The Role of Peer Pressure in Adolescents’ Risky Behaviors

- First Online: 28 August 2022

Cite this chapter

- Carlos Andrés Libisch 5 ,

- Flavio Marsiglia 6 ,

- Stephen Kulis 6 ,

- Olalla Cutrín 5 ,

- José Antonio Gómez-Fraguela 5 &

- Paul Ruiz 7

657 Accesses

1 Altmetric

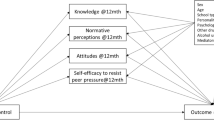

Peer pressure is defined as the subjective or actual experience of being pressured to do certain things according to certain guidelines of the peer group. Adolescence is the time when a person is most vulnerable to peer pressure. Since 2015 an international group of researchers from the USA and Uruguay have collaborated to develop a culturally adapted version of the keepin’ it REAL (kiR) substance-use prevention curriculum for implementation and testing in Uruguay. The curriculum includes a focus on socially competent ways to navigate peer pressure (Marsiglia et al., 2018 ). This chapter analyzes the peer pressure phenomenon from different theoretical and practical approaches and reports results from a randomized controlled trial of the prevention curriculum in six Uruguayan primary schools.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

The Role of Peers on School-Based Prevention Programs Targeting Adolescent Substance Use

Changing latino adolescents’ substance use norms and behaviors: the effects of synchronized youth and parent drug use prevention interventions.

Examining Potential Mechanisms of an Online Universal Prevention for Adolescent Alcohol Use: a Causal Mediation Analysis

Akers, R. L., & Jennings, W. G. (2009). The social learning theory of crime and deviance. In M. D. Krohn, A. J. Lizotte, & G. P. Hall (Eds.), Handbook on crime and deviance (pp. 103–120). Springer.

Chapter Google Scholar

Alexandrowicz, V. (2021). ESL and cultures resource . University of San Diego. Downloaded from: https://sites.sandiego.edu/esl/latin-american/

Google Scholar

Arocena, F., & Aguiar, S. (2017). Tres leyes innovadoras en Uruguay: Aborto, matrimonio homosexual y regulación de la marihuana/Three innovative laws in Uruguay: abortion, same-sex marriage and marijuana regulation. Revista de Ciencias Sociales, 30 (40), 43–62.

Bagwell, C. L. (2004). Friendships, peer networks, and antisocial behavior. In J. B. Kupersmidt & K. A. Dodge (Eds.), Children’s peer relations: From development to intervention (pp. 37–57). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10653-003

Balsa, A. I., Gandelman, N., & González, N. (2015a). Peer effects in risk aversion. Risk Analysis, 35 , 27–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/risa.12260

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Balsa, A., Gandelman, N., & Roldán, F. (2015b). Peer Effects in the Development of Capabilities in Adolescence. CAF – Working paper; 2015/09 . CAF. Retrieved from http://scioteca.caf.com/handle/123456789/820

Bernal, G., Jiménez-Chafey, M. I., & Domenech Rodríguez, M. M. (2009). Cultural adaptation of treatments: A resource for considering culture in evidence-based practice. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 40 (4), 361–368. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016401

Article Google Scholar

Beullens, K., & Vandenbosch, L. (2016). A conditional process analysis on the relationship between the use of social networking sites, attitudes, peer norms, and adolescents’ intentions to consume alcohol. Media Psychology, 19 , 310–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2015.1049275

Bonta, J., & Andrews, D. A. (2017). The psychology of criminal conduct (6th ed.). Routledge.

Botvin, G. (1990). Substance abuse prevention: Theory, practice, and effectiveness. Crime and Justice, 13 , 461–519.

Brauer, J. R., & De Coster, S. (2015). Social relationships and delinquency: Revisiting parent and peer influence during adolescence. Youth & Society, 47 , 374–394. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X12467655

Bronfenbrenner, U. (2005). The bioecological theory of human development. In U. Bronfenbrenner (Ed.), Making human beings human: Bioecological perspectives on human development (pp. 3–15). Sage Publications.

Brown, B. B., & Klute, C. (2003). Friendships, cliques, and crowds. In G. R. Adams & M. D. Berzonsky (Eds.), Blackwell handbook of adolescence (pp. 330–348). Blackwell Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470756607.ch16

Brown, B. B. (2004). Adolescents’ relationships with peers. In R. M. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology (2nd ed., pp. 363–394). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780471726746.ch12

Brown, E. C., Catalano, R. F., Fleming, C. B., Haggerty, K. P., Abbott, R. D., Cortes, R. R., & Park, J. (2005). Mediator effects in the social development model: An examination of constituent theories. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 15 , 221–235.

Brown, B. B., & Larson, J. (2009). Peer relationships in adolescence. In R. M. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology: Vol. 2. Contextual influences on adolescent development (3rd ed., pp. 74–103). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470479193.adlpsy002004

Burk, W. J., van der Vorst, H., Kerr, M., & Stattin, H. (2012). Alcohol use and friendship dynamics: Selection and socialization in early-, middle-, and late-adolescent peer networks. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 73 , 89–98. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2012.73.89

Burt, S. A. (2012). How do we optimally conceptualize the heterogeneity within antisocial behavior? An argument for aggressive versus non-aggressive behavioral dimensions. Clinical Psychology Review, 32 , 263–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2012.02.006

Burt, S. A., & Klump, K. L. (2014). Prosocial peer affiliation suppresses genetic influences on non-aggressive antisocial behaviors during childhood. Psychological Medicine, 44 , 821–830.

Choleris, E., Guo, C., Liu, H., Mainardi, M., & Valsecchi, P. (1997). The effect of demonstrator age and number on the duration of socially-induced food preferences in house mice. Behavioral Processes, 41 , 69–77.

Church, R. (1959). Emotional reactions of rats to the pain of others. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology, 52 (2), 132–134.

Cohen, L. E., & Felson, M. (1979). Social change and crime rate trends: A routine activity approach. American Sociological Review, 44 , 588–608. https://doi.org/10.2307/2094589

Collins, W. A., & Steinberg, L. (2008). Adolescent development in interpersonal context. In W. Damon & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Child and adolescent development: An advanced course (pp. 551–590). Wiley.

Couto, B., Salles, A., Sedeño, L., Peradejordi, M., Barttfeld, P., Canales-Johnson, A., Dos Santos, Y. V., Huepe, D., Bekinschtein, T., Sigman, M., Favaloro, R., Manes, F., & Ibanez, A. (2014). The man who feels two hearts: The different pathways of interoception. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 9 (9), 1253–1260.

Criss, M. M., Shaw, D. S., Moilanen, K. L., Hitchings, J. E., & Ingoldsby, E. M. (2009). Family, neighborhood, and peer characteristics as predictors of child adjustment: A longitudinal analysis of additive and mediation models. Social Development, 18 , 511–535.

