Hedy Lamarr

Hedy Lamarr was an Austrian American actress during MGM's "Golden Age" who also left her mark on technology. She helped develop an early technique for spread spectrum communications.

(1914-2000)

Who Was Hedy Lamarr?

Hedy Lamarr was an actress during MGM's "Golden Age." She starred in such films as Tortilla Flat, Lady of the Tropics, Boom Town and Samson and Delilah , with the likes of Clark Gable and Spencer Tracey. Lamarr was also a scientist, co-inventing an early technique for spread spectrum communications — the key to many wireless communications of our present day. A recluse later in life, Lamarr died in her Florida home in 2000.

Lamarr was born Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler on November 9, 1914, in Vienna, Austria. Discovered by an Austrian film director as a teenager, she gained international notice in 1933, with her role in the sexually charged Czech film Ecstasy . After her unhappy marriage ended with Fritz Mandl, a wealthy Austrian munitions manufacturer who sold arms to the Nazis, she fled to the United States and signed a contract with the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studio in Hollywood under the name Hedy Lamarr. Upon the release of her first American film, Algiers , co-starring Charles Boyer, Lamarr became an immediate box-office sensation.

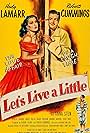

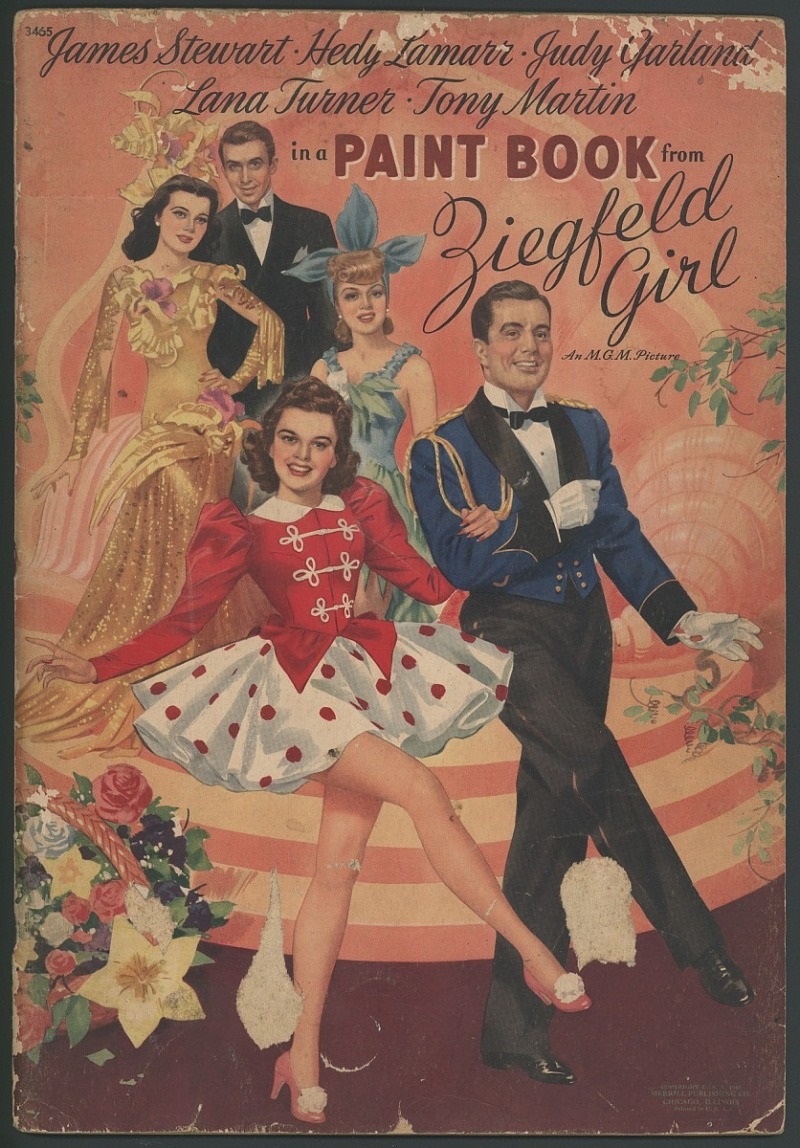

Often referred to as one of the most gorgeous and exotic of Hollywood's leading ladies, Lamarr made a number of well-received films during the 1930s and 1940s. Notable among them were Lady of the Tropics (1939), co-starring Robert Taylor; Boom Town (1940), with Clark Gable and Spencer Tracy; Tortilla Flat (1942), co-starring Tracy; and Samson and Delilah (1949), opposite Victor Mature. She was reportedly producer Hal Wallis's first choice for the heroine in his classic 1943 film, Casablanca , a part that eventually went to Ingrid Bergman .

