Free Will and Argument Against Its Existence Essay

If one was to ask a random person whether they have free will, the answer would likely be affirmative, for a variety of reasons. It is both challenging and incomprehensible for most human beings to accept that their life may be guided by something other than the free will of decision-making. However, the concept of determinism, although not directly meant to challenge free will, ultimately suggests incompatibility. Determinism is a theory which states that the course of the future is determined by a combination of past events and the laws of nature, creating a unique outcome. It argues that the events that are secured in the past, combined with laws of nature that drive the real world, results in a possible reality where the very same events and natural laws would apply, and therefore, shape the future. Causal determinism is the primary argument against free will presented in this paper using the following premises:

- P1. The universe is deterministic with past events and laws of nature bring subsequent change and a unique future;

- P2. Humans have no influence or choice about the laws of nature or events in the past;

- P3. Events of past or nature are determined by physical forces since human actions are events, in reality, then they are determined by physical forces;

- P4. If humans do not cause or originate actions, then these events are not controlled by us, thus lacking the ability of self-determination;

- P5. The no-choice principle – a lack of influence on the inputs, resulting in a lack of control over the output or predetermined future;

Determinism is incompatible with freedom of will.

P1 is the basic premise of determinism. P2 examines the human ability to influence said premise. P3 creates the sequence which affects human decisions. P4 explores how the concept of free will plays into determinism. P5 presents a theory and closing argument. The conclusion is the final logical assumption based on the premises.

There are several schools of thought regarding determinism and free will. There are the compatibilism perspectives that suggest that both free will and determinism are real and can co-exist or are mutually compatible in reality. While compatibilists believe at least partially in some effect of a metaphysical combination of past events and natural laws, the freedom of choice ultimately depends on the situation, sometimes humans are forced by circumstance while in other times, humans are free agents. Compatibilists argue that determinism does not suggest a lack of free will because it does not entail that humans ever act on their desires unencumbered

The incompatibilism perspective views free will and determinism as conflicting, with two schools emerging of libertarianism which suggests free will exists in the indeterministic world, and hard determinism that presents a world with no free will. Hard determinism will be explored here, through a concept known as the consequence argument or “no choice principle.” It follows the basic premise of how one can have a choice about something that is an outcome of something that one has no influence on. Therefore, since no human being has a choice about past events or laws of nature, the logical conclusion is that there is no choice about current decisions, supporting determinism.

According to determinism, the state of the universe results in the decision. With laws of nature stating that if a specific state of the universe would lead to certain outcomes. No one has a choice about that sequence of events or the state of the universe or laws of nature, and it is consequential that no one has any choice about the decision. Such conditional proof eliminates any aspect of free will. For example, John is placed in a situation where he has to either lie or tell the truth. This decision is based on a pulse from the brain which converts to behavioral action. For the pulse in the brain to go one way or another, one has to consider the laws of nature as well as the state of John’s brain and related aspects. For John to decide on which way the pulse must go, he had to have done something beforehand to influence it. Since he did not do this, the direction is undetermined and there is no freedom. If John was really free, he must have had an influence on the event leading up to this position, but instead, it was determined by a sequence of prior events and the laws of nature. Every action and thought coming from John are consistent with the prior event both occurring and not occurring. If there is no genuine choice, and the decision is random, it is not an exemplification of free will – fully supporting hard determinism.

The primary philosophical interest and concern in the free will v. determinism argument are actually motivated by the external factor of moral responsibility. If the no-consequence argument is accepted and determinism stands true as the force precludes free will, the same applies to moral responsibility since it is generally accepted that freedom is a necessary condition for one to take responsibility for the course of action. However, the concepts are mutually exclusive as moral responsibility is a scope of ethics rather than compatibilism and incompatibilism. It is also a matter of perception on moral responsibility, whereas proponents of free will argue that only self-determination and full control of one’s actions can present an appropriate platform for the evaluation of morality.

At the same time, supporters of hard determinism demonstrate an argument on their own. The compatibility of moral responsibility with determinism had to be proven via that the ability to do otherwise (alternative action) was also compatible. Eventually, the principle of alternate possibilities was introduced, which suggested that whether one was a supporter of compatibilism or incompatibilism, the ability to choose is not necessary for moral responsibility. It was demonstrated through a two-step thought experiment. In the context of free will, there is a person named John who is faced with a morally challenging decision, and he chooses an immoral alternative, therefore burdening the responsibility. There is an omnipotent being, a threat, or penalty which would punish John if he did not act accordingly. Any sort of coercion mechanism can be implied here, but it would only intervene if John makes an alternate choice. By coincidence, John acts exactly as the coercive mechanism wants, making the decision.

The question arises, whether John is morally responsible for the action even though he was coerced. It is implied that the threat is so significant that John has no other choice, thus the lack of “alternate possibilities.” However, since John acted according to the will of a higher being, there was no intervention and nobody ultimately forced him to make that choice. This is a metaphor for determinism, which suggests that it does not matter whether an individual has free will, because choices are not genuine, always guided by some sort of coercion, and one is unable to choose otherwise. Therefore, moral responsibility is largely irrelevant to the outcome, but rather applies during the actual sequence of events.

As criticism of determinism, it can be argued that if one has knowledge about past events and laws of nature, possessing some intelligence, one can predict the future, thus acting in free will to change it. The no-choice principle becomes challenged as, in this scenario, it would no longer meet the premise. Even if determinism stands true, it is entirely possible for the future to be unpredictable since there is an inherently weak link between a determined future and a predictable future. Humans generally lack the necessary intellectual capacity or the full understanding of past and natural events to make accurate assumptions about the future and cannot be used as an argument that determinism does not exist.

