- Undergraduate

- High School

- Architecture

- American History

- Asian History

- Antique Literature

- American Literature

- Asian Literature

- Classic English Literature

- World Literature

- Creative Writing

- Linguistics

- Criminal Justice

- Legal Issues

- Anthropology

- Archaeology

- Political Science

- World Affairs

- African-American Studies

- East European Studies

- Latin-American Studies

- Native-American Studies

- West European Studies

- Family and Consumer Science

- Social Issues

- Women and Gender Studies

- Social Work

- Natural Sciences

- Pharmacology

- Earth science

- Agriculture

- Agricultural Studies

- Computer Science

- IT Management

- Mathematics

- Investments

- Engineering and Technology

- Engineering

- Aeronautics

- Medicine and Health

- Alternative Medicine

- Communications and Media

- Advertising

- Communication Strategies

- Public Relations

- Educational Theories

- Teacher's Career

- Chicago/Turabian

- Company Analysis

- Education Theories

- Shakespeare

- Canadian Studies

- Food Safety

- Relation of Global Warming and Extreme Weather Condition

- Movie Review

- Admission Essay

- Annotated Bibliography

- Application Essay

- Article Critique

- Article Review

- Article Writing

- Book Review

- Business Plan

- Business Proposal

- Capstone Project

- Cover Letter

- Creative Essay

- Dissertation

- Dissertation - Abstract

- Dissertation - Conclusion

- Dissertation - Discussion

- Dissertation - Hypothesis

- Dissertation - Introduction

- Dissertation - Literature

- Dissertation - Methodology

- Dissertation - Results

- GCSE Coursework

- Grant Proposal

- Marketing Plan

- Multiple Choice Quiz

- Personal Statement

- Power Point Presentation

- Power Point Presentation With Speaker Notes

- Questionnaire

- Reaction Paper

- Research Paper

- Research Proposal

- SWOT analysis

- Thesis Paper

- Online Quiz

- Literature Review

- Movie Analysis

- Statistics problem

- Math Problem

- All papers examples

- How It Works

- Money Back Policy

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- We Are Hiring

Culture and Cultural Safety, Essay Example

Pages: 19

Words: 5223

Hire a Writer for Custom Essay

Use 10% Off Discount: "custom10" in 1 Click 👇

You are free to use it as an inspiration or a source for your own work.

Regarding the pivotal aspects of nursing, we need to mention that it includes the prevention of disease and the treatment of the patients; what is more, it also includes the promotion of healthy lifestyle. It is obvious that caring emerged to be fully interwined with the principles of nursing. Analyzing the philosophy of nursing, one can easily see that this occupation mainly requires the respect towards all the ill, not making emphasis on certain categories of people; the thing is that when you are treating the patients, it means that the key goal that you need to follow must be the one based on your undeniable craving to satisfy the patients with the qualified help. The nature of nursing has much in common with both medicine and scientific expertness. The major task is to heal the sick by preventing the disease. It is necessary to take into account the fact that since the profession of nursing is the one, going through endless process of evolving, nurses are required to be also interested in applying new practices while treating the patients. As a result, one can come to understanding that nursing is an everlasting process of studying and enrichment in new branches of knowledge.

Considering the issue of nursing, one cannot skip with the importance of cultural security as well. It is clear that cultural security emerges to be one of the most significant components within the field of nursing in New Zealand. The construct of the aforementioned issue lies in directing nursing area as ‘safe’ and ‘effective’ for the customer or family/ whanau from dissimilar culture (Richardson & MacGibbon, 2010). Obviously, cultural safety occurs as “the effective nursing practice of a person or family from another culture, and is determined by that person or family. Culture includes, but is not restricted to, age or generation; gender; sexual orientation; occupation and socioeconomic position; ethnic descent or migrant awareness; religious or spiritual belief; and disability” (Nursing Council of New Zealand [NCNZ], 2011, p.7). Apart from the above-said, cultural safety distinguishes achievement of positive health results via reorganizing the health status of New Zealanders as well as acknowledging the values, beliefs and practices of those having various cultural backgrounds (Wepa, 2004). In accordance with NCNZ (2011), any care offered by nurses that disregards and humiliates the cultural identity of an individual appears to be culturally improper act.

The major goal behind cultural security lies in improving the health status of New Zealanders; moreover, developing the provision of health and disability services by so-called culturally safe nursing workforce. On the basis of cultural safety norms, there has to be trusting negotiations between a nurse and the patient; in addition, a nurse has to demonstrate the power contacts between a nurse and the patients (NCNZ, 2011). It is worth accepting ethnicity based disparities, so that an unfair practice can be minimized. In New Zealand, the policy of Treaty of Waitangi is utilized to negotiations between Mâori and Pakeha, as well to other national minorities. The number of health disparities among the Maori people is mostly related to shortage of availability of culturally adequate health care services (Ren, 2009). To offer culturally secure treatment to people from various cultures, in contemporary nursing field health professionals tend to take into account three pivotal norms of the Treaty of Waitangi, which are relationship, participation and defence (Kingi, 2007).

Relationship occurs as cooperating together with the customer and certain community in order to improve positive health outcomes (MidCentral District Health Board [MDHB], 2008). To be precise, it is worth saying that in partnership the customers are obliged to provide informed decisions and they are also engaged in all the processes which refer to their health, disease, and care. A peculiar thing is that it is not just about engaging patients in making their choices so as to provide an anticipated decision. Being involved in partnership incorporates providing the information to patients, which is vivid and adequate in a way they are likely to understand, so they are able to make an informed choice with regards to their treatment and care as well give some questions. Trusted relationship appears when people’s problems and likes are heard and answered (NCNZ, 2012a).

Participation engages the patients in decision making process, projecting and provision of health and disability services (MDHB, 2008). Active participation of health consumers appears to be important to improve the patient’s insight as well as satisfaction with provided nursing treatment, contributing to advanced care outcomes and improvement of their health state (Sahlsten, Larsson, Sjostrom, Lindencrona and Plos, 2007). For qualified culturally safe nursing treatment and to match patient preferences, it is important for nurses to become aware of the patient’s attitude towards the issue of participation (Larsson, Sahlsten, Sjostrom, Lindencrona & Plos, 2007). Sufficient and obvious information provided by a nurse enhances the active participation of health consumers, whereas the shortage of knowledge results in obstructions to active participation (Florin, 2007).

In protection, it is significant for nurses to provide their services in a manner that appreciates and protects cultural constructs, values and principles of patients from another cultural environment (MDHB, 2008). It is also extremely vital to defend patients’ privacy, since it is likely to build the trusting relationship between them and health care experts and the patients. Privacy/confidentiality policy is not only about health records; it also applies to all other individually recognisable health data, including genetic information, clinical survey and treatment records, mental health disorder treatment notifications ,suicide notes, terminally diseased notes, patient’ personal data and also the protection of cultural beliefs. This information has to be accessible to nurses who are directly responsible for looking after the health consumers (NCNZ, 2011). To provide culturally safe treatment, health professionals are obliged to protect patients’ rights and privacy. This is the ethical and legal accountability of health care experts (NCNZ, 2011).

In the given scenario, three items which inhibit the provision of nursing care are breach of privacy and confidentiality, horizontal outrage and discrimination against and disrespect towards the health consumers. These three items are an integral part of culturally unsafe tendency, since they are ignoring the patient’s rights. “Unsafe cultural practice comprises any action which diminishes, demeans or disempowers the cultural identity and well-being of an individual” (NCNZ, 2011, p.7).

The breach of privacy of the patient’s individual details and confidentiality appears to be the most significant dimension that is impacting the delivery of proficient nursing treatment in the given scenario. The nurses are loudly advancing the arguments about their right to reject to look after a patient who, for instance, has history of sexual abuse offence. As the health consumer is directly across from the nurse’s station, there is a definite probability that he heard the communication. Also there is a possibility that other patients, attendants and allied staff participants overheard the conversation, breaching the patient’s confidentiality. In accordance with the Code of Conduct for nurses, principle five (NCNZ, 2012b), it is the duty of health professionals to defend the privacy of health consumers’ personal information. Any information related to a patient should be utilized for professional aims only. Nurses should tell the health consumers if there is need to unravel the information to other health team departments, and obtain informed consent from the patient to uncover that information. However, in case there is any serious risk to the health consumer or public safety, a decision can be made without the patient’s consent. Health consumers’ personal information or health records should be preserved securely and only accessed for the purpose of providing treatment or any legal aspects. Nurses do not have to discuss practice issues in public such as, for example, social media in order to maintain health consumers’ confidentiality and privacy. Despite the fact that the name of a health consumer might be unrevealed, still they could be identified (NCNZ, 2012b).

