What is The Null Hypothesis & When Do You Reject The Null Hypothesis

Julia Simkus

Editor at Simply Psychology

BA (Hons) Psychology, Princeton University

Julia Simkus is a graduate of Princeton University with a Bachelor of Arts in Psychology. She is currently studying for a Master's Degree in Counseling for Mental Health and Wellness in September 2023. Julia's research has been published in peer reviewed journals.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

A null hypothesis is a statistical concept suggesting no significant difference or relationship between measured variables. It’s the default assumption unless empirical evidence proves otherwise.

The null hypothesis states no relationship exists between the two variables being studied (i.e., one variable does not affect the other).

The null hypothesis is the statement that a researcher or an investigator wants to disprove.

Testing the null hypothesis can tell you whether your results are due to the effects of manipulating the dependent variable or due to random chance.

How to Write a Null Hypothesis

Null hypotheses (H0) start as research questions that the investigator rephrases as statements indicating no effect or relationship between the independent and dependent variables.

It is a default position that your research aims to challenge or confirm.

For example, if studying the impact of exercise on weight loss, your null hypothesis might be:

There is no significant difference in weight loss between individuals who exercise daily and those who do not.

Examples of Null Hypotheses

| Research Question | Null Hypothesis |

|---|---|

| Do teenagers use cell phones more than adults? | Teenagers and adults use cell phones the same amount. |

| Do tomato plants exhibit a higher rate of growth when planted in compost rather than in soil? | Tomato plants show no difference in growth rates when planted in compost rather than soil. |

| Does daily meditation decrease the incidence of depression? | Daily meditation does not decrease the incidence of depression. |

| Does daily exercise increase test performance? | There is no relationship between daily exercise time and test performance. |

| Does the new vaccine prevent infections? | The vaccine does not affect the infection rate. |

| Does flossing your teeth affect the number of cavities? | Flossing your teeth has no effect on the number of cavities. |

When Do We Reject The Null Hypothesis?

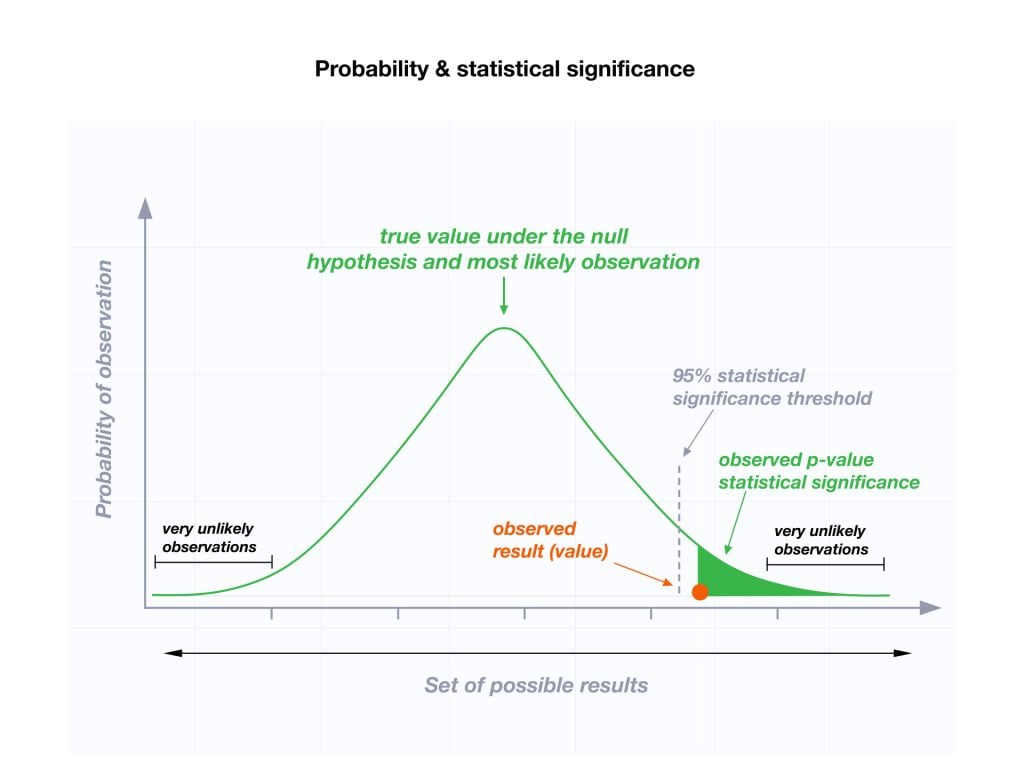

We reject the null hypothesis when the data provide strong enough evidence to conclude that it is likely incorrect. This often occurs when the p-value (probability of observing the data given the null hypothesis is true) is below a predetermined significance level.

If the collected data does not meet the expectation of the null hypothesis, a researcher can conclude that the data lacks sufficient evidence to back up the null hypothesis, and thus the null hypothesis is rejected.

Rejecting the null hypothesis means that a relationship does exist between a set of variables and the effect is statistically significant ( p > 0.05).

If the data collected from the random sample is not statistically significance , then the null hypothesis will be accepted, and the researchers can conclude that there is no relationship between the variables.

You need to perform a statistical test on your data in order to evaluate how consistent it is with the null hypothesis. A p-value is one statistical measurement used to validate a hypothesis against observed data.

Calculating the p-value is a critical part of null-hypothesis significance testing because it quantifies how strongly the sample data contradicts the null hypothesis.

The level of statistical significance is often expressed as a p -value between 0 and 1. The smaller the p-value, the stronger the evidence that you should reject the null hypothesis.

Usually, a researcher uses a confidence level of 95% or 99% (p-value of 0.05 or 0.01) as general guidelines to decide if you should reject or keep the null.

When your p-value is less than or equal to your significance level, you reject the null hypothesis.

In other words, smaller p-values are taken as stronger evidence against the null hypothesis. Conversely, when the p-value is greater than your significance level, you fail to reject the null hypothesis.

In this case, the sample data provides insufficient data to conclude that the effect exists in the population.

Because you can never know with complete certainty whether there is an effect in the population, your inferences about a population will sometimes be incorrect.

When you incorrectly reject the null hypothesis, it’s called a type I error. When you incorrectly fail to reject it, it’s called a type II error.

Why Do We Never Accept The Null Hypothesis?

The reason we do not say “accept the null” is because we are always assuming the null hypothesis is true and then conducting a study to see if there is evidence against it. And, even if we don’t find evidence against it, a null hypothesis is not accepted.

A lack of evidence only means that you haven’t proven that something exists. It does not prove that something doesn’t exist.

It is risky to conclude that the null hypothesis is true merely because we did not find evidence to reject it. It is always possible that researchers elsewhere have disproved the null hypothesis, so we cannot accept it as true, but instead, we state that we failed to reject the null.

One can either reject the null hypothesis, or fail to reject it, but can never accept it.

Why Do We Use The Null Hypothesis?

We can never prove with 100% certainty that a hypothesis is true; We can only collect evidence that supports a theory. However, testing a hypothesis can set the stage for rejecting or accepting this hypothesis within a certain confidence level.

The null hypothesis is useful because it can tell us whether the results of our study are due to random chance or the manipulation of a variable (with a certain level of confidence).

A null hypothesis is rejected if the measured data is significantly unlikely to have occurred and a null hypothesis is accepted if the observed outcome is consistent with the position held by the null hypothesis.

Rejecting the null hypothesis sets the stage for further experimentation to see if a relationship between two variables exists.

Hypothesis testing is a critical part of the scientific method as it helps decide whether the results of a research study support a particular theory about a given population. Hypothesis testing is a systematic way of backing up researchers’ predictions with statistical analysis.

It helps provide sufficient statistical evidence that either favors or rejects a certain hypothesis about the population parameter.

Purpose of a Null Hypothesis

- The primary purpose of the null hypothesis is to disprove an assumption.

- Whether rejected or accepted, the null hypothesis can help further progress a theory in many scientific cases.