In conclusion, determinism presents a strong argument against the existence of a free will. In comparison to more abstract philosophies such as Laplace’s demon, causal determinism is more grounded in logic. The primary issue with determinism is that it is currently empirically impossible to prove that the universe is deterministic, thus challenging the premises. Furthermore, there are a number of perspectives on whether determinism and free will are compatible and able to co-exist.

The author of this paper does not align with a particular school of thought but most closely relates to compatibilism in the context of Ayer’s Paradox. Ultimately, it does not matter whether determinism is true, or events are probabilistic, as neither demonstrates free will and in both realities, moral responsibility is denied. If events could not have been avoided based on the deterministic argument, then there is no free will or moral responsibility, and the same outcome emerges even if events are random, the combination of factors and natural forces still lead to certain decisions which a human cannot interpret. Free will does not exist in the context that most people assume, as choices are bound to either causal laws or statistical law, which one is unable to escape, and this does not meet the requirements for freedom of action.

- Master Zhuang's Philosophical Theory of Freedom

- Boredom and Freedom: Different Views and Links

- Are We Free to Act and Think as We Like?

- Free Will and Determinism Analysis

- Against Free Will: Determinism and Prediction

- Determinism Argument and Objection to It

- The Existence of Freedom

- Van Inwagen’s Philosophical Argument on Free Will

- Mill's Power over Body vs. Foucault's Freedom

- Rousseau’s vs. Confucius’ Freedom Concept

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, September 11). Free Will and Argument Against Its Existence. https://ivypanda.com/essays/free-will-and-argument-against-its-existence/

"Free Will and Argument Against Its Existence." IvyPanda , 11 Sept. 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/free-will-and-argument-against-its-existence/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'Free Will and Argument Against Its Existence'. 11 September.

IvyPanda . 2021. "Free Will and Argument Against Its Existence." September 11, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/free-will-and-argument-against-its-existence/.

1. IvyPanda . "Free Will and Argument Against Its Existence." September 11, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/free-will-and-argument-against-its-existence/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Free Will and Argument Against Its Existence." September 11, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/free-will-and-argument-against-its-existence/.

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

IvyPanda uses cookies and similar technologies to enhance your experience, enabling functionalities such as:

- Basic site functions

- Ensuring secure, safe transactions

- Secure account login

- Remembering account, browser, and regional preferences

- Remembering privacy and security settings

- Analyzing site traffic and usage

- Personalized search, content, and recommendations

- Displaying relevant, targeted ads on and off IvyPanda

Please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy for detailed information.

Certain technologies we use are essential for critical functions such as security and site integrity, account authentication, security and privacy preferences, internal site usage and maintenance data, and ensuring the site operates correctly for browsing and transactions.

Cookies and similar technologies are used to enhance your experience by:

- Remembering general and regional preferences

- Personalizing content, search, recommendations, and offers

Some functions, such as personalized recommendations, account preferences, or localization, may not work correctly without these technologies. For more details, please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy .

To enable personalized advertising (such as interest-based ads), we may share your data with our marketing and advertising partners using cookies and other technologies. These partners may have their own information collected about you. Turning off the personalized advertising setting won't stop you from seeing IvyPanda ads, but it may make the ads you see less relevant or more repetitive.

Personalized advertising may be considered a "sale" or "sharing" of the information under California and other state privacy laws, and you may have the right to opt out. Turning off personalized advertising allows you to exercise your right to opt out. Learn more in IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy .

Free Will Essay example

Free Will I want to argue that there is indeed free will. In order to defend the position that free will means that human beings can cause some of what they do on their own; in other words, what they do is not explainable solely by references to factors that have influenced them. My thesis then, is that human beings are able to cause their own actions and they are therefore responsible for what they do. In a basic sense we are all original actors capable of making moves in the world. We are initiators of our own behavior. The first matter to be noted is that this view is in no way in contradiction to science. Free will is a natural phenomenon, something that emerged in nature with the emergence of human beings, with their …show more content…

Dogs, lizards, fish, cats, frogs, etc.; have no free will and therefore it appears arbitrary to impute it to human beings. Why should we do things that the rest of nature lacks? It would be an impossible aberration. The answer here, is that there is enough variety in nature—some things swim, some fly, some just lie there, some breathe, some grow, while others do not; so there is plenty of evidence of plurality of types and kinds of things in nature. Discovering that something has free will could be yet another addition to all the varieties of nature. I am going to give four agruments on why, in my opinion free will exists. The first argument has to deal with determinism . If we are fully determined in what we think, believe and do, then of course the belief that determinism is true is also a result of this determinism. But the same is true for the belief that determinism is false. There is nothing you can do about whatever you believe—you had to believe it. There is no way to take an independent stance and consider the arguments unprejudiced because all various forces making us assimilate the evidence in the world just the way we do. One either turns out to be a determinist or not and in neither case can we appraise the issue because we are pre-determined to have a view on that matter one way or another. We will never be able to resolve this debate, since there is no way of truly knowing. In

Essay on Determinism and Free will

There are those who think that our behavior is a result of free choice, but there are also others who believe we are servants of cosmic destiny, and that behavior is nothing but a reflex of heredity and environment. The position of determinism is that every event is the necessary outcome of a cause or set of causes, and everything is a consequence of external forces, and such forces produce all that happens. Therefore, according to this statement, man is not free.

D Holbach Free Will Essay

The arguments presented by D’Holbach and Hobart contain many of the same premises and opinions regarding the human mind, but nonetheless differ in their conclusion on whether we have free will. In this paper, I will explain how their individual interpretations of the meaning of free will resulted in having contrary arguments.

