VIDEO COURSE

Finish your draft in our 3-month master class. Sign up now to watch a free lesson!

Learn How to Write a Novel

Finish your draft in our 3-month master class. Enroll now for daily lessons, weekly critique, and live events. Your first lesson is free!

Guides • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Nov 22, 2023

Story Structure: 7 Types All Writers Should Know

About the author.

Reedsy's editorial team is a diverse group of industry experts devoted to helping authors write and publish beautiful books.

About Martin Cavannagh

Head of Content at Reedsy, Martin has spent over eight years helping writers turn their ambitions into reality. As a voice in the indie publishing space, he has written for a number of outlets and spoken at conferences, including the 2024 Writers Summit at the London Book Fair.

Nothing makes the challenging task of crafting your first book feel more attainable than adopting a story structure to help you plot your narrative.

While using a pre-existing blueprint might make you worry about ending up with a formulaic, predictable story, you can probably analyze most of your favorite books using various narrative structures that writers have been using for decades (if not centuries)!

This post will reveal seven distinct story structures that any writer can use to build a compelling narrative. But first…

What is story structure?

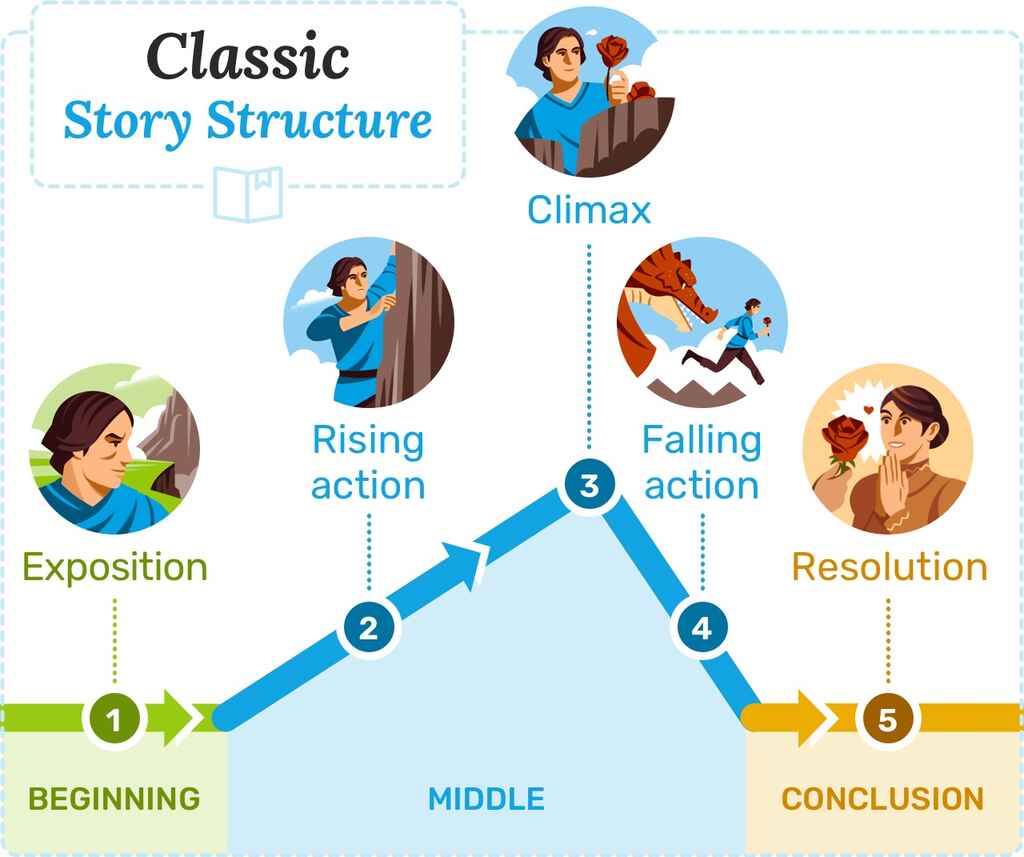

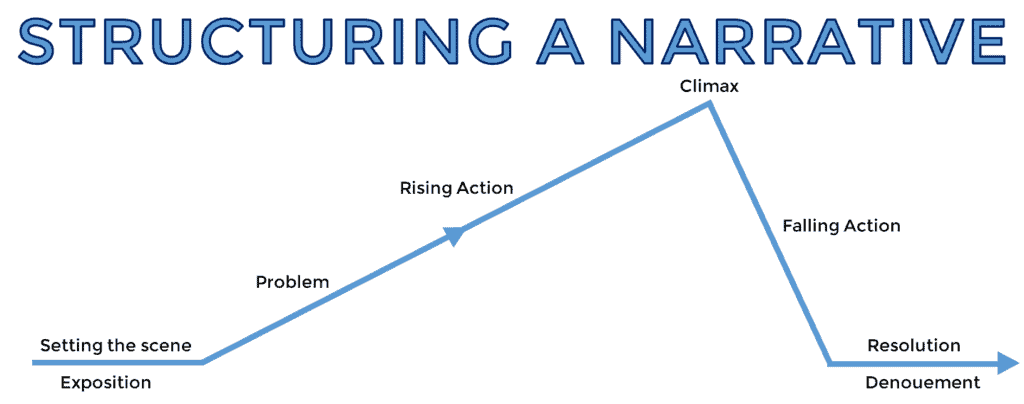

Story structure is the order in which plot events are told to the reader or audience . While stories can be told in a wide variety of ways, most Western story structures commonly share certain elements: exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution.

A tightly controlled structure will answer a reader's questions, provide a climax followed by resolution and information at the end of the story, further the characters’ development, and unravel any central conflicts. In other words, it's responsible for a satisfying narrative experience that accomplishes the author’s aims.

Writing is an art, but if there’s one part of the craft that’s closer to science, this would be it. Become a master of story structure, and you will have the world at your feet.

Classic story structure

When people discuss different story structures, they often talk about the different frameworks used to analyze stories. When you boil them all down, all stories have certain shared elements.

Elements of classic story structure:

- Exposition. This first part establishes a protagonist's normal life and greater desires, and usually culminates in the inciting incident.

- Rising action. The protagonist pursues their new goal and is tested along the way.

- Climax. Our hero achieves their goal — or so they think!

- Falling action. The hero now must deal with the consequences of achieving their goal.

- Resolution. The conclusion tying together the plot, character arcs, and themes.

These are all common ‘ beats ’ to most stories. It can be easier to see these moments in genres with higher stakes (such as a military thriller), but you’ll find them in almost any type of story.

GET ACCOUNTABILITY

Meet writing coaches on Reedsy

Industry insiders can help you hone your craft, finish your draft, and get published.

Seven Story Structures Every Writer Should Know

Now that we’ve established the most essential components of story, let’s look at seven of the most popular story structures used by writers — and how they deploy these components:

- Freytag's Pyramid

- The Hero's Journey

- Three Act Structure

- Dan Harmon's Story Circle

- Fichtean Curve

- Save the Cat Beat Sheet

- Seven-Point Story Structure

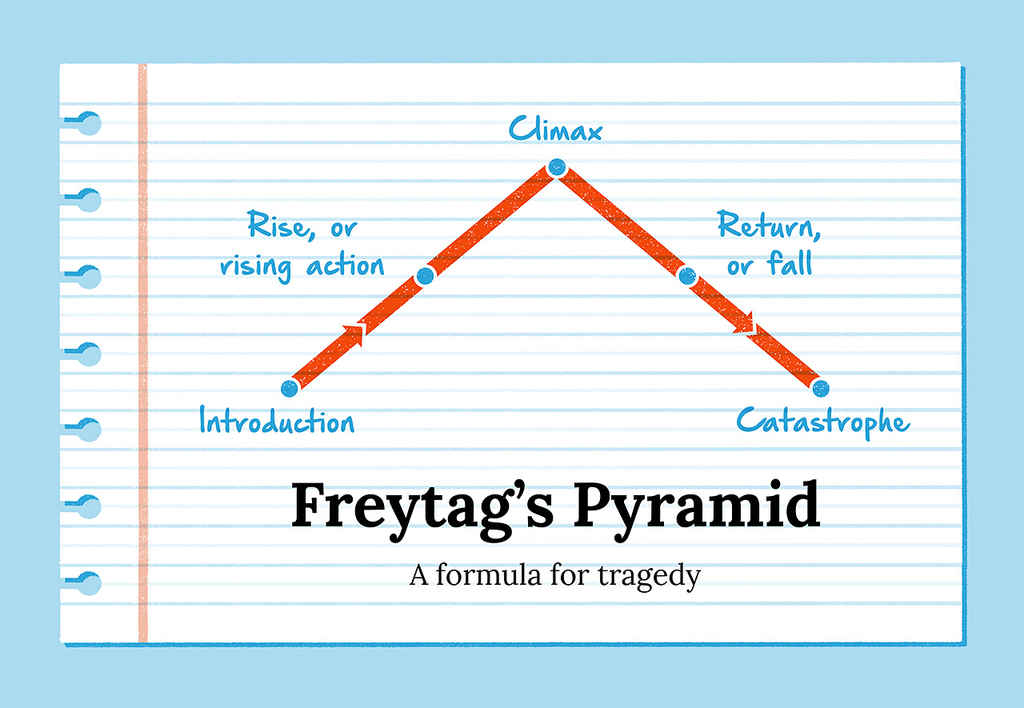

1. Freytag’s Pyramid

- Introduction. The status quo is established; an inciting incident occurs.

- Rise, or rising action. The protagonist actively pursues their goal. The stakes heighten.

- Climax. A point of no return, from which the protagonist can no longer go back to the status quo.

- Return, or fall. In the aftermath of the climax, tension builds, and the story heads inevitably towards...

- Catastrophe. The protagonist is brought to their lowest point. Their greatest fears have come true.

This structural model is less frequently used in modern storytelling, partly due to readers’ limited appetite for tragic narratives (although you can still spot a few tragic heroes in popular literature today). By and large, commercial fiction, films, and television will see a protagonist overcome their obstacles to find some small measure of success. That said, it’s still useful to understand the Pyramid as a foundational structure in Western literature — and you will still see it occasionally in the most depressing contemporary tales.

To learn more, read our full guide on Freytag’s Pyramid here .

If you struggle to structure a novel, sign up for our How to Write a Novel course to finish a novel in just 3 months.

NEW REEDSY COURSE

How to Write a Novel

Enroll in our course and become an author in three months.

