The Ultimate Guide to Qualitative Research - Part 3: Presenting Qualitative Data

- Introduction

How do you present qualitative data?

Data visualization.

- Research paper writing

- Transparency and rigor in research

- How to publish a research paper

Table of contents

- Transparency and rigor

Navigate to other guide parts:

Part 1: The Basics or Part 2: Handling Qualitative Data

- Presenting qualitative data

In the end, presenting qualitative research findings is just as important a skill as mastery of qualitative research methods for the data collection and data analysis process . Simply uncovering insights is insufficient to the research process; presenting a qualitative analysis holds the challenge of persuading your audience of the value of your research. As a result, it's worth spending some time considering how best to report your research to facilitate its contribution to scientific knowledge.

When it comes to research, presenting data in a meaningful and accessible way is as important as gathering it. This is particularly true for qualitative research , where the richness and complexity of the data demand careful and thoughtful presentation. Poorly written research is taken less seriously and left undiscussed by the greater scholarly community; quality research reporting that persuades its audience stands a greater chance of being incorporated in discussions of scientific knowledge.

Qualitative data presentation differs fundamentally from that found in quantitative research. While quantitative data tend to be numerical and easily lend themselves to statistical analysis and graphical representation, qualitative data are often textual and unstructured, requiring an interpretive approach to bring out their inherent meanings. Regardless of the methodological approach , the ultimate goal of data presentation is to communicate research findings effectively to an audience so they can incorporate the generated knowledge into their research inquiry.

As the section on research rigor will suggest, an effective presentation of your research depends on a thorough scientific process that organizes raw data into a structure that allows for a thorough analysis for scientific understanding.

Preparing the data

The first step in presenting qualitative data is preparing the data. This preparation process often begins with cleaning and organizing the data. Cleaning involves checking the data for accuracy and completeness, removing any irrelevant information, and making corrections as needed. Organizing the data often entails arranging the data into categories or groups that make sense for your research framework.

Coding the data

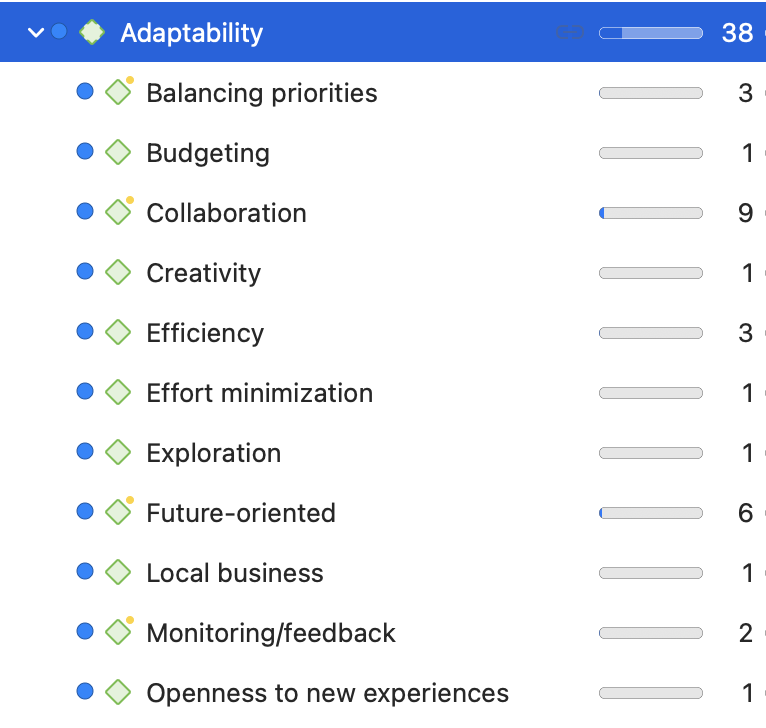

Once the data are cleaned and organized, the next step is coding , a crucial part of qualitative data analysis. Coding involves assigning labels to segments of the data to summarize or categorize them. This process helps to identify patterns and themes in the data, laying the groundwork for subsequent data interpretation and presentation. Qualitative research often involves multiple iterations of coding, creating new and meaningful codes while discarding unnecessary ones , to generate a rich structure through which data analysis can occur.