Free Will And The Brain Capacity

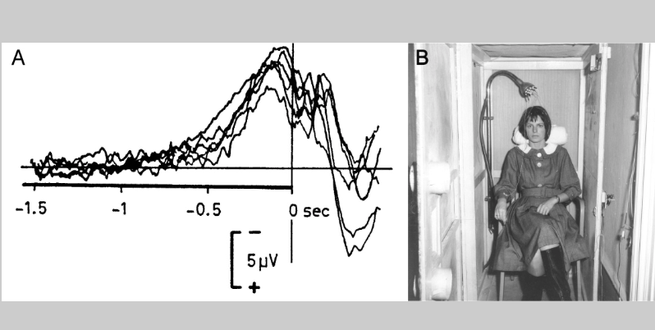

What is free will? As stated in the Merriam-Webster dictionary, free will is “the ability to choose how to act; the ability to make choices that are not controlled by fate or God.” Are we free? Do we have the brain capacity to exercise free will? This is a widely debated topic by scientists and philosophers alike. The answer is almost always no. There is no way that we are completely free. But why do they think this? Most scientists believe that everything is predetermined. Scientists Hans Helmut Kornhuber and Lüder Deecke discovered a phenomenon called “readiness potential.” They discovered that the brain entrs into a certain state prior to conscious awareness. Basically, your brain knows what it is going to do before your conscious knows. They believed that there is no room in our brain, in our society, to be completely free and to exercise free will. It’s just impossible. Even Charles Darwin, the father of the theory of evolution, said “everything in nature is the result of fixed laws.”

The True Nature Of Moral Responsibility

It also depends on how we explain free will; free will in this case is how one acts out on their own will. Our genetics can determine how we can act. When our

Cause And Effect Essay On Fate And Freewill

Your geography and you beliefs determined greatly who you are as a person but no one had a choice on that during their formative years. So there are so many factors and causes that affect freewill that’s not under the individual’s control. Let’s acknowledge that. In the context of life being a canvas you can visualize your life as a specific and unique individual pathway on the canvas of life with with different choices(options) available as one moves through time. At each moment in time, different choices are available to you within said predetermined path. The pathway is already predetermined because all time exist at all time all the time, but within each moment you’re are presented with certain set of choices (different set of choices are available at different point in time). These choices range from good to evil as far as their impacts are concerned. So this is why it makes sense to say true freewill doesn’t exist but we can make choices within the predetermined path we find ourselves in. If you think about it from a believer point of view, it’s basically God created everyone differently (predetermined path), with different gifts (drives) manifested through choices available to us at each moment in time. Evil and good are natural forces in this world which

Determinism Is Self-Refuting Research Paper

Yes,if we don't have free will, why are we here? What is the point of life if we cannot choose our own paths? Yet from a purely scientific perspective, how is it possible that anything can occur without

Daniel Dennett Free Will Analysis

My perspective of free will takes after that of the logician Daniel Dennett. Dennett is in some cases excessively sharp for his own particular great. You feel as though he's attempting to pull a quick one on you, as when he contends, in his 1991 book, Consciousness Explained, that awareness has been, very much, clarified, which I question even he truly accepts. Yet, in his 2003 book, Freedom Evolves, Dennett lays out a sensible, rational perspective of free will. He notes, initially, that free will is "not what convention proclaims it to be: a Godlike energy to absolved oneself from the causal fabric of the physical world." Free will is just our capacity to see, think about, and follow up on decisions; truth be told, decision, or even freedom,

Causal Determinsim

- 5 Works Cited

Causal determinism is the concept that preceding causes give rise to everything which exists such that reality could be nothing but what it is. Science depends on this idea as it aims to find generalisations about the conjunction of certain causes and effects and thus hold some power of prediction about their future co-occurrence. However, in human interaction people assume each other to be responsible for their acts and not merely at the whim of causal laws. So the question which troubles philosophers is whether causation dictates entirely the course of human action or whether we as agents possess some free will. I will argue that free will is an inescapable illusion of the mind, something which never did nor ever could exist under

Why Do People Have Free Will Just An Illusion?

Free will means that humans are self determined, and not subject to forces outside of their control. What free will tries to account for is that people are in control of many of their choices, thus they are in control of their own destiny. Some

Do We Have Free Will

There are many great philosophical ideas and questions that are known and of course unknown. One of the questions that really enticed my interest was the question of whether or not we have free will. I myself was once a believer of people having free will and doing what I want was my choice and my choice alone. However, after careful consideration and lectures I have been reversed in how I believe in free will. Is there any free will though? Many people would say yes there is and of course there are some who believe that free will is a fallacy and not to be believed. Whether or not there is free will is yet to be determined but what we have to go on and by is from philosophers and every person who has their two cents to fill in. In

Why Do We Have Free Will?

Kant and Hegel felt that our free will gives us the ability to reason and should think through our mental abilities. Our choices that we make of the world obtains our desired result. These choices that we make are in our genetics that we have and the experiences make us who we are. Daniel Dennett is a compatibilist he believes that the only free will that we have is the free will that we think we have. If people feel like they have free will then they will have free will. Quantum Mechanics feel that our free will is that the human consciousness has super powers and that the universe hold the potential for the human conscious to exist. Some other quantum mechanics feel that protons and electrons take on random values and this makes up our free will. Buddhist feel that in order to have feel will that we must have freedom from physical necessity. We must not have constraints of the natural world. We need to have a duel view of reality for us to operate from the physical world when we are immersed into free will. In order for this to happen the pineal gland in our brain would have to have a connection to the physical world and the non-physical world. For free will to take effect in this it should only be one-way. Our will should be free and should not be acted upon. Frankenstein Argument says that we must create ourselves. We are only responsible for the person that we have created when we created ourselves. (Reeve, 2013)

Why Do Free Will Exist

Free will is something that everyone thinks they have no one has ever thought that that maybe all the choices they make were already predetermined billions of years ago, or that our brain makes choices before we are consciously aware of those choices, or that the laws of physics are deterministic and that everything we do follows these laws. Even though these claims and many more could lead someone to believe we don’t have free will there are some faults in these claims that could make it possible for there to be a chance of free will.