The nurse-patient negotiations appear to be the most important part of nursing concept. The construct of trust is one of the most significant components in the nurse-patient negotiations. It can be easily figured out as well as easily broken. A trusting nurse-patient partnership apparently depends on communication. Health consumers may like to share their problems with a health professional and may see the nurse as someone who will not judge them and unveil their personal stories with some other people. If the expectations of the patient are not answered by the health professionals, and the health consumer indicates that their information is disclosed to other members of the personnel patient’s trust along with the relationship will be broken once and for all time. On the other hand, the increase of trust partnership between patients and nurses will modify the image of nurses in society as a positive element (Said, 2013). As a result, nurses should not uncover information unless it is mandatory, such as legally or for patient care.

Another issue that is influencing professional nursing treatment in this scenario is discrimination and disregard of a patient. According to the initial principle of the Code of Conduct for nurses, health professionals should respect the dignity and individuality of health consumers (NCNZ, 2012b). This constituent vividly states that nurses should practise in a way that respect and does not discriminate against any patient from any culture, age, gender, sexual orientation and political opinion (NCNZ, 2012b). In this scenario, nurses are discriminating against the patient because he has history of sexual abuse offences. They did not think of the patient’ self-respect and about making a therapeutic relationship with him. They do not support a principle of professionalism, since they are failing to provide culturally safe care by disregarding the health consumers, as they may have overheard the conversation. Health professionals are being judgemental and unwilling to offer nursing care for these patients in the scenario, which may result in the patients’ neglect. It is the accountability of health professionals to look after the patients not showing any signs of discrimination or label (NCNZ, 2012b). Moreover, all nurses are obliged to abide standards of moral relationship and ethics, and have to be non-judgemental (New Zealand Nurses Organisation [NZNO], 2010).

The third aspect that is inhibiting the provision of professional nursing treatment in this scenario is horizontal outrage towards a new graduate nurse by instigating her not to look after the patient. Horizontal outrage originates a negative work atmosphere impairing teamwork and compromising health consumers’ care (Araujo & Sofield, 2011). Horizontal outrage occurs as any unwanted abuse, assaultive and harmful behaviour by a health rofessional or a team of nurses toward a colleague via assaultive viewpoints, actions and sayings within the workplace (Becher & Visovsky, 2012).

In this scenario, senior health professionals are demonstrating a kind of bullying as they pressurised the new graduate nurse to accept the choices of the other nurses. As a new graduate nurse, I may consider senior nurses to limit my rights to voice my attitude towards this issue In view of Kelly and Tazbir, 2013, peer pressure is one of workplace bullying divisions which is likely to compromise health consumers’ care. I am likely to feel fear, and anxiety in this case and I must agree with my senior colleagues’ ideas as I would not want to be an outcast within a new workplace. A feeling of fear, concern and separation can result in emotional disorders, which later lead to poor attentiveness and fallacies. On this phase, I am likely to ruin patient’s security. Workplace bullying results in stress, hazardous culturally nursing actions and improper partnership with health consumers and team members (Yildrim, 2009). In accordance with the Code of Conduct’s sixth principle, health professionals have to work honestly with colleagues and in a co-operative way in order to match health consumers’ requirements (NCNZ, 2012b).

Health professionals have to be capable of showing their skills and judgement to cope with professional, lawful and ethical accountabilities dimensions and competent enough to recognize an atmosphere that is culturally tolerant in respect of health consumers (NCNZ, 2012c). After what took place in the scenario, being a registered health professional, I figured out that senior nurses maintain improper nursing acts that are not culturally hazardous for health consumers and the nurses. They are breaching the confidentiality and disregarding the health consumers. What is more, there is also horizontal outrage towards a new nurse as senior nurses encourage her to maintain their choices. In such a case, I have accountability as a registered nurse to follow professional principles of nursing practice in order to provide the patients’ safety.

The senior health professionals are violating the confidentiality of the patient’s individual data. They are rejecting to provide health care services for a health consumer who possesses history of sexual abuse offences. The health professionals are obliged to defend and honour the confidentiality of health consumers’ individual information especially about sensitive issues (Privacy commissioner, 2008). In such a case, initially I will shut the door as a health consumer is close to the nursing station. Furthermore, I will tell the health professionals about this, since health consumers are likely to expect that their information will not be shared with the other people. During treatment period, health professionals reassure the health consumer that their information will be protected (NCNZ, 2012b). By loudly communicating about the health consumer’s criminal history, health professionals are breaching the norms of trust. What is more, I will care for this health consumer by obeying professional principles of nursing practice and reassure patient’s security and quality treatment. Evidently, there is high probability that other health consumers, allied personnel and attendant are likely to have overheard the communication. They emerge to be likely to start disrespecting the health consumer that compromises the patient’s safety, respectively. It is the accountability of health professionals to indicate, inform and deal with the cases that impact health consumer and the members of personnel (NCNZ, 2012c) Nurses are responsible for their practice as well as the choices so they have to perform ethically (NCNZ, 2012c).

In the scenario, health professionals are also humiliating and disregarding the health consumer, since they are thought to be involved in sexual abuse offences. It appears to be the right of the health consumer to be treated with respect; the patient also has the right to complain (Health and Disability Commissioner [HDC], 2009). In such a case, as I am aware that health consumer may have heard the communication. I will provide him with an opportunity to fill a complaint form in case he/she wants; I will also fill the incident form and inform to the charge health professional, since it is compulsory to take some measures. Health professionals have to figure out the legal aspects in the practice and report on this matter to the appropriate people. Health professionals must serve in accordance with relevant legislation/norms/principles and follow health consumers’ rights (NCNZ, 2012c). Disregard/humiliation in respect of the health consumer by health care personnel is very vexing for the health consumer. It is a threat to health consumers’ security and health, since it inhibits patient’s agreement with health care. Usually, people like to commit suicides in case they have low self-esteem; this factor emerges to be extremely depressing for them. It is so destructive for health consumers and their family (Leape, Shore & Dienstag, 2012). Consequently, it is my accountability as a registered health professional to keep health consumers safe by looking after them.

In the given scenario, I have to keep myself safe from horizontal outrage from senior health professionals. Horizontal outrage is likely to result in depression, fear and seriously lowered self-esteem that will lead to poor nursing practice and interpersonal negotiations (Longo, 2010). First of all, I will follow my accountabilities in accordance with lawful and ethical limits by recognizing health consumers’ rights as well providing culturally safe treatment to them. I will also report it as at the earliest convenience after the incident took place. Health professionals have to keep clear and straightforward notes, any entries in health consumers’ notes have to be mentioned, dated and timed. Health consumers are obliged to make certain that all health consumers’ notes are preserved securely for their confidentiality (NCNZ, 2012 b). Being a registered health professional, I should be conscious about my rights, practices and principles of hospital for workplace bullying for my safety, and to master the ability to deal with these cases. Health professionals have to become aware about the workplace protocols in order to manage the issue of outrage acts and keep themselves safe, respectively (Murray, 2009). What is more, I will request help and explanation from the charge health professional and nurse instructor. I will also fill an incidence form on horizontal outrage. It is extremely significant to report incident to charge health professional (Longo, 2010).

The workplace principles in healthcare system appear to the matter of great importance for individual-centred clinically efficient treatment, whereas, an improper workplace atmosphere results in dramatic impact on the health situation (Manley, Sanders, Cardiff & Webster, 2011). The alterations I would be eager to initiate are preventing horizontal outrage, embodying inter-professional cooperation and advanced performance. To deliver these modifications in workplace environment, I chose Kurt Lewin management approach.

The Kurt Lewin’s management model consists of three phases, which are unfreezing, moving and refreezing (Mclean, 2011). In the first phase of modification (unfreezing), a problem is indicated and measures are prepared in order to accept that alteration. This very phase also encloses breaking the current approaches to working before constructing a new principle of performance (Mcgarry, Cashin & Fowler, 2012). The further phase is the process in which modification is embodied (Huber, 2014). It is important in this process to be sure that new methods of practising can provide more positive results than the existing ways (Chang & Daly, 2012). The final phase (refreezing) is utilized for evaluation of new modifications for its efficacy (Sutherland, 2013).

