorship and the order in which the authors are listed on the paper should be agreed prior to submission. We have a right first time policy on this and no changes can be made to the list once submitted. If you have made an error in the submission process, please email the Journal Editorial Office who will look into your request – you will find their contact details on the editorial team tab on this page. |

- Lerong He State University of New York at Geneseo - USA [email protected]

- Jay J. Janney University of Dayton - USA [email protected]

Editorial Assistant

- Chunghui Kuo Individual researcher - USA [email protected]

- Chloe Campbell Emerald Publishing - UK [email protected]

Journal Editorial Office (For queries related to pre-acceptance)

- Shrushti Gupta Emerald Publishing [email protected]

Supplier Project Manager (For queries related to post-acceptance)

- Nitesh Shetty Emerald Publishing [email protected]

Editorial Advisory Board

- Steven H. Appelbaum John Molson School of Business, Concordia University - Canada

- Elisa Arrigo University of Milano-Bicocca - Italy

- Muhammad Awais Bhatti King Faisal University - Saudi Arabia

- Timothy Bartram RMIT University - Australia

- Gary Chaison Graduate School of Management, Clark University - USA

- Stewart Clegg University of Technology Sydney - Australia

- James J Cordeiro Department of Business Administration & Economics, SUNY at Brockport - USA

- Matteo Cristofaro University of Rome Tor Vegata - Italy

- J. Barton Cunningham University of Victoria - Canada

- Alison Dean Newcastle Business School - Australia

- Behnam Fahimnia University of Sydney - Australia

- Piyali Ghosh Indian Institute of Management Ranchi - India

- Anna Graziano Link Campus University - Italy

- Maria Hayu Agustini Soegijapranata Catholic University - Indonesia

- Barry Hettler Ohio University - USA

- Faizul Huq College of Business, Ohio University - USA

- Peter Jones University of Gloucestershire Business School - UK

- Boris Kabanoff School of Management, Queensland University of Technology - Australia

- Anastasia Katou University of Macedonia - Greece

- Lisa A Keister Duke University - USA

- Sascha Kraus Free University of Bozen-Bolzano - Italy

- Darren Lee-Ross James Cook University - Australia

- Frank Lefley University of Hradec Králové - Czech Republic

- Laura Meade M J Neeley School of Business, Texas Christian University - USA

- Boniface Michael California State University, Sacramento - USA

- Armando Papa University of Salerno - Italy

- R D Pathak School of Social & Economic Development, The University of South Pacific - Fiji

- Ken Peattie Cardiff University - UK

- Rajesh K. Pillania Management Development Institute, Gurgaon - India

- Abdul A. Rasheed University of Texas at Arlington - USA

- Elena Revilla Instituto de Empresa - Spain

- Hazel Rosin York University - Canada

- Kanti Saini NL Dalmia Institute of Management Studies and Research - India

- Joseph Sarkis Worcester Polytechnic Institute, USA

- Tara Shankar Shaw Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay - India

- Clive Smallman University of Western Sydney - Australia

- R P Sundarraj Indian Institute of Technology Madras - India

- Srinivas Talluri Eli Broad Graduate School of Management, Michigan State University - USA

- Vas Taras University of North Carolina at Greensboro - USA

- Greg Teal School of Management, University of Western Sydney - Australia

- Diego Vazquez-Brust University of Portsmouth, Portsmouth Business School - UK

- Karen Yuan Wang School of Management, University of Technology, Sydney - Australia

- Cherrie Jiuhua Zhu Monash University - Australia

Citation metrics

CiteScore 2023

Further information

CiteScore is a simple way of measuring the citation impact of sources, such as journals.

Calculating the CiteScore is based on the number of citations to documents (articles, reviews, conference papers, book chapters, and data papers) by a journal over four years, divided by the number of the same document types indexed in Scopus and published in those same four years.

For more information and methodology visit the Scopus definition

CiteScore Tracker 2024