Cutrín, O., Gómez-Fraguela, J. A., Maneiro, L., & Sobral, J. (2017). Effects of parenting practices through deviant peers on nonviolent and violent antisocial behaviours in middle- and late-adolescence. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 9 , 75–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpal.2017.02.001

Cutrín, O., Maneiro, L., Sobral, J., & Gómez-Fraguela, J. A. (2019). Validation of the deviant peers scale in Spanish adolescents: A new measure to assess antisocial behaviour in peers. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 41 , 185–197. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-018-9710-6

Cutrín, O., Kulis, S., Maneiro, L., MacFadden, I., Navas, M. P., Alarcón, D., Gómez-Fragüela, J. A., Villalba, C., & Marsiglia, F. F. (2020). Effectiveness of the Mantente REAL program for preventing alcohol use in Spanish adolescents. Psychosocial Intervention . https://journals.copmadrid.org/pi/art/pi2020a19

Decety, J., & Chaminade, T. (2003). Neural correlates of feeling sympathy. Neuropsychologia, 41 , 127–138.

DeLisi, M. (2015). Age-crime curve and criminal career patterns. In J. Morizot & L. Kazemian (Eds.), The development of criminal and antisocial behavior: Theory, research and practical applications (pp. 51–63). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-08720-7_4

Demanet, J., & Van Houtte, M. (2012). School belonging and school misconduct: The differing role of teacher and peer attachment. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41 (4), 499–514.

Deniz, M. (2021). Fear of missing out (FoMO) mediate relations between social self-efficacy and life satisfaction. Psicologia: Reflexão e Critica, 34 (1), 1–9. https://doi-org.proxy.timbo.org.uy/10.1186/s41155-021-00193-w

De Wall, F. (2007). Primates y filósofos. La evolución de la moral del simio al hombre . Barcelona.

Dishion, T. J., Spracklen, K. M., Andrews, D. W., & Patterson, G. R. (1996). Deviancy training in male adolescent friendships. Behavior Therapy, 27 , 373–390. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7894(96)80023-2

Dodge, K. A., Coie, J. D., & Lynam, D. (2008). Aggression and antisocial behavior in youth. In W. Damon & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Child and adolescent development: An advance course (pp. 437–472). John Wiley & Sons.

Eassey, J. M., & Buchanan, M. (2015). Fleas and feathers: The role of peers in the study of juvenile delinquency. In M. D. Krohn & J. Lane (Eds.), The handbook of juvenile delinquency and juvenile justice (pp. 199–216). John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118513217.ch14

Filardo, V. (Ed.). (2002). Tribus urbanas en Montevideo: nuevas formas de sociabilidad juvenil (1ª ed.). Editorial Trilce.

Fournier, A. K., Hall, E., Ricke, P., & Storey, B. (2013). Alcohol and the social network: Online social networking sites and college students’ perceived drinking norms. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 2 , 86–95. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032097

Fox, J., & Moreland, J. J. (2015). The dark side of social networking sites: An exploration of the relational and psychological stressors associated with Facebook use and affordances. Computers in Human Behavior, 45 , 168–176.

Gardner, T. W., Dishion, T. J., & Connell, A. M. (2008). Adolescent self-regulation as resilience: Resistance to antisocial behavior within the deviant peer context. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36 , 273–284. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-007-9176-6

Geusens, F., & Beullens, K. (2016). The association between social networking sites and alcohol abuse among Belgian adolescents: The role of attitudes and social norms. Journal of Media Psychology . https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/a000196

Geusens, F., & Beullens, K. (2017). Strategic self-presentation or authentic communication? Predicting adolescents’ alcohol references on social media. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 78 (1), 124–133. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2017.78.124 . [PubMed: 27936372].

Gonzalez-Pirelli, F., Ruiz, P. (2014). Cognición social. En: A Vasquez, Manual de Psicología Cognitiva (pp. 253–276). : Comisión Sectorial de Enseñanza.

Gottfredson, D. C., Gerstenblith, S. A., Soulé, D. A., Womer, S. C., & Lu, S. (2004). Do after school programs reduce delinquency? Prevention Science, 5 , 253–266. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:PREV.0000045359.41696.02

Granic, I., & Patterson, G. R. (2006). Toward a comprehensive model of antisocial development: A dynamic systems approach. Psychological Review, 113 , 101–131. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.113.1.101

Guzmán Facundo, F. R., Vargas Martínez, J. I., Candia Arredondo, J. S., Rodriguez Aguilar, L., & Lopez Garcia, K. S. (2019). Influencia De La Presión De Pares Y Facebook en Actitudes Favorecedoras Al Consumo De Drogas Ilícitas en Jóvenes Universitarios Mexicanos. Health & Addictions/Salud y Drogas, 19 (1), 22–30. https://doi-org.proxy.timbo.org.uy/10.21134/haaj.v19i1.399

Hatfield, E., Cacioppo, J., & Rapson, R. (1993). Emotional contagion. Current Directions in Psychological Sciences, 2 , 96–99.

Hecht, M. L., Marsiglia, F. F., Elek-Fisk, E., Wagstaff, D. A., Kulis, S., & Dustman, P. (2003). Culturally grounded substance use prevention: An evaluation of the keepin’t REAL curriculum. Prevention Science, 4 , 233–248.

Heyes, C., Jaldow, E., Nokes, T., & Dawson, G. (1994). Imitation in rats (Rattus norvegicus): The role of demonstrator action. Behavioral Processes, 32 , 173–182.

Herrenkohl, T. I., Lee, J., & Hawkins, J. D. (2012). Risk versus direct protective factors and youth violence: Seattle social development project. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 43 , S41–S56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2012.04.030

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Holleran, L. K., Reeves, L., Dustman, P., & Marsiglia, F. F. (2002). Creating culturally grounded videos for substance abuse prevention. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 2 , 55–78. https://doi.org/10.1300/J160v02n01_04

INEEd. (2020). Reporte del Mirador Educativo 6. 40 años de egreso de la educación media en Uruguay . INEEd.

Jules, M. A., Maynard, D.-M. B., & Coulson, N. (2021). Youth drug use in Barbados and England: Correlates with online peer influences. Journal of Adolescent Research , 274–310. https://doi-org.proxy.timbo.org.uy/10.1177/0743558419839226

Kreager, D. A., Rulison, K., & Moody, J. (2011). Delinquency and the structure of adolescent peer groups. Criminology, 49 , 95–127. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2010.00219.x

Kulis, S. S., Nieri, T., Yabiku, S., Stromwall, L., & Marsiglia, F. F. (2007). Promoting reduced and discontinued substance use among adolescent substance users: Effectiveness of a universal prevention program. Prevention Science, 8 , 35–49.

Kulis, S. S., Marsiglia, F. F., Porta, M., Arévalo Avalos, M. R., & Ayers, S. L. (2019). Testing the keepin’ it REAL substance use prevention curriculum among early adolescents in Guatemala City. Prevention Science, 20 , 532–543.