- A null hypothesis can be used to ascertain how consistent the outcomes of multiple studies are.

Do you always need both a Null Hypothesis and an Alternative Hypothesis?

The null (H0) and alternative (Ha or H1) hypotheses are two competing claims that describe the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable. They are mutually exclusive, which means that only one of the two hypotheses can be true.

While the null hypothesis states that there is no effect in the population, an alternative hypothesis states that there is statistical significance between two variables.

The goal of hypothesis testing is to make inferences about a population based on a sample. In order to undertake hypothesis testing, you must express your research hypothesis as a null and alternative hypothesis. Both hypotheses are required to cover every possible outcome of the study.

What is the difference between a null hypothesis and an alternative hypothesis?

The alternative hypothesis is the complement to the null hypothesis. The null hypothesis states that there is no effect or no relationship between variables, while the alternative hypothesis claims that there is an effect or relationship in the population.

It is the claim that you expect or hope will be true. The null hypothesis and the alternative hypothesis are always mutually exclusive, meaning that only one can be true at a time.

What are some problems with the null hypothesis?

One major problem with the null hypothesis is that researchers typically will assume that accepting the null is a failure of the experiment. However, accepting or rejecting any hypothesis is a positive result. Even if the null is not refuted, the researchers will still learn something new.

Why can a null hypothesis not be accepted?

We can either reject or fail to reject a null hypothesis, but never accept it. If your test fails to detect an effect, this is not proof that the effect doesn’t exist. It just means that your sample did not have enough evidence to conclude that it exists.

We can’t accept a null hypothesis because a lack of evidence does not prove something that does not exist. Instead, we fail to reject it.

Failing to reject the null indicates that the sample did not provide sufficient enough evidence to conclude that an effect exists.

If the p-value is greater than the significance level, then you fail to reject the null hypothesis.

Is a null hypothesis directional or non-directional?

A hypothesis test can either contain an alternative directional hypothesis or a non-directional alternative hypothesis. A directional hypothesis is one that contains the less than (“<“) or greater than (“>”) sign.

A nondirectional hypothesis contains the not equal sign (“≠”). However, a null hypothesis is neither directional nor non-directional.

A null hypothesis is a prediction that there will be no change, relationship, or difference between two variables.

The directional hypothesis or nondirectional hypothesis would then be considered alternative hypotheses to the null hypothesis.

Gill, J. (1999). The insignificance of null hypothesis significance testing. Political research quarterly , 52 (3), 647-674.

Krueger, J. (2001). Null hypothesis significance testing: On the survival of a flawed method. American Psychologist , 56 (1), 16.

Masson, M. E. (2011). A tutorial on a practical Bayesian alternative to null-hypothesis significance testing. Behavior research methods , 43 , 679-690.

Nickerson, R. S. (2000). Null hypothesis significance testing: a review of an old and continuing controversy. Psychological methods , 5 (2), 241.

Rozeboom, W. W. (1960). The fallacy of the null-hypothesis significance test. Psychological bulletin , 57 (5), 416.

- Skip to secondary menu

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Statistics By Jim

Making statistics intuitive

Null Hypothesis: Definition, Rejecting & Examples

By Jim Frost 6 Comments

What is a Null Hypothesis?

The null hypothesis in statistics states that there is no difference between groups or no relationship between variables. It is one of two mutually exclusive hypotheses about a population in a hypothesis test.

- Null Hypothesis H 0 : No effect exists in the population.

- Alternative Hypothesis H A : The effect exists in the population.

In every study or experiment, researchers assess an effect or relationship. This effect can be the effectiveness of a new drug, building material, or other intervention that has benefits. There is a benefit or connection that the researchers hope to identify. Unfortunately, no effect may exist. In statistics, we call this lack of an effect the null hypothesis. Researchers assume that this notion of no effect is correct until they have enough evidence to suggest otherwise, similar to how a trial presumes innocence.

In this context, the analysts don’t necessarily believe the null hypothesis is correct. In fact, they typically want to reject it because that leads to more exciting finds about an effect or relationship. The new vaccine works!

You can think of it as the default theory that requires sufficiently strong evidence to reject. Like a prosecutor, researchers must collect sufficient evidence to overturn the presumption of no effect. Investigators must work hard to set up a study and a data collection system to obtain evidence that can reject the null hypothesis.

Related post : What is an Effect in Statistics?

Null Hypothesis Examples

Null hypotheses start as research questions that the investigator rephrases as a statement indicating there is no effect or relationship.

| Does the vaccine prevent infections? | The vaccine does not affect the infection rate. |

| Does the new additive increase product strength? | The additive does not affect mean product strength. |

| Does the exercise intervention increase bone mineral density? | The intervention does not affect bone mineral density. |

| As screen time increases, does test performance decrease? | There is no relationship between screen time and test performance. |

After reading these examples, you might think they’re a bit boring and pointless. However, the key is to remember that the null hypothesis defines the condition that the researchers need to discredit before suggesting an effect exists.

Let’s see how you reject the null hypothesis and get to those more exciting findings!

When to Reject the Null Hypothesis

So, you want to reject the null hypothesis, but how and when can you do that? To start, you’ll need to perform a statistical test on your data. The following is an overview of performing a study that uses a hypothesis test.

The first step is to devise a research question and the appropriate null hypothesis. After that, the investigators need to formulate an experimental design and data collection procedures that will allow them to gather data that can answer the research question. Then they collect the data. For more information about designing a scientific study that uses statistics, read my post 5 Steps for Conducting Studies with Statistics .

After data collection is complete, statistics and hypothesis testing enter the picture. Hypothesis testing takes your sample data and evaluates how consistent they are with the null hypothesis. The p-value is a crucial part of the statistical results because it quantifies how strongly the sample data contradict the null hypothesis.

When the sample data provide sufficient evidence, you can reject the null hypothesis. In a hypothesis test, this process involves comparing the p-value to your significance level .

Rejecting the Null Hypothesis

Reject the null hypothesis when the p-value is less than or equal to your significance level. Your sample data favor the alternative hypothesis, which suggests that the effect exists in the population. For a mnemonic device, remember—when the p-value is low, the null must go!

When you can reject the null hypothesis, your results are statistically significant. Learn more about Statistical Significance: Definition & Meaning .

Failing to Reject the Null Hypothesis

Conversely, when the p-value is greater than your significance level, you fail to reject the null hypothesis. The sample data provides insufficient data to conclude that the effect exists in the population. When the p-value is high, the null must fly!

Note that failing to reject the null is not the same as proving it. For more information about the difference, read my post about Failing to Reject the Null .

That’s a very general look at the process. But I hope you can see how the path to more exciting findings depends on being able to rule out the less exciting null hypothesis that states there’s nothing to see here!

Let’s move on to learning how to write the null hypothesis for different types of effects, relationships, and tests.

Related posts : How Hypothesis Tests Work and Interpreting P-values

How to Write a Null Hypothesis

The null hypothesis varies by the type of statistic and hypothesis test. Remember that inferential statistics use samples to draw conclusions about populations. Consequently, when you write a null hypothesis, it must make a claim about the relevant population parameter . Further, that claim usually indicates that the effect does not exist in the population. Below are typical examples of writing a null hypothesis for various parameters and hypothesis tests.

Related posts : Descriptive vs. Inferential Statistics and Populations, Parameters, and Samples in Inferential Statistics

Group Means

T-tests and ANOVA assess the differences between group means. For these tests, the null hypothesis states that there is no difference between group means in the population. In other words, the experimental conditions that define the groups do not affect the mean outcome. Mu (µ) is the population parameter for the mean, and you’ll need to include it in the statement for this type of study.

For example, an experiment compares the mean bone density changes for a new osteoporosis medication. The control group does not receive the medicine, while the treatment group does. The null states that the mean bone density changes for the control and treatment groups are equal.

- Null Hypothesis H 0 : Group means are equal in the population: µ 1 = µ 2 , or µ 1 – µ 2 = 0

- Alternative Hypothesis H A : Group means are not equal in the population: µ 1 ≠ µ 2 , or µ 1 – µ 2 ≠ 0.