Uncovering insights

As you navigate through these initial steps, keep in mind the broader aim of qualitative research, which is to provide rich, detailed, and nuanced understandings of people's experiences, behaviors, and social realities. These guiding principles will help to ensure that your data presentation is not only accurate and comprehensive but also meaningful and impactful.

While this process might seem intimidating at first, it's an essential part of any qualitative research project. It's also a skill that can be learned and refined over time, so don't be discouraged if you find it challenging at first. Remember, the goal of presenting qualitative data is to make your research findings accessible and understandable to others. This requires careful preparation, a clear understanding of your data, and a commitment to presenting your findings in a way that respects and honors the complexity of the phenomena you're studying.

In the following sections, we'll delve deeper into how to create a comprehensive narrative from your data, the visualization of qualitative data , and the writing and publication processes . Let's briefly excerpt some of the content in the articles in this part of the guide.

ATLAS.ti helps you make sense of your data

Find out how with a free trial of our powerful data analysis interface.

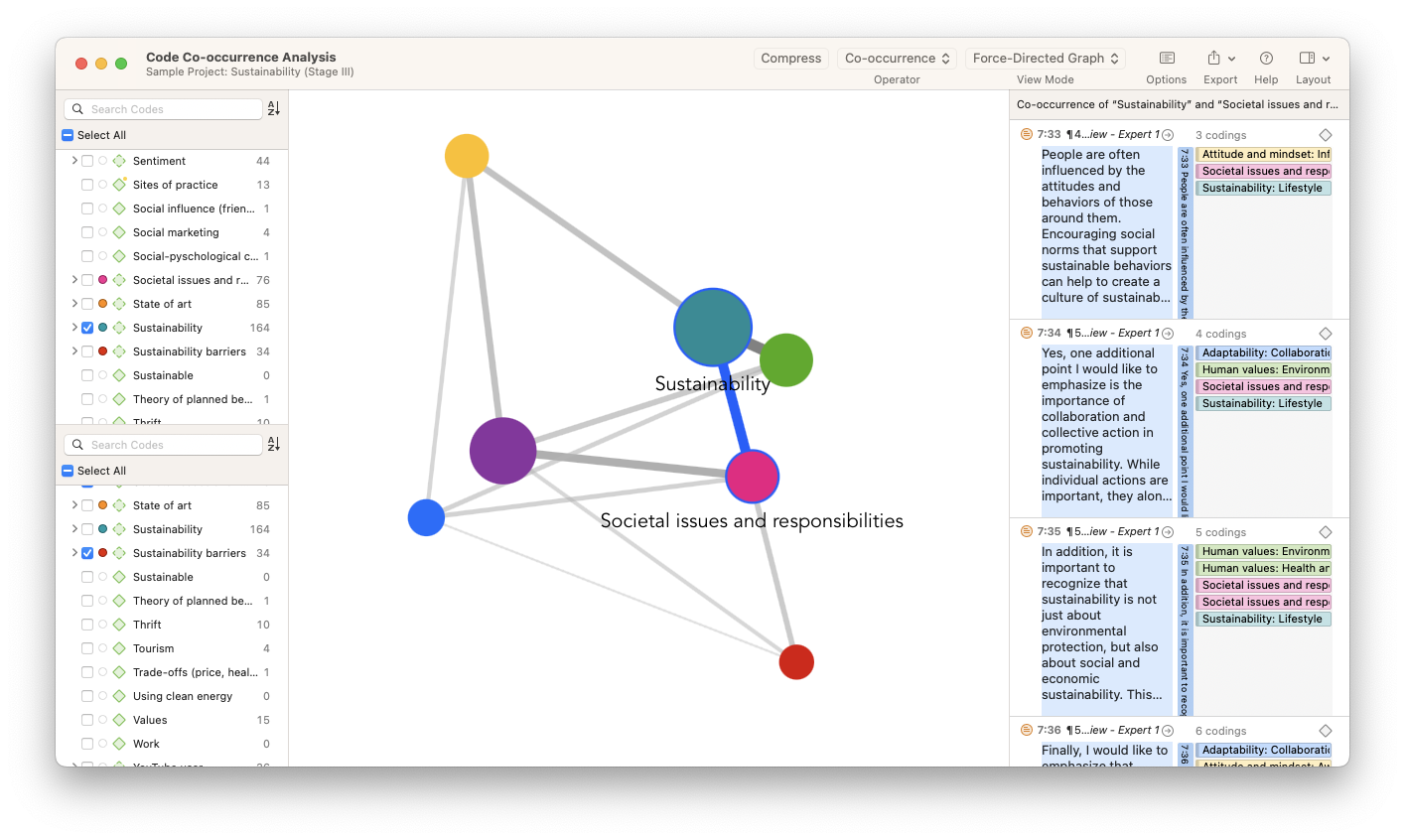

How often do you read a research article and skip straight to the tables and figures? That's because data visualizations representing qualitative and quantitative data have the power to make large and complex research projects with thousands of data points comprehensible when authors present data to research audiences. Researchers create visual representations to help summarize the data generated from their study and make clear the pathways for actionable insights.

In everyday situations, a picture is always worth a thousand words. Illustrations, figures, and charts convey messages that words alone cannot. In research, data visualization can help explain scientific knowledge, evidence for data insights, and key performance indicators in an orderly manner based on data that is otherwise unstructured.

For all of the various data formats available to researchers, a significant portion of qualitative and social science research is still text-based. Essays, reports, and research articles still rely on writing practices aimed at repackaging research in prose form. This can create the impression that simply writing more will persuade research audiences. Instead, framing research in terms that are easy for your target readers to understand makes it easier for your research to become published in peer-reviewed scholarly journals or find engagement at scholarly conferences. Even in market or professional settings, data visualization is an essential concept when you need to convince others about the insights of your research and the recommendations you make based on the data.