The first change I am eager to make is how to avoid horizontal outrage. Horizontal outrage, or destructive behaviours between nursing personnel, can result in enormous harm to health consumers and the personnel security as well as wellbeing (Longo, 2010). In the scenario, I think that senior health professionals make me accept their decisions and they are not permitting me to encapsulate my attitude towards particular issues; obviously, it is bullying. In the unfreezing stage, new graduate health professionals have to be aware of zero tolerance principles on bullying (Sayre, 2010). Each individual possesses the right to have a workplace that is fair; each person has the right to be treated with some reverence (NCNZ, 2012c). The clinical manager has a significant role to create a harmonious atmosphere which is based on a high level of proficiency with no signs of no bullying (Cleary, Hunt, Walter & Robertson, 2009). The moving stage is the embodiment of the project, so in this stage, personnel will be taught about strict zero tolerance principles in the workplace environment and the significance of teamwork, which is likely to lead to gradual prevention of horizontal outrage and confusions (Ekici & Beder, 2014). Health professionals have to be educated how to preserve regard and dignity of other members of the personnel taking into consideration culture distinctions (Rocker, 2008). During the refreezing phase, management and health professionals have to estimate the efficacy of rearrangement (Sayre, 2010). It is extremely significant to become aware of whether the modifications have either positive or negative influence (Clarkson, Flores, Johnson & Lonadier, 2012).

The second transformation would be the embodiment of inter-professional cooperation. Efficient inter-professional partnership is an integral element of nursing. It is the cooperation between the members of personnel, health consumers and their families in an honest and accountable way. This facilitates the process of building trust amongst the health consumers (Barwell, Arnold & Berry, 2013). Efficient cooperation between health professionals care personnel is vital for health consumers’ safety and person-centered treatment. As a result, they can express their viewpoints about patient’s health state, care options for necessary health outcomes (Nadzam, 2009). In this scenario, instead of supporting professional cooperation, health professionals are loudly discussing the reluctance to look after the health consumers. To provide quality treatment that is patient-cantered and culturally adequate, health professionals have to take into account the issue of professional negotiations (Arnold & Boggs, 2011).

In the initial stage of Lewin’s change management model, health professionals have to be addressed by responsible nurse or clinical manager concerning their improper cooperation that is worth being improved. Within the moving stage, unprofessional cooperation can be settled on a solution by ongoing teaching policies. The hospital principles also facilitate the process of health professionals’ understanding of the need to cooperate, since one of the reasons behind inappropriate language is the shortage of professional skills (Wachtel, 2011). During the refreezing process, health professionals will assess their learning from teaching projects and keep obeying the guidelines of the nursing practice. Positive cooperation impacts the efficacy of health consumers’ treatment and makes the performance of the teamwork much better (Sully & Dallas, 2010).

The third amendment would be efficient teamwork, since it possesses a critical factor in nursing practice (West, 2012). Effectual teamwork is important for the highly qualified and safe health consumers’ treatment. It makes nursing practice more efficient and improves final outcomes. Moreover, it helps the personnel to become aware of their peers (Ward, 2013). In this scenario, I come to understanding that there is no maintenance and co-operation between health professionals; they cannot come to mutual agreement. In the unfreezing stage, health professionals have to master the significance of understanding, cooperation with each other. Formal education projects are likely to assist in learning the way of collaboration in the workplace. Health professionals are obligated to become aware of the way how the shortage of teamwork between the staff members can lead to a negative influence on health consumers (Barwell et al., 2013). In the moving stage, health professionals will pass ongoing teaching programmed based on effectual teamwork. In the final stage, health professionals will estimate their awareness of the programmer.

The factors showing my nursing practice are cultural expertise, person-centered clinical supervision, health consumers’ feedback and the utilization of the the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi. Clinical monitoring occurs as very helpful for health professionals in proficient maintenance as well as learning how to become accountable for their individual performance. Clinical inspection is regarded as one of the best methods helping new graduate health professionals in offering culturally risk-free nursing treatment to health consumers (Rassool, 2008). Their performance can be closely inspected by a clinical manager who can recommend the junior personnel whether the treatment offered was culturally harmless or not (Hole, 2009). In other words, to reach culturally secure treatment in nursing practice, any comments, viewpoints, and assumptions from a clinical inspector are very useful (Chang & Daly, 2012). Being a new graduate health professional, I will request feedback and some comments from a clinical inspector in order to find out whether I provide culturally risk-free practice or not; these feedbacks are likely to help me rearrange my future performance. Clinical inspection emerges to be very important and for the nurses (Dawson, Phillips & Legget, 2012); it is likely to help junior personnel to undergo various problems whilst practicing as well (Lynch, Hancox, Happel, & Parker, 2009).

Feedback from health consumers is really helpful to the health professionals to assess the treatment offered. In accordance with NCNZ (2012c), expertises (1.5 and 2.6), efficacy of nursing care can be evaluated on the basis of health consumers’ feedback, since it is not the health professionals, or team members, it is the customer who receives the treatment (McMurray & Clendon, 2010). Thus, I will request feedback and comments from my clients to make certain that the treatment I offer was actually culturally secure. Once health consumers cannot provide feedback, I will ask another family member to answer my request. I will also provide therapeutic partnership with health consumers. Good collaboration and trust are extremely significant when building an effective therapeutic communication (Richard & Tabatha, 2010).

To assure culturally secure practice and patient-centered treatment, the awareness of the three principles of Treaty of Waitangi, which are partnership, participation and protection cannot be underestimated (NCNZ, 2011). Therefore, I will show these fundamental components during my nursing practice by constructing the cooperation with the health consumers and their family members; I will also demonstrate my striving to instigate them to take part in decision making process as well as care planning for successful health results. By accomplishing these steps, I will get to know their health and disease state in a more detailed way. For instance, I can find out if the clients are allergic to any remedy and. I will also take into consideration their rights of confidentiality, regard, reported consent and informed decisions. Moreover, I will ensure the health consumers that I follow the privacy and confidentiality principles. I will honour their values and beliefs. For instance, in some religions, meat is not permitted to eat; and if I ignore the patients’ traditions, I will demonstrate my disrespect. As a result, I need to be aware of the health consumers’ meals’ choices, pray peculiarities, clothing and other dimensions. I should esteem all cultures, customs, values and beliefs in order to provide highly-qualified nursing practice. All the aforementioned strategies are likely to assist in demonstrating that my practice occurs as culturally secure.

Naturally, the issue of discrimination in nursing is likely to affect both sexes, involving the unfair determination or decision making based on person’s gender as well as racial identity. Some modern scientists report that almost fifteen percent of patients suffer from discrimination while being treated by nurses. There exists the biased practice that different ethnicities are estimated in accordance with their viewpoints; moreover, the nurses tend to take into consideration the appearance of their patients, disregarding the norms ethics and human rights.

In conclusion, although the issue of discrimination in nursing is responded by the implementation of the number of anti-discrimination laws, it still can be faced in many today’s hospitals. This discrimination is typical of both sexes: males and females. The sex discrimination in nursing can be traumatic to human psyche. The person can be psychologically and emotionally destroyed when he or she is discriminated by the nurse. Apart from that, the sex as well as racial discrimination provides the misbalance within the nursing staff and usually results in unhealthy environment. The negative interaction between departments and the increased number of conflicts may contribute badly to the hospital performance. Despite the existence of gender and race discrimination in many hospitals, there should always be given adequate attention by means of regulatory laws. The point is that in case gender or race discrimination act happens, one should never leave it yet use the complete set of laws to support ourselves.

R eferences

Araujo, S., & Sofield, L. (2011). Workplace Violence in Nursing Today. The Nursing Clinics of North America, 46(4), 457-464.

Arnold, E., & Boggs, K. U. (2011). Interpersonal relationships: Professional communication skills for nurses (6th ed.). St Louis, MO: Saunders-Elsevier.

Barwell, J., Arnold, F., & Berry, H. (2013). How Interprofessional Learning Improves Care. Nursing Times, 10(21), 14-16.

Becher, J., & Visovsky, C. (2012). Horizontal Violence in Nursing. Medsurg Nursing , 21(4), 210-232.

Chang, E., & Daly, L. (2012). Transitions in Nursing: Preparing for Professional Practice . Chatswood, Australia: Elsevier.

Clarkson, L., Flores, A., Johnson, C., & Lonadier, R. (2012). Horizontal Violence in Nursing Affecting Nurse Retention. Retrieved from http://claudettejohnson.weebly.com/uploads/2/1/4/2/21425962/research_team_purple_week_8_paper-_final.pdf

Cleary, M., Hunt, G. E., Walter, G., & Robertson, M., (2009). Dealing with Bullying in the Workplace Towards Zero Tolerance. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing, 47(12), 34-41.