Do Humans Have Free Will

Free will: the ability as humans to dictate our conscious decision-making. Does it exist or is it just an illusion, our every thought and action being decided when the universe was created? This question has puzzled philosophers for ages. There is no doubt that this issue makes those who ponder about the meaning of life even more unsure. If our actions are predetermined, what does this mean for personal and criminal responsibility? For respect, religion, morals, ethics, and the law? Our world has evolved based on the assumption that free will exists, so what are we to do if everything we have experienced can boil down to some simple (or maybe not so simple) chemistry and genetics? What happens if everything we believe in turns out to be just an idea?

Is Free Will An Illusion?

Free will determines my life because I have the power to chose what I want to do with my life. I can choose to get bad grades and not have a successful career. Disobeying my parents and getting in trouble is part of having free will. Choosing the right decisions when faced with a tough situation is a part of my free will. Or vice versa if I were to work hard on the assignments that where given to me I would be rewarded handsomely. I believe that everything we do in our lives has been decided by our own actions, no external force has played a role in our lives we are the outcome of our own lives.

Philosophy Of Free Will

Facts state that we are biological creatures made up of molecules that adhere to the laws of physics. If science is as reputable as we make it out to be, then the regularity of those laws determines how every single molecule in the known universe acts. As a population, humans are merely constructs of one vital organ, the brain- a supercomputer capable of naming itself. And this goes without saying that the human brain (the organ designated as doing the choosing in our everyday decisions) is made up of these exact same molecules. Everything humans think, do, or say, must come down to the behavior of these molecules according to the laws they follows. The concept of free will is based upon an illusion that people can choose their actions; however that is not the case. Due to the fact that the brain is composed of chemicals, neurons, and molecules that are subject to the law of physics, an individual’s actions become the result of the chemical and molecular changes within the brain. These changes are based on the biological makeup of the individual and the environmental factors the individual

Related Topics

- Human brain

- Metaphysics

Why the Classical Argument Against Free Will Is a Failure

In the last several years, a number of prominent scientists have claimed that we have good scientific reason to believe that there’s no such thing as free will — that free will is an illusion. If this were true, it would be less than splendid. And it would be surprising, too, because it really seems like we have free will. It seems that what we do from moment to moment is determined by conscious decisions that we freely make.

We need to look very closely at the arguments that these scientists are putting forward to determine whether they really give us good reason to abandon our belief in free will. But before we do that, it would behoove us to have a look at a much older argument against free will — an argument that’s been around for centuries.

The older argument against free will is based on the assumption that determinism is true. Determinism is the view that every physical event is completely caused by prior events together with the laws of nature. Or, to put the point differently, it’s the view that every event has a cause that makes it happen in the one and only way that it could have happened.

If determinism is true, then as soon as the Big Bang took place 13 billion years ago, the entire history of the universe was already settled. Every event that’s ever occurred was already predetermined before it occurred. And this includes human decisions. If determinism is true, then everything you’ve ever done — every choice you’ve ever made — was already predetermined before our solar system even existed. And if this is true, then it has obvious implications for free will.

Suppose that you’re in an ice cream parlor, waiting in line, trying to decide whether to order chocolate or vanilla ice cream. And suppose that when you get to the front of the line, you decide to order chocolate. Was this choice a product of your free will? Well, if determinism is true, then your choice was completely caused by prior events. The immediate causes of the decision were neural events that occurred in your brain just prior to your choice. But, of course, if determinism is true, then those neural events that caused your decision had physical causes as well; they were caused by even earlier events — events that occurred just before they did. And so on, stretching back into the past. We can follow this back to when you were a baby, to the very first events of your life. In fact, we can keep going back before that, because if determinism is true, then those first events were also caused by prior events. We can keep going back to events that occurred before you were even conceived, to events involving your mother and father and a bottle of Chianti.

If determinism is true, then as soon as the Big Bang took place 13 billion years ago, the entire history of the universe was already settled.

So if determinism is true, then it was already settled before you were born that you were going to order chocolate ice cream when you got to the front of the line. And, of course, the same can be said about all of our decisions, and it seems to follow from this that human beings do not have free will.

Let’s call this the classical argument against free will . It proceeds by assuming that determinism is true and arguing from there that we don’t have free will.

There’s a big problem with the classical argument against free will. It just assumes that determinism is true. The idea behind the argument seems to be that determinism is just a commonsense truism. But it’s actually not a commonsense truism. One of the main lessons of 20th-century physics is that we can’t know by common sense, or by intuition, that determinism is true. Determinism is a controversial hypothesis about the workings of the physical world. We could only know that it’s true by doing some high-level physics. Moreover — and this is another lesson of 20th-century physics — as of right now, we don’t have any good evidence for determinism. In other words, our best physical theories don’t answer the question of whether determinism is true.

During the reign of classical physics (or Newtonian physics), it was widely believed that determinism was true. But in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, physicists started to discover some problems with Newton’s theory, and it was eventually replaced with a new theory — quantum mechanics . (Actually, it was replaced by two new theories, namely, quantum mechanics and relativity theory. But relativity theory isn’t relevant to the topic of free will.) Quantum mechanics has several strange and interesting features, but the one that’s relevant to free will is that this new theory contains laws that are probabilistic rather than deterministic. We can understand what this means very easily. Roughly speaking, deterministic laws of nature look like this:

If you have a physical system in state S, and if you perform experiment E on that system, then you will get outcome O.

But quantum physics contains probabilistic laws that look like this:

If you have a physical system in state S, and if you perform experiment E on that system, then there are two different possible outcomes, namely, O1 and O2; moreover, there’s a 50 percent chance that you’ll get outcome O1 and a 50 percent chance that you’ll get outcome O2.