2. The Hero’s Journey

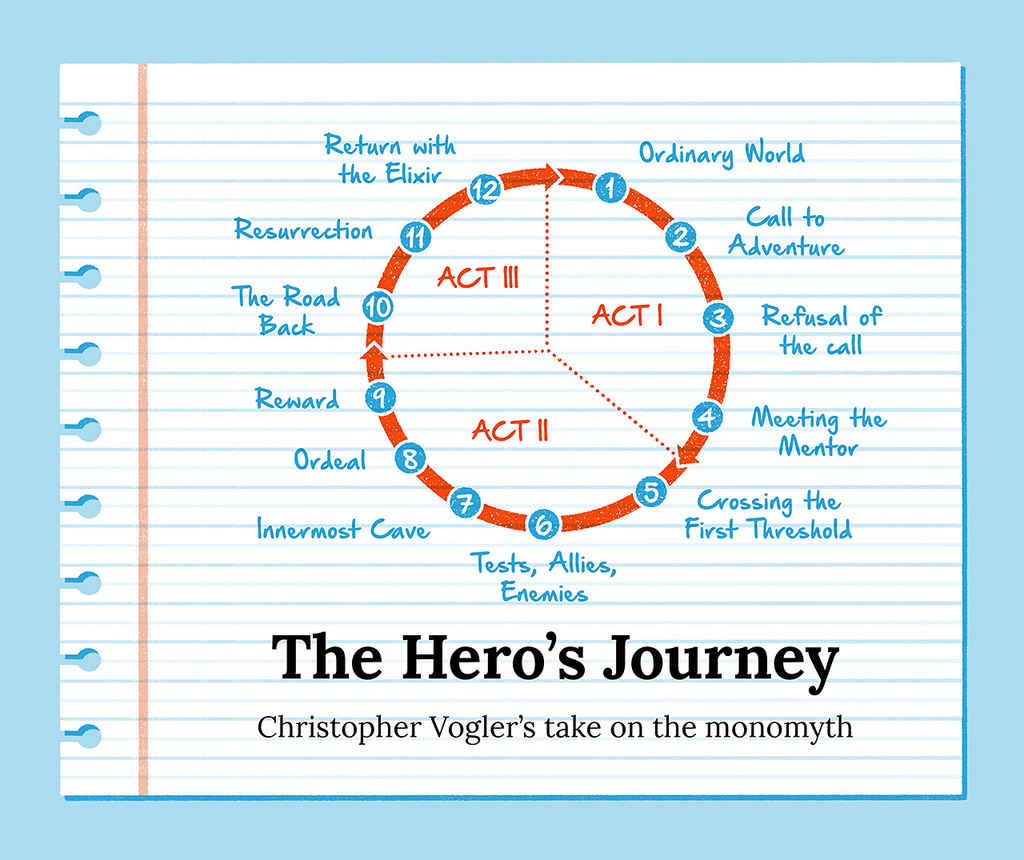

Campbell’s original structure uses terminology that lends itself well to epic tales of bravery and triumph — with plot points like “Belly of the Whale,” “Woman as the Temptress,” and “The Magic Flight.” To make The Hero’s Journey more accessible, Disney executive Christopher Vogler created a simplified version that has become popular amongst mainstream storytellers.

Here, we’ll look at Vogler’s streamlined, 12-step version of The Hero’s Journey.

- The Ordinary World. The hero’s everyday life is established.

- The Call of Adventure. Otherwise known as the inciting incident.

- Refusal of the Call. For a moment, the hero is reluctant to take on the challenge.

- Meeting the Mentor. Our hero meets someone who prepares them for what lies ahead — perhaps a parental figure, a teacher, a wizard, or a wise hermit.

- Crossing the First Threshold. The hero steps out of their comfort zone and enters a ‘new world.’

- Tests, Allies, Enemies. Our protagonist faces new challenges — and maybe picks up some new friends. Think of Dorothy on the Yellow Brick Road.

- Approach to the Inmost Cave. The hero gets close to their goal. Luke Skywalker reaches the Death Star.

- The Ordeal. The hero meets (and overcomes) their greatest challenge yet.

- Reward (Seizing the Sword). The hero obtains something important they were after, and victory is in sight.

- The Road Back. The hero realizes that achieving their goal is not the final hurdle. In fact, ‘seizing the sword’ may have made things worse for them.

- Resurrection. The hero faces their final challenge — a climactic test that hinges on everything they’ve learned over their journey.

- Return with the Elixir. Having triumphed, our protagonist returns to their old life. Dorothy returns to Kansas; Iron Man holds a press conference to blow his own trumpet .

While Vogler’s simplified steps still retain some of Campbell’s mythological language with its references to swords and elixirs, the framework can be applied to almost any genre of fiction. To see how a ‘realistic’ story can adhere to this structure, check out our guide to the hero’s journey in which we analyze Rocky through this very lens.

FREE OUTLINING APP

Reedsy Studio

Use the Boards feature to plan, organize, or research anything.

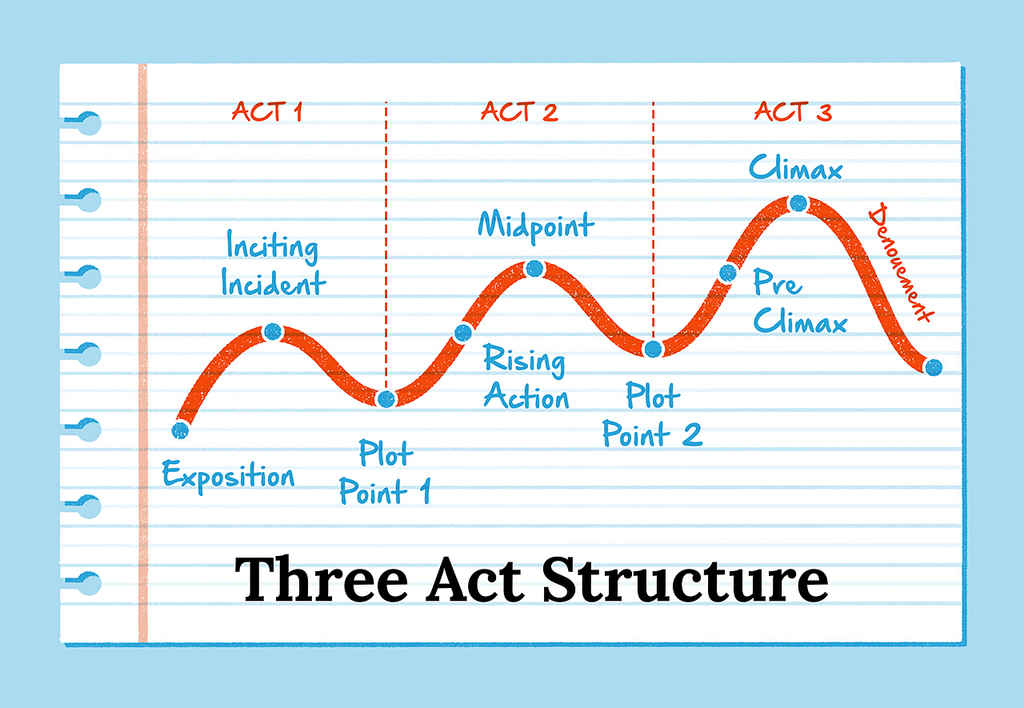

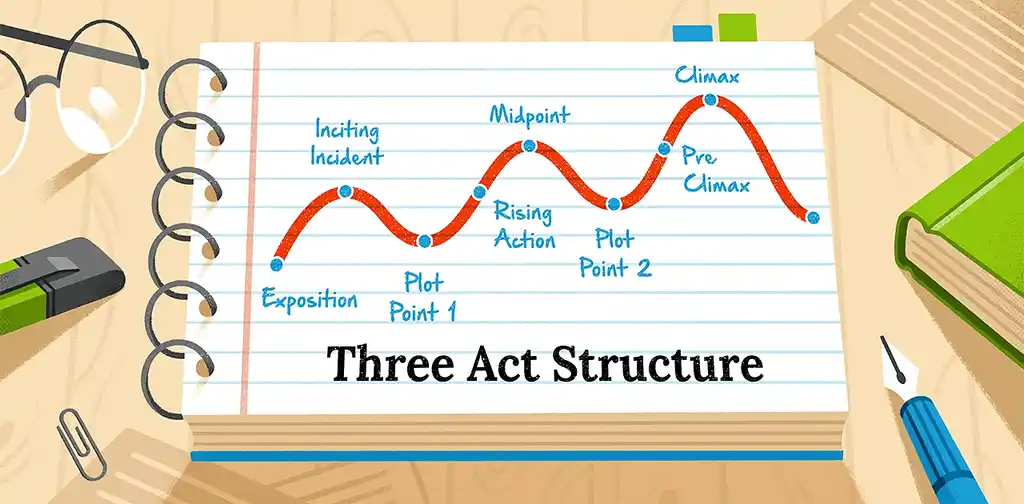

3. Three Act Structure

Act 1: Setup

- Exposition . The status quo or ‘ordinary world’ is established.

- Inciting Incident. An event that sets the story in motion.

- Plot Point One. The protagonist decides to tackle the challenge head-on. She ‘crosses the threshold,’ and the story is now truly moving.

Act 2: Confrontation

- Rising Action. The story's true stakes become clear; our hero grows familiar with her ‘new world’ and has her first encounters with some enemies and allies. (see Tests, Allies, Enemies)

- Midpoint. An event that upends the protagonist’s mission. (Similar to the climax in Freytag’s pyramid)

- Plot Point Two. In the wake of the disorienting midpoint, the protagonist is tested — and fails. Her ability to succeed is now in doubt.

Act 3: Resolution

- Pre Climax. The night is darkest before dawn. The protagonist must pull herself together and choose between decisive action and failure.

- Climax. She faces off against her antagonist one last time. Will she prevail?

- Denouement. All loose ends are tied up. The reader discovers the consequences of the climax. A new status quo is established.

When we speak about a confrontation with an antagonist, this doesn’t always mean a fight to the death. In some cases, the antagonist might be a love rival, a business competitor, or merely an internal or environmental conflict that our protagonist has been struggling with the entire story.

If you’re interested in using this model to plot your own story, read our guide to the three-act structure , and be sure to sign up to our free course on the subject.

FREE COURSE

How to Plot a Novel in Three Acts

In 10 days, learn how to plot a novel that keeps readers hooked

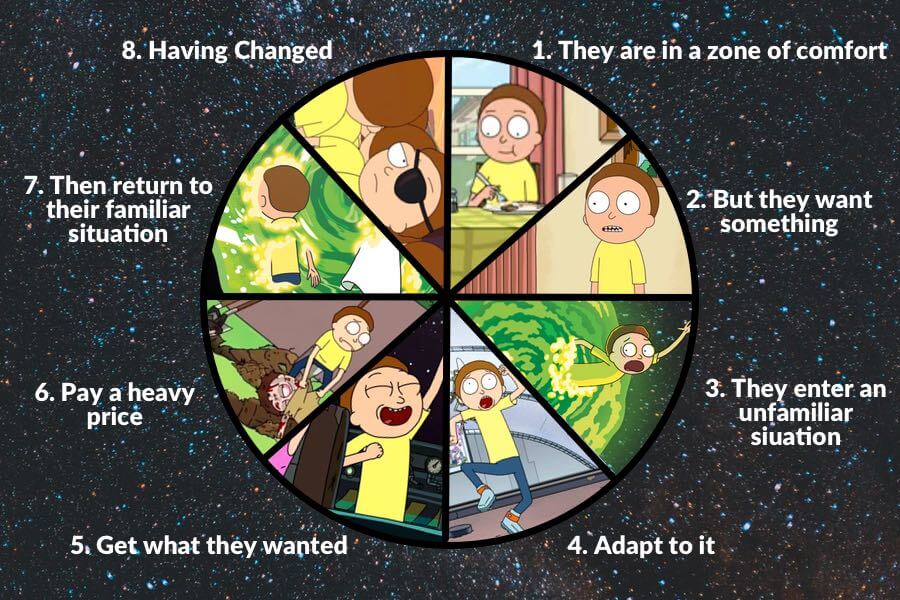

4. Dan Harmon's Story Circle

Another variation on Campbell’s monomyth structure, the Story Circle is an approach developed by Rick and Morty co-creator Dan Harmon. Again, heavily inspired by the Hero's Journey, the benefit of Harmon's approach is its focus on the protagonist's character arc. Instead of referring to abstract concepts like 'story midpoint' and 'denouement', each beat in the story circle forces the writer to think about the character's wants and needs.

- A character is in a zone of comfort... This is the establishment of the status quo.

- But they want something... This 'want' could be something long-standing and brought to the fore by an inciting incident.

- They enter an unfamiliar situation... The protagonist must do something new in their pursuit of the thing they want.