Kulis, S. S., García-Pérez, H. M., Marsiglia, F. F., & Ayers, S. L. (2021a). Testing a culturally adapted youth substance use prevention program in a Mexican border city: Mantente REAL. Substance Use and Misuse, 56 (2), 245–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2020.1858103

Kulis, S. S., Marsiglia, F. F., Medina-Mora, M. E., Nuño-Gutiérrez, B. L., Corona, M. D., & Ayers, S. L. (2021b). Keepin’ it REAL – Mantente REAL in Mexico: A cluster randomized controlled trial of a culturally adapted substance use prevention curriculum for early adolescents. Prevention Science, 22 (5), 645–657. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-021-01217-8

Laursen, B., Hafen, C. A., Kerr, M., & Stattin, H. (2012). Friend influence over adolescent problem behaviors as a function of relative peer acceptance: To be liked is to be emulated. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 121 , 88–94. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024707

Leander, N. P., vanDellen, M. R., Rachl-Willberger, J., Shah, J. Y., Fitzsimons, G. J., & Chartrand, T. L. (2016). Is freedom contagious? A self-regulatory model of reactance and sensitivity to deviant peers. Motivation Science, 2 , 256–267. https://doi.org/10.1037/mot0000042

Le Blanc, M. (2015). Developmental criminology: Thoughts on the past and insights for the future. In J. Morizot & L. Kazemian (Eds.), The development of criminal and antisocial behavior: Theory, research and practical applications (pp. 507–535). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-08720-7_32

Lerner, R. M. (2006). Developmental science, developmental systems, and contemporary theories of human development. In R. M. Lerner & W. Damon (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 1. Theoretical models of human development (6th ed., pp. 1–17). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470147658.chpsy0101

Magnusson, D., & Stattin, H. (2006). The person in context: A holistic-interactionistic approach. In R. M. Lerner & W. Damon (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 1. Theoretical models of human development (6th ed., pp. 400–464). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470147658.chpsy0108

Mahoney, J. L., Stattin, H., & Lord, H. (2004). Unstructured youth recreation centre participation and antisocial behaviour development: Selection influences and the moderating role of antisocial peers. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 28 , 553–560.

Malacas, C., Alfaro, P., & Hernández, R. M. (2019). Factores predictores de la intención de consumo de marihuana en adolescentes de nivel secundaria. Health and Addictions, 2 , 20–27. https://doi.org/10.21134/haaj.v20i2.481

Marsiglia, F. F., & Hecht, M. L. (2005). Keepin’it REAL: An evidence-based program . ETR Associates.

Marsiglia FF, Kulis S, Martinez Rodriguez G, Becerra D, Castillo J. (2009). Culturally specific youth substance abuse resistance skills: Applicability across the US-Mexico.

Marsiglia, F. F., & Booth, J. (2015). Cultural adaptation of interventions in real practice settings. Research on Social Work Practice, 25 , 423–432.

Marsiglia, F. F., Kulis, S., Booth, J. M., Nuño-Gutiérrez, B. L., & Robbins, D. E. (2015). Long-term effects of the keepin’it REAL model program in Mexico: Substance use trajectories of Guadalajara middle school students. Journal of Primary Prevention, 36 , 93–104.

Marsiglia, F. F., Kulis, S., Kiehne, E., Ayers, E., Libisch Recalde, C., & Barros Sulca, L. (2018). Adolescent substance use prevention and legalization of Marijuana in Uruguay: A feasibility trial of the keepin’ it REAL prevention program. Journal of Substance Use, 23, 457-465. Border. Research on Social Work Practice, 19 (2), 152–164.

Marsiglia, F. F., Medina-Mora, M. E., Gonzalvez, A., Alderson, G., Harthun, M., Ayers, S., Nuño Gutiérrez, B., Corona, M. D., Mendoza Melendez, M. A., & Kulis, S. (2019). Binational cultural adaptation of the keepin’ it REAL substance use prevention program for adolescents in Mexico. Prevention Science, 20 , 1125–1135.

McFarland, L. A., & Ployhart, R. E. (2015). Social media: A contextual framework to guide research and practice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100 , 1653–1677. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039244

McGloin, J. M. (2009). Delinquency balance: Revisiting peer influence. Criminology, 47 , 439–477. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2009.00146.x

Meldrum, R. C., & Barnes, J. C. (2017). Unstructured socializing with peers and delinquent behavior: A genetically informed analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46 , 1968–1981.

Melgar, A. K., Reynés, M. D., & Paredes-Labra, J. (2017). Plan CEIBAL e inclusión social. Un caso paradigmático/Plan CEIBAL and social inclusion. A paradigmatic case./Plano CEIBAL e inclusão social. Um caso paradigmático. Psicología, Conocimiento y Sociedad, 7 (2), 45–63. https://doi-org.proxy.timbo.org.uy/10.26864/pcs.v7.n2.4

Moffitt, T. E. (2018). Male antisocial behavior in adolescence and beyond. Nature Human Behavior, 2 , 177–186. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-018-0309-4

Monahan, K. C., Rhew, I. C., Hawkins, J. D., & Brown, E. C. (2014). Adolescent pathways to co-occurring problem behavior: The effects of peer delinquency and peer substance use. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 24 , 630–645. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12053

Nagoshi, J. L., Kulis, S., Marsiglia, F. F., & Piña-Watson, B. (2020). Accounting for linguistic acculturation, coping, antisociality and depressive affect in the gender role-alcohol use relationship in Mexican American adolescents: A moderated mediation model for boys and girls. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332640.2020.1781732

Nakahashi, W., & Ohtsuki, H. (2017). Evolution of emotional contagion in group-living animals. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 15 (440), 12–20.

Nesi, J., Rothenberg, W. A., Hussong, A. M., & Jackson, K. M. (2017). Friends’ alcohol-related social networking site activity predicts escalations in adolescent drinking: Mediation by peer norms. Journal of Adolescent Health, 60 , 641–647. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.01.009

Nesi, J., Choukas-Bradley, S., & Prinstein, M. J. (2018). Transformation of adolescent peer relations in the social media context: Part 2-application to peer group processes and future directions for research. Clinical Child & Family Psychology Review, 21 (3), 295–319. https://doi-org.proxy.timbo.org.uy/10.1007/s10567-018-0262-9

Nicol, C. (1995). The social transmission of information and behavior. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 44 , 79–98.

Niland, P., Lyons, A. C., Goodwin, I., & Hutton, F. (2015). Friendship work on Facebook: Young adults’ understandings and practices of friendship. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 25 (2), 123–137.

Nummenmaa, L., Hirvonen, J., Parkkola, R., & Hietanen, J. (2008). Is emotional contagion special? An fMRI study on neural systems for affective and cognitive empathy. NeuroImage, 43 , 571–580.

Osgood, D. W., Wilson, J. K., O’Malley, P. M., Bachman, J. G., & Johnston, L. D. (1996). Routine activities and individual deviant behavior. American Sociological Review, 61 , 635–655. https://doi.org/10.2307/2096397

Palardy, G. J. (2013). High school socioeconomic segregation and student attainment. American Educational Research Journal, 50 (4), 714–754. https://doi-org.proxy.timbo.org.uy/10.2307/23526103

Patterson, G. R., & Yoerger, K. (1999). Intraindividual growth in covert antisocial behaviour: A necessary precursor to chronic juvenile and adult arrests? Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 9 , 24–38. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbm.289

Pérez, A., & Mejía, J. (2015). Evolución de la prevención del consumo de drogas en el mundo y en américa latina . Corporación Nuevos Rumbos. ISBN: 978-958-57904-21.

Peter, J., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2013). The effects of internet communication on adolescents’ psychosocial development: An assessment of risks and opportunities. In E. Scharrer (Ed.), The international encyclopedia of media studies, volume 5: Media effects/media psychology (pp. 678–697). Wiley-Blackwell.