Group Proportions

Proportions tests assess the differences between group proportions. For these tests, the null hypothesis states that there is no difference between group proportions. Again, the experimental conditions did not affect the proportion of events in the groups. P is the population proportion parameter that you’ll need to include.

For example, a vaccine experiment compares the infection rate in the treatment group to the control group. The treatment group receives the vaccine, while the control group does not. The null states that the infection rates for the control and treatment groups are equal.

- Null Hypothesis H 0 : Group proportions are equal in the population: p 1 = p 2 .

- Alternative Hypothesis H A : Group proportions are not equal in the population: p 1 ≠ p 2 .

Correlation and Regression Coefficients

Some studies assess the relationship between two continuous variables rather than differences between groups.

In these studies, analysts often use either correlation or regression analysis . For these tests, the null states that there is no relationship between the variables. Specifically, it says that the correlation or regression coefficient is zero. As one variable increases, there is no tendency for the other variable to increase or decrease. Rho (ρ) is the population correlation parameter and beta (β) is the regression coefficient parameter.

For example, a study assesses the relationship between screen time and test performance. The null states that there is no correlation between this pair of variables. As screen time increases, test performance does not tend to increase or decrease.

- Null Hypothesis H 0 : The correlation in the population is zero: ρ = 0.

- Alternative Hypothesis H A : The correlation in the population is not zero: ρ ≠ 0.

For all these cases, the analysts define the hypotheses before the study. After collecting the data, they perform a hypothesis test to determine whether they can reject the null hypothesis.

The preceding examples are all for two-tailed hypothesis tests. To learn about one-tailed tests and how to write a null hypothesis for them, read my post One-Tailed vs. Two-Tailed Tests .

Related post : Understanding Correlation

Neyman, J; Pearson, E. S. (January 1, 1933). On the Problem of the most Efficient Tests of Statistical Hypotheses . Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A . 231 (694–706): 289–337.

Share this:

Reader Interactions

January 11, 2024 at 2:57 pm

Thanks for the reply.

January 10, 2024 at 1:23 pm

Hi Jim, In your comment you state that equivalence test null and alternate hypotheses are reversed. For hypothesis tests of data fits to a probability distribution, the null hypothesis is that the probability distribution fits the data. Is this correct?

January 10, 2024 at 2:15 pm

Those two separate things, equivalence testing and normality tests. But, yes, you’re correct for both.

Hypotheses are switched for equivalence testing. You need to “work” (i.e., collect a large sample of good quality data) to be able to reject the null that the groups are different to be able to conclude they’re the same.

With typical hypothesis tests, if you have low quality data and a low sample size, you’ll fail to reject the null that they’re the same, concluding they’re equivalent. But that’s more a statement about the low quality and small sample size than anything to do with the groups being equal.

So, equivalence testing make you work to obtain a finding that the groups are the same (at least within some amount you define as a trivial difference).

For normality testing, and other distribution tests, the null states that the data follow the distribution (normal or whatever). If you reject the null, you have sufficient evidence to conclude that your sample data don’t follow the probability distribution. That’s a rare case where you hope to fail to reject the null. And it suffers from the problem I describe above where you might fail to reject the null simply because you have a small sample size. In that case, you’d conclude the data follow the probability distribution but it’s more that you don’t have enough data for the test to register the deviation. In this scenario, if you had a larger sample size, you’d reject the null and conclude it doesn’t follow that distribution.

I don’t know of any equivalence testing type approach for distribution fit tests where you’d need to work to show the data follow a distribution, although I haven’t looked for one either!

February 20, 2022 at 9:26 pm

Is a null hypothesis regularly (always) stated in the negative? “there is no” or “does not”

February 23, 2022 at 9:21 pm

Typically, the null hypothesis includes an equal sign. The null hypothesis states that the population parameter equals a particular value. That value is usually one that represents no effect. In the case of a one-sided hypothesis test, the null still contains an equal sign but it’s “greater than or equal to” or “less than or equal to.” If you wanted to translate the null hypothesis from its native mathematical expression, you could use the expression “there is no effect.” But the mathematical form more specifically states what it’s testing.

It’s the alternative hypothesis that typically contains does not equal.

There are some exceptions. For example, in an equivalence test where the researchers want to show that two things are equal, the null hypothesis states that they’re not equal.

In short, the null hypothesis states the condition that the researchers hope to reject. They need to work hard to set up an experiment and data collection that’ll gather enough evidence to be able to reject the null condition.

February 15, 2022 at 9:32 am

Dear sir I always read your notes on Research methods.. Kindly tell is there any available Book on all these..wonderfull Urgent

Comments and Questions Cancel reply

Null Hypothesis Definition and Examples, How to State

What is the null hypothesis, how to state the null hypothesis, null hypothesis overview.

Why is it Called the “Null”?

The word “null” in this context means that it’s a commonly accepted fact that researchers work to nullify . It doesn’t mean that the statement is null (i.e. amounts to nothing) itself! (Perhaps the term should be called the “nullifiable hypothesis” as that might cause less confusion).

Why Do I need to Test it? Why not just prove an alternate one?

The short answer is, as a scientist, you are required to ; It’s part of the scientific process. Science uses a battery of processes to prove or disprove theories, making sure than any new hypothesis has no flaws. Including both a null and an alternate hypothesis is one safeguard to ensure your research isn’t flawed. Not including the null hypothesis in your research is considered very bad practice by the scientific community. If you set out to prove an alternate hypothesis without considering it, you are likely setting yourself up for failure. At a minimum, your experiment will likely not be taken seriously.

- Null hypothesis : H 0 : The world is flat.

- Alternate hypothesis: The world is round.

Several scientists, including Copernicus , set out to disprove the null hypothesis. This eventually led to the rejection of the null and the acceptance of the alternate. Most people accepted it — the ones that didn’t created the Flat Earth Society !. What would have happened if Copernicus had not disproved the it and merely proved the alternate? No one would have listened to him. In order to change people’s thinking, he first had to prove that their thinking was wrong .

How to State the Null Hypothesis from a Word Problem

You’ll be asked to convert a word problem into a hypothesis statement in statistics that will include a null hypothesis and an alternate hypothesis . Breaking your problem into a few small steps makes these problems much easier to handle.

Step 2: Convert the hypothesis to math . Remember that the average is sometimes written as μ.

H 1 : μ > 8.2

Broken down into (somewhat) English, that’s H 1 (The hypothesis): μ (the average) > (is greater than) 8.2

Step 3: State what will happen if the hypothesis doesn’t come true. If the recovery time isn’t greater than 8.2 weeks, there are only two possibilities, that the recovery time is equal to 8.2 weeks or less than 8.2 weeks.

H 0 : μ ≤ 8.2

Broken down again into English, that’s H 0 (The null hypothesis): μ (the average) ≤ (is less than or equal to) 8.2

How to State the Null Hypothesis: Part Two

But what if the researcher doesn’t have any idea what will happen.

Example Problem: A researcher is studying the effects of radical exercise program on knee surgery patients. There is a good chance the therapy will improve recovery time, but there’s also the possibility it will make it worse. Average recovery times for knee surgery patients is 8.2 weeks.

Step 1: State what will happen if the experiment doesn’t make any difference. That’s the null hypothesis–that nothing will happen. In this experiment, if nothing happens, then the recovery time will stay at 8.2 weeks.

H 0 : μ = 8.2

Broken down into English, that’s H 0 (The null hypothesis): μ (the average) = (is equal to) 8.2

Step 2: Figure out the alternate hypothesis . The alternate hypothesis is the opposite of the null hypothesis. In other words, what happens if our experiment makes a difference?

H 1 : μ ≠ 8.2

In English again, that’s H 1 (The alternate hypothesis): μ (the average) ≠ (is not equal to) 8.2

That’s How to State the Null Hypothesis!

Check out our Youtube channel for more stats tips!