- Adapt to it... Faced with some challenges, they struggle then begin to succeed.

- Get what they wanted... Usually a false victory.

- Pay a heavy price for it... They realize that what they 'wanted' wasn't what they 'needed'.

- Then return to their familiar situation... armed with a new truth.

- Having changed... For better or worse.

Created by a writer whose chosen medium is the 30-minute sitcom, this structure is worded in a way that sidesteps the need for a protagonist to undergo life-changing transformations with each story. After all, for a comedy to continue for six seasons (and a movie) its characters can't completely transform at the end of each episode. They can, however, learn small truths about themselves and the world around them — which, like all humans, they can quickly forget about if next week's episode calls for it.

To learn more and see this structure applied to an episode of Rick and Morty, check out our full post on Dan Harmon's Story Circle .

Side note: for this kind of character-driven plot (and, indeed, for all of these structures), you're going to want to know you're protagonist inside and out. Why not check out some of our character development exercises for help fleshing your characters out, like the profile template below.

FREE RESOURCE

Reedsy’s Character Profile Template

A story is only as strong as its characters. Fill this out to develop yours.

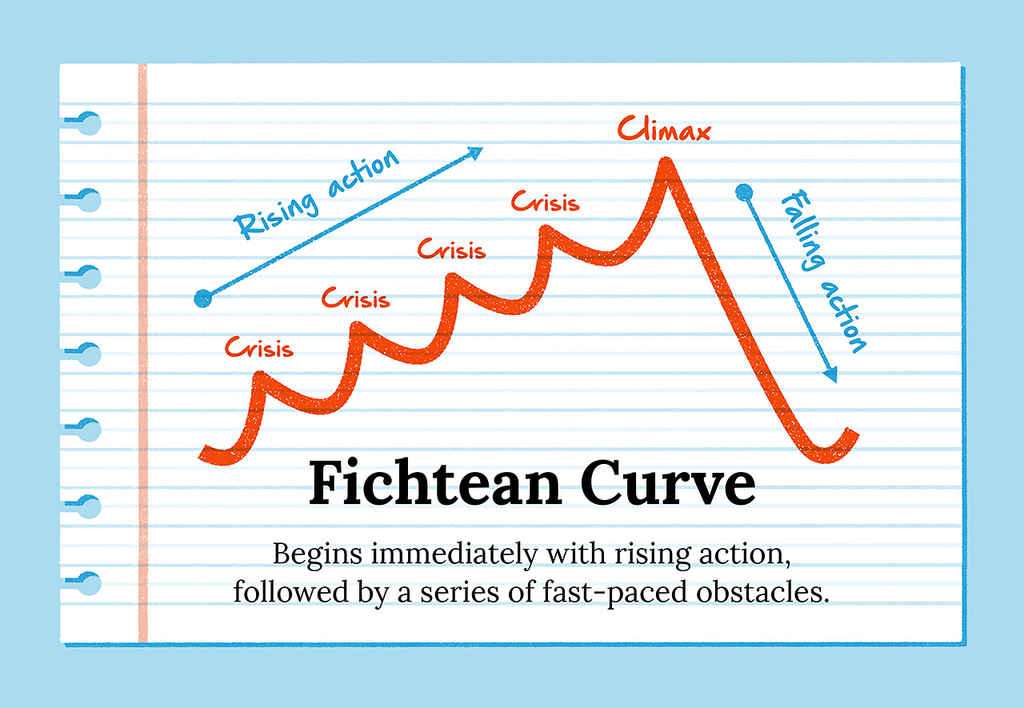

5. Fichtean Curve

Fleshed out in John Gardner’s The Art of Fiction , the Fichtean Curve is a narrative structure that puts our main characters through a series of many obstacles on their way to achieving their overarching goals. Resembling Freytag’s Pyramid, it encourages authors to write narratives packed with tension and mini-crises that keep readers eager to reach the climax.

Bypassing the “ordinary world” setup of many other structures, the Fichtean Curve starts with the inciting incident and goes straight into the rising action. Multiple crises occur, each of which contributes to the readers’ overall understanding of the narrative — replacing the need for the initial exposition.

To discuss this unusual structure, it’s perhaps best to see it in use. We’ll use Celeste Ng’s Everything I Never Told You as an example. Needless to say, spoilers ahead.

Rising Action

- First crisis. Lydia’s family is informed her body was found in a nearby lake. From this first crisis's climax, the narrative flashes back to provide exposition and details of the family’s history.

- Second crisis. In flashbacks, we discover that, 11 years prior, Marilyn abandoned her family to resume her undergraduate studies. In her absence, the family begins to fall apart. Marilyn learns she is pregnant and is forced to return home. Having lost her opportunity for further education, she places the pressure of academic success on her children.

- Third crisis. Back in the present, Lydia’s father, James, is cheating on Marilyn. The police decide to close the investigation, ruling Lydia’s death a suicide. This results in a massive argument between her parents, and James leaves to stay with the “other woman.”

- Fourth crisis. Flashback to the day Lydia died. From her perspective, we see that she’s misunderstood by her parents. She mourns her brother’s impending departure for college, leaving her as the sole focus of her parents’ pressure. Isolated, she tries to seduce a friend — who rejects her advances and explains he’s in love with her brother.

- Lydia takes a boat into the lake in the middle of the night — determined to overcome her fear of water and reclaim control of her life. Lydia jumps off the boat, into the water, and out of this life. As in a classical tragedy, this moment is both devastating and inevitable.

Falling Action

- Some level of resolution is achieved, and readers get to at least glimpse the “new norm” for the characters. Lydia’s family lean on one another in their grief. While they may never be able to make their amends with Lydia, they can learn from her death. Not all of the loose ends are tied off, but readers infer the family is on the long road to recovery.

Note: In the rising action stage, all of the crises should build tension towards — and correspond with — the story’s major climax. Like the three-act narrative structure, the Fichtean Curve’s climax typically occurs two-thirds through the book.

While this structure lends itself well to flashback-heavy novels such as Everything I Never Told You, it is also incredibly common in theatre. In stage plays like The Cherry Orchard and A Doll’s House , the action takes place in a fixed time and place, but backstory and character development are revealed through moments of high drama that occur before the audience’s eyes.

For a deeper look at this structure, head to our full post on the Fichtean Curve .

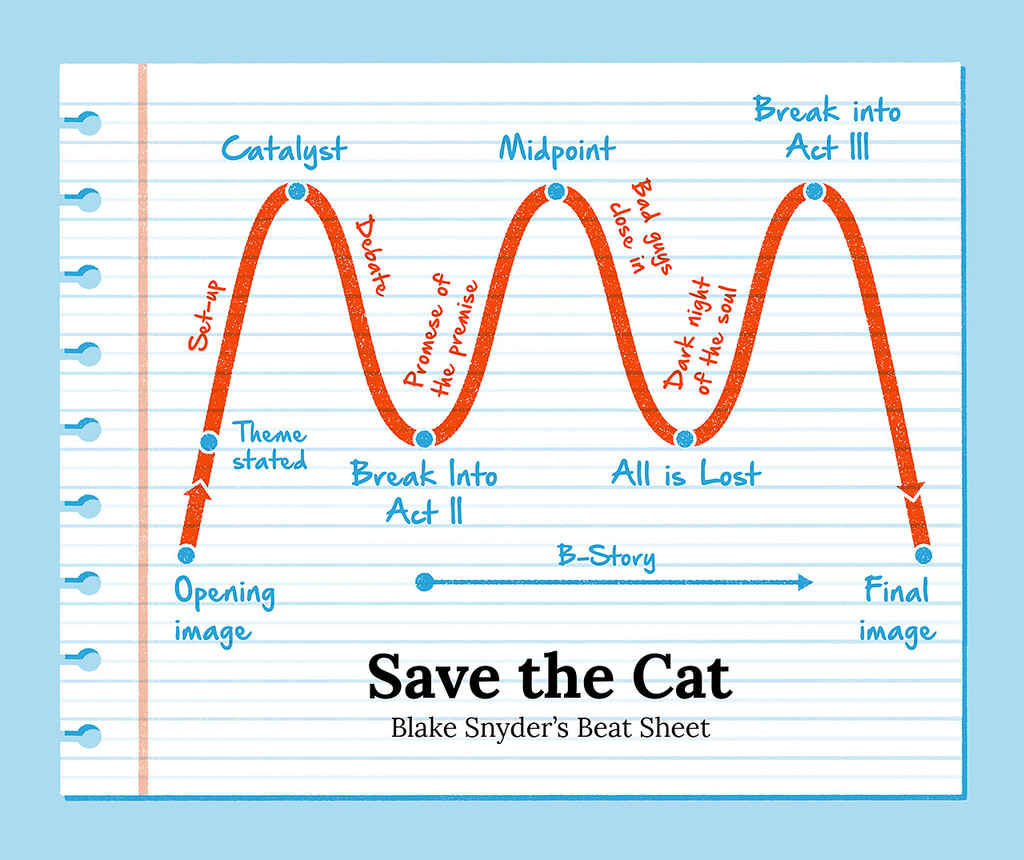

6. Save the Cat Beat Sheet

Another variation of the three-act structure, this framework created by Hollywood screenwriter Blake Snyder, has been widely championed by storytellers across many media forms.

Fun fact: Save the Cat is named for a moment in the set up of a story (usually a film) where our hero does something to endear himself to the audience.

While many structures are reluctant to prescribe exactly when in a story the various beats should take place, Snyder and Save the Cat have no such qualms. The number in the square brackets below refers to the page that the beat should take place — assuming you’re writing a 110-page screenplay.

- Opening Image [1]. The first shot of the film. If you’re starting a novel , this would be an opening paragraph or scene that sucks readers into the world of your story.

- Set-up [1-10]. Establishing the ‘ordinary world’ of your protagonist. What does he want? What is he missing out on?

- Theme Stated [5]. During the setup, hint at what your story is really about — the truth that your protagonist will discover by the end.

- Catalyst [12]. The inciting incident!

- Debate [12-25]. The hero refuses the call to adventure. He tries to avoid the conflict before they are forced into action.

- Break into Two [25]. The protagonist makes an active choice and the journey begins in earnest.

- B Story [30]. A subplot kicks in. Often romantic in nature, the protagonist’s subplot should serve to highlight the theme.

- The Promise of the Premise [30-55]. Often called the ‘fun and games’ stage, this is usually a highly entertaining section where the writer delivers the goods. If you promised an exciting detective story, we’d see the detective in action. If you promised a goofy story of people falling in love, let’s go on some charmingly awkward dates.

- Midpoint [55]. A plot twist occurs that ups the stakes and makes the hero’s goal harder to achieve — or makes them focus on a new, more important goal.

- Bad Guys Close In [55-75]. The tension ratchets up. The hero’s obstacles become greater, his plan falls apart, and he is on the back foot.

- All is Lost [75]. The hero hits rock bottom. He loses everything he’s gained so far, and things are looking bleak. The hero is overpowered by the villain; a mentor dies; our lovebirds have an argument and break up.

- Dark Night of the Soul [75-85-ish]. Having just lost everything, the hero shambles around the city in a minor-key musical montage before discovering some “new information” that reveals exactly what he needs to do if he wants to take another crack at success. (This new information is often delivered through the B-Story)

- Break into Three [85]. Armed with this new information, our protagonist decides to try once more!

- Finale [85-110]. The hero confronts the antagonist or whatever the source of the primary conflict is. The truth that eluded him at the start of the story (established in step three and accentuated by the B Story) is now clear, allowing him to resolve their story.

- Final Image [110]. A final moment or scene that crystallizes how the character has changed. It’s a reflection, in some way, of the opening image.