It’s important to notice what follows from this. Suppose that we take a physical system, put it into state S, and perform experiment E on it. Now suppose that when we perform this experiment, we get outcome O1. Finally, suppose we ask the following question: “Why did we get outcome O1 instead of O2?” The important point to notice is that quantum mechanics doesn’t answer this question . It doesn’t give us any explanation at all for why we got outcome O1 instead of O2. In other words, as far as quantum mechanics is concerned, it could be that nothing caused us to get result O1 ; it could be that this just happened .

Now, Einstein famously thought that this couldn’t be the whole story. You’ve probably heard that he once said that “God doesn’t play dice with the universe.” What he meant when he said this was that the fundamental laws of nature can’t be probabilistic. The fundamental laws, Einstein thought, have to tell us what will happen next, not what will probably happen, or what might happen. So Einstein thought that there had to be a hidden layer of reality , below the quantum level, and that if we could find this hidden layer, we could get rid of the probabilistic laws of quantum mechanics and replace them with deterministic laws, laws that tell us what will happen next, not just what will probably happen next. And, of course, if we could do this — if we could find this hidden layer of reality and these deterministic laws of nature — then we would be able to explain why we got outcome O1 instead of O2.

But a lot of other physicists — most notably, Werner Heisenberg and Niels Bohr — disagreed with Einstein. They thought that the quantum layer of reality was the bottom layer. And they thought that the fundamental laws of nature — or at any rate, some of these laws — were probabilistic laws. But if this is right, then it means that at least some physical events aren’t deterministically caused by prior events. It means that some physical events just happen . For instance, if Heisenberg and Bohr are right, then nothing caused us to get outcome O1 instead of O2; there was no reason why this happened; it just did .

The debate between determinists like Einstein and indeterminists like Heisenberg and Bohr has never been settled.

The debate between Einstein on the one hand and Heisenberg and Bohr on the other is crucially important to our discussion. Einstein is a determinist. If he’s right, then every physical event is predetermined — or in other words, completely caused by prior events. But if Heisenberg and Bohr are right, then determinism is false . On their view, not every event is predetermined by the past and the laws of nature; some things just happen , for no reason at all. In other words, if Heisenberg and Bohr are right, then indeterminism is true.

And here’s the really important point for us. The debate between determinists like Einstein and indeterminists like Heisenberg and Bohr has never been settled. We don’t have any good evidence for either view. Quantum mechanics is still our best theory of the subatomic world, but we just don’t know whether there’s another layer of reality, beneath the quantum layer. And so we don’t know whether all physical events are completely caused by prior events. In other words, we don’t know whether determinism or indeterminism is true. Future physicists might be able to settle this question, but as of right now, we don’t know the answer.

But now notice that if we don’t know whether determinism is true or false, then this completely undermines the classical argument against free will. That argument just assumed that determinism is true. But we now know that there is no good reason to believe this. The question of whether determinism is true is an open question for physicists. So the classical argument against free will is a failure — it doesn’t give us any good reason to conclude that we don’t have free will.

Despite the failure of the classical argument, the enemies of free will are undeterred. They still think there’s a powerful argument to be made against free will. In fact, they think there are two such arguments. Both of these arguments can be thought of as attempts to fix the classical argument, but they do this in completely different ways.

The first new-and-improved argument against free will — which is a scientific argument — starts with the observation that it doesn’t matter whether the full-blown hypothesis of determinism is true because it doesn’t matter whether all events are predetermined by prior events. All that matters is whether our decisions are predetermined by prior events. And the central claim of the first new-and-improved argument against free will is that we have good evidence (from studies performed by psychologists and neuroscientists) for thinking that, in fact, our decisions are predetermined by prior events.

The second new-and-improved argument against free will — which is a philosophical argument, not a scientific argument — relies on the claim that it doesn’t matter whether determinism is true because in determinism is just as incompatible with free will as determinism is. The argument for this is based on the claim that if our decisions aren’t determined, then they aren’t caused by anything, which means that they occur randomly . And the central claim of the second new-and-improved argument against free will is that if our decisions occur randomly, then they just happen to us , and so they’re not the products of our free will.

My own view is that neither of these new-and-improved arguments succeeds in showing that we don’t have free will. But it takes a lot of work to undermine these two arguments. In order to undermine the scientific argument, we need to explain why the relevant psychological and neuroscientific studies don’t in fact show that we don’t have free will. And in order to undermine the philosophical argument, we need to explain how a decision could be the product of someone’s free will — how the outcome of the decision could be under the given person’s control — even if the decision wasn’t caused by anything.

So, yes, this would all take a lot of work. Maybe I should write a book about it.

Mark Balaguer is Professor in the Department of Philosophy at California State University, Los Angeles. He is the author of several books, including “ Free Will ,” from which this article is adapted.

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

The term “free will” has emerged over the past two millennia as the canonical designator for a significant kind of control over one’s actions. Questions concerning the nature and existence of this kind of control (e.g., does it require and do we have the freedom to do otherwise or the power of self-determination?), and what its true significance is (is it necessary for moral responsibility or human dignity?) have been taken up in every period of Western philosophy and by many of the most important philosophical figures, such as Plato, Aristotle, Augustine, Aquinas, Descartes, and Kant. (We cannot undertake here a review of related discussions in other philosophical traditions. For a start, the reader may consult Marchal and Wenzel 2017 and Chakrabarti 2017 for overviews of thought on free will, broadly construed, in Chinese and Indian philosophical traditions, respectively.) In this way, it should be clear that disputes about free will ineluctably involve disputes about metaphysics and ethics. In ferreting out the kind of control at stake in free will, we are forced to consider questions about (among others) causation, laws of nature, time, substance, ontological reduction vs emergence, the relationship of causal and reasons-based explanations, the nature of motivation and more generally of human persons. In assessing the significance of free will, we are forced to consider questions about (among others) rightness and wrongness, good and evil, virtue and vice, blame and praise, reward and punishment, and desert. The topic of free will also gives rise to purely empirical questions that are beginning to be explored in the human sciences: do we have it, and to what degree?