'Secret Communications System'

In 1942, during the heyday of her career, Lamarr earned recognition in a field quite different from entertainment. She and her friend, the composer George Antheil, received a patent for an idea of a radio signaling device, or "Secret Communications System," which was a means of changing radio frequencies to keep enemies from decoding messages. Originally designed to defeat the German Nazis, the system became an important step in the development of technology to maintain the security of both military communications and cellular phones.

Lamarr wasn't instantly recognized for her communications invention since its wide-ranging impact wasn't understood until decades later. However, in 1997, Lamarr and Antheil were honored with the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) Pioneer Award, and that same year Lamarr became the first female to receive the BULBIE™ Gnass Spirit of Achievement Award, considered the "Oscars" of inventing.

Later Career

Lamarr's film career began to decline in the 1950s; her last film was 1958's The Female Animal , with Jane Powell. In 1966, she published a steamy best-selling autobiography, Ecstasy and Me , but later sued the publisher for what she saw as errors and distortions perpetrated by the book's ghostwriter. She was arrested twice for shoplifting, once in 1966 and once in 1991, but neither arrest resulted in a conviction.

Personal Life, Death and Legacy

Lamarr was married six times. She adopted a son, James, in 1939, during her second marriage to Gene Markey. She went on to have two biological children, Denise (b. 1945) and Anthony (b. 1947), with her third husband, actor John Loder, who also adopted James.

In 1953, Lamarr completed the naturalization process and became a U.S. citizen.

In her later years, Lamarr lived a reclusive life in Casselberry, a community just north of Orlando, Florida, where she died on January 19, 2000, at the age of 85.

Documentary and Pop Culture

In 2017, director Alexandra Dean shined a light on the Hollywood starlet/unlikely inventor with a new documentary, Bombshell: The Hedy Lamarr Story . Along with delving into her pioneering technological work, the documentary explores other examples in which Lamarr proved to be far more than just a pretty face, as well as her struggles with crippling drug addiction.

A dramatized version of Lamarr featured in a March 2018 episode of the TV series Timeless , which centered on her efforts to help the time-traveling team recover a stolen workprint of the 1941 classic Citizen Kane .

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Hedy Lamarr

- Birth Year: 1914

- Birth date: November 9, 1914

- Birth City: Vienna

- Birth Country: Austria

- Best Known For: Hedy Lamarr was an Austrian American actress during MGM's "Golden Age" who also left her mark on technology. She helped develop an early technique for spread spectrum communications.

- Astrological Sign: Scorpio

- Nacionalities

- Interesting Facts

- Hedy Lamarr was arrested twice for shoplifting, in 1966 and 1991, though neither arrest resulted in a conviction.

- Death Year: 2000

- Death date: January 19, 2000

- Death State: Florida

- Death City: Casselberry

- Death Country: United States

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Hedy Lamarr Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/actors/hedy-lamarr