Some writers may find this structure too prescriptive, but it’s incredible to see how many mainstream stories seem to adhere to it — either by design or coincidence. Over on the Save the Cat website, there are countless examples of films and novels analyzed with Snyder’s 15 beats . You’ll be surprised how accurate some of the timings are for each of the beats.

For a deeper dive into this framework, and to watch this video where Reedsy’s Shaelin plots out a Middle-Grade fantasy novel using Snyder’s method — head to our full post on the Save the Cat Beat Sheet .

7. Seven-Point Story Structure

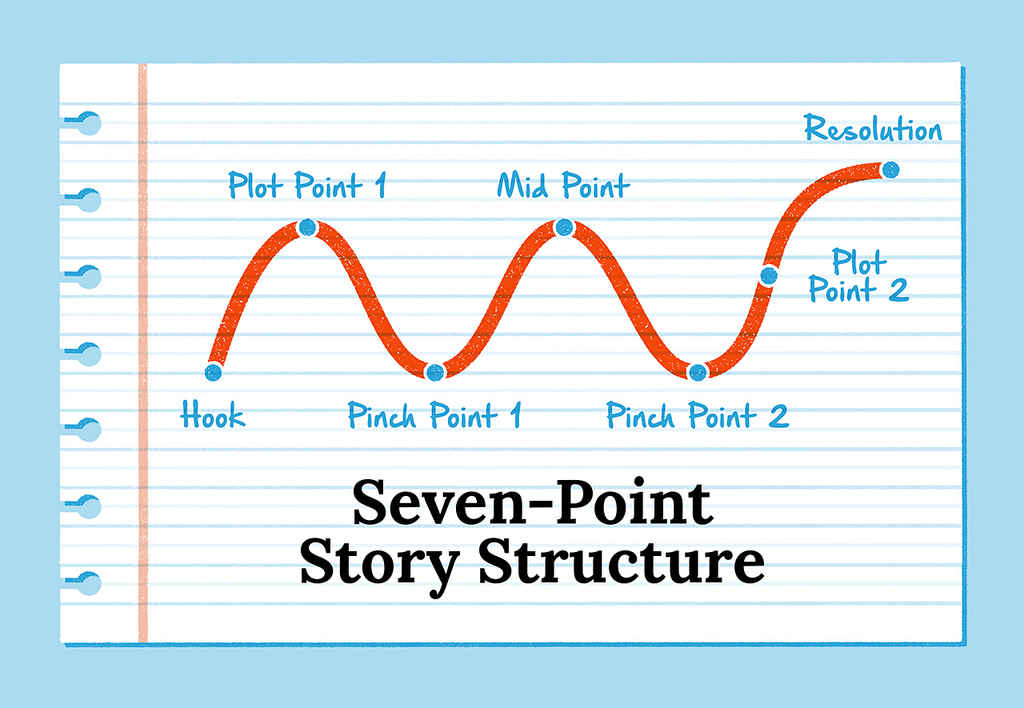

A slightly less detailed adaptation of The Hero’s Journey, the Seven-Point Story Structure focuses specifically on the highs and lows of a narrative arc .

According to author Dan Wells, who developed the Seven-Point Story Structure , writers are encouraged to start at the end, with the resolution, and work their way back to the starting point: the hook. With the ending in mind, they can have their protagonist and plot begin in a state that best contrasts the finale — since this structure is all about dramatic changes from beginning to end.

- The Hook. Draw readers in by explaining the protagonist’s current situation. Their state of being at the beginning of the novel should be in direct contrast to what it will be at the end of the novel.

- Plot Point 1. Whether it’s a person, an idea, an inciting incident, or something else — there should be a "Call to Adventure" of sorts that sets the narrative and character development in motion.

- Pinch Point 1. Things can’t be all sunshine and roses for your protagonist. Something should go wrong here that applies pressure to the main character, forcing them to step up and solve the problem.

- Midpoint. A “Turning Point” wherein the main character changes from a passive force to an active force in the story. Whatever the narrative’s main conflict is, the protagonist decides to start meeting it head-on.

- Pinch Point 2. The second pinch point involves another blow to the protagonist — things go even more awry than they did during the first pinch point. This might involve the passing of a mentor, the failure of a plan, the reveal of a traitor, etc.

- Plot Point 2. After the calamity of Pinch Point 2, the protagonist learns that they’ve actually had the key to solving the conflict the whole time.

- Resolution. The story’s primary conflict is resolved — and the character goes through the final bit of development necessary to transform them from who they were at the start of the novel.

For a deeper look into Wells's approach — including the key to using it — check out our full post on the seven-point story structure .

We've said it before, and we'll say it again: story structures aren't an exact science, and you should feel welcome to stray from the path they present. They're simply there to help you find your narrative's footing — a blueprint for the world you're about to start building.

Join a community of over 1 million authors

Reedsy is more than just a blog. Become a member today to discover how we can help you publish a beautiful book.

Bring your stories to life

Our free writing app lets you set writing goals and track your progress, so you can finally write that book!

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Enter your email or get started with a social account:

Narrative Writing: A Complete Guide for Teachers and Students

MASTERING THE CRAFT OF NARRATIVE WRITING

Narratives build on and encourage the development of the fundamentals of writing. They also require developing an additional skill set: the ability to tell a good yarn, and storytelling is as old as humanity.

We see and hear stories everywhere and daily, from having good gossip on the doorstep with a neighbor in the morning to the dramas that fill our screens in the evening.

Good narrative writing skills are hard-won by students even though it is an area of writing that most enjoy due to the creativity and freedom it offers.

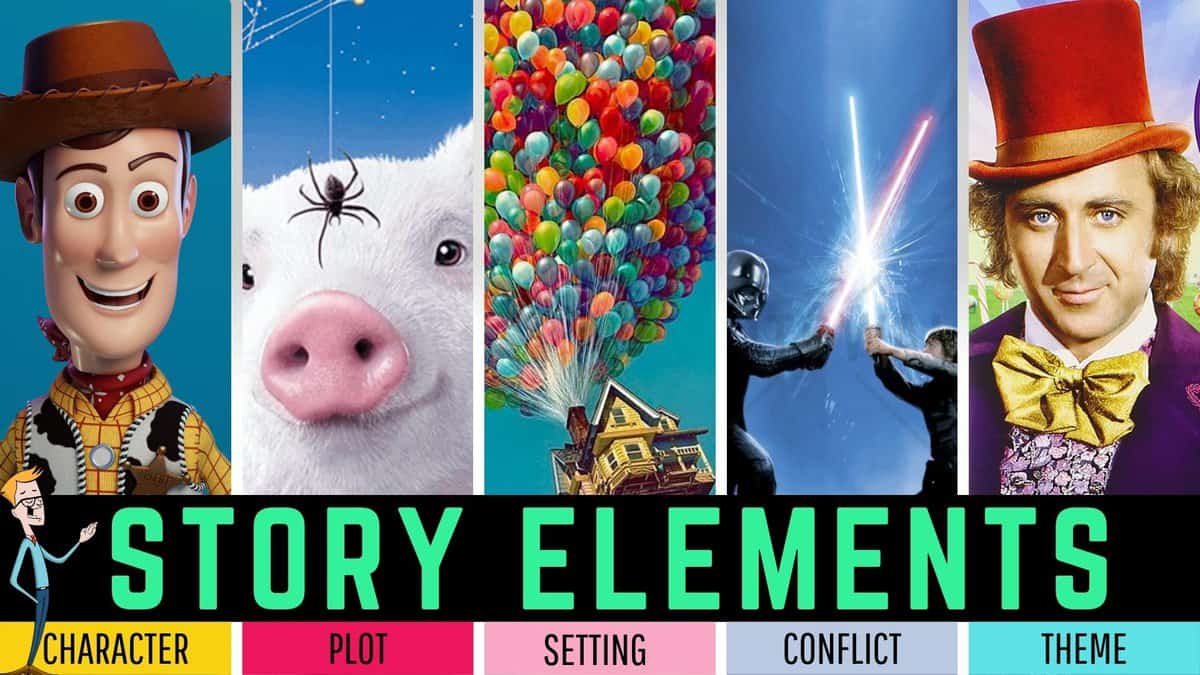

Here we will explore some of the main elements of a good story: plot, setting, characters, conflict, climax, and resolution . And we will look too at how best we can help our students understand these elements, both in isolation and how they mesh together as a whole.

WHAT IS A NARRATIVE?

A narrative is a story that shares a sequence of events , characters, and themes. It expresses experiences, ideas, and perspectives that should aspire to engage and inspire an audience.

A narrative can spark emotion, encourage reflection, and convey meaning when done well.

Narratives are a popular genre for students and teachers as they allow the writer to share their imagination, creativity, skill, and understanding of nearly all elements of writing. We occasionally refer to a narrative as ‘creative writing’ or story writing.

The purpose of a narrative is simple, to tell the audience a story. It can be written to motivate, educate, or entertain and can be fact or fiction.

A COMPLETE UNIT ON TEACHING NARRATIVE WRITING

Teach your students to become skilled story writers with this HUGE NARRATIVE & CREATIVE STORY WRITING UNIT . Offering a COMPLETE SOLUTION to teaching students how to craft CREATIVE CHARACTERS, SUPERB SETTINGS, and PERFECT PLOTS .

Over 192 PAGES of materials, including:

TYPES OF NARRATIVE WRITING

There are many narrative writing genres and sub-genres such as these.

We have a complete guide to writing a personal narrative that differs from the traditional story-based narrative covered in this guide. It includes personal narrative writing prompts, resources, and examples and can be found here.

As we can see, narratives are an open-ended form of writing that allows you to showcase creativity in many directions. However, all narratives share a common set of features and structure known as “Story Elements”, which are briefly covered in this guide.

Don’t overlook the importance of understanding story elements and the value this adds to you as a writer who can dissect and create grand narratives. We also have an in-depth guide to understanding story elements here .

CHARACTERISTICS OF NARRATIVE WRITING

Narrative structure.

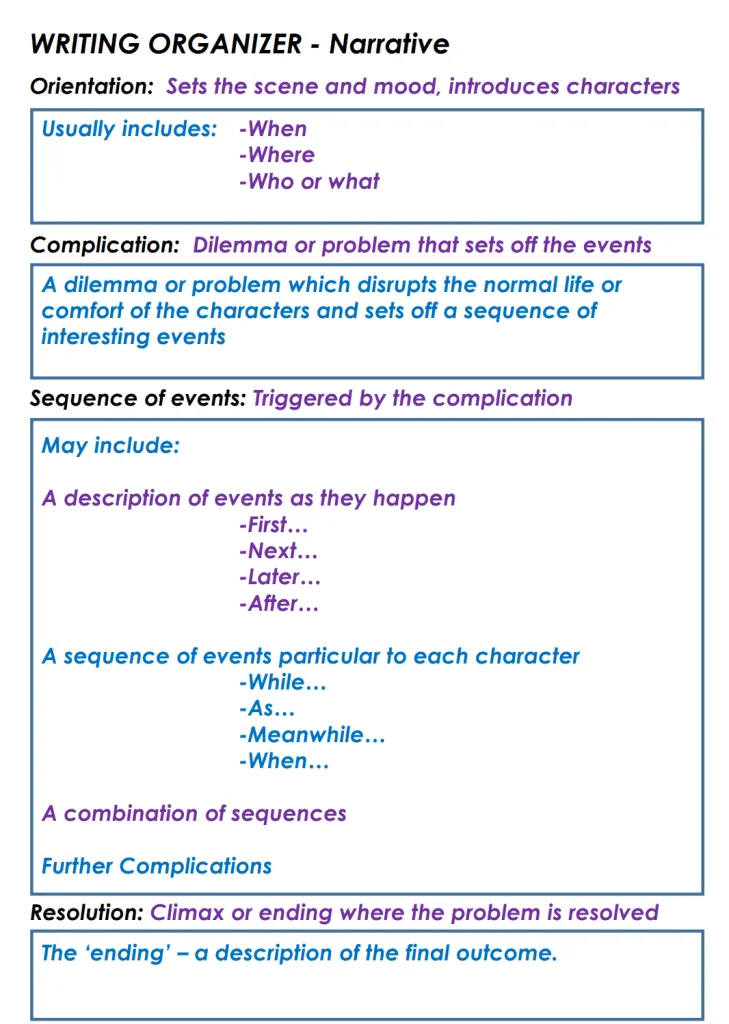

ORIENTATION (BEGINNING) Set the scene by introducing your characters, setting and time of the story. Establish your who, when and where in this part of your narrative

COMPLICATION AND EVENTS (MIDDLE) In this section activities and events involving your main characters are expanded upon. These events are written in a cohesive and fluent sequence.