Gonick, L. (1993). The Cartoon Guide to Statistics . HarperPerennial. Kotz, S.; et al., eds. (2006), Encyclopedia of Statistical Sciences , Wiley.

Stack Exchange Network

Stack Exchange network consists of 183 Q&A communities including Stack Overflow , the largest, most trusted online community for developers to learn, share their knowledge, and build their careers.

Q&A for work

Connect and share knowledge within a single location that is structured and easy to search.

Why can't we accept the null hypothesis, but we can accept the alternative hypothesis?

I understand it's reasonable only to not reject the null hypothesis. But why can we accept the alternative hypothesis?

What's the difference?

- hypothesis-testing

- 5 $\begingroup$ Rejecting the null hypothesis could be written up as accepting the alternative. Many people would rather not say that. Many people would rather focus on confidence intervals! Or something Bayesian. $\endgroup$ – Nick Cox Commented Aug 31, 2022 at 18:39

- 6 $\begingroup$ Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence! $\endgroup$ – Ben Commented Aug 31, 2022 at 18:39

- 4 $\begingroup$ @Ben many people would disagree philosophy.stackexchange.com/questions/92546/… $\endgroup$ – fblundun Commented Aug 31, 2022 at 21:57

- 3 $\begingroup$ I am sorry I don't know which answer to accept because I can't understand any of them. $\endgroup$ – user900476 Commented Sep 1, 2022 at 13:31

- 3 $\begingroup$ @user900476 You are in no way obliged to accept any answer as long as none is satisfactory. stackoverflow.com/help/someone-answers You may, however, consider clarifying what would define a better answer. $\endgroup$ – Bernhard Commented Sep 2, 2022 at 9:25

7 Answers 7

I'll start with a quote for context and to point to a helpful resource that might have an answer for the OP. It's from V. Amrhein, S. Greenland, and B. McShane. Scientists rise up against statistical significance. Nature , 567:305–307, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-019-00857-9

We must learn to embrace uncertainty.

I understand it to mean that there is no need to state that we reject a hypothesis , accept a hypothesis , or don't reject a hypothesis to explain what we've learned from a statistical analysis. The accept/reject language implies certainty; statistics is better at quantifying uncertainty.

Note : I assume the question refers to making a binary reject/accept choice dictated by the significance (P ≤ 0.05) or non-significance (P > 0.05) of a p-value P.

The simplest way to understand hypothesis testing (NHST) — at least for me — is to keep in mind that p-values are probabilities about the data (not about the null and alternative hypotheses): Large p-value means that the data is consistent with the null hypothesis, small p-value means that the data is inconsistent with the null hypothesis. NHST doesn't tell us what hypothesis to reject and/or accept so that we have 100% certainty in our decision: hypothesis testing doesn't prove anything ٭ . The reason is that a p-value is computed by assuming the null hypothesis is true [3].

So rather than wondering if, on calculating P ≤ 0.05, it's correct to declare that you "reject the null hypothesis" (technically correct) or "accept the alternative hypothesis" (technically incorrect), don't make a reject/don't reject determination but report what you've learned from the data: report the p-value or, better yet, your estimate of the quantity of interest and its standard error or confidence interval.

٭ Probability ≠ proof. For illustration, see this story about a small p-value at CERN leading scientists to announce they might have discovered a brand new force of nature: New physics at the Large Hadron Collider? Scientists are excited, but it’s too soon to be sure . Includes a bonus explanation of p-values.

[1] S. Goodman. A dirty dozen: Twelve p-value misconceptions. Seminars in Hematology , 45(3):135–140, 2008. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.seminhematol.2008.04.003

All twelve misconceptions are important to study, understand and avoid. But Misconception #12 is particularly relevant to this question: It's not the case that A scientific conclusion or treatment policy should be based on whether or not the P value is significant.

Steven Goodman explains: "This misconception (...) is equivalent to saying that the magnitude of effect is not relevant, that only evidence relevant to a scientific conclusion is in the experiment at hand, and that both beliefs and actions flow directly from the statistical results."

[2] Using p-values to test a hypothesis in Improving Your Statistical Inferences by Daniël Lakens.

This is my favorite explanation of p-values, their history, theory and misapplications. Has lots of examples from the social sciences.

[3] What is the meaning of p values and t values in statistical tests?

- 1 $\begingroup$ @whuber When did p-values and frequentist statistics started conditioning on the data? If we want to condition on the data, then we goes Bayesian. But I'll edit with my answer with some pointers to papers. $\endgroup$ – dipetkov Commented Aug 31, 2022 at 19:41

- 2 $\begingroup$ I did not mean "condition" in the sense of assuming a probability distribution for the parameters; only that we are, of course, not making decisions about the hypotheses in vacuo but are basing them on the data. What you write here appears to fly in the face of all the literature on hypothesis testing. Why, after all, would anyone even bother if it weren't for the prospect that the test could tell us something about the state of nature? $\endgroup$ – whuber ♦ Commented Aug 31, 2022 at 19:45

- 3 $\begingroup$ I haven't complained about any imprecision. As you are gently hinting, I have been imprecise in these comments myself. My original concern what that your statements about interpreting NHSTs looked wrong. $\endgroup$ – whuber ♦ Commented Aug 31, 2022 at 21:23

- 3 $\begingroup$ For continuous data the probability of observed what we observed is zero, so the P-value is the probability of observing something more extreme than our observed data. So the above answer needs to be more nuanced. $\endgroup$ – Frank Harrell Commented Sep 1, 2022 at 15:42

- 2 $\begingroup$ What does 'et al.' mean? Could you change that into simple English to make your answer less intimidating. $\endgroup$ – Sextus Empiricus Commented Sep 1, 2022 at 20:13

Say you have the hypothesis

"on stackexchange there is not yet an answer to my question"

When you randomly sample 1000 questions then you might find zero answers. Based on this, can you 'accept' the null hypothesis?

You can read about this among many older questions and answers, for instance:

- Why do statisticians say a non-significant result means "you can't reject the null" as opposed to accepting the null hypothesis?

- Why do we need alternative hypothesis?

- Is it possible to accept the alternative hypothesis?

Also check out the questions about two one-sided tests (TOST) which is about formulating the statement behind a null hypothesis in a way such that it can be a statement that you can potentially 'accept'.

More seriously, a problem with the question is that it is unclear. What does 'accept' actually mean?

And also, it is a loaded question . It asks for something that is not true. Like 'why is it that the earth is flat, but the moon is round?' .

There is no 'acceptance' of an alternative theory. Or at least, when we 'accept' some alternative hypothesis then either:

- Hypothesis testing: the alternative theory is extremely broad and reads as 'something else than the null hypothesis is true'. Whatever this 'something else' means, that is left open. There is no 'acceptance' of a particular theory. See also: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Falsifiability

- Expression of significance: or 'acceptance' means that we observed an effect, and consider it as a 'significant' effect. There is no literal 'acceptance' of some theory/hypothesis here. There is just the consideration that we found that the data shows there is some effect and it is significantly different from a case when to there would be zero effect. Whether this means that the alternative theory should be accepted, that is not explicitly stated and should also not be assumed implicitly. The alternative hypothesis (related to the effect) works for the present data, but that is different from being accepted, (it just has not been rejected yet).

In addition to the answers given by highly experienced users here, I'd like to offer a less formal and hopefully more intuitive view.

Briefly, the " null hypothesis " is considered accepted, unless there is some compelling evidence to reject it in favour of an alternative.

It helps to look at it from the decision-making perspective. Tests---not only statistical---help us make decisions. Before performing the test, we have one course of action. After performing the test, we may either keep the course or change it, depending on the test result. The null hypothesis is the default course of action, given no or not enough information.

For example, imagine you are a flying an aeroplane. Without a reason to do otherwise, you'll probably fly it straight towards your destination. But, the whole time you'd be performing "tests", like checking your radar whether there is some unexpected obstacle on your path. If the radar shows no obstacle, you'll keep your course. This is the default decision, which you'd most likely make even if you had to fly without a radar. I mean, what else could you do? Wildly zigzag through the sky?