Pilatti, A., Brussino, S. A., & Godoy, J. C. (2013). Factores que influyen en el consumo de alcohol de adolescentes argentinos: un path análisis prospectivo. Revista de Psicología, 22 , 22–36. https://doi.org/10.5354/0719-0581.2013.27716

Reeves, L., Dustman, P., Holleran, L., & Marsiglia, F. F. (2008). Creating culturally grounded prevention videos: Defining moments in the journey to collaboration. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 8 , 65–94.

Rubin, K. H., Bukowski, W. M., Parker, J. G., & Bowker, J. C. (2008). Peer interactions, relationships, and groups. In W. Damon & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Child and adolescent development: An advanced course (pp. 141–180). John Wiley & Sons.

Ruiz, P. (2015). ¿Qué sabemos sobre el contagio emocional?. Definición, evolución, neurobiología y su relación con la psicoterapia. Cuadernos de Neuropsicología, 9 (3), 15–24.

Ruiz, P., Calliari, A., & Pautassi, R. (2018). Reserpine-induced depression is associated in female, but not in male, adolescent rats with heightened, fluoxetine-sensitive, ethanol consumption. Behavioral Brain Research, 21 (348), 160–170.

Ruiz, P. (2019). Estudio de variables cognitivas, neuroendócrinas y consumo de alcohol en modelos animales de trastornos de estados de ánimo, y su contraparte en humanos (Tesis de Doctorado no publicada) . Universidad Nacional de Córdoba.

Sanchez, C., Andrade, P., Bentancourt, D., & Vital, G. (2013). Escala de Resistencia a la presión de los amigos para el consumo de alcohol. Actas de Investigación Psicológica, 3 (1), 917–929.

Sancassiani, F., Pintus, E., Holte, A., Paulus, P., Moro, M. F., Cossu, G., & Lindert, J. (2015). Enhancing the emotional and social skills of the youth to promote their wellbeing and positive development: A systematic review of universal school-based randomized controlled trials. Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health, 11 (Suppl 1 M2), 21. https://doi.org/10.2174/1745017901511010021

Scheier, L. M. (2012). Primary prevention models: The essence of drug abuse prevention in schools. In H. Shaffer, D. A. LaPlante, & S. E. Nelson (Eds.), APA addiction syndrome handbook ( Recovery, prevention, and other issues ) (Vol. 2, pp. 197–223). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/13750-009

Snyder, J. J., Schrepferman, L. P., Bullard, L., McEachern, A. D., & Patterson, G. R. (2012). Covert antisocial behavior, peer deviancy training, parenting processes, and sex-differences in the development of antisocial behavior during childhood. Development and Psychopathology, 24 , 1117–1138. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579412000570

Steinberg, L. (2017). Adolescence (11th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.

Subrahmanyam, K., & Šmahel, D. (2011). Digital youth: The role of media in development . Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-6278-2

Book Google Scholar

Sutherland, E. H. (1972). The theory of differential association. In D. Dressler (Ed.), Readings in criminology and penology (pp. 365–371). Columbia University Press. https://doi.org/10.7312/dres92534-039

Tanner-Smith, E. E., Durlak, J. A., & Marx, R. A. (2018). Empirically based mean effect size distributions for universal prevention programs targeting school-aged youth: A review of meta-analyses. Prevention Science, 19 , 1091–1101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-018-0942-1

Thurow, C. F., Junior, E. L. P., Westphal, R., de São Tiago, F. M. L., & Schneider, D. R. (2020). Risk and protective factors for drug use: A scoping review on the communities that care youth survey. International Journal of Advanced Engineering Research and Science (IJAERS), 7 . https://doi.org/10.22161/ijaers.711.5

Tompsett, C. J., Domoff, S. E., & Toro, P. A. (2013). Peer substance use and homelessness predicting substance abuse from adolescence through early adulthood. American Journal of Community Psychology, 51 , 520–529. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-013-9569-3

Zentall, T., & Levine, J. (1972). Observational learning and social facilitation in the rat. Science, 178 , 1220–1221.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Universidade de Santiago de Compostela, Santiago de Compostela, Spain

Carlos Andrés Libisch, Olalla Cutrín & José Antonio Gómez-Fraguela

Arizona State University, Tempe, FL, USA

Flavio Marsiglia & Stephen Kulis

Universidad de la República, Facultad de Psicología, Montevideo, Uruguay

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Carlos Andrés Libisch .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Sociocognitive Neuropsychology Laboratory (LINES), Salvador, Bahia, Brazil

Marcus Vinicius Alves

Universidade Estadual do Norte do Paraná, Bandeirantes, Paraná, Brazil

Roberta Ekuni

Universidad Nacional de Hurlingham, Buenos Aires, Argentina

Maria Julia Hermida

University of the Republic, Montevideo, Uruguay

Juan Valle-Lisboa

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Libisch, C.A., Marsiglia, F., Kulis, S., Cutrín, O., Gómez-Fraguela, J.A., Ruiz, P. (2022). The Role of Peer Pressure in Adolescents’ Risky Behaviors. In: Alves, M.V., Ekuni, R., Hermida, M.J., Valle-Lisboa, J. (eds) Cognitive Sciences and Education in Non-WEIRD Populations. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-06908-6_8

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-06908-6_8

Published : 28 August 2022

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-06907-9

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-06908-6

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Behavioral Science and Psychology (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- DOI: 10.2991/assehr.k.220704.079

- Corpus ID: 250661200

A Survey of the Causes and Effects of Peer Pressure in College Students

- Published in Proceedings of the 3rd… 2022

- Education, Psychology

- Proceedings of the 2022 3rd International Conference on Mental Health, Education and Human Development (MHEHD 2022)

Figures from this paper

10 References

Related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Peer Influences on Adolescent Decision Making

Dustin albert.

Duke University

Jason Chein

Temple University

Laurence Steinberg

Research efforts to account for elevated risk behavior among adolescents have arrived at an exciting new stage. Moving beyond laboratory studies of age differences in “cool” cognitive processes related to risk perception and reasoning, new approaches have shifted focus to the influence of social and emotional factors on adolescent neurocognition. We review recent research suggesting that adolescent risk-taking propensity derives in part from a maturational gap between early adolescent remodeling of the brain's socio-emotional reward system and a gradual, prolonged strengthening of the cognitive control system. At a time when adolescents spend an increasing amount of time with their peers, research suggests that peer-related stimuli may sensitize the reward system to respond to the reward value of risky behavior. As the cognitive control system gradually matures over the course of the teenage years, adolescents grow in their capacity to coordinate affect and cognition, and to exercise self-regulation even in emotionally arousing situations. These capacities are reflected in gradual growth in the capacity to resist peer influence.