RESOLUTION (ENDING) Your complication is resolved in this section. It does not have to be a happy outcome, however.

EXTRAS: Whilst orientation, complication and resolution are the agreed norms for a narrative, there are numerous examples of popular texts that did not explicitly follow this path exactly.

NARRATIVE FEATURES

LANGUAGE: Use descriptive and figurative language to paint images inside your audience’s minds as they read.

PERSPECTIVE Narratives can be written from any perspective but are most commonly written in first or third person.

DIALOGUE Narratives frequently switch from narrator to first-person dialogue. Always use speech marks when writing dialogue.

TENSE If you change tense, make it perfectly clear to your audience what is happening. Flashbacks might work well in your mind but make sure they translate to your audience.

THE PLOT MAP

This graphic is known as a plot map, and nearly all narratives fit this structure in one way or another, whether romance novels, science fiction or otherwise.

It is a simple tool that helps you understand and organise a story’s events. Think of it as a roadmap that outlines the journey of your characters and the events that unfold. It outlines the different stops along the way, such as the introduction, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution, that help you to see how the story builds and develops.

Using a plot map, you can see how each event fits into the larger picture and how the different parts of the story work together to create meaning. It’s a great way to visualize and analyze a story.

Be sure to refer to a plot map when planning a story, as it has all the essential elements of a great story.

THE 5 KEY STORY ELEMENTS OF A GREAT NARRATIVE (6-MINUTE TUTORIAL VIDEO)

This video we created provides an excellent overview of these elements and demonstrates them in action in stories we all know and love.

HOW TO WRITE A NARRATIVE

Now that we understand the story elements and how they come together to form stories, it’s time to start planning and writing your narrative.

In many cases, the template and guide below will provide enough details on how to craft a great story. However, if you still need assistance with the fundamentals of writing, such as sentence structure, paragraphs and using correct grammar, we have some excellent guides on those here.

USE YOUR WRITING TIME EFFECTIVELY: Maximize your narrative writing sessions by spending approximately 20 per cent of your time planning and preparing. This ensures greater productivity during your writing time and keeps you focused and on task.

Use tools such as graphic organizers to logically sequence your narrative if you are not a confident story writer. If you are working with reluctant writers, try using narrative writing prompts to get their creative juices flowing.

Spend most of your writing hour on the task at hand, don’t get too side-tracked editing during this time and leave some time for editing. When editing a narrative, examine it for these three elements.

- Spelling and grammar ( Is it readable?)

- Story structure and continuity ( Does it make sense, and does it flow? )

- Character and plot analysis. (Are your characters engaging? Does your problem/resolution work? )

1. SETTING THE SCENE: THE WHERE AND THE WHEN

The story’s setting often answers two of the central questions in the story, namely, the where and the when. The answers to these two crucial questions will often be informed by the type of story the student is writing.

The story’s setting can be chosen to quickly orient the reader to the type of story they are reading. For example, a fictional narrative writing piece such as a horror story will often begin with a description of a haunted house on a hill or an abandoned asylum in the middle of the woods. If we start our story on a rocket ship hurtling through the cosmos on its space voyage to the Alpha Centauri star system, we can be reasonably sure that the story we are embarking on is a work of science fiction.

Such conventions are well-worn clichés true, but they can be helpful starting points for our novice novelists to make a start.

Having students choose an appropriate setting for the type of story they wish to write is an excellent exercise for our younger students. It leads naturally onto the next stage of story writing, which is creating suitable characters to populate this fictional world they have created. However, older or more advanced students may wish to play with the expectations of appropriate settings for their story. They may wish to do this for comic effect or in the interest of creating a more original story. For example, opening a story with a children’s birthday party does not usually set up the expectation of a horror story. Indeed, it may even lure the reader into a happy reverie as they remember their own happy birthday parties. This leaves them more vulnerable to the surprise element of the shocking action that lies ahead.

Once the students have chosen a setting for their story, they need to start writing. Little can be more terrifying to English students than the blank page and its bare whiteness stretching before them on the table like a merciless desert they must cross. Give them the kick-start they need by offering support through word banks or writing prompts. If the class is all writing a story based on the same theme, you may wish to compile a common word bank on the whiteboard as a prewriting activity. Write the central theme or genre in the middle of the board. Have students suggest words or phrases related to the theme and list them on the board.

You may wish to provide students with a copy of various writing prompts to get them started. While this may mean that many students’ stories will have the same beginning, they will most likely arrive at dramatically different endings via dramatically different routes.

A bargain is at the centre of the relationship between the writer and the reader. That bargain is that the reader promises to suspend their disbelief as long as the writer creates a consistent and convincing fictional reality. Creating a believable world for the fictional characters to inhabit requires the student to draw on convincing details. The best way of doing this is through writing that appeals to the senses. Have your student reflect deeply on the world that they are creating. What does it look like? Sound like? What does the food taste like there? How does it feel like to walk those imaginary streets, and what aromas beguile the nose as the main character winds their way through that conjured market?

Also, Consider the when; or the time period. Is it a future world where things are cleaner and more antiseptic? Or is it an overcrowded 16th-century London with human waste stinking up the streets? If students can create a multi-sensory installation in the reader’s mind, then they have done this part of their job well.

Popular Settings from Children’s Literature and Storytelling

- Fairytale Kingdom

- Magical Forest

- Village/town

- Underwater world

- Space/Alien planet

2. CASTING THE CHARACTERS: THE WHO

Now that your student has created a believable world, it is time to populate it with believable characters.

In short stories, these worlds mustn’t be overpopulated beyond what the student’s skill level can manage. Short stories usually only require one main character and a few secondary ones. Think of the short story more as a small-scale dramatic production in an intimate local theater than a Hollywood blockbuster on a grand scale. Too many characters will only confuse and become unwieldy with a canvas this size. Keep it simple!

Creating believable characters is often one of the most challenging aspects of narrative writing for students. Fortunately, we can do a few things to help students here. Sometimes it is helpful for students to model their characters on actual people they know. This can make things a little less daunting and taxing on the imagination. However, whether or not this is the case, writing brief background bios or descriptions of characters’ physical personality characteristics can be a beneficial prewriting activity. Students should give some in-depth consideration to the details of who their character is: How do they walk? What do they look like? Do they have any distinguishing features? A crooked nose? A limp? Bad breath? Small details such as these bring life and, therefore, believability to characters. Students can even cut pictures from magazines to put a face to their character and allow their imaginations to fill in the rest of the details.

Younger students will often dictate to the reader the nature of their characters. To improve their writing craft, students must know when to switch from story-telling mode to story-showing mode. This is particularly true when it comes to character. Encourage students to reveal their character’s personality through what they do rather than merely by lecturing the reader on the faults and virtues of the character’s personality. It might be a small relayed detail in the way they walk that reveals a core characteristic. For example, a character who walks with their head hanging low and shoulders hunched while avoiding eye contact has been revealed to be timid without the word once being mentioned. This is a much more artistic and well-crafted way of doing things and is less irritating for the reader. A character who sits down at the family dinner table immediately snatches up his fork and starts stuffing roast potatoes into his mouth before anyone else has even managed to sit down has revealed a tendency towards greed or gluttony.

Understanding Character Traits

Again, there is room here for some fun and profitable prewriting activities. Give students a list of character traits and have them describe a character doing something that reveals that trait without ever employing the word itself.

It is also essential to avoid adjective stuffing here. When looking at students’ early drafts, adjective stuffing is often apparent. To train the student out of this habit, choose an adjective and have the student rewrite the sentence to express this adjective through action rather than telling.

When writing a story, it is vital to consider the character’s traits and how they will impact the story’s events. For example, a character with a strong trait of determination may be more likely to overcome obstacles and persevere. In contrast, a character with a tendency towards laziness may struggle to achieve their goals. In short, character traits add realism, depth, and meaning to a story, making it more engaging and memorable for the reader.

Popular Character Traits in Children’s Stories

- Determination

- Imagination

- Perseverance

- Responsibility

We have an in-depth guide to creating great characters here , but most students should be fine to move on to planning their conflict and resolution.

3. NO PROBLEM? NO STORY! HOW CONFLICT DRIVES A NARRATIVE

This is often the area apprentice writers have the most difficulty with. Students must understand that without a problem or conflict, there is no story. The problem is the driving force of the action. Usually, in a short story, the problem will center around what the primary character wants to happen or, indeed, wants not to happen. It is the hurdle that must be overcome. It is in the struggle to overcome this hurdle that events happen.

Often when a student understands the need for a problem in a story, their completed work will still not be successful. This is because, often in life, problems remain unsolved. Hurdles are not always successfully overcome. Students pick up on this.

We often discuss problems with friends that will never be satisfactorily resolved one way or the other, and we accept this as a part of life. This is not usually the case with writing a story. Whether a character successfully overcomes his or her problem or is decidedly crushed in the process of trying is not as important as the fact that it will finally be resolved one way or the other.

A good practical exercise for students to get to grips with this is to provide copies of stories and have them identify the central problem or conflict in each through discussion. Familiar fables or fairy tales such as Three Little Pigs, The Boy Who Cried Wolf, Cinderella, etc., are great for this.

While it is true that stories often have more than one problem or that the hero or heroine is unsuccessful in their first attempt to solve a central problem, for beginning students and intermediate students, it is best to focus on a single problem, especially given the scope of story writing at this level. Over time students will develop their abilities to handle more complex plots and write accordingly.

Popular Conflicts found in Children’s Storytelling.

- Good vs evil

- Individual vs society

- Nature vs nurture

- Self vs others

- Man vs self

- Man vs nature

- Man vs technology

- Individual vs fate

- Self vs destiny

Conflict is the heart and soul of any good story. It’s what makes a story compelling and drives the plot forward. Without conflict, there is no story. Every great story has a struggle or a problem that needs to be solved, and that’s where conflict comes in. Conflict is what makes a story exciting and keeps the reader engaged. It creates tension and suspense and makes the reader care about the outcome.

Like in real life, conflict in a story is an opportunity for a character’s growth and transformation. It’s a chance for them to learn and evolve, making a story great. So next time stories are written in the classroom, remember that conflict is an essential ingredient, and without it, your story will lack the energy, excitement, and meaning that makes it truly memorable.

4. THE NARRATIVE CLIMAX: HOW THINGS COME TO A HEAD!

The climax of the story is the dramatic high point of the action. It is also when the struggles kicked off by the problem come to a head. The climax will ultimately decide whether the story will have a happy or tragic ending. In the climax, two opposing forces duke things out until the bitter (or sweet!) end. One force ultimately emerges triumphant. As the action builds throughout the story, suspense increases as the reader wonders which of these forces will win out. The climax is the release of this suspense.