Importance of data visualization

Data visualization is important because it makes it easy for your research audience to understand your data sets and your findings. Also, data visualization helps you organize your data more efficiently. As the explanation of ATLAS.ti's tools will illustrate in this section, data visualization might point you to research inquiries that you might not even be aware of, helping you get the most out of your data. Strictly speaking, the primary role of data visualization is to make the analysis of your data , if not the data itself, clear. Especially in social science research, data visualization makes it easy to see how data scientists collect and analyze data.

Prerequisites for generating data visualizations

Data visualization is effective in explaining research to others only if the researcher or data scientist can make sense of the data in front of them. Traditional research with unstructured data usually calls for coding the data with short, descriptive codes that can be analyzed later, whether statistically or thematically. These codes form the basic data points of a meaningful qualitative analysis . They represent the structure of qualitative data sets, without which a scientific visualization with research rigor would be extremely difficult to achieve. In most respects, data visualization of a qualitative research project requires coding the entire data set so that the codes adequately represent the collected data.

A successfully crafted research study culminates in the writing of the research paper . While a pilot study or preliminary research might guide the research design , a full research study leads to discussion that highlights avenues for further research. As such, the importance of the research paper cannot be overestimated in the overall generation of scientific knowledge.

The physical and natural sciences tend to have a clinical structure for a research paper that mirrors the scientific method: outline the background research, explain the materials and methods of the study, outline the research findings generated from data analysis, and discuss the implications. Qualitative research tends to preserve much of this structure, but there are notable and numerous variations from a traditional research paper that it's worth emphasizing the flexibility in the social sciences with respect to the writing process.

Requirements for research writing

While there aren't any hard and fast rules regarding what belongs in a qualitative research paper , readers expect to find a number of pieces of relevant information in a rigorously-written report. The best way to know what belongs in a full research paper is to look at articles in your target journal or articles that share a particular topic similar to yours and examine how successfully published papers are written.