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: April 19, 2021

- Original Published Date: April 2, 2014

Famous Actors

Donald Glover

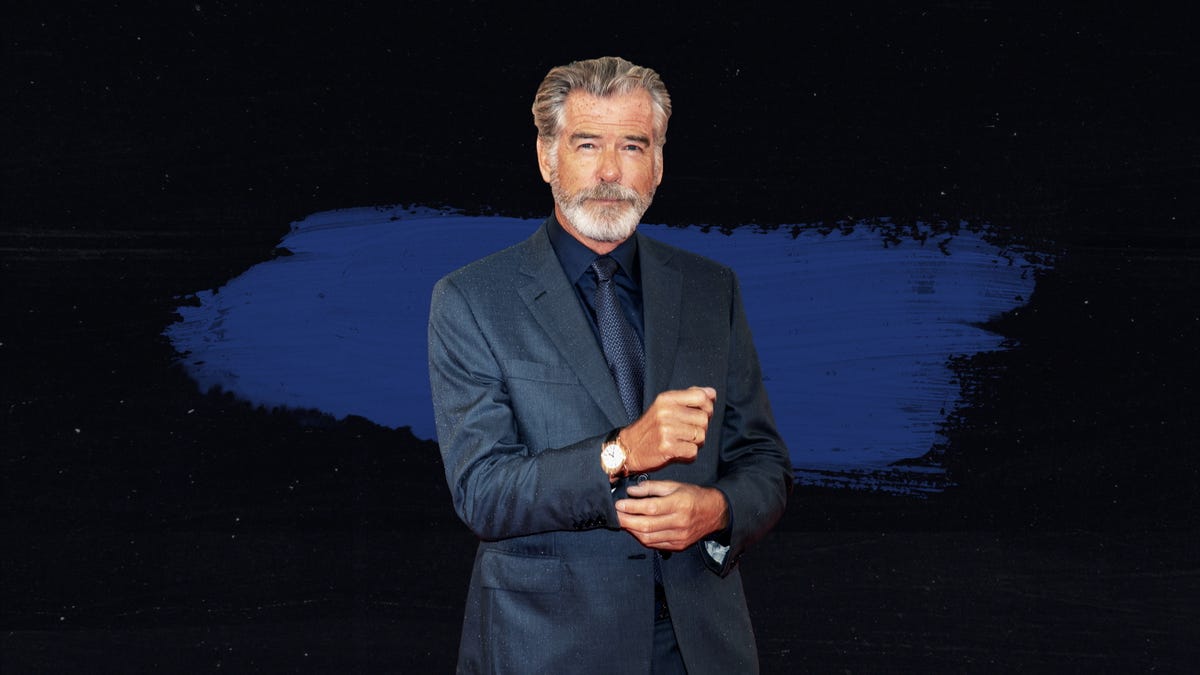

Ralph Fiennes

Get to Know ‘Terrifier 3’ Actor Lauren LaVera

You Definitely Forgot These Actors Were on ‘SNL’

Cynthia Erivo

Paul Mescal

Riley Keough

Meet ‘Monsters’ Star Nicholas Alexander Chavez

Daniel Day-Lewis

Maggie Smith

Get to Know ‘Monsters’ Breakout Star Cooper Koch

Hedy Lamarr

Hedy Lamarr was an Austrian-American actress and inventor who pioneered the technology that would one day form the basis for today’s WiFi, GPS, and Bluetooth communication systems. As a natural beauty seen widely on the big screen in films like Samson and Delilah and White Cargo , society has long ignored her inventive genius.

Lamarr was originally Hedwig Eva Kiesler, born in Vienna, Austria on November 9 th , 1914 into a well-to-do Jewish family. An only child, Lamarr received a great deal of attention from her father, a bank director and curious man, who inspired her to look at the world with open eyes. He would often take her for long walks where he would discuss the inner-workings of different machines, like the printing press or street cars. These conversations guided Lamarr’s thinking and at only 5 years of age, she could be found taking apart and reassembling her music box to understand how the machine operated. Meanwhile, Lamarr’s mother was a concert pianist and introduced her to the arts, placing her in both ballet and piano lessons from a young age.

Lamarr’s brilliant mind was ignored, and her beauty took center stage when she was discovered by director Max Reinhardt at age 16. She studied acting with Reinhardt in Berlin and was in her first small film role by 1930, in a German film called Geld auf der Stra βe (“Money on the Street”). However, it wasn’t until 1932 that Lamarr gained name recognition as an actress for her role in the controversial film, Ecstasy .

Austrian munitions dealer, Fritz Mandl, became one of Lamarr’s adoring fans when he saw her in the play Sissy . Lamarr and Mandl married in 1933 but it was short-lived. She once said, “I knew very soon that I could never be an actress while I was his wife … He was the absolute monarch in his marriage … I was like a doll. I was like a thing, some object of art which had to be guarded—and imprisoned—having no mind, no life of its own.” She was incredibly unhappy, as she was forced to play host and smile on demand amongst Mandl’s friends and scandalous business partners, some of whom were associated with the Nazi party. She escaped from Mandl’s grasp in 1937 by fleeing to London but took with her the knowledge gained from dinner-table conversation over wartime weaponry.