Much of the success of the climax depends on how well the other elements of the story have been achieved. If the student has created a well-drawn and believable character that the reader can identify with and feel for, then the climax will be more powerful.

The nature of the problem is also essential as it determines what’s at stake in the climax. The problem must matter dearly to the main character if it matters at all to the reader.

Have students engage in discussions about their favorite movies and books. Have them think about the storyline and decide the most exciting parts. What was at stake at these moments? What happened in your body as you read or watched? Did you breathe faster? Or grip the cushion hard? Did your heart rate increase, or did you start to sweat? This is what a good climax does and what our students should strive to do in their stories.

The climax puts it all on the line and rolls the dice. Let the chips fall where the writer may…

Popular Climax themes in Children’s Stories

- A battle between good and evil

- The character’s bravery saves the day

- Character faces their fears and overcomes them

- The character solves a mystery or puzzle.

- The character stands up for what is right.

- Character reaches their goal or dream.

- The character learns a valuable lesson.

- The character makes a selfless sacrifice.

- The character makes a difficult decision.

- The character reunites with loved ones or finds true friendship.

5. RESOLUTION: TYING UP LOOSE ENDS

After the climactic action, a few questions will often remain unresolved for the reader, even if all the conflict has been resolved. The resolution is where those lingering questions will be answered. The resolution in a short story may only be a brief paragraph or two. But, in most cases, it will still be necessary to include an ending immediately after the climax can feel too abrupt and leave the reader feeling unfulfilled.

An easy way to explain resolution to students struggling to grasp the concept is to point to the traditional resolution of fairy tales, the “And they all lived happily ever after” ending. This weather forecast for the future allows the reader to take their leave. Have the student consider the emotions they want to leave the reader with when crafting their resolution.

While the action is usually complete by the end of the climax, it is in the resolution that if there is a twist to be found, it will appear – think of movies such as The Usual Suspects. Pulling this off convincingly usually requires considerable skill from a student writer. Still, it may well form a challenging extension exercise for those more gifted storytellers among your students.

Popular Resolutions in Children’s Stories

- Our hero achieves their goal

- The character learns a valuable lesson

- A character finds happiness or inner peace.

- The character reunites with loved ones.

- Character restores balance to the world.

- The character discovers their true identity.

- Character changes for the better.

- The character gains wisdom or understanding.

- Character makes amends with others.

- The character learns to appreciate what they have.

Once students have completed their story, they can edit for grammar, vocabulary choice, spelling, etc., but not before!

As mentioned, there is a craft to storytelling, as well as an art. When accurate grammar, perfect spelling, and immaculate sentence structures are pushed at the outset, they can cause storytelling paralysis. For this reason, it is essential that when we encourage the students to write a story, we give them license to make mechanical mistakes in their use of language that they can work on and fix later.

Good narrative writing is a very complex skill to develop and will take the student years to become competent. It challenges not only the student’s technical abilities with language but also her creative faculties. Writing frames, word banks, mind maps, and visual prompts can all give valuable support as students develop the wide-ranging and challenging skills required to produce a successful narrative writing piece. But, at the end of it all, as with any craft, practice and more practice is at the heart of the matter.

TIPS FOR WRITING A GREAT NARRATIVE

- Start your story with a clear purpose: If you can determine the theme or message you want to convey in your narrative before starting it will make the writing process so much simpler.

- Choose a compelling storyline and sell it through great characters, setting and plot: Consider a unique or interesting story that captures the reader’s attention, then build the world and characters around it.

- Develop vivid characters that are not all the same: Make your characters relatable and memorable by giving them distinct personalities and traits you can draw upon in the plot.

- Use descriptive language to hook your audience into your story: Use sensory language to paint vivid images and sequences in the reader’s mind.

- Show, don’t tell your audience: Use actions, thoughts, and dialogue to reveal character motivations and emotions through storytelling.

- Create a vivid setting that is clear to your audience before getting too far into the plot: Describe the time and place of your story to immerse the reader fully.

- Build tension: Refer to the story map earlier in this article and use conflict, obstacles, and suspense to keep the audience engaged and invested in your narrative.

- Use figurative language such as metaphors, similes, and other literary devices to add depth and meaning to your narrative.

- Edit, revise, and refine: Take the time to refine and polish your writing for clarity and impact.

- Stay true to your voice: Maintain your unique perspective and style in your writing to make it your own.

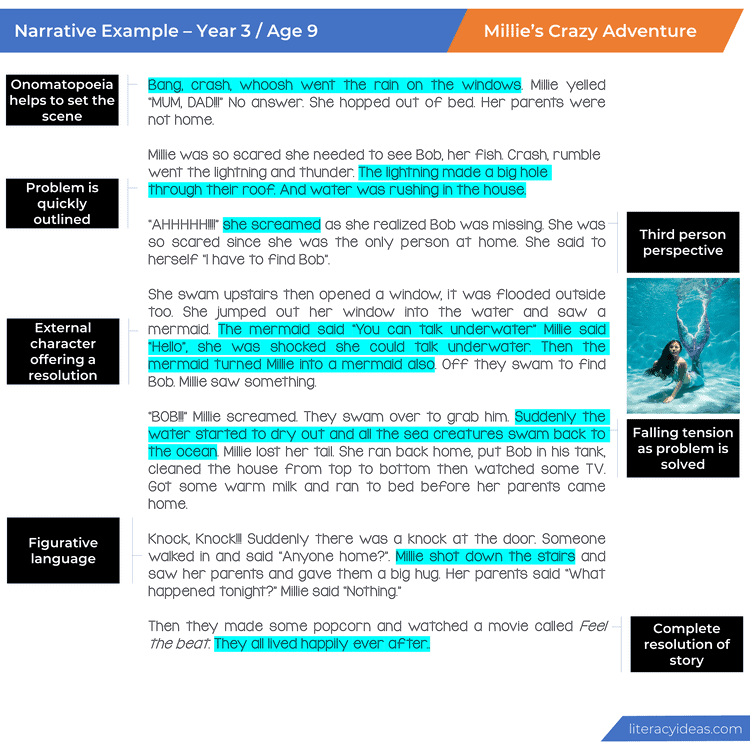

NARRATIVE WRITING EXAMPLES (Student Writing Samples)

Below are a collection of student writing samples of narratives. Click on the image to enlarge and explore them in greater detail. Please take a moment to read these creative stories in detail and the teacher and student guides which highlight some of the critical elements of narratives to consider before writing.

Please understand these student writing samples are not intended to be perfect examples for each age or grade level but a piece of writing for students and teachers to explore together to critically analyze to improve student writing skills and deepen their understanding of story writing.

We recommend reading the example either a year above or below, as well as the grade you are currently working with, to gain a broader appreciation of this text type.

NARRATIVE WRITING PROMPTS (Journal Prompts)

When students have a great journal prompt, it can help them focus on the task at hand, so be sure to view our vast collection of visual writing prompts for various text types here or use some of these.

- On a recent European trip, you find your travel group booked into the stunning and mysterious Castle Frankenfurter for a single night… As night falls, the massive castle of over one hundred rooms seems to creak and groan as a series of unexplained events begin to make you wonder who or what else is spending the evening with you. Write a narrative that tells the story of your evening.

- You are a famous adventurer who has discovered new lands; keep a travel log over a period of time in which you encounter new and exciting adventures and challenges to overcome. Ensure your travel journal tells a story and has a definite introduction, conflict and resolution.

- You create an incredible piece of technology that has the capacity to change the world. As you sit back and marvel at your innovation and the endless possibilities ahead of you, it becomes apparent there are a few problems you didn’t really consider. You might not even be able to control them. Write a narrative in which you ride the highs and lows of your world-changing creation with a clear introduction, conflict and resolution.

- As the final door shuts on the Megamall, you realise you have done it… You and your best friend have managed to sneak into the largest shopping centre in town and have the entire place to yourselves until 7 am tomorrow. There is literally everything and anything a child would dream of entertaining themselves for the next 12 hours. What amazing adventures await you? What might go wrong? And how will you get out of there scot-free?

- A stranger walks into town… Whilst appearing similar to almost all those around you, you get a sense that this person is from another time, space or dimension… Are they friends or foes? What makes you sense something very strange is going on? Suddenly they stand up and walk toward you with purpose extending their hand… It’s almost as if they were reading your mind.

NARRATIVE WRITING VIDEO TUTORIAL

Teaching Resources

Use our resources and tools to improve your student’s writing skills through proven teaching strategies.

When teaching narrative writing, it is essential that you have a range of tools, strategies and resources at your disposal to ensure you get the most out of your writing time. You can find some examples below, which are free and paid premium resources you can use instantly without any preparation.

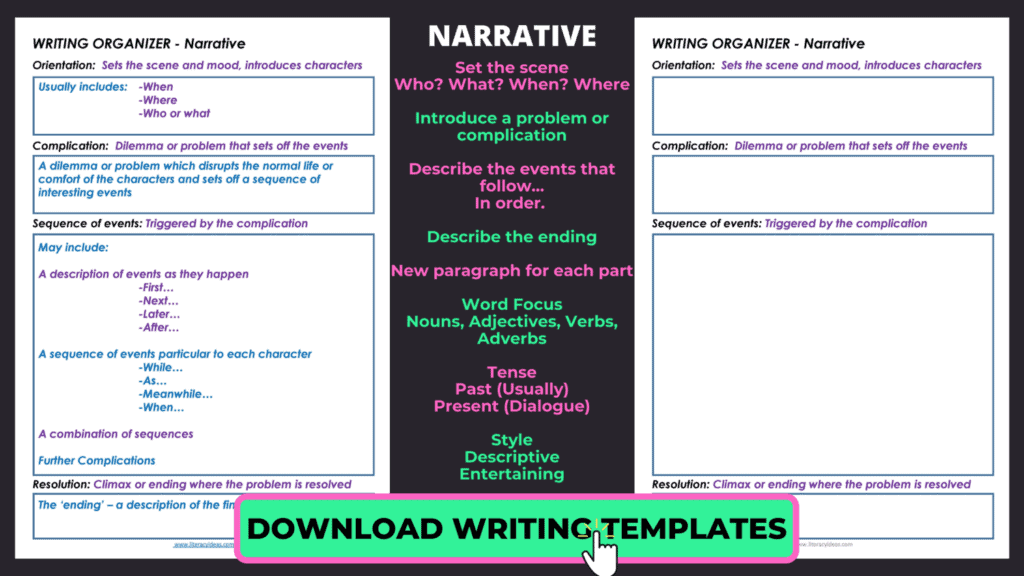

FREE Narrative Graphic Organizer

THE STORY TELLERS BUNDLE OF TEACHING RESOURCES

A MASSIVE COLLECTION of resources for narratives and story writing in the classroom covering all elements of crafting amazing stories. MONTHS WORTH OF WRITING LESSONS AND RESOURCES, including:

NARRATIVE WRITING CHECKLIST BUNDLE

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ (92 Reviews)

OTHER GREAT ARTICLES ABOUT NARRATIVE WRITING

Narrative Writing for Kids: Essential Skills and Strategies

7 Great Narrative Lesson Plans Students and Teachers Love

Top 7 Narrative Writing Exercises for Students

How to Write a Scary Story

Explore our Premium Teaching Unit on STORY WRITING

Elements of Creative Writing

(3 reviews)

J.D. Schraffenberger, University of Northern Iowa

Rachel Morgan, University of Northern Iowa

Grant Tracey, University of Northern Iowa

Copyright Year: 2023

ISBN 13: 9780915996179

Publisher: University of Northern Iowa

Language: English

Formats Available

Conditions of use.