It's important to emphasize the more mundane but equally important concerns of proofreading and formatting guidelines commonly found when you write a research paper. Research publication shouldn't strictly be a test of one's writing skills, but acknowledging the importance of convincing peer reviewers of the credibility of your research means accepting the responsibility of preparing your research manuscript to commonly accepted standards in research.

As a result, seemingly insignificant things such as spelling mistakes, page numbers, and proper grammar can make a difference with a particularly strict reviewer. Even when you expect to develop a paper through reviewer comments and peer feedback, your manuscript should be as close to a polished final draft as you can make it prior to submission.

Qualitative researchers face particular challenges in convincing their target audience of the value and credibility of their subsequent analysis. Numbers and quantifiable concepts in quantitative studies are relatively easier to understand than their counterparts associated with qualitative methods . Think about how easy it is to make conclusions about the value of items at a store based on their prices, then imagine trying to compare those items based on their design, function, and effectiveness.

Qualitative research involves and requires these sorts of discussions. The goal of qualitative data analysis is to allow a qualitative researcher and their audience to make such determinations, but before the audience can accept these determinations, the process of conducting research that produces the qualitative analysis must first be seen as trustworthy. As a result, it is on the researcher to persuade their audience that their data collection process and subsequent analysis is rigorous.

Qualitative rigor refers to the meticulousness, consistency, and transparency of the research. It is the application of systematic, disciplined, and stringent methods to ensure the credibility, dependability, confirmability, and transferability of research findings. In qualitative inquiry, these attributes ensure the research accurately reflects the phenomenon it is intended to represent, that its findings can be understood or used by others, and that its processes and results are open to scrutiny and validation.

Transparency

It is easier to believe the information presented to you if there is a rigorous analysis process behind that information, and if that process is explicitly detailed. The same is true for qualitative research results, making transparency a key element in qualitative research methodologies. Transparency is a fundamental aspect of rigor in qualitative research. It involves the clear, detailed, and explicit documentation of all stages of the research process. This allows other researchers to understand, evaluate, replicate, and build upon the study. Transparency in qualitative research is essential for maintaining rigor, trustworthiness, and ethical integrity. By being transparent, researchers allow their work to be scrutinized, critiqued, and improved upon, contributing to the ongoing development and refinement of knowledge in their field.

Research papers are only as useful as their audience in the scientific community is wide. To reach that audience, a paper needs to pass the peer review process of an academic journal. However, the idea of having research published in peer-reviewed journals may seem daunting to newer researchers, so it's important to provide a guide on how an academic journal looks at your research paper as well as how to determine what is the right journal for your research.

In simple terms, a research article is good if it is accepted as credible and rigorous by the scientific community. A study that isn't seen as a valid contribution to scientific knowledge shouldn't be published; ultimately, it is up to peers within the field in which the study is being considered to determine the study's value. In established academic research, this determination is manifest in the peer review process. Journal editors at a peer-reviewed journal assign papers to reviewers who will determine the credibility of the research. A peer-reviewed article that completed this process and is published in a reputable journal can be seen as credible with novel research that can make a profound contribution to scientific knowledge.

The process of research publication

The process has been codified and standardized within the scholarly community to include three main stages. These stages include the initial submission stage where the editor reviews the relevance of the paper, the review stage where experts in your field offer feedback, and, if reviewers approve your paper, the copyediting stage where you work with the journal to prepare the paper for inclusion in their journal.

Publishing a research paper may seem like an opaque process where those involved with academic journals make arbitrary decisions about the worthiness of research manuscripts. In reality, reputable publications assign a rubric or a set of guidelines that reviewers need to keep in mind when they review a submission. These guidelines will most likely differ depending on the journal, but they fall into a number of typical categories that are applicable regardless of the research area or the type of methods employed in a research study, including the strength of the literature review , rigor in research methodology , and novelty of findings.