Dawson, M., Phillips, B., & Leggat, S. G. (2012). Effective Clinical Supervision for Regional Allied Health Professionals: The Supervisee’s Perspective. Australian Health Review, 36, 92–97.

Ekici, D., & Beder, A. (2014). The Effects of Workplace Bullying on Physicians and Nurses. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing, 31(4), 24-33.

Health and Disability Commissioner. (2009). The HDC Code of Health and Disability Services Consumers’ Rights Regulation 1996. Retrieved from http://www.hdc.org.nz/the-act–code/the-code-of-rights/the-code-(full)

Hole, J. (2009). The Newly Qualified Nurse’s Survival Guide (2nd ed.). Chichester, United Kingdom: Radcliffe publishing.

Huber, D. (2014). Leadership and Nursing care Management (5th ed.). St Loius, MO: Elsevier.

Kelly, P., & Tazbir, J. (2013). Essentials of Leadership and Management (3rd ed.) Sydney, Australia: Cengage Learning.

Kingi, T. R. (2007). The Treaty of Waitangi: A Framework for Maori health development. New Zealand Journal of Occupational Therapy , 54(1), 4-10.

Larsson, I. E., Sahlsten, M. J. M., Segesten, K., & Plos, K. A. E. (2011). Patients’ Perceptions of Nurses’ Behaviour That Influence Patient Participation in Nursing Care: A Critical Incident Study . Journal of Nursing Research and Practice , 1-8.

Leape, L. L., Shore, M. F., Dienstag, J. L., Mayer, R. J., Edgman-Levitan, S., Meyer, G. S., & Healy, G. B. (2012). Perspective: A Culture of Respect, part 1: The Nature and Causes of Disrespectful Behavior by Physicians. Academic Medicine, 87(7), 845-852.

Longo, J., (2010). Combating Disruptive Behaviors: Strategies to Promote a Healthy Work Environment. The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 15(1), 1.

Lynch, L., Hancox, L., Happel, B., Parker, J. (2009). Clinical Supervision for Nurses. Chichester, United Kingdom: Wiley Blackwell.

Manley, K., Sanders, K., Cardiff, S., & Webster, J. (2011). Effective Workplace Culture: The Attributes, Enabling Factors and Consequences of a New Concept. International Practice Development Journal , 1(2), 1-29.

Mcgarry, D., Cashin, A., & Fowler, C. (2012). Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing and the ‘Plastic Man’: Reflections on the Implementation of Change Drawing Insights from Lewin’s Theory of Planned Change. Contemporary Nurse, 41(2), 263-270.

Mclean, C., (2011). Change and Transition: What Is the Difference? British Journal of School Nursing , 6(2), 78-81.

McMurray, A., & Clendon, J. (2010). Community Health and Wellness: Primary Health care in Nursing. Sydney, Australia: Elsevier.

MidCentral District Health Board. (2014). Nursing Entry to Practice (NETP) programme handbook: Acute and specialty practice. Retrieved from http://www.midcentraldhb.govt.nz/WorkingMDHB/CareerInformation/Nursing/Documents/MCH_NETP_Learning_framework_2014.pdf

Murray, J. S. (2009). Workplace Bullying in Nursing: A Problem that Can’t Be Ignored. Medsurg Nursin g, 18(5), 273-276.

Nadzam, D. M. (2009). Nurses’ Role in Communication and Patient Safety. Journal of Nursing Care Quality , 24(3), 184-188.

Nursing Council of New Zealand. (2011). Guidelines for Cultural Safety, the Treaty of Waitangi, and Maori Health in Nursing Education and Practice. Wellington, New Zealand: Author.

Nursing Council of New Zealand. (2012a). Nursing Council of NZ’s Draft Code of Conduct. Wellington, New Zealand: Author.

Nursing Council of New Zealand. (2012b). Code of Conduct for Nurses. Wellington, New Zealand: Author.

Nursing Council of New Zealand. (2012c). Competencies for Registered Nurses. Wellington, New Zealand: Author.

New Zealand Nurses Organisation. (2010 ). Code of Ethics: Towards Improving Health Outcomes in New Zealand. Wellington, New Zealand: Author.

Privacy commissioner. (2008). Health Information Privacy Code 1994 . Retrieved from https://privacy.org.nz/assets/Files/Codes-of-Practice-materials/HIPC-1994-incl.-amendments-revised-commentary.pdf

Ren, X. (2009). Reaping the Benefits of a Treaty of Waitangi Workshop. Kai Tiaki Nursing New Zealand , 15(7), 28-29.

Richardson, F., & MacGibbon, L. (2010). Cultural safety: Nurses’ Accounts of Negotiating the Order of Things. Women’s Studies Journal , 24(2), 54-65.

Richard, P. L. & Tabatha, M. (2010). Fostering Therapeutic Nurse-Patient Relationships. Journal of Nursing , 8(3), 4-9.

Said, N. B. (2013 ). Nurse-Patient Trust Relationship . Retrieved from www.researchgate.net/…NursePatient_Trust_Relationship/…/0c9605162…

Sayre, M. M. (2010 ). Improving Collaboration and Patient Safety by Encouraging Nurse to Speak up: Overcoming Personal and Organisational Obstacles through Self-Reflection. Los Angeles, CA: UCLA.

Sully, P., & Dallas, J. (2010). Essential Communication Skills for Nursing and Midwifery. London, United Kingdom: Elsevier.

Sutherland, K. (2013). Applying Lewin’s Change Management Theory to the Implementation of Bar-Coded Medication Administration. Canadian Journal of Nursing Informatics, 8(1), 1-6.

Wachtel, L. P. (2011). Therapeutic Communication: Knowing What to Say When (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Ward, J. (2013). The Importance of Teamwork in Nursing.

West, M. A. (2012). Effective Teamwork: Practical Lessons from Organizational Research (3 rd ed.). Chichester, United Kingdom: BPS Blackwell.

Yildrim, D. (2009). Bullying among Nurses and Its Effects . International Nursing Review, 56,504-511.

Stuck with your Essay?

Get in touch with one of our experts for instant help!

Marjane’s Interaction With Western Culture, Essay Example

America: The New World in Transition, Essay Example

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free guarantee

Privacy guarantee

Secure checkout

Money back guarantee

Related Essay Samples & Examples

Voting as a civic responsibility, essay example.

Pages: 1

Words: 287

Utilitarianism and Its Applications, Essay Example

Words: 356

The Age-Related Changes of the Older Person, Essay Example

Pages: 2

Words: 448

The Problems ESOL Teachers Face, Essay Example

Pages: 8

Words: 2293

Should English Be the Primary Language? Essay Example

Pages: 4

Words: 999

The Term “Social Construction of Reality”, Essay Example

Words: 371

The Cultural Safety Concept: Gibbs’ Reflective Cycle Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

Description of the theory of cultural safety, distinguishing characteristics of cultural safety.