“…it seems like people accept you more if you're, like, a dangerous driver or something. If there is a line of cars going down the road and the other lane is clear and you pass eight cars at once, everybody likes that. […] If my friends are with me in the car, or if there are a lot of people in the line, I would do it, but if I'm by myself and I didn't know anybody then I wouldn't do it. That's no fun.'” Anonymous teenager, as reported in The Culture of Adolescent Risk-Taking ( Lightfoot, 1997 ; p.10)

It is well-established that adolescents are more likely than children or adults to take risks, as evinced by elevated rates of experimentation with alcohol, tobacco, and drugs, unprotected sexual activity, violent and nonviolent crime, and reckless driving ( Steinberg, 2008 ). Early research efforts to identify the distinguishing cognitive immaturity underlying adolescents' heightened risk-taking propensity bore little fruit. A litany of carefully-controlled laboratory experiments contrasted adolescent and adult capacities to perceive and process fundamental components of risk information, but found that adolescents possess the knowledge, values, and processing efficiency to evaluate risky decisions as competently as adults ( Reyna & Farley, 2006 ).

If adolescents are so risky in the real world, why do they appear so risk-averse in the lab? We propose that the answer to this question is nicely illustrated by the American teenager quoted above: “ …if I'm by myself and I didn't know anybody then I wouldn't do it. That's no fun .” If adolescents made all of their decisions involving drinking, driving, dalliances, and delinquency in the cool isolation of an experimenter's testing room, those decisions would likely appear as risk-averse as those of adults. But therein lies the rub: teenagers spend a remarkable amount of time in the company of other teenagers. This paper describes a new wave of research on the neurobehavioral substrates of adolescent decision making in peer contexts suggesting that the company of other teenagers fundamentally alters the calculus of adolescent risk taking.

Peer Influences on Adolescent Risk Behavior

Consistent with self-reports of lower resistance to peer influence among adolescents than adults ( Steinberg & Monahan, 2007 ), observational data point to the role of peer influences as a primary contextual factor contributing to adolescents' heightened tendency to make risky decisions. For instance, crime statistics indicate that adolescents typically commit delinquent acts in peer groups, whereas adults more frequently offend alone ( Zimring, 1998 ). Furthermore, one of the strongest predictors of delinquent behavior in adolescence is affiliation with delinquent peers, an association that has been attributed in varying proportions to peer socialization (e.g., “deviancy training”; Dishion, Bullock, & Granic, 2002 ) and friendship choices, wherein risk-taking adolescents naturally gravitate toward one another (e.g., Bauman & Ennett, 1996 ). Given the difficulty of distinguishing between these causal alternatives with correlational data, our lab has pursued a program of experimental research directly comparing the behavior of adolescents and adults when making decisions either alone, or in the presence of their peers.

In the first experimental study to examine age differences in the effect of peer context on risky decision making ( Gardner & Steinberg, 2005 ), early adolescents (mean age = 14), late adolescents (mean age = 19), and adults (mean age = 37) were tested on a computerized driving task, called the “Chicken Game,” which challenges the driver to advance a vehicle as far as possible on the driving course, while avoiding a crash into a wall that could appear, without warning, at any point on the course. Peer context was manipulated by randomly assigning each group of three participants to play the game either individually (alone in the room), or with two same-aged peers in the room. When tested alone, the participants from each of the three age groups engaged in a comparable amount of risk taking. In contrast, early adolescents scored twice as high on an index of risky driving when tested with their peers in the room than when alone, whereas late adolescents were approximately 50% riskier in groups, and adults showed no difference in risky driving related to social context. The ongoing goal of our research program is to further specify the behavioral and neural mechanisms of this peer effect on adolescent risk taking.

A Neurodevelopmental Model of Peer Influences on Adolescent Decision Making

Building on extensive evidence demonstrating maturational changes in brain structure and function occurring across the second decade of life (and frequently beyond), we have advanced a neurodevelopmental account of heightened susceptibility to peer influence among adolescents ( Steinberg, 2008 ; Albert & Steinberg, 2011 ). In brief, we propose that, among adolescents more than adults, the presence of peers “primes” a reward-sensitive motivational state that increases the subjective value of immediately available rewards and thereby increases the probability that adolescents will favor the short-term benefits of a risky choice over the long-term value of a safe alternative. Although a comprehensive presentation of the behavioral and neuroscientific evidence underlying this hypothesis is beyond our current scope (but see Albert & Steinberg, 2011 ), a brief review of three fundamental assumptions of this model will set the stage for a description of our peer influence studies.

First, decisions are a product of both cognitive and affective input, even when affect is unrelated to the choices under evaluation

Research based on adult populations has identified several pathways by which affect influences decision making ( Loewenstein, Weber, Hsee, & Welch, 2001 ). For instance, the anticipated emotional outcome of a behavioral option -- how one expects to feel after making a given choice --contributes to one's cognitive assessment of its expected value. Indeed, affective states may influence decision processing even when the source of the affect is not directly related to the choices under evaluation. Such incidental affective influences are apparent in experiments demonstrating the effect of pre-existing or experimentally elicited affective states on adult perception, memory, judgment, and behavior ( Winkielman, Knutson, Paulus, & Trujillo, 2007 ). One experiment illustrating this effect found that elicitation of incidental positive emotion (via presentation of masked happy faces) caused participants to pour and drink more of a novel beverage than participants who had viewed angry faces, despite no differences in self-reported emotion between the two groups ( Winkielman, Berridge, & Wilbarger, 2005 ). Consistent with evidence for extensive overlap in the neural circuitries implicated in the evaluation of socio-emotional and choice-related incentive cues (e.g., ventral striatum, ventromedial prefrontal cortex; for a recent review, see Falk, Way, & Jasinska, 2012 ), Winkielman and colleagues describe this priming effect as an instance of approach sensitization . That is, neural responses to positively valenced socio-emotional stimuli – in this case, responses not even reaching the level of conscious awareness – may sensitize approach (i.e., “GO”) responding to unrelated incentive cues. As we describe below, several characteristics of adolescent neurobehavioral functioning suggest that this approach sensitization effect could be a particularly powerful influence on adolescent decision making in peer contexts.

Second, adolescents exhibit stronger “bottom-up” affective reactivity than adults in response to socially relevant stimuli

Whereas some controversy remains regarding the degree to which adolescents are more or less sensitive than children and adults to non-social reward cues ( Galvan, 2010 ; Spear, 2009 ), few scholars now dispute that adolescence is a period of peak neurobehavioral sensitivity to social stimuli ( Burnett, Sebastian, Kadosh, & Blakemore, 2011 ; Somerville, this issue ). Puberty-related increases in gonadal hormones have been linked to a proliferation of receptors for oxytocin within subcortical and limbic circuits, including the amygdala and striatum ( Spear, 2009 ). Oxytocin neurotransmission has been implicated in a variety of social behaviors, including facilitation of social bonding and recognition and memory for positive social stimuli (Insel & Fernald, 2004). Alongside concurrent changes in dopaminergic function within neural circuits broadly implicated in incentive processing ( Spear, 2009 ), these puberty-related increases in gonadal hormones and oxytocin receptor density contribute to changes in a constellation of social behaviors observed in adolescence.