Choosing the right journal isn't simply a matter of which journal is the most famous or has the broadest reach. Many universities keep lists of prominent journals where graduate students and faculty members should publish a research paper , but oftentimes this list is determined by a journal's impact factor and their inclusion in major academic databases.

Guide your research to publication with ATLAS.ti

Turn insights into visualizations with our easy-to-use interface. Download a free trial today.

This section is part of an entire guide. Use this table of contents to jump to any page in the guide.

Part 1: The Basics

- What is qualitative data?

- 10 examples of qualitative data

- Qualitative vs. quantitative research

- What is mixed methods research?

- Theoretical perspective

- Theoretical framework

- Literature reviews

- Research questions

- Conceptual framework

- Conceptual vs. theoretical framework

- Focus groups

- Observational research

- Case studies

- Survey research

- What is ethnographic research?

- Confidentiality and privacy in research

- Bias in research

- Power dynamics in research

- Reflexivity

Part 2: Handling Qualitative Data

- Research transcripts

- Field notes in research

- Research memos

- Survey data

- Images, audio, and video in qualitative research

- Coding qualitative data

- Coding frame

- Auto-coding and smart coding

- Organizing codes

- Content analysis

- Thematic analysis

- Thematic analysis vs. content analysis

- Narrative research

- Phenomenological research

- Discourse analysis

- Grounded theory

- Deductive reasoning

- What is inductive reasoning?

- Inductive vs. deductive reasoning

- What is data interpretation?

- Qualitative analysis software

Part 3: Presenting Qualitative Data

- Data visualization - What is it and why is it important?

COMMENTS

Don't make the reader do the analytic work for you. Now, on to some specific ways to structure your findings section. 1). Tables. Tables can be used to give an overview of what you're about to present in your findings, including the themes, some supporting evidence, and the meaning/explanation of the theme.

Reporting & Presenting Interview Findings. In qualitative research, reporting interview findings is a critical step in showcasing the depth and richness of the data collected. It is about presenting what participants said and interpreting and organizing the information in a way that highlights key insights.

In this video, I explain how to present and discuss findings in qualitative research. I discuss the use of visual representations (e.g. diagrams, charts, etc...

1 Answer to this question. Answer: Analyzing and presenting qualitative data in a research paper can be difficult. The Methods section is where one needs to justify and present the research design. As you have rightly said, there are stipulations on the word count for a manuscript. To present the interview data, you can consider using a table.

3l - A Guide toPresenting Qualitative DataNumerical data naturally lends itself to a wide range of different data presentation techniques and good researchers exploit a larg. number of these within any particular study. It is tempting to ignore the qualitative data of an investigation, such as interview transcripts and observations, until the ...

To present interviews in a dissertation, you first need to transcribe your interviews. You can use transcription software for this. You can then add the written interviews to the appendix. If you have many or long interviews that make the appendix extremely long, the appendix (after consultation with the supervisor) can be submitted as a ...

The results chapter in a dissertation or thesis (or any formal academic research piece) is where you objectively and neutrally present the findings of your qualitative analysis (or analyses if you used multiple qualitative analysis methods). This chapter can sometimes be combined with the discussion chapter (where you interpret the data and ...

Qualitative research presents "best examples" of raw data to demonstrate an analytic point, not simply to display data. Numbers (descriptive statistics) help your reader understand how prevalent or typical a finding is. Numbers are helpful and should not be avoided simply because this is a qualitative dissertation.

TIPSHEET QUALITATIVE INTERVIEWINGTIP. HEET - QUALITATIVE INTERVIEWINGQualitative interviewing provides a method for collecting rich and detailed information about how individuals experience, understand. nd explain events in their lives. This tipsheet offers an introduction to the topic and some advice on. arrying out eff.

Preparing the data. The first step in presenting qualitative data is preparing the data. This preparation process often begins with cleaning and organizing the data. Cleaning involves checking the data for accuracy and completeness, removing any irrelevant information, and making corrections as needed.