In this analogy, the null hypothesis is that there is no reason to change the course. You don't "accept" it as a result of the test, because it has already been accepted before you took a look at the radar. Only if you discover an obstacle, you'd reject it in favour of changing the course.

Or, as a more real-world example, imagine developing a new drug for a disease. The default status, before you perform any trials at all, is that the drug is not approved . You may run in vitro , in vivo , and clinical trials to prove that your drug is safe and helpful. If that fails, the drug remains "not approved". Again, there is nothing to " accept ", or at least nothing with practical consequences. Only with compelling evidence of the drug's usefulness its status can change to "approved".

As you can see from the examples, which hypothesis is treated as " null " is somewhat subjective. For example, is "homeopathy works" null , or does it need evidence to be accepted? That depends on your prior beliefs and experience. If you grew up in a homeopathic home, you are likely to consider it to work by default and would't change your mind unless you see strong evidence against it (or maybe ever). But, this can get arbitrarily philosophical / psychological.

- 1 $\begingroup$ (+1: " answers given by highly experienced users " you aren't exacllty a spring chicken on this website yourself...) $\endgroup$ – usεr11852 Commented Sep 2, 2022 at 14:52

- $\begingroup$ Your plane example seems to have little to do with hypothesis testing and much to do with estimation and optimization. Can you explain how rejecting the null hypothesis of "flying straight" points out the direction in which to fly instead? $\endgroup$ – dipetkov Commented Sep 2, 2022 at 20:09

- $\begingroup$ @dipetkov It doesn't, much like many statistical tests - think of a two-sided t-test. The direction then needs to be decided based on further information. But, if we failed to reject the null hypothesis, we wouldn't bother collecting further information. $\endgroup$ – Igor F. Commented Sep 8, 2022 at 7:55

- $\begingroup$ Hm. While in a plane in the middle of the sky? I'll probably bother collecting further information. By the way, I like your example because it illustrates (it seems to me) that usually we'd like to learn more than what NHST can give us. $\endgroup$ – dipetkov Commented Sep 8, 2022 at 8:29

- $\begingroup$ Furthermore, "wouldn't bother collecting further information" means that you've accepted the null hypothesis. Not rejecting the null hypothesis means that you acknowledge other hypotheses are still in play. That would correspond to "keep going straight for now while collecting further information". In practice the more natural formulation is to ask: "What's the optimal direction to be flying in right now?" $\endgroup$ – dipetkov Commented Sep 8, 2022 at 9:54

We should not accept the research/alternative hypothesis.

The main value of a null hypothesis statistical test is to help the researcher adopt a degree of self-skepticism about their research hypothesis. The null hypothesis is the hypothesis we need to nullify in order to proceed with promulgation of our research hypothesis. It doesn't mean the alternative hypothesis is right, just that it hasn't failed a test - we have managed to get over a (usually fairly low) hurdle, nothing more. I view this a little like naive falsificationism - we can't prove a theory, only disprove it†, so all we can say is that a theory has survived an attempt to refute it. IIRC Popper says that the test "corroborates" a theory, but this is a long way short of showing it is true (or accepting it).

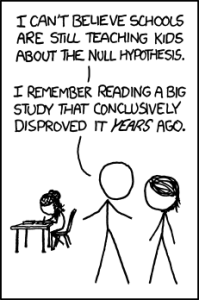

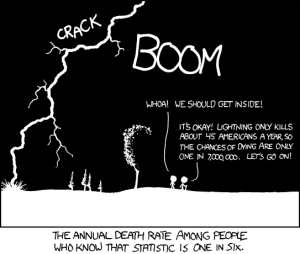

A good example of this is the classic XKCD cartoon (see this question ):

Is it reasonable for the frequentist to "accept" the alternative hypothesis that the sun has gone nova? No!!! In this case, the most obvious reason is that the analysis doesn't consider the prior probabilities of the two hypotheses, which a frequentist would do by setting a much more stringent significance level. But also there may be explanations for the neutrinos that have nothing to do with the sun going nova (perhaps I have just come back from a visit to the Cretaceous to see the dinosaurs, and you've detected my return to this timeline). So rejecting the null hypothesis doesn't mean the alternative hypothesis is true.

A frequentist analysis fundamentally cannot assign a probability to the truth of a hypothesis, so it doesn't give much of a basis for accepting it. The "we reject the null hypothesis" is basically a an incantation in a ritual. It doesn't literally mean that we are discarding the null hypothesis as we are confident that it is false. It is just a convention that we proceed with the alternative hypothesis if we can "reject" the null hypothesis. There is no mathematical requirement that the null hypothesis is wrong. This isn't necessarily a bad thing, it is just best to take it as technical jargon and not read too much into the actual words.

Unfortunately the semantics of Null Hypothesis Statistical Tests are rather subtle, and often not a direct answer to the question we actually want to pose, so I would recommend just saying "we reject the null hypothesis" or "we fail to reject the null hypothesis" and leave it at that. Those that understand the semantics will draw the appropriate conclusion. Those who don't understand the semantics won't be mislead into thinking that the alternative hypothesis has been shown to be true (by accepting it).

† Sadly, we can't really disprove them either .

- 1 $\begingroup$ +1 I think this is the best answer. Hopefully the OP will revisit the question and let us know whether he/she/they understood it. $\endgroup$ – dipetkov Commented Sep 7, 2022 at 7:22

The answer depends on whether you are using a pre-defined critical value (or p-value threshold like p<0.05) in a hypothesis test that yields a decision (a Neyman–Pearsonian hypothesis test), or whether you are using the magnitude of the actual p-value as an index of the evidence in the data (a [neo-]Fisherian significance test).

If you are doing a hypothesis test then you are working with a set of rules that grant you a pre-set confidence of long-run performance of the test procedure. The way that the rules can give confidence about long-run test performance is by specifying what decision applies depending on the data, and the decision relates to the acceptance or non-acceptance (yes, that is rejection as far as I am concerned) of the null hypothesis. Rejection of the statistical null hypothesis can be thought of as acceptance of another hypothesis, but that other hypothesis can be nothing more than a set of all not-the-null hypotheses that exist within the statistical model. Accepting that not-the-null hypothesis is not very informative and so it is not unreasonable to simply say that the test rejects the null but does not accept anything else.

There is (sometimes) a specific 'alternative' hypothesis specified for a hypothesis test: the hypothetical effect size plugged into the pre-experiment power analysis used to set the sample size. That 'alternative' hypothesis IS NOT tested by the hypothesis test and has very little meaning once the data are available.

If you are doing a significance test then a small p-value implies that the data are inconsistent with the statistical model's expectations regarding probable observations where the null hypothesis is true. The analyst can then use that evidence to make a scientific inference. The scientific inference might well include an interim rejection of the statistical null hypothesis and acceptance of a specific 'alternative' hypothesis of scientific interest. It depends on the information available and the scientific objectives, and it is a process that is very rarely considered in statistical instruction.

See this open access chapter for much more detail: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/164_2019_286

- $\begingroup$ Thank you for the reference! Could you please clarify this: The "pre-set confidence of long-run performance" is assuming the null hypothesis is true, right? But if there is a possibility the null hypothesis is false, can we really say anything? $\endgroup$ – Mankka Commented Sep 1, 2022 at 8:27

- $\begingroup$ @Mankka The pre-set confidence is regarding the long run false positive error rate. Can we say anything? Well, within the Neyman–Pearsonian framework you cannot say anything about the particular hypothesis of concern because that framework deals with only the global error rates. The Fisherian significance test does say things about the particular experiment. That's the difference. $\endgroup$ – Michael Lew Commented Sep 1, 2022 at 20:04

Within the Bayesian framework you can "accept the null hypothesis" in the sense that the posterior probability of a point null hypothesis can tend to one with increasing sample size. This requires that the null hypothesis is exactly true and that you're willing to represent this in your prior by a point mass. Lindley (1957, p. 188) gives two examples where this is arguably reasonable: testing for linkage in genetics, and testing someone for telepathic powers. In addition, your prior on the parameter of interest must be proper under the alternative hypothesis. See for example this answer .

"Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence." Carl Sagan.

The null hypothesis specifies no effect, that is absence of effect. You reject the null if the results are statistically significant, that is, when you have evidence for rejecting the null. If the results are not statistically significant, what you have is absence of evidence.

Your Answer

Sign up or log in, post as a guest.

Required, but never shown

By clicking “Post Your Answer”, you agree to our terms of service and acknowledge you have read our privacy policy .

Not the answer you're looking for? Browse other questions tagged hypothesis-testing or ask your own question .

- Featured on Meta

- We've made changes to our Terms of Service & Privacy Policy - July 2024

- Bringing clarity to status tag usage on meta sites

Hot Network Questions

- grep command fails with out-of-memeory error

- What might cause these striations in this solder joint?

- What is the difference between an `.iso` OS for a network and an `.iso` OS for CD?

- Can I use rear (thru) axle with crack for a few rides, before getting a new one?

- Is it OK to use the same field in the database to store both a percentage rate and a fixed money fee?

- Can you successfully substitute pickled onions for baby onions in Coq Au Vin?

- Fast circular buffer

- Can objective morality be derived as a corollary from the assumption of God's existence?

- "Knocking it out of the park" sports metaphor American English vs British English?

- Why don't we observe protons deflecting in J.J. Thomson's experiment?

- Version of Dracula (Bram Stoker)

- Looking for source of story about returning a lost object

- bash script quoting frustration

- How do we know for sure that the dedekind axiom is logically independent of the other axioms?

- Can a "sharp turn" on a trace with an SMD resistor also present a risk of reflection?

- Home water pressure higher than city water pressure?

- How soon to fire rude and chaotic PhD student?

- Does the overall mAh of the battery add up when batteries are parallel?

- I am a fifteen-year-old from India planning to fly to Germany alone (without my parents accompanying me) to see my relatives.What documents do I need?

- A binary sequence such that sum of every 10 consecutive terms is divisible by 3 is necessarily periodic?

- Are there any virtues in virtue ethics that cannot be plausibly grounded in more fundamental utilitarian principles?

- How to \AddToHook{begindocument}{<code>}, but avoid the log of font initialisation in l3build testing?

- Would it take less thrust overall to put an object into higher orbit?

- What Christian ideas are found in the New Testament that are not found in the Old Testament?

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Inferential Statistics

Learning Objectives

- Explain the purpose of null hypothesis testing, including the role of sampling error.

- Describe the basic logic of null hypothesis testing.

- Describe the role of relationship strength and sample size in determining statistical significance and make reasonable judgments about statistical significance based on these two factors.

The Purpose of Null Hypothesis Testing

As we have seen, psychological research typically involves measuring one or more variables in a sample and computing descriptive summary data (e.g., means, correlation coefficients) for those variables. These descriptive data for the sample are called statistics . In general, however, the researcher’s goal is not to draw conclusions about that sample but to draw conclusions about the population that the sample was selected from. Thus researchers must use sample statistics to draw conclusions about the corresponding values in the population. These corresponding values in the population are called parameters . Imagine, for example, that a researcher measures the number of depressive symptoms exhibited by each of 50 adults with clinical depression and computes the mean number of symptoms. The researcher probably wants to use this sample statistic (the mean number of symptoms for the sample) to draw conclusions about the corresponding population parameter (the mean number of symptoms for adults with clinical depression).

Unfortunately, sample statistics are not perfect estimates of their corresponding population parameters. This is because there is a certain amount of random variability in any statistic from sample to sample. The mean number of depressive symptoms might be 8.73 in one sample of adults with clinical depression, 6.45 in a second sample, and 9.44 in a third—even though these samples are selected randomly from the same population. Similarly, the correlation (Pearson’s r ) between two variables might be +.24 in one sample, −.04 in a second sample, and +.15 in a third—again, even though these samples are selected randomly from the same population. This random variability in a statistic from sample to sample is called sampling error . (Note that the term error here refers to random variability and does not imply that anyone has made a mistake. No one “commits a sampling error.”)

One implication of this is that when there is a statistical relationship in a sample, it is not always clear that there is a statistical relationship in the population. A small difference between two group means in a sample might indicate that there is a small difference between the two group means in the population. But it could also be that there is no difference between the means in the population and that the difference in the sample is just a matter of sampling error. Similarly, a Pearson’s r value of −.29 in a sample might mean that there is a negative relationship in the population. But it could also be that there is no relationship in the population and that the relationship in the sample is just a matter of sampling error.

In fact, any statistical relationship in a sample can be interpreted in two ways:

- There is a relationship in the population, and the relationship in the sample reflects this.

- There is no relationship in the population, and the relationship in the sample reflects only sampling error.

The purpose of null hypothesis testing is simply to help researchers decide between these two interpretations.

The Logic of Null Hypothesis Testing

Null hypothesis testing (often called null hypothesis significance testing or NHST) is a formal approach to deciding between two interpretations of a statistical relationship in a sample. One interpretation is called the null hypothesis (often symbolized H 0 and read as “H-zero”). This is the idea that there is no relationship in the population and that the relationship in the sample reflects only sampling error. Informally, the null hypothesis is that the sample relationship “occurred by chance.” The other interpretation is called the alternative hypothesis (often symbolized as H 1 ). This is the idea that there is a relationship in the population and that the relationship in the sample reflects this relationship in the population.

Again, every statistical relationship in a sample can be interpreted in either of these two ways: It might have occurred by chance, or it might reflect a relationship in the population. So researchers need a way to decide between them. Although there are many specific null hypothesis testing techniques, they are all based on the same general logic. The steps are as follows:

- Assume for the moment that the null hypothesis is true. There is no relationship between the variables in the population.

- Determine how likely the sample relationship would be if the null hypothesis were true.

- If the sample relationship would be extremely unlikely, then reject the null hypothesis in favor of the alternative hypothesis. If it would not be extremely unlikely, then retain the null hypothesis .

Following this logic, we can begin to understand why Mehl and his colleagues concluded that there is no difference in talkativeness between women and men in the population. In essence, they asked the following question: “If there were no difference in the population, how likely is it that we would find a small difference of d = 0.06 in our sample?” Their answer to this question was that this sample relationship would be fairly likely if the null hypothesis were true. Therefore, they retained the null hypothesis—concluding that there is no evidence of a sex difference in the population. We can also see why Kanner and his colleagues concluded that there is a correlation between hassles and symptoms in the population. They asked, “If the null hypothesis were true, how likely is it that we would find a strong correlation of +.60 in our sample?” Their answer to this question was that this sample relationship would be fairly unlikely if the null hypothesis were true. Therefore, they rejected the null hypothesis in favor of the alternative hypothesis—concluding that there is a positive correlation between these variables in the population.

A crucial step in null hypothesis testing is finding the probability of the sample result or a more extreme result if the null hypothesis were true (Lakens, 2017). [1] This probability is called the p value . A low p value means that the sample or more extreme result would be unlikely if the null hypothesis were true and leads to the rejection of the null hypothesis. A p value that is not low means that the sample or more extreme result would be likely if the null hypothesis were true and leads to the retention of the null hypothesis. But how low must the p value criterion be before the sample result is considered unlikely enough to reject the null hypothesis? In null hypothesis testing, this criterion is called α (alpha) and is almost always set to .05. If there is a 5% chance or less of a result at least as extreme as the sample result if the null hypothesis were true, then the null hypothesis is rejected. When this happens, the result is said to be statistically significant . If there is greater than a 5% chance of a result as extreme as the sample result when the null hypothesis is true, then the null hypothesis is retained. This does not necessarily mean that the researcher accepts the null hypothesis as true—only that there is not currently enough evidence to reject it. Researchers often use the expression “fail to reject the null hypothesis” rather than “retain the null hypothesis,” but they never use the expression “accept the null hypothesis.”