While in London, Lamarr’s luck took a turn when she was introduced to Louis B. Mayer, of the famed MGM Studios. With this meeting, she secured her ticket to Hollywood where she mystified American audiences with her grace, beauty, and accent. In Hollywood, Lamarr was introduced to a variety of quirky real-life characters, such as businessman and pilot Howard Hughes.

Lamarr dated Hughes but was most notably interested with his desire for innovation. Her scientific mind had been bottled-up by Hollywood but Hughes helped to fuel the innovator in Lamarr, giving her a small set of equipment to use in her trailer on set. While she had an inventing table set up in her house, the small set allowed Lamarr to work on inventions between takes. Hughes took her to his airplane factories, showed her how the planes were built, and introduced her to the scientists behind process. Lamarr was inspired to innovate as Hughes wanted to create faster planes that could be sold to the US military. She bought a book of fish and a book of birds and looked at the fastest of each kind. She combined the fins of the fastest fish and the wings of the fastest bird to sketch a new wing design for Hughes’ planes. Upon showing the design to Hughes, he said to Lamarr, “You’re a genius.”

Lamarr was indeed a genius as the gears in her inventive mind continued to turn. She once said, “Improving things comes naturally to me.” She went on to create an upgraded stoplight and a tablet that dissolved in water to make a soda similar to Coca-Cola. However, her most significant invention was engineered as the United States geared up to enter World War II.

In 1940 Lamarr met George Antheil at a dinner party. Antheil was another quirky yet clever force to be reckoned with. Known for his writing, film scores, and experimental music compositions, he shared the same inventive spirit as Lamarr. She and Antheil talked about a variety of topics but of their greatest concerns was the looming war. Antheil recalled, “Hedy said that she did not feel very comfortable, sitting there in Hollywood and making lots of money when things were in such a state.” After her marriage to Mandl, she had knowledge on munitions and various weaponry that would prove beneficial. And so, Lamarr and Antheil began to tinker with ideas to combat the axis powers.

The two came up with an extraordinary new communication system used with the intention of guiding torpedoes to their targets in war. The system involved the use of “frequency hopping” amongst radio waves, with both transmitter and receiver hopping to new frequencies together. Doing so prevented the interception of the radio waves, thereby allowing the torpedo to find its intended target. After its creation, Lamarr and Antheil sought a patent and military support for the invention. While awarded U.S. Patent No. 2,292,387 in August of 1942, the Navy decided against the implementation of the new system. The rejection led Lamarr to instead support the war efforts with her celebrity by selling war bonds. Happy in her adopted country, she became an American citizen in April 1953.

Meanwhile, Lamarr’s patent expired before she ever saw a penny from it. While she continued to accumulate credits in films until 1958, her inventive genius was yet to be recognized by the public. It wasn’t until Lamarr’s later years that she received any awards for her invention. The Electronic Frontier Foundation jointly awarded Lamarr and Antheil with their Pioneer Award in 1997. Lamarr also became the first woman to receive the Invention Convention’s Bulbie Gnass Spirit of Achievement Award. Although she died in 2000, Lamarr was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame for the development of her frequency hopping technology in 2014. Such achievement has led Lamarr to be dubbed “the mother of Wi-Fi” and other wireless communications like GPS and Bluetooth.

Bedi, Joyce. “A Movie Star, Some Player Pianos, and Torpedoes.” Smithsonian National Museum of American History: Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation, November 12, 2015.

Camhi, Leslie. “Hedy Lamarr’s Forgotten, Frustrated Career as a Wartime Inventor.” The New Yorker , December 3, 2017.

DeFore, John. “'Bombshell: The Hedy Lamarr Story': Film Review | Tribeca 2017.” The Hollywood Reporter , April 25, 2017.

“Hedy Lamarr: Biography.” IMDb.com.

“Hedy Lamarr Biography.” Biography.com. April 2, 2014.

“'Most Beautiful Woman' By Day, Inventor By Night.” All Things Considered , NPR, November 22, 2011.