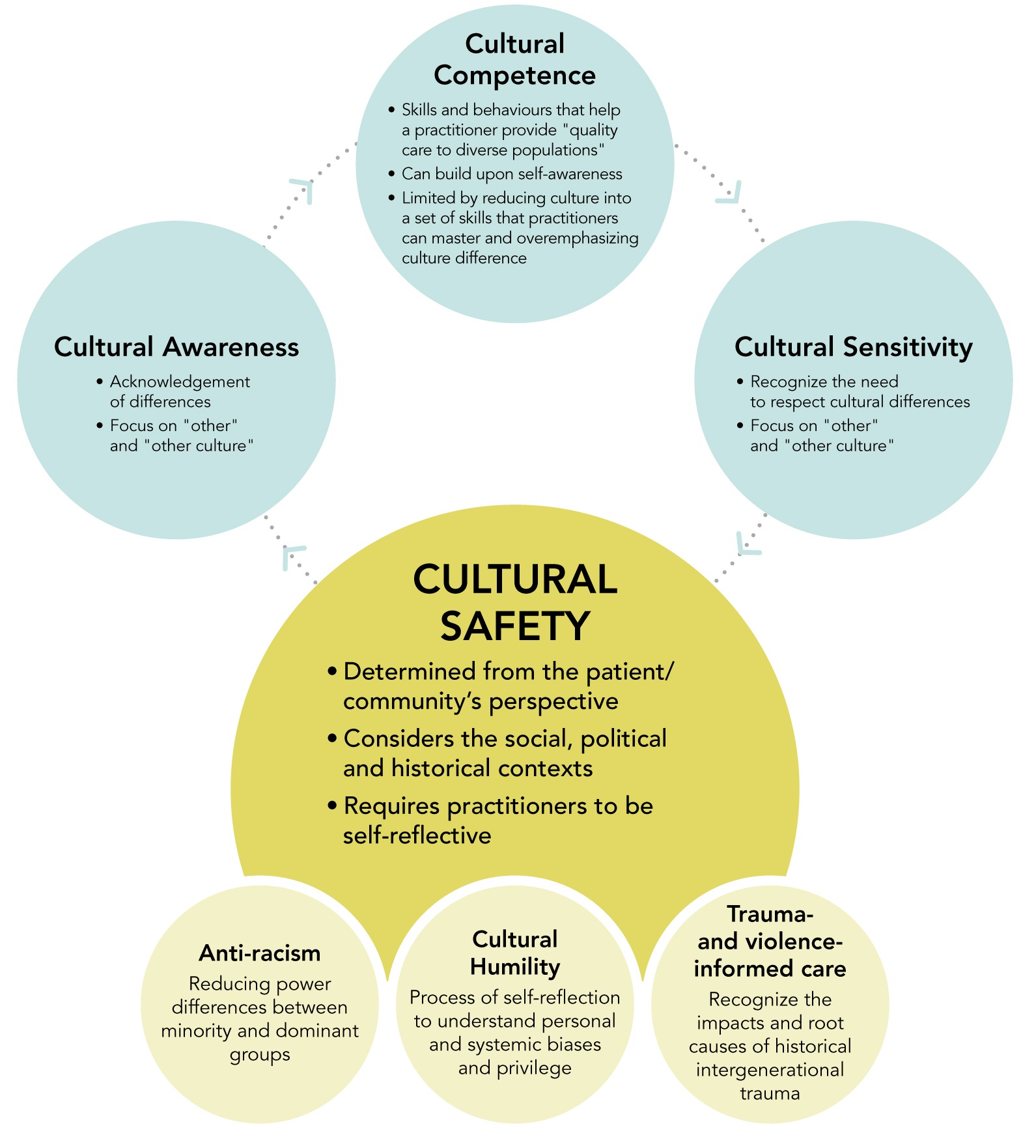

Cultural safety has a particularly important place for consideration in many spheres of human activity. This concept implies an awareness of the importance of culture in shaping individuals’ experiences of health and healthcare. In other words, it relies on the understanding that medical services should be provided with the cultural beliefs, values, and practices of various patients in mind. In addition, the concept of cultural safety implies taking into account the historical and modern context in which a particular community is located.

Particular importance should be given to the discussion of cultural safety’s three tenets. The first of these is the balance of power, which is based on the unequal distribution of authority between healthcare providers and patients. This is especially critical for those communities that are considered marginalized or oppressed. Within this aspect, cultural safety implies addressing this problem in healthcare and providing patients with the opportunity to be educated in the field of medical services (Curtis et al., 2019). Thus, they will be able to make informed decisions about their health on their own.

The second tenant becomes cultural humility, which implies the ability of medical professionals to realize the possible cultural biases that they have. The identification of these indicators will make it possible to provide the most comprehensive care to patients and strengthen diversity and inclusion in healthcare (Curtis et al., 2019). Moreover, it will help in creating a more open and respectful environment in the healthcare organization. The third tenant is anti-opposition, which draws attention to systemic opposition and discrimination (Curtis et al., 2019). The main negative effect of this aspect is the deterioration of conditions for receiving health services from marginalized communities. Cultural Security aims to continue work to counteract these negative effects. This initiative is represented through advocacy for policies and practices that promote equity and inclusion.

To gain a better understanding of what cultural security is, it is important to know how it differs from two more commonly used terms in the U.S.: cultural humility and cultural competence. These terms can often be confused due to the fact that they all relate to phenomena in healthcare such as diversity, equity, and inclusion. The leading difference between cultural security and cultural humility and cultural competence is that it focuses on creating an environment where patients from diverse cultural backgrounds and experiences feel safe and secure (Curtis et al., 2019). On the other hand, humanity and competence focus on the healthcare provider’s ability to be self-reflective and have the knowledge and skills to care for patients from different cultures effectively. Another difference in cultural security is the emphasis on issues that exist in society. It focuses on the systemic opposition and discrimination that marginalized communities experience in modern society. Thus, it makes an attempt to transform the healthcare system on a larger and global level.

In conclusion, cultural safety has a valuable place in the field of healthcare. This phenomenon contributes to the limitation of such negative consequences of marginalization and oppression of cultural minorities as discrimination and prejudice. This contributes to strengthening aspects such as diversity and inclusion, which have a critical role in expanding the availability of health services. In the work of nurses, cultural safety is necessary to ensure that all patients receive care that is respectful, equitable, and culturally responsive to their needs.

Curtis, E., Jones, R., Tipene-Leach, D., Walker, C., Loring, B., Paine, S. J., & Reid, P. (2019). Why cultural safety rather than cultural competency is required to achieve health equity: a literature review and recommended definition . International Journal for Equity in Health, 18 (1), 1-17. Web.

- Nursing: Caregivers of Elderly Patients

- Nursing Care Theories: Henderson’s Theory

- "The Epic of Gilgamesh" by Ryan Gibbs

- The Topic of Diagnostic Measures

- Ethos, Pathos and Logos in "The Exploitation" by Adam Rulli-Gibbs

- Psychological Concerns Among Oncology Nurses

- Innovative Changes in New Jersey's Nursing Program

- The Issue of the Medication Errors

- The Concept of Cultural Relativism in Nursing

- A Path to Achieve Health Equity

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, February 11). The Cultural Safety Concept: Gibbs' Reflective Cycle. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-cultural-safety-concept-gibbs-reflective-cycle/

"The Cultural Safety Concept: Gibbs' Reflective Cycle." IvyPanda , 11 Feb. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/the-cultural-safety-concept-gibbs-reflective-cycle/.

IvyPanda . (2024) 'The Cultural Safety Concept: Gibbs' Reflective Cycle'. 11 February.

IvyPanda . 2024. "The Cultural Safety Concept: Gibbs' Reflective Cycle." February 11, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-cultural-safety-concept-gibbs-reflective-cycle/.

1. IvyPanda . "The Cultural Safety Concept: Gibbs' Reflective Cycle." February 11, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-cultural-safety-concept-gibbs-reflective-cycle/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "The Cultural Safety Concept: Gibbs' Reflective Cycle." February 11, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-cultural-safety-concept-gibbs-reflective-cycle/.

- Open access

- Published: 14 November 2019

Why cultural safety rather than cultural competency is required to achieve health equity: a literature review and recommended definition

- Elana Curtis ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9957-7920 1 ,

- Rhys Jones 1 ,

- David Tipene-Leach 2 ,

- Curtis Walker 3 ,

- Belinda Loring 1 ,

- Sarah-Jane Paine 1 &

- Papaarangi Reid 1

International Journal for Equity in Health volume 18 , Article number: 174 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

373k Accesses

534 Citations

178 Altmetric

Metrics details

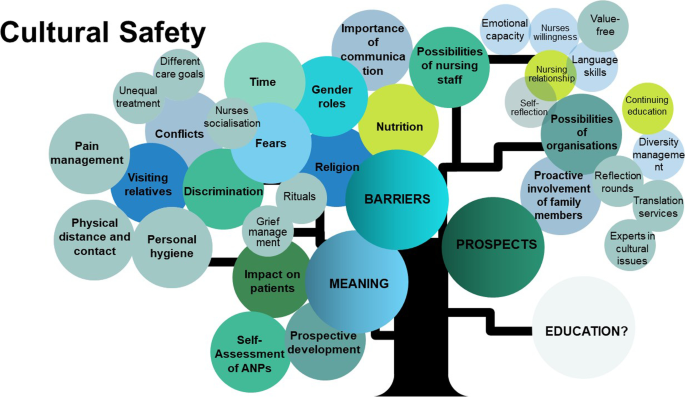

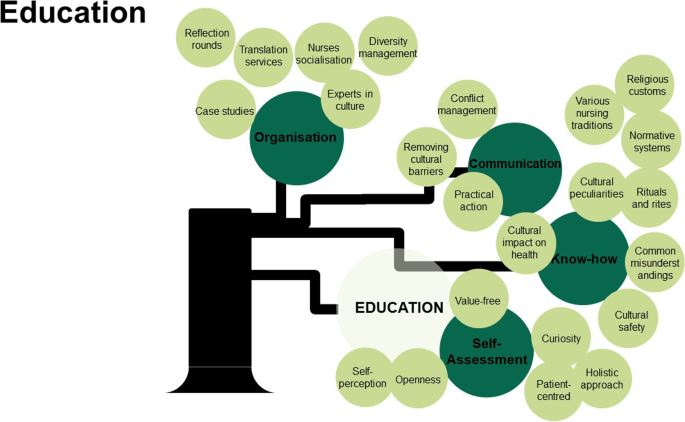

Eliminating indigenous and ethnic health inequities requires addressing the determinants of health inequities which includes institutionalised racism, and ensuring a health care system that delivers appropriate and equitable care. There is growing recognition of the importance of cultural competency and cultural safety at both individual health practitioner and organisational levels to achieve equitable health care. Some jurisdictions have included cultural competency in health professional licensing legislation, health professional accreditation standards, and pre-service and in-service training programmes. However, there are mixed definitions and understandings of cultural competency and cultural safety, and how best to achieve them.