The Misunderstood p Value

The p value is one of the most misunderstood quantities in psychological research (Cohen, 1994) [2] . Even professional researchers misinterpret it, and it is not unusual for such misinterpretations to appear in statistics textbooks!

The most common misinterpretation is that the p value is the probability that the null hypothesis is true—that the sample result occurred by chance. For example, a misguided researcher might say that because the p value is .02, there is only a 2% chance that the result is due to chance and a 98% chance that it reflects a real relationship in the population. But this is incorrect . The p value is really the probability of a result at least as extreme as the sample result if the null hypothesis were true. So a p value of .02 means that if the null hypothesis were true, a sample result this extreme would occur only 2% of the time.

You can avoid this misunderstanding by remembering that the p value is not the probability that any particular hypothesis is true or false. Instead, it is the probability of obtaining the sample result if the null hypothesis were true.

Role of Sample Size and Relationship Strength

Recall that null hypothesis testing involves answering the question, “If the null hypothesis were true, what is the probability of a sample result as extreme as this one?” In other words, “What is the p value?” It can be helpful to see that the answer to this question depends on just two considerations: the strength of the relationship and the size of the sample. Specifically, the stronger the sample relationship and the larger the sample, the less likely the result would be if the null hypothesis were true. That is, the lower the p value. This should make sense. Imagine a study in which a sample of 500 women is compared with a sample of 500 men in terms of some psychological characteristic, and Cohen’s d is a strong 0.50. If there were really no sex difference in the population, then a result this strong based on such a large sample should seem highly unlikely. Now imagine a similar study in which a sample of three women is compared with a sample of three men, and Cohen’s d is a weak 0.10. If there were no sex difference in the population, then a relationship this weak based on such a small sample should seem likely. And this is precisely why the null hypothesis would be rejected in the first example and retained in the second.

Of course, sometimes the result can be weak and the sample large, or the result can be strong and the sample small. In these cases, the two considerations trade off against each other so that a weak result can be statistically significant if the sample is large enough and a strong relationship can be statistically significant even if the sample is small. Table 13.1 shows roughly how relationship strength and sample size combine to determine whether a sample result is statistically significant. The columns of the table represent the three levels of relationship strength: weak, medium, and strong. The rows represent four sample sizes that can be considered small, medium, large, and extra large in the context of psychological research. Thus each cell in the table represents a combination of relationship strength and sample size. If a cell contains the word Yes , then this combination would be statistically significant for both Cohen’s d and Pearson’s r . If it contains the word No , then it would not be statistically significant for either. There is one cell where the decision for d and r would be different and another where it might be different depending on some additional considerations, which are discussed in Section 13.2 “Some Basic Null Hypothesis Tests”

| Sample Size | Weak | Medium | Strong |

| Small ( = 20) | No | No | = Maybe = Yes |

| Medium ( = 50) | No | Yes | Yes |

| Large ( = 100) | = Yes = No | Yes | Yes |

| Extra large ( = 500) | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Although Table 13.1 provides only a rough guideline, it shows very clearly that weak relationships based on medium or small samples are never statistically significant and that strong relationships based on medium or larger samples are always statistically significant. If you keep this lesson in mind, you will often know whether a result is statistically significant based on the descriptive statistics alone. It is extremely useful to be able to develop this kind of intuitive judgment. One reason is that it allows you to develop expectations about how your formal null hypothesis tests are going to come out, which in turn allows you to detect problems in your analyses. For example, if your sample relationship is strong and your sample is medium, then you would expect to reject the null hypothesis. If for some reason your formal null hypothesis test indicates otherwise, then you need to double-check your computations and interpretations. A second reason is that the ability to make this kind of intuitive judgment is an indication that you understand the basic logic of this approach in addition to being able to do the computations.

Statistical Significance Versus Practical Significance

Table 13.1 illustrates another extremely important point. A statistically significant result is not necessarily a strong one. Even a very weak result can be statistically significant if it is based on a large enough sample. This is closely related to Janet Shibley Hyde’s argument about sex differences (Hyde, 2007) [3] . The differences between women and men in mathematical problem solving and leadership ability are statistically significant. But the word significant can cause people to interpret these differences as strong and important—perhaps even important enough to influence the college courses they take or even who they vote for. As we have seen, however, these statistically significant differences are actually quite weak—perhaps even “trivial.”

This is why it is important to distinguish between the statistical significance of a result and the practical significance of that result. Practical significance refers to the importance or usefulness of the result in some real-world context. Many sex differences are statistically significant—and may even be interesting for purely scientific reasons—but they are not practically significant. In clinical practice, this same concept is often referred to as “clinical significance.” For example, a study on a new treatment for social phobia might show that it produces a statistically significant positive effect. Yet this effect still might not be strong enough to justify the time, effort, and other costs of putting it into practice—especially if easier and cheaper treatments that work almost as well already exist. Although statistically significant, this result would be said to lack practical or clinical significance.

Image Description

“Null Hypothesis” long description: A comic depicting a man and a woman talking in the foreground. In the background is a child working at a desk. The man says to the woman, “I can’t believe schools are still teaching kids about the null hypothesis. I remember reading a big study that conclusively disproved it years ago.” [Return to “Null Hypothesis”]

“Conditional Risk” long description: A comic depicting two hikers beside a tree during a thunderstorm. A bolt of lightning goes “crack” in the dark sky as thunder booms. One of the hikers says, “Whoa! We should get inside!” The other hiker says, “It’s okay! Lightning only kills about 45 Americans a year, so the chances of dying are only one in 7,000,000. Let’s go on!” The comic’s caption says, “The annual death rate among people who know that statistic is one in six.” [Return to “Conditional Risk”]

Media Attributions

- Null Hypothesis by XKCD CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial)

- Conditional Risk by XKCD CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial)

- Lakens, D. (2017, December 25). About p -values: Understanding common misconceptions. [Blog post] Retrieved from https://correlaid.org/en/blog/understand-p-values/ ↵

- Cohen, J. (1994). The world is round: p < .05. American Psychologist, 49 , 997–1003. ↵

- Hyde, J. S. (2007). New directions in the study of gender similarities and differences. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16 , 259–263. ↵

Descriptive data that involves measuring one or more variables in a sample and computing descriptive summary data (e.g., means, correlation coefficients) for those variables.

Corresponding values in the population.

The random variability in a statistic from sample to sample.

A formal approach to deciding between two interpretations of a statistical relationship in a sample.

The idea that there is no relationship in the population and that the relationship in the sample reflects only sampling error (often symbolized H0 and read as “H-zero”).

An alternative to the null hypothesis (often symbolized as H1), this hypothesis proposes that there is a relationship in the population and that the relationship in the sample reflects this relationship in the population.

A decision made by researchers using null hypothesis testing which occurs when the sample relationship would be extremely unlikely.

A decision made by researchers in null hypothesis testing which occurs when the sample relationship would not be extremely unlikely.

The probability of obtaining the sample result or a more extreme result if the null hypothesis were true.

The criterion that shows how low a p-value should be before the sample result is considered unlikely enough to reject the null hypothesis (Usually set to .05).

An effect that is unlikely due to random chance and therefore likely represents a real effect in the population.

Refers to the importance or usefulness of the result in some real-world context.

Research Methods in Psychology Copyright © 2019 by Rajiv S. Jhangiani, I-Chant A. Chiang, Carrie Cuttler, & Dana C. Leighton is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Null Hypothesis Definition and Examples

PM Images / Getty Images

- Chemical Laws

- Periodic Table

- Projects & Experiments

- Scientific Method

- Biochemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Medical Chemistry

- Chemistry In Everyday Life

- Famous Chemists

- Activities for Kids

- Abbreviations & Acronyms

- Weather & Climate

- Ph.D., Biomedical Sciences, University of Tennessee at Knoxville

- B.A., Physics and Mathematics, Hastings College

In a scientific experiment, the null hypothesis is the proposition that there is no effect or no relationship between phenomena or populations. If the null hypothesis is true, any observed difference in phenomena or populations would be due to sampling error (random chance) or experimental error. The null hypothesis is useful because it can be tested and found to be false, which then implies that there is a relationship between the observed data. It may be easier to think of it as a nullifiable hypothesis or one that the researcher seeks to nullify. The null hypothesis is also known as the H 0, or no-difference hypothesis.