“Women in Science: How Hedy Lamarr Pioneered Modern Wi-Fi Technology.” TEDxUCLWomen. July 30, 2017.

Y.F.. “The incredible inventiveness of Hedy Lamarr.” The Economist, November 23, 2017.

APA: Cheslak, C. (2018, August 30). Hedy Lamarr. Retrieved from https://www.womenshistory.org/students-and-educators/biographies/hedy-lamarr

MLA: Cheslak, Colleen. “Hedy Lamarr.” Hedy Lamarr , National Women's History Museum, 30 Aug. 2018, www.womenshistory.org/students-and-educators/biographies/hedy-lamarr.

Chicago:Cheslak, Colleen. "Hedy Lamarr." Hedy Lamarr. August 30, 2018. https://www.womenshistory.org/students-and-educators/biographies/hedy-lamarr.

Rhodes, Richard. Hedy's Folly: The Life and Breakthrough Inventions of Hedy Lamarr, the Most Beautiful Woman in the World . New York: Doubleday, 2011.

Bombshell: The Hedy Lamarr Story. Directed by Alexandra Dean. New York: Zeitgeist Films, November 24, 2017.

Related Biographies

Stacey Abrams

Abigail Smith Adams

Jane Addams

Toshiko Akiyoshi

Related background, agnes demille’s rodeo and images of women on the frontier, exploring maria tallchief: a dance journey through history, voices of change: analyzing speeches by lgbtq+ women, mary church terrell .

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

How Hollywood Star Hedy Lamarr Invented the Tech Behind WiFi

By: Dave Roos

Published: March 5, 2024

In the 1940s, few Hollywood actresses were more famous and more famously beautiful than Hedy Lamarr. Yet despite starring in dozens of films and gracing the cover of every Hollywood celebrity magazine, few people knew Hedy was also a gifted inventor. In fact, one of the technologies she co-invented laid a key foundation for future communication systems, including GPS, Bluetooth and WiFi.

“Hedy always felt that people didn't appreciate her for her intelligence—that her beauty got in the way,” says Richard Rhodes, a Pulitzer Prize-winning historian who wrote a biography about Hedy.

After working 12- or 15-hour days at MGM Studios, Hedy would often skip the Hollywood parties or carousing with one of her many suitors and instead sit down at her “inventing table.”

“Hedy had a drafting table and a whole wall full of engineering books. It was a serious hobby,” says Rhodes, author of Hedy's Folly: The Life and Breakthrough Inventions of Hedy Lamarr, the Most Beautiful Woman in the World .

While not a trained engineer or mathematician, Hedy Lamarr was an ingenious problem-solver. Most of her inventions were practical solutions to everyday problems, like a tissue box attachment for depositing used tissues or a glow-in-the-dark dog collar.

It was during World War II , that she developed “frequency hopping,” an invention that’s now recognized as a fundamental technology for secure communications. She didn’t receive credit for the innovation until very late in life.

Hedy Lamarr's Childhood in Austria

Hedy Lamarr was born Hedwig Eva Kiesler in Vienna, Austria in 1914. She was the only child of a wealthy secular Jewish family. From her father, a bank director, and her mother, a concert pianist, Hedy received a debutante’s education—ballet classes, piano lessons and equestrian training.

There were signs at a young age that Hedy had an engineer’s natural curiosity. On long walks through the bustling streets of Vienna, Hedy’s father would explain how the streetcars worked and how their electricity was generated at the power plant. At five years old, Hedy took apart a music box and reassembled it piece by piece.

“Hedy did not grow up with any technical education, but she did have this personal connection,” says Rhodes. “She loved her father dearly, so it’s easy to see how from that she might have developed an interest in the subject. And also it prepared her to be what she really was, a kind of amateur inventor.”

Hedy's Movie Debut as Teen

Even if Hedy had wanted to be a professional engineer or scientist, that career path wasn’t available to Viennese girls in the 1930s. Instead, teenage Hedy set her sights on the movie industry.

“At 16,” says Rhodes, “Hedy forged a note to her teachers in Vienna saying, ‘My daughter won’t be able to come to school today,’ so she could go down to the biggest movie studio in Europe and walk in the door and say, ‘Hi, I want to be a movie star.’”