Here is an overview of what follows. In Section 1 , we acquaint the reader with some central historical contributions to our understanding of free will. (As nearly every major and minor figure had something to say about it, we cannot begin to cover them all.) As with contributions to many other foundational topics, these ideas are not of ‘merely historical interest’: present-day philosophers continue to find themselves drawn back to certain thinkers as they freshly engage their contemporaries. In Section 2 , we map the complex architecture of the contemporary discussion of the nature of free will by dividing it into five subtopics: its relation to moral responsibility; the proper analysis of the freedom to do otherwise; a powerful, recent argument that the freedom to do otherwise (at least in one important sense) is not necessary for moral responsibility; ‘compatibilist’ accounts of sourcehood or self-determination; and ‘incompatibilist’ or ‘libertarian’ accounts of source and self-determination. In Section 3 , we consider arguments from experience, a priori reflection, and various scientific findings and theories for and against the thesis that human beings have free will, along with the related question of whether it is reasonable to believe that we have it. Finally, in Section 4 , we survey the long-debated questions involving free will that arise in classical theistic metaphysics.

1.1 Ancient and Medieval Period

1.2 modern period and twentieth century, 2.1 free will and moral responsibility, 2.2 the freedom to do otherwise, 2.3 freedom to do otherwise vs. sourcehood accounts, 2.4 compatibilist accounts of sourcehood, 2.5 libertarian accounts of sourcehood, 3.1 arguments against the reality of free will, 3.2 arguments for the reality of free will, 4.1 free will and god’s power, knowledge, and goodness, 4.2 god’s freedom, other internet resources, related entries, 1. major historical contributions.

One finds scholarly debate on the ‘origin’ of the notion of free will in Western philosophy. (See, e.g., Dihle (1982) and, in response Frede (2011), with Dihle finding it in St. Augustine (354–430 CE) and Frede in the Stoic Epictetus (c. 55–c. 135 CE).) But this debate presupposes a fairly particular and highly conceptualized concept of free will, with Dihle’s later ‘origin’ reflecting his having a yet more particular concept in view than Frede. If, instead, we look more generally for philosophical reflection on choice-directed control over one’s own actions, then we find significant discussion in Plato and Aristotle (cf. Irwin 1992). Indeed, on this matter, as with so many other major philosophical issues, Plato and Aristotle give importantly different emphases that inform much subsequent thought.

In Book IV of The Republic , Plato posits rational, spirited, and appetitive aspects to the human soul. The wise person strives for inner ‘justice’, a condition in which each part of the soul plays its proper role—reason as the guide, the spirited nature as the ally of reason, exhorting oneself to do what reason deems proper, and the passions as subjugated to the determinations of reason. In the absence of justice, the individual is enslaved to the passions. Hence, freedom for Plato is a kind of self-mastery, attained by developing the virtues of wisdom, courage, and temperance, resulting in one’s liberation from the tyranny of base desires and acquisition of a more accurate understanding and resolute pursuit of the Good (Hecht 2014).

While Aristotle shares with Plato a concern for cultivating virtues, he gives greater theoretical attention to the role of choice in initiating individual actions which, over time, result in habits, for good or ill. In Book III of the Nicomachean Ethics , Aristotle says that, unlike nonrational agents, we have the power to do or not to do, and much of what we do is voluntary, such that its origin is ‘in us’ and we are ‘aware of the particular circumstances of the action’. Furthermore, mature humans make choices after deliberating about different available means to our ends, drawing on rational principles of action. Choose consistently well (poorly), and a virtuous (vicious) character will form over time, and it is in our power to be either virtuous or vicious.

A question that Aristotle seems to recognize, while not satisfactorily answering, is whether the choice an individual makes on any given occasion is wholly determined by his internal state—perception of his circumstances and his relevant beliefs, desires, and general character dispositions (wherever on the continuum between virtue and vice he may be)—and external circumstances. He says that “the man is the father of his actions as of children”—that is, a person’s character shapes how she acts. One might worry that this seems to entail that the person could not have done otherwise—at the moment of choice, she has no control over what her present character is—and so she is not responsible for choosing as she does. Aristotle responds by contending that her present character is partly a result of previous choices she made. While this claim is plausible enough, it seems to ‘pass the buck’, since ‘the man is the father’ of those earlier choices and actions, too.

We note just a few contributions of the subsequent centuries of the Hellenistic era. (See Bobzien 1998.) This period was dominated by debates between Epicureans, Stoics, and the Academic Skeptics, and as it concerned freedom of the will, the debate centered on the place of determinism or of fate in governing human actions and lives. The Stoics and the Epicureans believed that all ordinary things, human souls included, are corporeal and governed by natural laws or principles. Stoics believed that all human choice and behavior was causally determined, but held that this was compatible with our actions being ‘up to us’. Chrysippus ably defended this position by contending that your actions are ‘up to you’ when they come about ‘through you’—when the determining factors of your action are not external circumstances compelling you to act as you do but are instead your own choices grounded in your perception of the options before you. Hence, for moral responsibility, the issue is not whether one’s choices are determined (they are) but in what manner they are determined. Epicurus and his followers had a more mechanistic conception of bodily action than the Stoics. They held that all things (human soul included) are constituted by atoms, whose law-governed behavior fixes the behavior of everything made of such atoms. But they rejected determinism by supposing that atoms, though law-governed, are susceptible to slight ‘swerves’ or departures from the usual paths. Epicurus has often been understood as seeking to ground the freedom of human willings in such indeterministic swerves, but this is a matter of controversy. If this understanding of his aim is correct, how he thought that this scheme might work in detail is not known. (What little we know about his views in this matter stem chiefly from the account given in his follower Lucretius’s six-book poem, On the Nature of Things . See Bobzien 2000 for discussion.)