Peer relations are never more salient than in adolescence. In addition to a puberty-related spike in interest in opposite-sex relationships, adolescents spend more time than children or adults interacting with peers, report the highest degree of happiness when in peer contexts, and assign greatest priority to peer norms for behavior ( Brown & Larson, 2009 ). This developmental peak in affiliation motivation appears highly conserved across species: Adolescent rats also spend more time than younger or older rats interacting with peers, while showing evidence that such interactions are highly rewarding ( Doremus-Fitzwater, Varlinskaya, & Spear, 2010 ). Moreover, several developmental neuroimaging studies indicate that, relative to children and adults, adolescents show heightened neural activation in response to a variety of social stimuli, such as facial expressions and social feedback ( Burnett et al., 2011 ). For instance, one of the first longitudinal neuroimaging studies of early adolescence demonstrated a significant increase from ages 10 to 13 in ventral striatal and ventral prefrontal reactivity to facial stimuli ( Pfeifer et al., 2011 ). Together, this evidence for hypersensitivity to social stimuli suggests that adolescents may be more likely than adults to generate a baseline state of heightened approach motivation when exposed to positively valenced peer stimuli in a decision-making scenario, thus setting the stage for an exaggerated approach sensitization effect of peer context on risky decision making.

Third, adolescents are less capable than adults of “top-down” cognitive control of impulsive behavior

In contrast to the relatively sudden changes in social processing that occur around the time of puberty, cognitive capacities supporting efficient self-regulation mature in a gradual, linear pattern over the course of adolescence. In developmental parallel with structural brain changes thought to support neural processing efficiency (e.g., increased axonal myelination), adolescents show continued gains in response inhibition, planned problem solving, flexible rule use, impulse control, and future orientation ( Steinberg, 2008 ). Indeed, evidence is growing for a direct link between structural and functional brain maturation during adolescence and concurrent improvements in cognitive control. In addition to studies correlating white matter maturation with age-related cognitive improvements ( Schmithorst & Yuan, 2010 ), developmental neuroimaging studies utilizing tasks requiring response inhibition (e.g., Go-No/Go, Stroop, flanker tasks, ocular antisaccade) describe relatively inefficient recruitment by adolescents of the core neural circuitry supporting cognitive control (e.g., lateral prefrontal and anterior cingulate cortex) ( Luna, Padmanabhan, & O'Hearn, 2010 ). Moreover, research on age differences in control-related network dynamics demonstrate adolescent immaturity in the functional integration of neural signals deriving from specialized cortical and subcortical “hub” regions ( Stevens, 2009 ). This immature capacity for functional integration may contribute to adolescent difficulties in simultaneously evaluating social, affective, and cognitive factors relevant to a given decision, particularly when social and emotional considerations are disproportionately salient.

Identification of Mechanisms Underlying Peer Influences on Adolescent Decision Making

In an effort to further specify the neurodevelopmental vulnerability underlying adolescent susceptibility to peer influence, we have conducted a series of behavioral and neuroimaging experiments comparing adolescent and adult decision making in variable social contexts. Specifically, we have sought to determine whether the presence of peers biases adolescent decision making by (a) modulating responses to incentive cues, consistent with the approach sensitization hypothesis, (b) disrupting inhibitory control, or (c) altering both of these processes. As a first step in addressing this question, we conducted an experiment that randomly assigned late adolescents (ages 18 and 19) to complete a series of tasks either alone or in the presence of two same-age, same-sex peers. Risk-taking propensity was assessed using the “Stoplight” game, a first-person driving game wherein participants must advance through a series of intersections to reach a finish line as quickly as possible to receive a monetary reward ( Figure 1 ). Each intersection is marked by a stoplight that turns yellow (and sometimes red) as the car approaches, and participants must decide to either “hit the brakes” (and lose time while waiting for the light to turn green) or run the light (and risk crashing while crossing through an intersection). We also administered tasks for cognitive control (Go/No-Go) and preference for immediate-over-delayed rewards (Delay Discounting). Whereas no group differences were evident on the Go/No-Go index of inhibitory control, adolescents in the peer presence condition took more risks on the Stoplight task ( Albert et al., 2009 ) and indicated stronger preference for immediate-over-delayed rewards ( O'Brien, Albert, Chein, & Steinberg, 2011 ), relative to adolescents who completed the tasks alone.

In the Stoplight driving game, participants are instructed to attempt to reach the end of a straight track as quickly as possible. At each of 20 intersections, participants render a decision to either stop the vehicle (STOP) or to take a risk and run the traffic light (GO). Stops result in a short delay. Successful risk taking results in no delay. Unsuccessful risk taking results in a crash, and a relatively long delay. Summary indices of risk taking include (a) the proportion of intersections in which the participant decides to run the light, and (b) the total number of crashes.

Findings from a recent follow-up experiment suggest that peer observation influences adolescents' decision making even when the peer is anonymous and not physically present in the same room. Utilizing a counterbalanced, repeated-measures design, we assessed the task performance of late adolescents once in a standard “alone” condition, and once in a deception condition that elicited the impression that their task performance was being observed by a same-age peer in an adjoining room. As predicted, participants exhibited stronger preference for immediate rewards on a delay discounting task when they believed they were being observed, relative to alone ( Weigard, Chein, & Steinberg, 2011 ). Peer observation also resulted in a higher rate of monetary gambles on a probabilistic gambling task, but only for participants with relatively lower self-reported resistance to peer influence ( Smith, Chein, & Steinberg, 2011 ). Along similar lines, Segalowitz et al. (2012) report that individuals high in self-reported sensation seeking are especially susceptible to the peer effect on risk taking. Considered together, these behavioral results suggest that peer presence increases adolescents' risk taking by increasing the salience (or subjective value) of immediately available rewards, and that some adolescents are more susceptible to this effect than others.

Our recent work has utilized brain imaging to more directly examine the neural dynamics underlying adolescent susceptibility to peer influences. In the first of these studies, we scanned adolescents and adults while they played the Stoplight game, again utilizing a counterbalanced within-subjects design ( Chein, Albert, O'Brien, Uckert, & Steinberg, 2011 ). All subjects played the game in the scanner twice -- once in a standard “alone” condition, and once in a “peer” condition, wherein they were made aware that their performance was being observed on a monitor in a nearby room by two same-age, same-sex peers who had accompanied them to the experiment. As predicted, adolescents but not adults took significantly more risks when observed by peers than when alone ( Figure 2 ). Furthermore, analysis of neural activity during the decision-making epoch showed greater activation of brain structures implicated in reward valuation (ventral striatum and orbitofrontal cortex) for adolescents in the peer relative to the alone scans, an effect that was not apparent for adults ( Figure 3 ). Indeed, the degree to which participants (across all ages) evinced peer-greater-than- alone activation in the ventral striatum was inversely correlated with self-reported resistance to peer influence ( Figure 4 ). This study represents the first evidence that peer presence accentuates risky decision making in adolescence by modulating activity in the brain's reward valuation system.

Mean (a) percentage of risky decisions and (b) number of crashes for adolescent, young adult, and adult participants when playing the Stoplight driving game either alone or with a peer audience. Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean.

(a) Brain regions exhibiting an age by social condition interaction included the right ventral striatum (VS, MNI peak coordinates: x = 9, y = 12, z = -8) and left orgitofrontal cortex (OFC, MNI peak coordinates: x = -22, y = 47, z = -10). (b) Mean estimated BOLD signal change (beta coefficient) from the four peak voxels of the VS and the OFC in adolescents (adols.), young adults (YA), and adults under ALONE and PEER conditions. Error bars indicate standard errors of the mean. Brain images are shown by radiological convention (left on right), and thresholded at p < .01 for presentation purposes.