Hedy started as a script girl, but quickly earned some walk-on parts. The Austrian director Max Reinhardt took Hedy to Berlin when she starred in a few forgettable films before landing a role at age 18 in a racy film called Ecstasy by the Czech director Gustav Machatý. The film was denounced by Pope Pious XI, banned from Germany and blocked by US Customs authorities for being “dangerously indecent.”

Reinhardt called Hedy “the most beautiful woman in Europe,” and even before Ecstasy , Hedy was turning heads in theater productions across Europe. It was during the Viennese run of a popular play called Sissy that Hedy caught the eye of a wealthy Austrian munitions baron named Fritz Mandl. Hedy and Mandl married in 1933, but the union was stifling from the start. Mandl forced his wife to accompany him as he struck deals with customers, including officials from Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, including Mussolini himself.

“She would sit at dinner bored out of her mind with discussions of bombs and torpedoes, and yet she was also absorbing it,” says Rhodes. “Of course, nobody asked her any questions. She was supposed to be beautiful and silent. But I think it was through that experience that she developed her considerable knowledge about how torpedo guidance worked.”

In 1937, Hedy fled her unhappy marriage (Mandl was deeply paranoid that Hedy was cheating on him) and also fled Austria, a country aligned with Adolf Hitler’s anti-Jewish policies.

A New Country and a New Name

Hedy landed in London, where Louis B. Mayer of MGM Studios was actively buying up the contracts of Jewish actors who could no longer work safely in Europe. Hedy met with Mayer, but refused his lowball offer of $125 a week for an exclusive MGM contract. In a savvy move, Hedy booked passage to the United States on the luxury liner SS Normandie , the same ship on which Mayer was traveling home.

“She made a point of being seen on deck looking beautiful and playing tennis with some of the handsome guys on board,” says Rhodes. “By the time they got to New York, Hedy had cut a much better deal with Mayer”—$500 a week—“with the proviso that she’d learn how to speak English in six months.”

Mayer had another demand—she had to change her name. Hedwig Kiesler was too German-sounding. Mayer’s wife was a fan of 1920s actress Barbara La Marr (who died tragically at 29 years old), so Mayer decided that his new MGM actor would now be known as Hedy Lamarr.

Actress by Day, Inventor by Night

It didn’t take long for Hedy to emerge as a bright new star in Hollywood. Her breakout role was alongside Charles Boyer (another European transplant) in Algiers (1938). From there, the MGM machine put Hedy to work cranking out multiple feature films a year throughout the 1940s.

“Any girl can be glamorous,” Hedy once quipped. “All you have to do is stand still and look stupid.”

As much as Hedy enjoyed her Hollywood stardom, her first love was still tinkering and problem-solving. She found a kindred spirit in Howard Hughes, the film producer and aeronautical engineer. When Hedy shared an idea for a dissolvable tablet that could turn a soldier’s canteen into a soft drink, Hughes lent her a few of his chemists.

But most of Hedy’s work was done at home at her engineering table where she’d sketch designs for creative solutions to practical problems. In addition to the tissue box attachment and the light-up dog collar, Hedy devised a special shower seat for the elderly that swiveled safely out of a bathtub.

“She was an inventor,” says Rhodes. “If you’ve ever been around real inventors, they’re often not people with a particularly deep education. They’re people who think about the world in a certain way. When they find something that doesn’t work right, instead of just swearing or whatever the rest of us do, they figure out how to fix it.”

Lamarr Takes on German U-Boats

In 1940, Hedy was distraught by the news coming out of Europe, where the Nazi war machine was steadily gaining territory and German U-boat submarines were wreaking havoc in the Atlantic. This was a far more difficult problem to fix, but Hedy was determined to do her part in the war effort.

The turning point came when Hedy met a man at a dinner party. George Antheil was an avante-garde music composer who lost his brother in the earliest days of the war. Antheil and Hedy were kindred spirits—two brilliant, if unconventional minds dead set on finding a way to defeat Hitler. But how?

That’s when Rhodes thinks Hedy leaned on the knowledge she picked up years earlier during those boring client dinners with her first husband in Vienna.

“She knew about torpedoes,” says Rhodes. “She knew there was a problem aiming torpedoes. If the British could take out German submarines with torpedoes launched from surface ships or airplanes, they might be able to prevent all of this slaughter that was going on.”