A literature review of 59 international articles on the definitions of cultural competency and cultural safety was undertaken. Findings were contextualised to the cultural competency legislation, statements and initiatives present within Aotearoa New Zealand, a national Symposium on Cultural Competence and Māori Health, convened by the Medical Council of New Zealand and Te Ohu Rata o Aotearoa – Māori Medical Practitioners Association (Te ORA) and consultation with Māori medical practitioners via Te ORA.

Health practitioners, healthcare organisations and health systems need to be engaged in working towards cultural safety and critical consciousness. To do this, they must be prepared to critique the ‘taken for granted’ power structures and be prepared to challenge their own culture and cultural systems rather than prioritise becoming ‘competent’ in the cultures of others. The objective of cultural safety activities also needs to be clearly linked to achieving health equity. Healthcare organisations and authorities need to be held accountable for providing culturally safe care, as defined by patients and their communities, and as measured through progress towards achieving health equity.

Conclusions

A move to cultural safety rather than cultural competency is recommended. We propose a definition for cultural safety that we believe to be more fit for purpose in achieving health equity, and clarify the essential principles and practical steps to operationalise this approach in healthcare organisations and workforce development. The unintended consequences of a narrow or limited understanding of cultural competency are discussed, along with recommendations for how a broader conceptualisation of these terms is important.

Introduction

Internationally, Indigenous and minoritorised ethnic groups experience inequities in their exposure to the determinants of health, access to and through healthcare and receipt of high quality healthcare [ 1 ]. The role of health providers and health systems in creating and maintaining these inequities is increasingly under investigation [ 2 ]. As such, the cultural competency and cultural safety of healthcare providers are now key areas of concern and issues around how to define these terms have become paramount, particularly within a Aotearoa New Zealand (NZ) context [ 3 ]. This article explores international literature to clarify the concepts of cultural competency and cultural safety in order to better inform both local and international contexts.

In NZ, Māori experience significant inequities in health compared to the non-Indigenous population. In 2010–2012, Māori life expectancy at birth was 7.3 years less than non-Māori [ 4 ] and Māori have on average the poorest health status of any ethnic group in NZ [ 5 , 6 ]. Although Māori experience a high level of health care need, Māori receive less access to, and poorer care throughout, the full spectrum of health care services from preventative to tertiary care [ 7 , 8 ]. This is reflected in lower levels of investigations, interventions, and medicines prescriptions when adjusted for need [ 8 , 9 ]. Māori are consistently and significantly less likely to: get understandable answers to important questions asked of health professionals; have health conditions explained in understandable terms; or feel listened to by doctors or nurses [ 10 ]. The disturbing health and social context for Māori and significant inequities across multiple health and social indicators described above provide the ‘needs-based’ rationale for addressing Māori health inequities [ 8 ]. There are equally important ‘rights-based’ imperatives for addressing Indigenous health and health equity [ 11 ], that are reinforced by the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples [ 12 ] and Te Tiriti o Waitangi (Treaty of Waitangi) in NZ.

There are multiple and complex factors that drive Indigenous and ethnic health inequities including a violent colonial history that resulted in decimation of the Māori population and the appropriation of Māori wealth and power, which in turn has led to Māori now having differential exposure to the determinants of health [ 13 ] [ 14 ] and inequities in access to health services and the quality of the care received. Framing ethnic health inequities as being predominantly driven by genetic, cultural or biological differences provides a limited platform for in-depth understanding [ 15 , 16 ]. In addition, whilst socio-economic deprivation is associated with poorer health outcomes, inequities remain even after adjusting for socio-economic deprivation or position [ 17 ]. Health professionals and health care organisations are important contributors to racial and ethnic inequities in health care [ 2 , 13 ]. The therapeutic relationship between a health provider and a patient is especially vulnerable to the influence of intentional or unintentional bias [ 18 , 19 ] leading to the “paradox of well-intentioned physicians providing inequitable care [ 20 ]. Equitable care is further compromised by poor communication, a lack of partnership via participatory or shared decision-making, a lack of respect, familiarity or affiliation and an overall lack of trust [ 18 ]. Healthcare organisations can influence the structure of the healthcare environment to be less likely to facilitate implicit (and explicit) bias for health providers. Importantly, it is not lack of awareness about ‘the culture of other groups’ that is driving health care inequities - inequities are primarily due to unequal power relationships, unfair distribution of the social determinants of health, marginalisation, biases, unexamined privilege, and institutional racism [ 13 ]. Health professional education and health institutions therefore need to address these factors through health professional education and training, organisational policies and practices, as well as broader systemic and structural reform.

Eliminating Indigenous and ethnic health inequities requires addressing the social determinants of health inequities including institutional racism, in addition to ensuring a health care system that delivers appropriate and equitable care. There is growing recognition of the importance of cultural competency and cultural safety at both individual health practitioner and organisational levels to achieve equitable health care delivery. Some jurisdictions have included cultural competency in health professional licensing legislation [ 21 ], health professional accreditation standards, and pre-service and in-service training programmes [ 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 ]. However, there are mixed definitions and understandings of cultural competency and cultural safety, and how best to achieve them. This article reviews how concepts of cultural competency and cultural safety (and related terms such as cultural sensitivity, cultural humility etc) have been interpreted. The unintended consequences of a narrow or limited understanding of cultural competency are discussed, along with recommendations for why broader conceptualisation of these terms is needed to achieve health equity. A move to cultural safety is recommended, with a rationale for why this approach is necessary. We propose a definition for cultural safety and clarify the essential principles of this approach in healthcare organisations and workforce development.

Methods and positioning

This review was originally conducted to inform the Medical Council of New Zealand, in reviewing and updating its approach to cultural competency requirements for medical practitioners in New Zealand Aotearoa. The review and its recommendations are based on the following methods:

An international literature review on cultural competency and cultural safety.

A review of cultural competency legislation, statements and initiatives in NZ, including of the Medical Council of New Zealand (MCNZ).

Inputs from a national Symposium on Cultural Competence and Māori Health, convened for this purpose by the MCNZ and Te Ohu Rata o Aotearoa – Māori Medical Practitioners Association (Te ORA) [ 26 ].

Consultation with Māori medical practitioners (through Te ORA).

The authors reflect expertise that includes Te ORA membership, membership of the Australasian Leaders in Indigenous Medical Education (LIME) (a network to ensure the quality and effectiveness of teaching and learning of Indigenous health in medical education), medical educationalist expertise and Indigenous medical practitioner and public health medicine expertise across Australia and NZ. This experience has been at the forefront of the development of cultural competency and cultural safety approaches within NZ. The analysis has been informed by the framework of van Ryn and colleagues [ 27 ] which frames health provider behaviour within a broader context of societal racism. They note the importance of shifting “ the framing of the problem, from ‘the impact of patient race’ to the more accurate ‘impact of racism’….on clinician cognitions, behaviour, and clinical decision making” [ 27 ].

This review and analysis has been conducted from an Indigenous research positioning that draws from Kaupapa Māori theoretical and research approaches. Therefore, the positioning used to undertake this work aligns to effective Kaupapa Māori research practice that has been described by Curtis (2016) as: transformative; beneficial to Māori; under Māori control; informed by Māori knowledge; aligned with a structural determinants approach to critique issues of power, privilege and racism and promote social justice; non-victim-blaming and rejecting of cultural-deficit theories; emancipatory and supportive of decolonisation; accepting of diverse Māori realities and rejecting of cultural essentialism; an exemplar of excellence; and free to dream [ 28 ].