Resistance to Peer Influence correlated with Stoplight-related activity in the right ventral striatum (VS). Estimated activity was extracted from an average of the four peak voxels in the VS region of interest. Scatterplot of activity in the VS indicating an inverse linear correlation between self-reported resistance to peer influence (RPI) and the neural peer effect (i.e., the difference in average VS activity in peer relative to alone conditions, or βpeer − βalone).

Conclusions and Future Directions

Although our work to date has indicated that the effect of peers on adolescent risk taking is mediated by changes in reward processing, we recognize that the distinction between risk taking that is attributable to heightened arousal of the brain's reward system versus that which is due to immaturity of the cognitive control system is somewhat artificial, since these brain systems influence each other in a dynamic fashion. Consistent with this notion, in a comparison of children, adolescents, and adults on a task that requires participants to either produce or inhibit a motor response to pictures of calm or happy faces, Somerville, Hare, and Casey (2011) not only found elevated ventral striatal activity for adolescents in response to happy faces, which the authors discuss as an “appetitive” cue, but also a corresponding increase in failures to inhibit motor responses to the happy relative to the calm facial stimuli. Thus, adolescents' exaggerated response to positively-valenced social cues is shown here to directly undermine their capacity to inhibit approach behavior. Translated to the peer context, this finding suggests that adolescents may not only be particularly sensitive to the reward-sensitizing effects of social stimuli, but that this sensitization may further undermine their capacity to “put the brakes on” impulsive responding.

Despite the promise of this conceptual model, further work is needed to specify the neurodevelopmental dynamics underlying adolescent susceptibility to peer influence, and to translate this understanding to the design of effective prevention programs. In an effort to “decompose” the peer effect, we are currently examining age differences in the influence of social cues on neural activity underlying performance on tasks specifically tapping reward processing and response inhibition. In addition, we are investigating whether conditions known to diminish cognitive control (e.g., alcohol intoxication) might exacerbate the influence of peer context on risky decision making. Finally, as a first step toward our ultimate goal of utilizing this research to improve the efficacy of risk-taking prevention programs, we are examining whether targeted training designed to promote earlier maturation of cognitive control skills might attenuate the influence of peers on adolescent decision making.

Contributor Information

Dustin Albert, Duke University.

Jason Chein, Temple University.

Laurence Steinberg, Temple University.

Recommended Readings

- Albert D, Steinberg L. A comprehensive presentation of the neurodevelopmental model of peer influences on adolescent decision making 2011 See References. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Burnett S, Sebastian C, Kadosh K, Blakemore An up-to date review of the social neuroscience of adolescence 2011 See References. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chein J, Albert D, O'Brien L, Uckert K, Steinberg L. An empirical report of peer influences on adolescent risk taking and neural activity 2011 See References. [ Google Scholar ]

- Falk EG, Way BM, Jasinska AJ. A recent review highlighting promising new directions for neuroscientific research on social influence across the lifespan 2012 See References. [ Google Scholar ]

- Spear LP. A thorough and accessible textbook survey of neuroscientific research on adolescent development 2009 See References. [ Google Scholar ]

- Albert D, O'Brien L, DiSorbo A, Uckert K, Egan DE, Chein J, Steinberg L. Peer influences on risk taking in young adulthood; Poster session presented at the biennial meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development; Denver, CO. 2009. Apr, [ Google Scholar ]

- Albert D, Steinberg L. Peer influences on adolescent risk behavior. In: Bardo MT, Fishbein DH, Milich &R, editors. Inhibitory Control and Drug Abuse Prevention: From Research to Translation. New York: Springer; 2011. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bauman KE, Ennett SE. On the importance of peer influence for adolescent drug use: Commonly neglected considerations. Addiction. 1996; 91 :185–198. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brown BB, Larson J. Handbook of adolescent psychology, Vol 2: Contextual influences on adolescent development. 3rd. Hoboken, NJ US: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2009. Peer relationships in adolescents; pp. 74–103. [ Google Scholar ]

- Burnett S, Sebastian C, Kadosh K, Blakemore The social brain in adolescence: Evidence from functional magnetic resonance imaging and behavioural studies. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2011; 35 :1654–1664. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chein J, Albert D, O'Brien L, Uckert K, Steinberg L. Peers increase adolescent risk taking by enhancing activity in the brain's reward circuitry. Developmental Science. 2011; 14 :F1–F10. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dishion TJ, Bullock BM, Granic I. Pragmatism in modeling peer influence: Dynamics, outcomes, and change processes. Development and Psychopathology. 2002; 14 (4):969–981. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Doremus-Fitzwater TL, Varlinskaya EI, Spear LP. Motivational systems in adolescence: possible implications for age differences in substance abuse and other risk-taking behaviors. Brain and cognition. 2010; 72 :114–23. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Falk EG, Way BM, Jasinska AJ. An imaging genetics approach to understanding social influence. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2012; 6 :1–13. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Galvan A. Adolescent development of the reward system. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2010; 4 :1–9. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gardner M, Steinberg L. Peer influence on risk taking, risk preference, and risky decision making in adolescence and adulthood: An experimental study. Developmental Psychology. 2005; 41 :625–635. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lightfoot C. The culture of adolescent risk-taking. New York: Guilford Press; 1997. [ Google Scholar ]

- Loewenstein G, Weber EU, Hsee CK, Welch N. Risk as feelings. Psychological Bulletin. 2001; 127 :267–286. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Luna B, Padmanabhan A, O'Hearn K. What has fMRI told us about the development of cognitive control through adolescence? Brain and Cognition. 2010; 72 :101–113. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- O'Brien L, Albert D, Chein J, Steinberg L. Adolescents prefer more immediate rewards when in the presence of their peers. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2011; 21 :747–753. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pfeifer JH, Masten CL, Moore WE, Oswald TM, Iacoboni M, Mazziotta JC, Dapretto M. Entering adolescence: Resistance to peer influence, risky behavior, and neural changes in emotional reactivity. Neuron. 2011; 69 :1029–1036. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Reyna VF, Farley F. Risk and rationality in adolescent decision making - Implications for theory, practice, and public policy. Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 2006; 7 :1–44. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schmithorst VJ, Yuan WH. White matter development during adolescence as shown by diffusion MRI. Brain and Cognition. 2010; 72 :16–25. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Segalowitz SJ, Santesso DL, Willoughby T, Reker DL, Campbell K, Chalmers H, Rose-Krasnor L. Adolescent peer interaction and trait surgency weaken medial prefrontal cortex responses to failure. Social, Cognitive, and Affective Neuroscience. 2012; 7 :115–124. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Smith A, Chein J, Steinberg L. Developmental differences in reward processing in the presence of peers; Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Neuroscience; Washington. 2011. Nov, [ Google Scholar ]

- Somerville LH. this issue [ Google Scholar ]

- Somerville LH, Hare TA, Casey BJ. Frontostriatal maturation predicts cognitive control failure to appetitive cues in adolescents. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2011; 23 :2123–2134. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Spear LP. The behavioral neuroscience of adolescence. New York: W. W. Norton; 2009. [ Google Scholar ]