A final notable figure of this period was Alexander of Aphrodisias , the most important Peripatetic commentator on Aristotle. In his On Fate , Alexander sharply criticizes the positions of the Stoics. He goes on to resolve the ambiguity in Aristotle on the question of the determining nature of character on individual choices by maintaining that, given all such shaping factors, it remains open to the person when she acts freely to do or not to do what she in fact does. Many scholars see Alexander as the first unambiguously ‘libertarian’ theorist of the will (for more information about such theories see section 2 below).

Augustine (354–430) is the central bridge between the ancient and medieval eras of philosophy. His mature thinking about the will was influenced by his early encounter with late classical Neoplatonist thought, which is then transformed by the theological views he embraces in his adult Christian conversion, famously recounted in his Confessions . In that work and in the earlier On the Free Choice of the Will , Augustine struggles to draw together into a coherent whole the doctrines that creaturely misuse of freedom, not God, is the source of evil in the world and that the human will has been corrupted through the ‘fall’ from grace of the earliest human beings, necessitating a salvation that is attained entirely through the actions of God, even as it requires, constitutively, an individual’s willed response of faith. The details of Augustine’s positive account remain a matter of controversy. He clearly affirms that the will is by its nature a self-determining power—no powers external to it determine its choice—and that this feature is the basis of its freedom. But he does not explicitly rule out the will’s being internally determined by psychological factors, as Chrysippus held, and Augustine had theological reasons that might favor (as well as others that would oppose) the thesis that all things are determined in some manner by God. Scholars divide on whether Augustine was a libertarian or instead a kind of compatibilist with respect to metaphysical freedom. (Macdonald 1999 and Stump 2006 argue the former, Baker 2003 and Couenhoven 2007 the latter.) It is clear, however, that Augustine thought that we are powerfully shaped by wrongly-ordered desires that can make it impossible for us to wholeheartedly will ends contrary to those desires, for a sustained period of time. This condition entails an absence of something more valuable, ‘true freedom’, in which our wills are aligned with the Good, a freedom that can be attained only by a transformative operation of divine grace. This latter, psychological conception of freedom of will clearly echoes Plato’s notion of the soul’s (possible) inner justice.

Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) attempted to synthesize major strands of Aristotle’s systematic philosophy with Christian theology, and so Aquinas begins his complex discussion of human action and choice by agreeing with Aristotle that creatures such as ourselves who are endowed with both intellect and will are hardwired to will certain general ends ordered to the most general goal of goodness. Will is rational desire: we cannot move towards that which does not appear to us at the time to be good. Freedom enters the picture when we consider various means to these ends and move ourselves to activity in pursuit of certain of them. Our will is free in that it is not fixed by nature on any particular means, and they generally do not appear to us either as unqualifiedly good or as uniquely satisfying the end we wish to fulfill. Furthermore, what appears to us to be good can vary widely—even, over time, intra-personally. So much is consistent with saying that in a given total circumstance (including one’s present beliefs and desires), one is necessitated to will as one does. For this reason, some commentators have taken Aquinas to be a kind of compatibilist concerning freedom and causal or theological determinism. In his most extended defense of the thesis that the will is not ‘compelled’ ( DM 6), Aquinas notes three ways that the will might reject an option it sees as attractive: (i) it finds another option more attractive, (ii) it comes to think of some circumstance rendering an alternative more favorable “by some chance circumstance, external or internal”, and (iii) the person is momentarily disposed to find an alternative attractive by virtue of a non-innate state that is subject to the will (e.g., being angry vs being at peace). The first consideration is clearly consistent with compatibilism. The second at best points to a kind of contingency that is not grounded in the activity of the will itself. And one wanting to read Aquinas as a libertarian might worry that his third consideration just passes the buck: even if we do sometimes have an ability to directly modify perception-coloring states such as moods, Aquinas’s account of will as rational desire seems to indicate that we will do so only if it seems to us on balance to be good to do so. Those who read Aquinas as a libertarian point to the following further remark in this text: “Will itself can interfere with the process [of some cause’s moving the will] either by refusing to consider what attracts it to will or by considering its opposite: namely, that there is a bad side to what is being proposed…” (Reply to 15; see also DV 24.2). For discussion, see MacDonald (1998), Stump (2003, ch. 9) and especially Hoffman & Michon (2017), which offers the most comprehensive analysis of relevant texts to date.

John Duns Scotus (1265/66–1308) was the stoutest defender in the medieval era of a strongly libertarian conception of the will, maintaining on introspective grounds that will by its very nature is such that “nothing other than the will is the total cause” of its activity ( QAM ). Indeed, he held the unusual view that not only up to but at the very instant that one is willing X , it is possible for one to will Y or at least not to will X . (He articulates this view through the puzzling claim that a single instant of time comprises two ‘instants of nature’, at the first but not the second of which alternative possibilities are preserved.) In opposition to Aquinas and other medieval Aristotelians, Scotus maintained that a precondition of our freedom is that there are two fundamentally distinct ways things can seem good to us: as practically advantageous to us or as according with justice. Contrary to some popular accounts, however, Scotus allowed that the scope of available alternatives for a person will be more or less constricted. He grants that we are not capable of willing something in which we see no good whatsoever, nor of positively repudiating something which appears to us as unqualifiedly good. However, in accordance with his uncompromising position that nothing can be the total cause of the will other than itself, he held that where something does appear to us as unqualifiedly good (perfectly suited both to our advantage and justice)—viz., in the ‘beatific vision’ of God in the afterlife—we still can refrain from willing it. For discussion, see John Duns Scotus, §5.2 .