The answer was clearly some type of radio-controlled torpedo, but how would they stop the Germans from simply jamming the radio signal? Hedy and Antheil’s creative solution was inspired, Rhodes believes, by their mutual love of the piano.

Lamarr, Antheil Harness Music to Inspire Invention

During their late-night brainstorming sessions, Hedy and Antheil played a musical game. They’d sit down at the piano together, one person would start playing a popular song and the other would see how quickly they could recognize it and start playing along.

It was here, Rhodes thinks, that Hedy and Antheil first happened upon the idea of frequency hopping. If two musicians are playing the same music, they can hop around the keyboard together in perfect sync. However, if someone listening doesn’t know the song, they have no idea what keys will be pressed next. The “signal,” in other words, was hidden in the constantly changing frequencies.

How did this apply to radio-controlled torpedoes? The Germans could easily jam a single radio frequency, but not a constantly changing “symphony” of frequencies.

In his experimental musical compositions, Antheil had written songs for multiple synchronized player pianos. The pianos played in sync because they were fed the same piano rolls—a type of primitive, cut-out paper program—that controlled which keys were played and when. What if he and Hedy could invent a similar method for synchronizing communications between a torpedo and its controller on a nearby ship?

“All you need are two synchronized clocks that start a tape going at the same moment on the ship and inside the torpedo,” says Rhodes. “The signal between the ship and the torpedo would be continuous, even though it was traveling across a new frequency every split second. The effect for anyone trying to jam the signal is that they wouldn’t know where it was from one moment to the next, because it would ‘hopping’ all over the radio.”

It was Hedy who named their clever system “frequency hopping.”

Navy Rejects Invention

Hedy and Antheil developed their idea with the help of a wartime agency called the National Inventors’ Council , tasked with applying civilian inventions to the war effort. The Council connected Hedy and Antheil with a physicist from the California Institute of Technology who figured out the complex electronics to make it all work.

When their frequency hopping patent was finalized in 1942, Antheil pitched the idea to the U.S. Navy, which was less than receptive.

“What do you want to do, put a player piano in a torpedo? Get out of here!” is how Rhodes describes the Navy’s knee-jerk rejection. It was never given a chance.

Hedy and Antheil’s patent was locked in a safe and labeled “top secret” for the remainder of the war. The two entertainers went back to their day jobs, thinking that was the end of their inventing days. Little did they know that their patent would have a second life.

Frequency Hopping Tech Takes Off

In the 1950s, the electrical manufacturer Sylvania employed frequency hopping to build a secure system for communicating with submarines. And in the early 1960s, the technology was deployed on U.S. warships to prevent Soviet signal jamming during the Cuban Missile Crisis .

Antheil died in 1959, but Hedy lived on, unaware that her ingenious idea was about to take off in a big way.

When car phones first became popular in the 1970s, carriers used frequency hopping to enable hundreds of callers to share a limited spectrum of radio frequencies. The same technology was rolled out for the earliest cell phone networks.

By the 1990s, frequency hopping was so ubiquitous that it became the technology standard required by the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) for secure radio communications. That’s why Bluetooth, WiFi and other essential technologies are based, at their core, on an idea dreamed up by Hedy Lamarr and George Antheil.

“It’s a really deep and fundamental idea,” says Rhodes. “It has broad applications all over the place.”

Over time, Hedy’s Hollywood star fizzled and she retired to Florida, where she continued to tinker with new inventions, including a more “driver-friendly” type of traffic light. It wasn’t until Hedy was in her 80s that a group of engineers realized that the “Hedwig Kiesler Mackay” listed on the frequency hopping patent was none other than the Hollywood legend, Hedy Lamarr.

“Hedy didn’t want money, but she did want recognition,” says Rhodes, “and it really angered her that nobody gave her credit for this important invention. In the 1990s, she finally got an award for her contribution. And Hedy being Hedy, what did she say? ‘Well, it’s about time.’”

HISTORY Vault: Women's History

Stream acclaimed women's history documentaries in HISTORY Vault.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Hedy Lamarr (1914-2000)

Additional crew.