Learn more about reviews.

Reviewed by Colin Rafferty, Professor, University of Mary Washington on 8/2/24

Fantastically thorough. By using three different authors, one for each genre of creative writing, the textbook allows for a wider diversity of thought and theory on writing as a whole, while still providing a solid grounding in the basics of each... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 5 see less

Fantastically thorough. By using three different authors, one for each genre of creative writing, the textbook allows for a wider diversity of thought and theory on writing as a whole, while still providing a solid grounding in the basics of each genre. The included links to referred texts also builds in an automatic, OER-based anthology for students. Terms are not only defined clearly, but also their utility is explained--here's what assonance can actually do in a poem, rather than simply "it's repeated vowel sounds,"

Content Accuracy rating: 5

Calling the content "accurate" requires a suspension of the notion that art and writing aren't subjective; instead, it might be more useful to judge the content on the potential usefulness to students, in which case it' s quite accurate. Reading this, I often found myself nodding in agreement with the authors' suggestions for considering published work and discussing workshop material, and their prompts for generating creative writing feel full of potential. It's as error-free, if not more so, than most OER textbooks (which is to say: a few typos here and there) and a surprising number of trade publications. It's not unbiased, per se--after all, these are literary magazine editors writing the textbook and often explaining what it is about a given piece of writing that they find (or do not find) engaging and admirable--but unbiased isn't necessarily a quantity one looks for in creative writing textbooks.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 4

The thing about creative writing is that they keep making more of it, so eventually the anthology elements of this textbook will be less "look what's getting published these days" and more "look what was getting published back then," but the structure of the textbook should allow for substitution and replacement (that said, if UNI pulls funding for NAR, as too many universities are doing these days, then the bigger concern is about the archive vanishing). The more rhetorical elements of the textbook are solid, and should be useful to students and faculty for a long time.

Clarity rating: 5

Very clear, straightforward prose, and perhaps more importantly, there's a sense of each author that emerges in each section, demonstrating to students that writing, especially creative writing, comes from a person. As noted above, any technical jargon is not only explained, but also discussed, meaning that how and why one might use any particular literary technique are emphasized over simply rote memorization of terms.

Consistency rating: 4

It's consistent within each section, but the voice and approach change with each genre. This is a strength, not a weakness, and allows the textbook to avoid the one-size-fits-all approach of single-author creative writing textbooks. There are different "try this" exercises for each genre that strike me as calibrated to impress the facets of that particular genre on the student.

Modularity rating: 5

The three-part structure of the book allows teachers to start wherever they like, genre-wise. While the internal structure of each section does build upon and refer back to earlier chapters, that seems more like an advantage than a disadvantage. Honestly, there's probably enough flexibility built into the textbook that even the callbacks could be glossed over quickly enough in the classroom.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 5

Chapters within each genre section build upon each other, starting with basics and developing the complexity and different elements of that genre. The textbook's overall organization allows some flexibility in terms of starting with fiction, poetry, or nonfiction.

Interface rating: 4

Easy to navigate. I particularly like the way that links for the anthology work in the nonfiction section (clearly appearing at the side of the text in addition to within it) and would like to see that consistently applied throughout.

Grammatical Errors rating: 5

A few typos here and there, but you know what else generally has a few typos here and there? Expensive physical textbooks.

Cultural Relevance rating: 5

The anthology covers a diverse array of authors and cultural identities, and the textbook authors are not only conscious of their importance but also discuss how those identities affect decisions that the authors might have made, even on a formal level. If you find an underrepresented group missing, it should be easy enough to supplement this textbook with a poem/essay/story.

Very excited to use this in my Intro to CW classes--unlike other OERs that I've used for the field, this one feels like it could compete with the physical textbooks head-to-head. Other textbooks have felt more like a trade-off between content and cost.

Reviewed by Jeanne Cosmos, Adjunct Faculty, Massachusetts Bay Community College on 7/7/24

Direct language and concrete examples & Case Studies. read more

Direct language and concrete examples & Case Studies.

References to literature and writers- on track.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 5

On point for support to assist writers and creative process.

Direct language and easy to read.

First person to third person. Too informal in many areas of the text.

Units are readily accessible.

Process of creative writing and prompts- scaffold areas of learning for students.

Interface rating: 5

No issues found.

The book is accurate in this regard.

Cultural Relevance rating: 4

Always could be revised and better.

Yes. Textbook font is not academic and spacing - also not academic. A bit too primary. Suggest- Times New Roman 12- point font & a space plus - Some of the language and examples too informal and the tone of lst person would be more effective if - direct and not so 'chummy' as author references his personal recollections. Not effective.

Reviewed by Robert Moreira, Lecturer III, University of Texas Rio Grande Valley on 3/21/24

Unlike Starkey's CREATIVE WRITING: FOUR GENRES IN BRIEF, this textbook does not include a section on drama. read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 4 see less

Unlike Starkey's CREATIVE WRITING: FOUR GENRES IN BRIEF, this textbook does not include a section on drama.

As far as I can tell, content is accurate, error free and unbiased.

The book is relevant and up-to-date.

The text is clear and easy to understand.

Consistency rating: 5

I would agree that the text is consistent in terms of terminology and framework.

Text is modular, yes, but I would like to see the addition of a section on dramatic writing.

Topics are presented in logical, clear fashion.

Navigation is good.

No grammatical issues that I could see.

Cultural Relevance rating: 3

I'd like to see more diverse creative writing examples.

As I stated above, textbook is good except that it does not include a section on dramatic writing.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter One: One Great Way to Write a Short Story

- Chapter Two: Plotting

- Chapter Three: Counterpointed Plotting

- Chapter Four: Show and Tell

- Chapter Five: Characterization and Method Writing

- Chapter Six: Character and Dialouge

- Chapter Seven: Setting, Stillness, and Voice

- Chapter Eight: Point of View

- Chapter Nine: Learning the Unwritten Rules

- Chapter One: A Poetry State of Mind

- Chapter Two: The Architecture of a Poem

- Chapter Three: Sound

- Chapter Four: Inspiration and Risk

- Chapter Five: Endings and Beginnings

- Chapter Six: Figurative Language

- Chapter Seven: Forms, Forms, Forms

- Chapter Eight: Go to the Image

- Chapter Nine: The Difficult Simplicity of Short Poems and Killing Darlings

Creative Nonfiction

- Chapter One: Creative Nonfiction and the Essay

- Chapter Two: Truth and Memory, Truth in Memory

- Chapter Three: Research and History

- Chapter Four: Writing Environments

- Chapter Five: Notes on Style

- Chapter Seven: Imagery and the Senses

- Chapter Eight: Writing the Body

- Chapter Nine: Forms

Back Matter

- Contributors

- North American Review Staff

Ancillary Material

- University of Northern Iowa

About the Book

This free and open access textbook introduces new writers to some basic elements of the craft of creative writing in the genres of fiction, poetry, and creative nonfiction. The authors—Rachel Morgan, Jeremy Schraffenberger, and Grant Tracey—are editors of the North American Review, the oldest and one of the most well-regarded literary magazines in the United States. They’ve selected nearly all of the readings and examples (more than 60) from writing that has appeared in NAR pages over the years. Because they had a hand in publishing these pieces originally, their perspective as editors permeates this book. As such, they hope that even seasoned writers might gain insight into the aesthetics of the magazine as they analyze and discuss some reasons this work is so remarkable—and therefore teachable. This project was supported by NAR staff and funded via the UNI Textbook Equity Mini-Grant Program.

About the Contributors

J.D. Schraffenberger is a professor of English at the University of Northern Iowa. He is the author of two books of poems, Saint Joe's Passion and The Waxen Poor , and co-author with Martín Espada and Lauren Schmidt of The Necessary Poetics of Atheism . His other work has appeared in Best of Brevity , Best Creative Nonfiction , Notre Dame Review , Poetry East , Prairie Schooner , and elsewhere.

Rachel Morgan is an instructor of English at the University of Northern Iowa. She is the author of the chapbook Honey & Blood , Blood & Honey . Her work is included in the anthology Fracture: Essays, Poems, and Stories on Fracking in American and has appeared in the Journal of American Medical Association , Boulevard , Prairie Schooner , and elsewhere.

Grant Tracey author of three novels in the Hayden Fuller Mysteries ; the chapbook Winsome featuring cab driver Eddie Sands; and the story collection Final Stanzas , is fiction editor of the North American Review and an English professor at the University of Northern Iowa, where he teaches film, modern drama, and creative writing. Nominated four times for a Pushcart Prize, he has published nearly fifty short stories and three previous collections. He has acted in over forty community theater productions and has published critical work on Samuel Fuller and James Cagney. He lives in Cedar Falls, Iowa.

Contribute to this Page

How to Structure a Story: The Fundamentals of Narrative - article

As children, we learned stories begin with "once upon a time" and end with "happily ever after." While this may be the most simplistic view of a story, it offers storytellers advice on a narrative structure that stands the test of time.

A good book has a beginning, middle, and end—but a good storyteller knows it’s not always that simple. Getting from beginning to end requires you to follow a certain structure in order to create an engaging and exciting experience for the reader.

What is Narrative Structure?

Narrative structure, also referred to as a storyline or plotline, describes the framework of how one tells a story. It's how a book is organized and how the plot is unveiled to the reader.

Most stories revolve around a single question that represent the core of the story. Will Harry potter defeat Voldemort? Will Romeo and Juliet end up together? Will Frodo destroy the Ring?

The series of events that follow in an attempt to answer this defining question is what creates your narrative structure.

Various components work together to build a narrative structure , but it’s mostly centered around the development of your plot and your main character(s).

Types of Narrative Structure

Linear/Chronological : When the author tells a story in chronological order. This structure can include flashbacks, but the majority of the narrative is told in the order that it occurs. Most books tend to fall under this narrative structure.

Nonlinear/Fractured : A nonlinear structure tells the story out of chronological order, jumping disjointedly through the timeline. David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas is an example of this narrative structure, as it switches between multiple characters at different points in time.

Circular : In a circular narrative, the story ends where it began. Although the starting and ending points are the same, the character(s) undergo a transformation, affected by the story's events. S.E. Hinton’s The Outsiders is an example of circular narrative structure.

Parallel : In parallel structure, the story follows multiple storylines, which are tied together through an event, character, or theme. F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby or the movie Finding Nemo are both examples of this structure.

Interactive : The reader makes choices throughout the interactive narrative, leading to new options and alternate endings. These stories are most prominent as "choose your own adventure" books.

Types of Narrative Arcs for Plot Development

Regardless which narrative structure you choose, one of the biggest components to creating a great storyline or narrative structure is developing your plot . These are all the actions that will take place in the book, culminating in an interesting and satisfying ending.

These structures are often considered “arcs” because of the way a story rises and falls, creating an arc shape. The most fundamental narrative arc includes the following five plot stages:

Exposition : This is your introduction, where you introduce the characters, establish the setting, and present the primary conflict.

Rising action : This second stage is where you introduce the primary conflict and set the story in motion. Each succeeding event should be more complicated than the previous, creating tension and excitement as the story builds.

Climax : This is the turning point in the story—the point of the highest tension and conflict. This is the moment that should leave the reader wondering what’s next.

Falling action : In this stage, the story begins to calm down and work toward a satisfying ending. Loose ends are tied up, explanations are revealed, and the reader learns more about how the conflict is resolved.

Resolution : The main conflict gets resolved and the story ends.

This narrative arc is the most basic framework for developing a book’s plot. Although you can vary it slightly, your story should follow this basic structure.