The literature review searched international journal databases and the grey literature. No year limits were applied to the original searching. Databases searched included: Medline, Psychinfo, Cochrane SR, ERIC, CINAHL, Scopus, Proquest, Google Scholar, EbscoHost and grey literature. Search terms included MeSH terms of cultural competence (key words: cultural safety, cultural awareness, cultural competence, cultural diversity, cultural understanding, knowledge, expertise, skill, responsiveness, respect, transcultural, multicultural, cross-cultur*); education (key words: Educat*, Traini*, Program*, Curricul*, Profession*, Course*, Intervention, Session, Workshop, Skill*, Instruc*, program evaluation); Health Provider (key words: provider, practitioner, health professional, physician, doctor, clinician, primary health care, health personnel, health provider, nurse); Health Services Indigenous (key words: health services Indigenous, ethnic* Minorit*, Indigenous people*, native people). A total of 51 articles were identified via the search above and an additional 8 articles were identified via the authors’ opportunistic searching. A total of 59 articles published between 1989 and 2018 were used to inform this review. Articles reviewed were sourced from the USA, Canada, Australia, NZ, Taiwan and Sweden (Additional file 1 Table S1).

In addition to clarifying concepts of cultural competence and cultural safety, a clearer understanding is required of how best to train and monitor for cultural safety within health workforce contexts. An assessment of the availability and effectiveness of tools and strategies to enhance cultural safety is beyond the scope of this review, but is the subject of a subsequent review in process.

Reviewing cultural competency

Cultural competency is a broad concept that has various definitions drawing from multiple frameworks. Overall, this concept has varying interpretations within and between countries (see Table 1 for specific examples). Introduced in the 1980s, cultural competency has been described as a recognised approach to improving the provision of healthcare to ethnic minority groups with the aim of reducing ethnic health disparities [ 31 ].

One of the earliest [ 49 ] and most commonly cited definitions of cultural competency is sourced from a 1989 report authored by Cross and colleagues in the United States of America [ 29 ] (p.13):

Cultural competence is a set of congruent behaviours, attitudes, and policies that come together in a system, agency, or among professionals and enable that system, agency, or those professionals to work effectively in cross-cultural situations.

Cross et al. [ 29 ] contextualized cultural competency as part of a continuum ranging from the most negative end of cultural destructiveness (e.g. attitudes, policies, and practices that are destructive to cultures and consequently to the individuals within the culture such as cultural genocide) to the most positive end of cultural proficiency (e.g. agencies that hold culture in high esteem, who seek to add to the knowledge base of culturally competent practice by conducting research and developing new therapeutic approaches based on culture). Other points along this continuum include: cultural incapacity , cultural blindness and cultural pre-competence (Table 1 ).

By the time that cultural competency became to be better understood in the late 1990s, there had been substantial growth in the number of definitions, conceptual frameworks and related terms [ 31 , 50 , 51 , 52 ]. Table 1 provides a summary of the multiple, interchangeable, terms such as: cultural awareness ; cultural sensitivity ; cultural humility ; cultural security ; cultural respect ; cultural adaptation ; and transcultural competence or effectiveness . Unfortunately, this rapid growth in terminology and theoretical positioning(s), further confused by variations in policy uptake across the health sector, reduced the potential for a common, shared understanding of what cultural competency represents and therefore what interventions are required. Table 2 outlines the various definitions of cultural competency from the literature.

Cultural competence was often defined within an individually-focused framework, for example, as:

the ability of individuals to establish effective interpersonal and working relationships that supersede cultural differences by recognizing the importance of social and cultural influences on patients, considering how these factors interact, and devising interventions that take these issues into account [ 53 ] (p.2).

Some positionings for cultural competency have been critiqued for promoting the notion that health-care professionals should strive to (or even can) master a certain level of functioning, knowledge and understanding of Indigenous culture [ 61 ]. Cultural competency is limited when it focuses on acquiring knowledge, skills and attitudes as this infers that it is a ‘static’ level of achievement [ 58 ]:

“cultural competency” is frequently approached in ways which limit its goals to knowledge of characteristics, cultural beliefs, and practices of different nonmajority groups, and skills and attitudes of empathy and compassion in interviewing and communicating with nonmajority groups. Achieving cultural competence is thus often viewed as a static outcome: One is “competent” in interacting with patients from diverse backgrounds much in the same way as one is competent in performing a physical exam or reading an EKG. Cultural competency is not an abdominal exam . It is not a static requirement to be checked off some list but is something beyond the somewhat rigid categories of knowledge, skills, and attitudes ( p.783).

By the early 2000s, governmental policies and cultural competency experts [ 50 , 54 ] had begun to articulate cultural competency in terms of both individual and organizational interventions, and describe it with a broader, systems-level focus, e.g.:

the ability of systems to provide care to patients with diverse values, beliefs and behaviours, including tailoring delivery to meet patients’ social, cultural, and linguistic needs [ 54 ] (p. v).

Moreover, some commentators began to articulate the importance of critical reflection to cultural competency. For example, Garneau and Pepin [ 55 ] align themselves more closely to the notion of cultural safety when they describe cultural competency as:

a complex know-act grounded in critical reflection and action, which the health care professional draws upon to provide culturally safe, congruent, and effective care in partnership with individuals, families, and communities living health experiences, and which takes into account the social and political dimensions of care [ 55 ] (p. 12).

Reviewing cultural safety

A key difference between the concepts of cultural competency and cultural safety is the notion of ‘power’. There is a large body of work, developed over many years, describing the nuances of the two terms [ 34 , 36 , 38 , 43 , 46 , 49 , 59 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 , 68 , 69 ]. Similar to cultural competency, this concept has varying interpretations within and between countries. Table 3 summarises the definitions and use of cultural safety from the literature. Cultural safety foregrounds power differentials within society, the requirement for health professionals to reflect on interpersonal power differences (their own and that of the patient), and how the transfer of power within multiple contexts can facilitate appropriate care for Indigenous people and arguably for all patients [ 32 ].

The term cultural safety first was first proposed by Dr. Irihapeti Ramsden and Māori nurses in the 1990s [ 74 ], and in 1992 the Nursing Council of New Zealand made cultural safety a requirement for nursing and midwifery education [ 32 ]. Cultural safety was described as providing:

a focus for the delivery of quality care through changes in thinking about power relationships and patients’ rights [ 32 ] . (p.493).

Cultural safety is about acknowledging the barriers to clinical effectiveness arising from the inherent power imbalance between provider and patient [ 65 ]. This concept rejects the notion that health providers should focus on learning cultural customs of different ethnic groups. Instead, cultural safety seeks to achieve better care through being aware of difference, decolonising, considering power relationships, implementing reflective practice, and by allowing the patient to determine whether a clinical encounter is safe [ 32 , 65 ] .

Cultural safety requires health practitioners to examine themselves and the potential impact of their own culture on clinical interactions. This requires health providers to question their own biases, attitudes, assumptions, stereotypes and prejudices that may be contributing to a lower quality of healthcare for some patients. In contrast to cultural competency, the focus of cultural safety moves to the culture of the clinician or the clinical environment rather than the culture of the ‘exotic other’ patient.

There is debate over whether cultural safety reflects an end point along a continuum of cultural competency development, or, whether cultural safety requires a paradigm shift associated with a transformational jump in cultural awareness. Dr. Irihapeti Ramsden [ 75 ] originally described the process towards achieving cultural safety in nursing and midwifery practice as a step-wise progression from cultural awareness through to cultural sensitivity and on to cultural safety. However, Ramsden was clear that the terms cultural awareness and cultural sensitivity were separate concepts and that they were not interchangeable with cultural safety. Despite some authors interpreting Ramsden’s original description of cultural safety as involving three steps along a continuum [ 35 ] other authors view a move to cultural safety as more of a ‘paradigm shift’ [ 63 ]:

where the movement from cultural competence to cultural safety is not merely another step on a linear continuum, but rather a more dramatic change of approach. This conceptualization of cultural safety represents a more radical, politicized understanding of cultural consideration, effectively rejecting the more limited culturally competent approach for one based not on knowledge but rather on power [ 63 ]. (p.10).

Regardless of whether cultural safety represents movement along a continuum or a paradigm shift, commentators are clear that the concept of cultural safety aligns with critical theory, where health providers are invited to “examine sources of repression, social domination, and structural variables such as class and power” [ 71 ] (p.144) and “social justice, equity and respect” [ 76 ] (p.1). This requires a movement to critical consciousness, involving critical self-reflection: “ a stepping back to understand one’s own assumptions, biases, and values, and a shifting of one’s gaze from self to others and conditions of injustice in the world.” [ 58 ] (p.783).