IMDbPro Starmeter Top 5,000 128

- 4 wins & 1 nomination

- Jenny Hager

- Princess Veronica

- Dolores Sweets Ramirez

- Vanessa Windsor

- Consuela Bowers

- Joan of Arc

- (scenes deleted)

- Imperatrice Giuseppina

- Genoveffa di Brabante

- Hedy Windsor

- Elana di Troia

- Empress Josephine ...

- Lily Dalbray

- Marianne Lorress

- Lisa Roselle

- Dr. J.O. Loring

- Madeleine Damien

- executive producer

- stand-in: Nancy Kelly (uncredited)

Personal details

- Official Site

- Hedwig Kiesler

- 5′ 7″ (1.70 m)

- November 9 , 1914

- Vienna, Austria-Hungary [now Austria]

- January 19 , 2000

- Casselberry, Florida, USA (natural causes)

- Spouses Lewis William Boies Jr. March 4, 1963 - June 21, 1965 (divorced)

- Children James Lamarr Markey

- Parents Emil Kiesler

- Other works (7/13/42) Radio: Appeared in a "Lux Radio Theater" production of "H.M. Pulham, Esq."

- 3 Biographical Movies

- 9 Print Biographies

- 4 Portrayals

- 17 Articles

- 28 Pictorials

- 18 Magazine Cover Photos

Did you know

- Trivia Inspired by an early Philco wireless radio remote and player piano rolls, she worked with composer George Antheil (who created a symphony played by eight synchronized player pianos) she invented a frequency-hopping system for remotely controlling torpedoes during World War II. (The frequency hopping concept appeared as early as 1903 in a U.S. Patent by Nikola Tesla). The invention was examined superficially and filed away. At the time, Allied torpedoes, as well as those of the Axis powers, were unguided. Input for depth, speed, and direction were made moments before launch but once leaving the submarine the torpedo received no further input. In 1959 it was developed for controlling drones that would later be used in Viet Nam. Frequency hopping radio became a Navy standard by 1960. Due to the expiration of the patent and Lamarr's unawareness of time limits for filing claims, she was never compensated. Her invention is used today for WiFi, Bluetooth, and even top secret military defense satellites. While the current estimate of the value of the invention is approximately $30 billion, during her final years she was getting by on SAG and social security checks totaling only $300 a month.

- Quotes I must quit marrying men who feel inferior to me. Somewhere, there must be a man who could be my husband and not feel inferior. I need a superior inferior man.

- Trademarks Natural brunette hair

- Hollywood's Loveliest Legendary Lady

- Queen of Glamour

- Salaries A Lady Without Passport ( 1950 ) $90,000

- When did Hedy Lamarr die?

- How did Hedy Lamarr die?

- How old was Hedy Lamarr when she died?

Related news

Contribute to this page.

- Learn more about contributing

More to explore

Recently viewed.

Site Navigation

Hedy Lamarr: Golden Age Film Star—and Important Inventor

Actor Hedy Lamarr (1914–2000) had a fascinating life, including her scandalous debut in the Czech film Ecstasy, discovery (and renaming) by Louis B. Mayer, persona as the most glamorous woman of Hollywood's Golden Age, and relative obscurity in her later years.

But far beyond the Hollywood image, Lamarr was an inventor.

She was born Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler in Vienna, Austria. Her father was the director of a bank and her Hungarian mother was a concert pianist.

During a small dinner party in 1940, Lamarr met a kindred inventive spirit in George Antheil. The Trenton, New Jersey, native was known for his writing, his film scores—especially his avant-garde music compositions—but he was also an inventor.

Lamarr wanted to aid the Allied forces during World War II. She explored potential military applications for radio technology. She theorized that varying radio frequencies at irregular intervals would prevent interception or jamming of transmissions, thereby creating an innovative communication system.

Lamarr shared her concept for using “frequency hopping” with the U.S. Navy and codeveloped a patent with Antheil 1941. Today, her innovation helped make possible a wide range of wireless communications technologies, including Wi-Fi, GPS, and Bluetooth.

This image is in the collection of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

Read more about Lamarr’s story and inventions in this blog post by Joyce Bedi for the museum’s Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation .

An image of Lamarr’s patent can be viewed online at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum.

Collections

- Open Access

A History of Voting by Mail

IMAGES

VIDEO