The alternate hypothesis, H A or H 1 , proposes that observations are influenced by a non-random factor. In an experiment, the alternate hypothesis suggests that the experimental or independent variable has an effect on the dependent variable .

How to State a Null Hypothesis

There are two ways to state a null hypothesis. One is to state it as a declarative sentence, and the other is to present it as a mathematical statement.

For example, say a researcher suspects that exercise is correlated to weight loss, assuming diet remains unchanged. The average length of time to achieve a certain amount of weight loss is six weeks when a person works out five times a week. The researcher wants to test whether weight loss takes longer to occur if the number of workouts is reduced to three times a week.

The first step to writing the null hypothesis is to find the (alternate) hypothesis. In a word problem like this, you're looking for what you expect to be the outcome of the experiment. In this case, the hypothesis is "I expect weight loss to take longer than six weeks."

This can be written mathematically as: H 1 : μ > 6

In this example, μ is the average.

Now, the null hypothesis is what you expect if this hypothesis does not happen. In this case, if weight loss isn't achieved in greater than six weeks, then it must occur at a time equal to or less than six weeks. This can be written mathematically as:

H 0 : μ ≤ 6

The other way to state the null hypothesis is to make no assumption about the outcome of the experiment. In this case, the null hypothesis is simply that the treatment or change will have no effect on the outcome of the experiment. For this example, it would be that reducing the number of workouts would not affect the time needed to achieve weight loss:

H 0 : μ = 6

Null Hypothesis Examples

"Hyperactivity is unrelated to eating sugar " is an example of a null hypothesis. If the hypothesis is tested and found to be false, using statistics, then a connection between hyperactivity and sugar ingestion may be indicated. A significance test is the most common statistical test used to establish confidence in a null hypothesis.

Another example of a null hypothesis is "Plant growth rate is unaffected by the presence of cadmium in the soil ." A researcher could test the hypothesis by measuring the growth rate of plants grown in a medium lacking cadmium, compared with the growth rate of plants grown in mediums containing different amounts of cadmium. Disproving the null hypothesis would set the groundwork for further research into the effects of different concentrations of the element in soil.

Why Test a Null Hypothesis?

You may be wondering why you would want to test a hypothesis just to find it false. Why not just test an alternate hypothesis and find it true? The short answer is that it is part of the scientific method. In science, propositions are not explicitly "proven." Rather, science uses math to determine the probability that a statement is true or false. It turns out it's much easier to disprove a hypothesis than to positively prove one. Also, while the null hypothesis may be simply stated, there's a good chance the alternate hypothesis is incorrect.

For example, if your null hypothesis is that plant growth is unaffected by duration of sunlight, you could state the alternate hypothesis in several different ways. Some of these statements might be incorrect. You could say plants are harmed by more than 12 hours of sunlight or that plants need at least three hours of sunlight, etc. There are clear exceptions to those alternate hypotheses, so if you test the wrong plants, you could reach the wrong conclusion. The null hypothesis is a general statement that can be used to develop an alternate hypothesis, which may or may not be correct.

- Kelvin Temperature Scale Definition

- Independent Variable Definition and Examples

- Theory Definition in Science

- Hypothesis Definition (Science)

- de Broglie Equation Definition

- Law of Combining Volumes Definition

- Chemical Definition

- Pure Substance Definition in Chemistry

- Acid Definition and Examples

- Extensive Property Definition (Chemistry)

- Radiation Definition and Examples

- Valence Definition in Chemistry

- Atomic Solid Definition

- Weak Base Definition and Examples

- Oxidation Definition and Example in Chemistry

- Definition of Binary Compound

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Null and Alternative Hypotheses | Definitions & Examples

Null & Alternative Hypotheses | Definitions, Templates & Examples

Published on May 6, 2022 by Shaun Turney . Revised on June 22, 2023.

The null and alternative hypotheses are two competing claims that researchers weigh evidence for and against using a statistical test :

- Null hypothesis ( H 0 ): There’s no effect in the population .

- Alternative hypothesis ( H a or H 1 ) : There’s an effect in the population.

Table of contents

Answering your research question with hypotheses, what is a null hypothesis, what is an alternative hypothesis, similarities and differences between null and alternative hypotheses, how to write null and alternative hypotheses, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions.

The null and alternative hypotheses offer competing answers to your research question . When the research question asks “Does the independent variable affect the dependent variable?”:

- The null hypothesis ( H 0 ) answers “No, there’s no effect in the population.”

- The alternative hypothesis ( H a ) answers “Yes, there is an effect in the population.”

The null and alternative are always claims about the population. That’s because the goal of hypothesis testing is to make inferences about a population based on a sample . Often, we infer whether there’s an effect in the population by looking at differences between groups or relationships between variables in the sample. It’s critical for your research to write strong hypotheses .

You can use a statistical test to decide whether the evidence favors the null or alternative hypothesis. Each type of statistical test comes with a specific way of phrasing the null and alternative hypothesis. However, the hypotheses can also be phrased in a general way that applies to any test.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

The null hypothesis is the claim that there’s no effect in the population.

If the sample provides enough evidence against the claim that there’s no effect in the population ( p ≤ α), then we can reject the null hypothesis . Otherwise, we fail to reject the null hypothesis.

Although “fail to reject” may sound awkward, it’s the only wording that statisticians accept . Be careful not to say you “prove” or “accept” the null hypothesis.

Null hypotheses often include phrases such as “no effect,” “no difference,” or “no relationship.” When written in mathematical terms, they always include an equality (usually =, but sometimes ≥ or ≤).

You can never know with complete certainty whether there is an effect in the population. Some percentage of the time, your inference about the population will be incorrect. When you incorrectly reject the null hypothesis, it’s called a type I error . When you incorrectly fail to reject it, it’s a type II error.

Examples of null hypotheses

The table below gives examples of research questions and null hypotheses. There’s always more than one way to answer a research question, but these null hypotheses can help you get started.

| ( ) | ||

| Does tooth flossing affect the number of cavities? | Tooth flossing has on the number of cavities. | test: The mean number of cavities per person does not differ between the flossing group (µ ) and the non-flossing group (µ ) in the population; µ = µ . |

| Does the amount of text highlighted in the textbook affect exam scores? | The amount of text highlighted in the textbook has on exam scores. | : There is no relationship between the amount of text highlighted and exam scores in the population; β = 0. |

| Does daily meditation decrease the incidence of depression? | Daily meditation the incidence of depression.* | test: The proportion of people with depression in the daily-meditation group ( ) is greater than or equal to the no-meditation group ( ) in the population; ≥ . |

*Note that some researchers prefer to always write the null hypothesis in terms of “no effect” and “=”. It would be fine to say that daily meditation has no effect on the incidence of depression and p 1 = p 2 .

The alternative hypothesis ( H a ) is the other answer to your research question . It claims that there’s an effect in the population.

Often, your alternative hypothesis is the same as your research hypothesis. In other words, it’s the claim that you expect or hope will be true.

The alternative hypothesis is the complement to the null hypothesis. Null and alternative hypotheses are exhaustive, meaning that together they cover every possible outcome. They are also mutually exclusive, meaning that only one can be true at a time.

Alternative hypotheses often include phrases such as “an effect,” “a difference,” or “a relationship.” When alternative hypotheses are written in mathematical terms, they always include an inequality (usually ≠, but sometimes < or >). As with null hypotheses, there are many acceptable ways to phrase an alternative hypothesis.

Examples of alternative hypotheses

The table below gives examples of research questions and alternative hypotheses to help you get started with formulating your own.