Why a narrow understanding of cultural competency may be harmful

Unfortunately, regulatory and educational health organisations have tended to frame their understanding of cultural competency towards individualised rather than organisational/systemic processes, and on the acquisition of cultural-knowledge rather than reflective self-assessment of power, priviledge and biases. There are a number of reasons why this approach can be harmful and undermine progress on reducing health inequities.

Individual-level focused positionings for cultural competency perpetuate a process of “othering”, that identifies those that are thought to be different from oneself or the dominant culture. The consequences for persons who experience othering include alienation, marginalization, decreased opportunities, internalized oppression, and exclusion [ 77 ]. To foster safe and effective health care interactions, those in power must actively seek to unmask othering practices [ 78 ].

“Other-focused” approaches to cultural competency promote oversimplified understandings of other cultures based on cultural stereotypes, including a tendency to homogenise Indigenous people into a collective ‘they’ [ 79 ]. This type of cultural essentialism not only leads to health care providers making erroneous assumptions about individual patients which may undermine the provision of good quality care [ 31 , 53 , 58 , 63 , 64 ], but also reinforces a racialised, binary discourse, used to repeatedly dislocate and destabilise Indigenous identity formations [ 80 ]. By ignoring power, narrow approaches to cultural competency perpetuate deficit discourses that place responsibility for problems with the affected individuals or communities [ 81 ], overlooking the role of the health professional, the health care system and broader socio-economic structures. Inequities in access to the social determinants of health have their foundations in colonial histories and subsequent imbalances in power that have consistently benefited some over others. Health equity simply cannot be achieved without acknowledging and addressing differential power, in the healthcare interaction, and in the broader health system and social structures (including in decision making and resource allocation) [ 82 ].

An approach to cultural competency that focuses on acquiring knowledge, skills and attitudes is problematic because it suggests that competency can be fully achieved through this static process [ 58 ]. Cultural competency does not have an endpoint, and a “tick-box” approach may well lull practitioners into a falsely confident space. These dangers underscore the importance of framing cultural safety as an ongoing and reflective process, focused on ‘critical consciousness’. There will still be a need for health professionals to have a degree of knowledge and understanding of other cultures, but this should not be confused with or presented as efforts to address cultural safety. Indeed, as discussed above, this information alone can be dangerous without deep self-reflection about how power and privilege have been redistributed during those processes and the implications for our systems and practice.

By neglecting the organisational/systemic drivers of health care inequities, individual-level focused positionings for cultural competency are fundementally limited in their ability to impact on health inequities. Healthcare organisations influence health provider bias through the structure of the healthcare environment, including factors such as their commitment to workforce training, accountability for equity, workplace stressors, and diversity in workforce and governance [ 27 ]. Working towards cultural safety should not be viewed as an intervention purely at the level of the health professional – although a critically conscious and empathetic health professional is certainly important. The evidence clearly emphasises the important role that healthcare organisations (and society at large) can have in the creation of culturally safe environments [ 31 , 32 , 46 , 60 , 69 ]. Cultural safety initiatives therefore should target both individual health professionals and health professional organisations to intervene positively towards achieving health equity.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the concept of cultural safety is often more confronting and challenging for health institutions, professionals, and students than that of cultural competency. Regardless, it has become increasingly clear that health practitioners, healthcare organisations and health systems all need to be engaged in working towards cultural safety and critical consciousness. To do this, they must be prepared to critique the ‘taken for granted’ power structures and be prepared to challenge their own culture, biases, privilege and power rather than attempt to become ‘competent’ in the cultures of others.

Redefining cultural safety to achieve health equity

It is clear from reviewing the current evidence associated with cultural competency and cultural safety that a shift in approach is required. We recommend an approach to cultural safety that encompasses the following core principles:

Be clearly focused on achieving health equity, with measureable progress towards this endpoint;

Be centred on clarified concepts of cultural safety and critical consciousness rather than narrow based notions of cultural competency;

Be focused on the application of cultural safety within a healthcare systemic/organizational context in addition to the individual health provider-patient interface;

Focus on cultural safety activities that extend beyond acquiring knowledge about ‘other cultures’ and developing appropriate skills and attitudes and move to interventions that acknowledge and address biases and stereotypes;

Promote the framing of cultural safety as requiring a focus on power relationships and inequities within health care interactions that reflect historical and social dynamics.

Not be limited to formal training curricula but be aligned across all training/practice environments, systems, structures, and policies.

We recommend that the following definition for cultural safety is adopted by healthcare organisations:

“Cultural safety requires healthcare professionals and their associated healthcare organisations to examine themselves and the potential impact of their own culture on clinical interactions and healthcare service delivery. This requires individual healthcare professionals and healthcare organisations to acknowledge and address their own biases, attitudes, assumptions, stereotypes, prejudices, structures and characteristics that may affect the quality of care provided. In doing so, cultural safety encompasses a critical consciousness where healthcare professionals and healthcare organisations engage in ongoing self-reflection and self-awareness and hold themselves accountable for providing culturally safe care, as defined by the patient and their communities, and as measured through progress towards acheiveing health equity. Cultural safety requires healthcare professionals and their associated healthcare organisations to influence healthcare to reduce bias and achieve equity within the workforce and working environment”.

In operationalising this approach to cultural safety, organisations (health professional training bodies, healthcare organisations etc) should begin with a self-review of the extent to which they meet expectations of cultural safety at a systemic and organizational level and identify an action plan for development. The following steps should also be considered by healthcare organisations and regulators to take a more comprehensive approach to cultural safety:

Mandate evidence of engagement and transformation in cultural safety activities as a part of vocational training and professional development;

Include evidence of cultural safety (of organisations and practitioners) as a requirement for accreditation and ongoing certification;

Ensure that cultural safety is assessed by the systematic monitoring and assessment of inequities (in health workforce and health outcomes);

Require cultural safety training and performance monitoring for staff, supervisors and assessors;

Acknowledge that cultural safety is an independent requirement that relates to, but is not restricted to, expectations for competency in ethnic or Indigenous health.

Cultural competency, cultural safety and related terms have been variably defined and applied. Unfortunately, regulatory and educational health organisations have tended to frame their understanding of cultural competency towards individualised rather than organisational/systemic processes, and on the acquisition of cultural-knowledge rather than reflective self-assessment of power, priviledge and biases. This positioning has limited the impact on improving health inequities. A shift is required to an approach based on a transformative concept of cultural safety, which involves a critique of power imbalances and critical self-reflection.

We propose principles and a definition for cultural safety that addresses the key factors identified as being responsible for ethnic inequities in health care, and which we therefore believe is fit for purpose in Aotearoa New Zealand and internationally. We hope this will be a useful starting point for users to further reflect on the work required for themselves, and their organisations, to contribute to the creation of culturally safe environments and therefore to the elimination of Indigenous and ethnic health inequities. More work is needed on how best to train and monitor for cultural safety within health workforce contexts.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

Leaders in Indigenous Medical Education network

Medical Council of New Zealand

Aotearoa New Zealand

Te Ohu Rata o Aotearoa – Māori Medical Practitioners Association

Anderson I, et al. Indigenous and tribal peoples’ health (the lancet–Lowitja Institute global collaboration): a population study. Lancet. 2016;388(10040):131–57.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Smedley B, Stith A, Nelson A. Eds. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. 2002. National Academy Press: Washington.

Pigou, P. and N. Joseph, Programme Scope: Cultural competence, partnership and health equity . 2017, New Zealand Medical Council of New Zealand and Te Ohu Rata O Aotearoa: Wellington. p. 1–9.

Statistics New Zealand. Life Expectancy . NZ Social Indicators 2015 [cited 2016 January 7]; Available from: http://www.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/snapshots-of-nz/nz-social-indicators/Home/Health/life-expectancy.aspx .

Jansen P, Jansen D. Māori and health , in Cole's medical practice in New Zealand , I.M. St George, editor. 2013. Medical Council of New Zealand: Wellington.

Ministry of Health, Tatau Kahukura: Māori Health Chart Book . 2006, Ministry of Health: Wellington.

Davis P, et al. Quality of hospital care for Maori patients in New Zealand: retrospective cross-sectional assessment. Lancet. 2006;367(9526):1920–5.

Ministry of Health, Tatau Kahukura: Māori Health Chart Book 2015 (3rd edition) . 2015, Ministry of Health: Wellington.

Metcalfe S, et al. Te Wero tonu-the challenge continues: Māori access to medicines 2006/07-2012/13 update. - PubMed - NCBI. N Z Med J. 2018;131(1485):27–47.

PubMed Google Scholar