- Steinberg L. A social neuroscience perspective on adolescent risk-taking. Developmental Review. 2008; 28 :78–106. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Steinberg L, Monahan KC. Age differences in resistance to peer influence. Developmental Psychology. 2007; 43 :1531–1543. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stevens MC. The developmental cognitive neuroscience of functional connectivity. Brain and Cognition. 2009; 70 :1–12. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Weigard A, Chein J, Steinberg L. Influence of anonymous peers on risk-taking behavior in adolescents; Paper presented at the Eleventh Annual Stanford Undergraduate Psychology Conference; Stanford, CA. 2011. May, [ Google Scholar ]

- Winkielman P, Berridge KC, Wilbarger JL. Unconscious affective reactions to masked happy versus angry faces influence consumption behavior and judgments of value. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2005; 31 :121–135. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Winkielman P, Knutson B, Paulus MP, Trujillo JL. Affective influence on judgments and decisions: Moving towards core mechanisms. Review of General Psychology. 2007; 11 :179–192. [ Google Scholar ]

- Zimring F. American Youth Violence Studies in Crime and Public Policy. New York: Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1998. [ Google Scholar ]

IMAGES

COMMENTS

PDF | On Jan 12, 2019, Vangie M. Moldes and others published Students, Peer Pressure and their Academic Performance in School | Find, read and cite all the research you need on ResearchGate

When effort is observable to peers, students may try to avoid social penalties by conforming to prevailing norms. To test this hypothesis, we first consider a natural experiment that introduced a performance leaderboard into computer-based high school courses. The result was a 24 percent performance decline. The decline appears to be driven by ...

Research on digital peer pressure highlights the need for innovative interventions addressing online ethical dilemmas and promoting digital citizenship (Lenhart et al., 2020). Interventions and Prevention Strategies Efforts to mitigate the adverse effects of peer pressure have led to the development of various intervention

The alterations wrought by peer influence can be for good or for ill. Peer influence is a neutral term, agnostic to the type of change. In this sense, peer influence stands apart from peer pressure and socialization, which describe (respectively) maladaptive and adaptive change (Laursen, 2018). Peer pressure has negative connotations that imply ...

Abstract: Peer pressure is influential in swaying adolescents' actions and decisions. To. investigate the holistic influence of peer pressure on adolescence, this paper conducts. literature ...

Peer pressure has long been recognized as a significant influence on individuals' behaviors, particularly in adolescence and young adulthood. This paper provides a detailed review of the literature over the past two decades on the peer pressure. Peer pressure remains a pervasive influence on individuals' behaviors, particularly during adolescence and emerging adulthood. Drawing upon a diverse ...

Complementing previous research on peer pressure where sources of peer pressure were statically unearthed in and out of the field of web-based learning (e.g., Chang et al., 2014; Vanderhoven et al., 2015), this study also contributes to a detailed and dynamic understanding of the features of peer pressure triggers, especially in the WPL setting.

Working Paper 20714. DOI 10.3386/w20714. Issue Date November 2014. When effort is observable to peers, students may act to avoid social penalties by conforming to prevailing norms. To test for such behavior, we conducted an experiment in which 11th grade students were offered complimentary access to an online SAT preparatory course.

8 Identifying this as the effect of peer pressure or social concerns requires that information is to an extent localized, i.e., that the choices a student taking some honors classes makes in their honors class does not get fully revealed to their non-honors peers, or vice-versa. We discuss this in more detail below.

Peer pressure takes place in person and in online social interactions. Social media is a unique social context that influences individuals' thoughts, behaviors, and relationships (McFarland & Ployhart, 2015; Peter & Valkenburg, 2013; Subrahmanyam & Šmahel, 2011).Research has shown that peer influence processes on social media contribute to adolescents' risky behaviors, especially alcohol use.

Peer pressure refers to the psychological pressure generated by people of similar age and status comparing with each other, thus promoting changes in individual thoughts and behaviors. Peer pressure, as a common pressure in the lives of college students, has profoundly affected the studies and lives of college students. Therefore, it is of great significance to correctly recognize and deal ...

surrounding negative peer influence, they are more likely to prevent it and be more adequately prepared to help a teenager facing negative aspects of peer pressure. This research is a review of the existing literature on the positive and negative aspects of peer influence among adolescents in relation to academic performance and socialization.

Peer pressure has negative connotations that imply compulsion or persuasion, whereas socialization is a positive term that refers to the transmission of skills and competencies. ... A domain conceptualization of adolescent susceptibility to peer pressure. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 13, 57-80. 10.1111/1532-7795.1301002 [Google Scholar

Misbehaviour leaves parents and teachers frustrated, angry and anxious (Owens, 2002). The purpose of this study was to establish the influence of peer pressure on misbehaviour of adolescents at school in Namibia. Specifically, this study compared this relationship within advantaged and disadvantaged schools.

The Relationship Between Academic Pressure and Sense of Loneliness. Academic pressure is defined as stress related to academic performance. 15 Research has shown that the significant increase in loneliness during adolescence is often associated with poor academic performance. 16 One reason is that, in many countries, teachers, and parents place great emphasis on education, making educational ...

Gary E. Brown, Paul A. Dixon and J. Danny Hudson in their paper titled 'Effect of peer pressure on imitation of humour response in college students' in the year 1982, conducted research examining the effects of ... reinforcing the strength of peer pressure. A research was conducted by Dr. B. J, Casey in 2008, where teenagers volunteers ...

peer pressure through surveys that identify pressure as "when people your own age encourage ... Our paper is also related to a broader class of common agency models where some players can try to influence others' actions by offering them payments to take certain actions. This includes analyses by Prat and Rustichini (2004) who

1. Positive Pressure - "Peer pressure is positive when someone encourages or. supports you to do something good. e.g., partici pating in sports, joining clubs , trying n ew foods, doing ...

Relevant research shows that adolescents' problem behavior is persistent, which can significantly affect adult drinking, violence, and even committing crimes ... Teenagers with poor academic performance are vulnerable to peer pressure in the campus environment, and they are prone to feelings of inferiority, anxiety, and fear in their studies ...

Adolescent have higher tendency to experience peer pressure in school. Peer pressure is clustered in four categories such as social belongingness, curiosity, cultural-parenting orientation of parents and education, this research design used is descriptive correlation. The researchers conducted the survey among the students in the Senior High ...

The research followed good scientific practices as determined by the Finnish Advisory Board on Research Integrity 24 and it conforms with the Declaration of Helsinki. 25 Ethical approval (43/2015) was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the University of Turku. The participating organisations gave permission to conduct the study.

The suggested strategies to cope negative peer pressure will be help the vulnerable youth to cope peer pressure in effective manner. Discover the world's research 25+ million members

Peer pressure is an external factor that drives BIM learning and engineering practice, and a growing body of research highlights the value of peer pressure to the learning process and the benefits of its implementation as an important pedagogical approach to increasing student motivation.

This paper describes a new wave of research on the neurobehavioral substrates of adolescent decision making in peer contexts suggesting that the company of other teenagers ... without warning, at any point on the course. Peer context was manipulated by randomly assigning each group of three participants to play the game either individually ...