However, more comprehensive frameworks exist if you need extra help developing a plot.

The 3 Act, 8 Sequence structure is used by both authors and screenwriters alike to develop an engaging storyline.

Act 1 – The Beginning

Sequence 1 – Status Quo and Inciting Incident: Established the main character in his/her normal life, ending with a point that sets the story into motion.

Sequence 2 – Predicament and Lock-In: Sets up the central conflict of the story and the main character accepts the call to action.

Act 2 – The Middle

Sequence 3 – First Obstacle: The character faces the first obstacles toward reaching their goal, building the tension and putting them at a point of no return.

Sequence 4 – Midpoint: A decisive moment where the main character faces the central conflict in some way, usually realizing something that changes him/her.

Sequence 5 – Rising Action: Continue to raise the stakes for your main character, usually with a subplot of some sort that builds up to the main conflict.

Sequence 6 –Biggest Obstacle: The main conflict or the highest point of tension in your story. This should be the most difficult moment for your character, so make it count.

Act 3 – The End

Sequence 7 – Twist: Here, your character deals with the remnants of the main conflict or realized a new goal they have to achieve.

Sequence 8 – Resolution: Where you’ll give the answer to your story’s main question, thus resolving the conflict and bringing your story to a satisfying close (or a cliffhanger, if you’re writing a series).

As you can see, this narrative structure follows a very similar pattern as the basic five-element framework, but it can provide you with a little more information and guidance as you work to build out your plot.

Types of Emotional Arcs for Character Development

The second component to creating a narrative structure is the process of how your main character will develop and change from the beginning to the end of your story.

While a good story will have both a plot and character arc, most are driven primarily by one or the other.

If your story’s question revolves around a physical or external goal, such as Harry Potter defeating Voldemort, then that story will be mostly plot-driven.

On the other hand, character-driven stories will feature more emotional arcs. These stories aim to answer an internal question, such as J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye, which deals with the main character, Holden Caulfield, going through the loss of childhood innocence.

But things aren’t always so black and white. Many stories that seem plot-driven on the surface have very strong character arcs running through them.

That’s because every good story has a protagonist and an antagonist with strong goals, and whether or not they achieve those goal plays a large part in the narrative structure.

As long as your character has a strong desire or motivation to drive them , and that motivation plays a role in the plot, you have a character arc.

Ultimately, character-driven narrative structures fall into three categories: positive, negative, and static.

Positive or Growth Character Arcs

Positive narrative arcs are when throughout the story, the main character overcomes a flaw, fear, or false belief and ultimately becomes a better person by the end.

Let’s take a look at this character arc within the framework of the 8-sequence narrative structure.

- Sequence 1 – Status Quo and Inciting Incident: Shows the character in their normal world until something shakes it up, causing a desire to emerge

- Sequence 2 – Predicament and Lock-In: The character realizes he/she must change to reach their goal

- Sequence 3 – First Obstacle: He/she faces a conflict that challenges his/her belief

- Sequence 4 – Midpoint: The main character begins to take initiative to confront their flaws and fears

- Sequence 5 – Rising Action: Realizing something from their past or a secret, the reader gets a glimpse into why the main character holds this false belief, but the main character isn’t quite ready to fix it yet

- Sequence 6 –Biggest Obstacle: Something causes the protagonist to realize the truth, giving them the advantage to overcome the antagonist and fight the problem head-on

- Sequence 7/8 – Twist/Resolution: The main character has officially changed for the better

Elizabeth Bennett’s character Pride and Prejudice and Nick Carraway from The Great Gatsby are some examples of the growth character arc.

Negative or Tragic Character Arcs

Negative narrative arcs occur when the main character holds some sort of flaw, desire, or false belief that ultimately leads to their downfall.

Let’s take a look at this character arc within the framework of the 8 sequence structure.

- Sequence 1 – Status Quo and Inciting Incident: Shows the character in their normal world until something shakes it up, causing them either to eagerly pursue a desire or forced into a circumstance

- Sequence 2 – Predicament and Lock-In: The character takes an action that seems promising, but will ultimately cause a negative change within them

- Sequence 3 – First Obstacle: Their beliefs are rattled, but they manage to cling to their false desire

- Sequence 4 – Midpoint: The character is confronted with an undeniable reality…

- Sequence 5 – Rising Action: … but chooses instead to fling themselves further into their desire regardless of knowing better

- Sequence 6 –Biggest Obstacle: Your character reaches a breaking point, but chooses instead to pursue their false desire with reckless abandon

- Sequence 7/8 – Twist/Resolution: The character either achieves a goal (twist) or fails to achieve anything, resulting in a tragic ending, which is often death

Gatsby’s character from The Great Gatsby, Walter White from Breaking Bad, and Darth Vader from Star Wars are all examples of the tragic character arc.

Static Character Arcs

Static narrative arcs are when the main character’s morals and beliefs are challenged, but they ultimately hold true to themselves through the end.

- Sequence 1 – Status Quo and Inciting Incident: The main character is his/her normal world

- Sequence 2 – Predicament and Lock-In: The main character’s world is turned upside down

- Sequence 3 – First Obstacle: They are forced into a new journey with unavoidable conflicts

- Sequence 4 – Midpoint: The character gains some skill he/she needs to change the stakes, and now they begin actively engaging in conflict to defeat the antagonist

- Sequence 5 – Rising Action: The main character suffers a major defeat or breaking point, but they manage to find a spark of hope or opportunity

- Sequence 6 –Biggest Obstacle: The final showdown between the protagonist and antagonist

- Sequence 7/8 – Twist/Resolution: The antagonist is defeated and the main character stands firm in his/her truth

Harry Potter, Katniss Everdeen from The Hunger Games, and Bilbo Baggins in The Hobbit are all examples of a static character arc.

Building a Narrative Structure

As you can see, these character arcs easily fall in-line with the plot narrative structure. Some books even tend to have multiple characters experiencing different character arcs on top of the plot structure.

It may take some time to work everything out, but taking the time to work through your plot and character arcs will go a long way to ensure you’re writing an engaging and exciting story.

First, try to decide if your story will be mostly plot-driven or character-driven. If you feel stuck, use these questions to help you figure it out:

- What is your protagonist’s goal? Is it external, like defeating a villain? Or is it internal, like overcoming a deeply-held belief?

- How about your antagonist?

- Will your story be centered around specific events of conflict that move your story forward? Or are they more focused on the personal, internal struggle of your character(s)?

- When you set out to write a story, what comes to mind first, a riveting plot or a cast of compelling characters?

This exercise is merely to help you understand which of the two takes precedence in your story—not which one you follow and which one you ignore.

Often, the decision between a plot-driven or character-driven story will come down to personal preference. Which is most appealing to you? Then, the one you don’t choose will just become secondary.

Plot-Driven Narratives

When your focus is on plot, you should pay special attention to the events that will occur in your story.

Plot-driven narratives are exciting, action-packed , and fast-paced. They compel the reader to keep reading just to find out what will happen next.

When writing a plot-driven story, make sure all your plot points tie together seamlessly to create a full narrative structure. As you focus on events, it’s easy to forget about the characters and their motivations.

Remember: your story isn’t about things that are happening to the character, it’s about how your character is reacting to and participating in these events.

While many of these events may be out of your character’s control, they should still have an active role within them.

In every scene, you should be asking yourself these questions:

- What is my character’s motivation?

- Why is he/she making this decision and not another one?

- What in the character’s background led them to make this decision?

As a result, your characters will tie into your plot arc.

Character-Driven Narratives

When your story’s focus is on characters, you should explore how a character arrives at a particular choice.

Character-driven narratives tend to focus more on internal conflicts than external ones, such as the internal or interpersonal struggle of the character(s).

When writing a character-driven story, make sure you’re putting extra attention toward developing interesting, realistic, and charismatic characters . The true test of a good character-driven story is one where the reader feels a deep, emotional connection to your characters.

Your plot may be simple—used less to create action and more to further develop the character’s arc—but you still need to make sure your characters are actually doing something.

The main character should interact with others and their environment, and these things should shape your character in some way.

Put your character in situations that show the reader who they truly are. Test them. Make things difficult.

- What’s the worst thing that can happen to my character right now?

- If I throw it at them, how would they respond?

As a result, your plot will tie in to your character’s narrative arc.

- Literary Fiction

- Daniel Southerland</a> and <span class="who-likes">5 others</span> like this" data-format="<span class="count"><span class="icon"></span>{count}</span>" data-configuration="Format=%3Cspan%20class%3D%22count%22%3E%3Cspan%20class%3D%22icon%22%3E%3C%2Fspan%3E%7Bcount%7D%3C%2Fspan%3E&IncludeTip=true&LikeTypeId=00000000-0000-0000-0000-000000000000" >

Agreed with Ruben, amazing!

Thank you Ruben

I am attempting to write my first book. It didn't come to me in a dream, but the content of my book will be about real life experiences. The problem for me is that I have so much information that I think I will need to find a way to organize the information so that will flow, be meaningful, and identifying to its audience, so that it will hold their attention.

Very nice insight, and very interesting. I'm currently writing my second book. , Now let me forewarn you, I've never studied literature or even delved in to the art of story writing. My story came to me as in a dream and from there i started writing, not having a clue as to what I was doing, To be honest. I don't know what I'm doing. you could say. however reading your article I discovered that in my book are contained Icarus, Oedipus and man in the hole. my book is more about a woman's trials and tribulations. .And it just happened they are in that same order. except that my character will rise at the end. Thank you for sharing such valuable information. Now I know that despite needing much help i am at least following some order that I hadn't even known existed. Again thank you.

- Ruben Elizardo</a> likes this" data-format="{count}" data-configuration="Format=%7Bcount%7D&IncludeTip=true&LikeTypeId=00000000-0000-0000-0000-000000000000" >

© Copyright 2018 Author Learning Center. All Rights Reserved

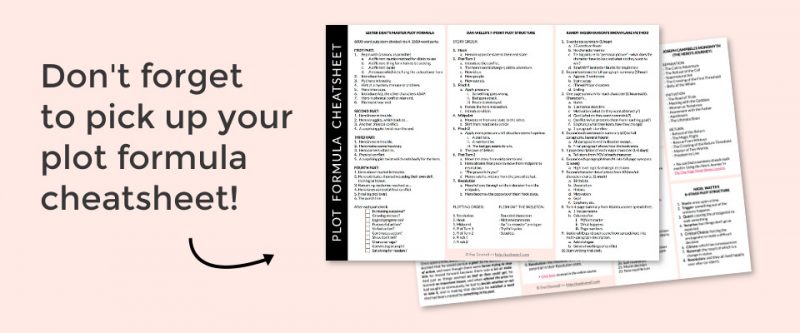

How to Use Plot Formulas

If you’re a new writer, a plot structure or plot formula is your shortcut to writing a great story. A plotting method can…

- Help you get an overview of your story.

- Help you figure out where to begin and end your story.

- Help you decide what happens next .

- Help you keep on track , know where you are, and how far you still have to go.

- Help you find and fix weak points in your story.

- Speed up the processes of plotting, writing, and editing.

Many writers, especially prolific writers of genre fiction, use plot formulas, and I think even those who don’t profess to pre-planning, possess an innate sense of how to structure a story so that it’s effective and powerful .

If you’re a new writer, or a writer who’s struggling to complete a writing project, then studying plot structure can help you gain mastery over your storytelling.

Why I ♥ plot structure & plot formulas:

- They simplify something that can be very complicated and overwhelming.

- I love the idea of a universal story that unites us all.

- They help me turn ideas into stories fast (and the faster I progress with a project, the less likely I am to flake out).

- I love to (try to) understand how things work .