The problem of free will was an important topic in the modern period, with all the major figures wading into it (Descartes 1641 [1988], 1644 [1988]; Hobbes 1654 [1999], 1656 [1999]; Spinoza 1677 [1992]; Malebranche 1684 [1993]; Leibniz 1686 [1991]; Locke 1690 [1975]; Hume 1740 [1978], 1748 [1975]; Edwards 1754 [1957]; Kant 1781 [1998], 1785 [1998], 1788 [2015]; Reid 1788 [1969]). After less sustained attention in the 19th Century (most notable were Schopenhauer 1841 [1999] and Nietzsche 1886 [1966]), it was widely discussed again among early twentieth century philosophers (Moore 1912; Hobart 1934; Schlick 1939; Nowell-Smith 1948, 1954; Campbell 1951; Ayer 1954; Smart 1961). The centrality of the problem of free will to the various projects of early modern philosophers can be traced to two widely, though not universally, shared assumptions. The first is that without belief in free will, there would be little reason for us to act morally. More carefully, it was widely assumed that belief in an afterlife in which a just God rewards and punishes us according to our right or wrong use of free will was key to motivating us to be moral (Russell 2008, chs. 16–17). Life before death affords us many examples in which vice is better rewarded than virtue and so without knowledge of a final judgment in the afterlife, we would have little reason to pursue virtue and justice when they depart from self-interest. And without free will there can be no final judgement.

The second widely shared assumption is that free will seems difficult to reconcile with what we know about the world. While this assumption is shared by the majority of early modern philosophers, what specifically it is about the world that seems to conflict with freedom differs from philosopher to philosopher. For some, the worry is primarily theological. How can we make sense of contingency and freedom in a world determined by a God who must choose the best possible world to create? For some, the worry was primarily metaphysical. The principle of sufficient reason—roughly, the idea that every event must have a reason or cause—was a cornerstone of Leibniz’s and Spinoza’s metaphysics. How does contingency and freedom fit into such a world? For some, the worry was primarily scientific (Descartes). Given that a proper understanding of the physical world is one in which all physical objects are governed by deterministic laws of nature, how does contingency and freedom fit into such a world? Of course, for some, all three worries were in play in their work (this is true especially of Leibniz).

Despite many disagreements about how best to solve these worries, there were three claims that were widely, although not universally, agreed upon. The first was that free will has two aspects: the freedom to do otherwise and the power of self-determination. The second is that an adequate account of free will must entail that free agents are morally responsible agents and/or fit subjects for punishment. Ideas about moral responsibility were often a yard stick by which analyses of free will were measured, with critics objecting to an analysis of free will by arguing that agents who satisfied the analysis would not, intuitively, be morally responsible for their actions. The third is that compatibilism—the thesis that free will is compatible with determinism—is true. (Spinoza, Reid, and Kant are the clear exceptions to this, though some also see Descartes as an incompatibilist [Ragland 2006].)

Since a detailed discussion of these philosophers’ accounts of free will would take us too far afield, we want instead to focus on isolating a two-step strategy for defending compatibilism that emerges in the early modern period and continued to exert considerable force into the early twentieth century (and perhaps is still at work today). Advocates of this two-step strategy have come to be known as “classical compatibilists”. The first step was to argue that the contrary of freedom is not determinism but external constraint on doing what one wants to do. For example, Hobbes contends that liberty is “the absence of all the impediments to action that are not contained in the nature and intrinsical quality of the agent” (Hobbes 1654 [1999], 38; cf. Hume 1748 [1975] VIII.1; Edwards 1754 [1957]; Ayer 1954). This idea led many compatibilists, especially the more empiricist-inclined, to develop desire- or preference-based analyses of both the freedom to do otherwise and self-determination. An agent has the freedom to do otherwise than \(\phi\) just in case if she preferred or willed to do otherwise, she would have done otherwise (Hobbes 1654 [1999], 16; Locke 1690 [1975]) II.xx.8; Hume 1748 [1975] VIII.1; Moore 1912; Ayer 1954). The freedom to do otherwise does not require that you are able to act contrary to your strongest motivation but simply that your action be dependent on your strongest motivation in the sense that had you desired something else more strongly, then you would have pursued that alternative end. (We will discuss this analysis in more detail below in section 2.2.) Similarly, an agent self-determines her \(\phi\)-ing just in case \(\phi\) is caused by her strongest desires or preferences at the time of action (Hobbes 1654 [1999]; Locke 1690 [1975]; Edwards 1754 [1957]). (We will discuss this analysis in more detail below in section 2.4.) Given these analyses, determinism seems innocuous to freedom.

The second step was to argue that any attempt to analyze free will in a way that putatively captures a deeper or more robust sense of freedom leads to intractable conundrums. The most important examples of this attempt to capture a deeper sense of freedom in the modern period are Immanuel Kant (1781 [1998], 1785 [1998], 1788 [2015]) and Thomas Reid (1788 [1969]) and in the early twentieth century C. A. Campbell (1951). These philosophers argued that the above compatibilist analyses of the freedom to do otherwise and self-determination are, at best, insufficient for free will, and, at worst, incompatible with it. With respect to the classical compatibilist analysis of the freedom to do otherwise, these critics argued that the freedom to do otherwise requires not just that an agent could have acted differently if he had willed differently, but also that he could have willed differently. Free will requires more than free action. With respect to classical compatibilists’ analysis of self-determination, they argued that self-determination requires that the agent—rather than his desires, preferences, or any other mental state—cause his free choices and actions. Reid explains:

I consider the determination of the will as an effect. This effect must have a cause which had the power to produce it; and the cause must be either the person himself, whose will it is, or some other being…. If the person was the cause of that determination of his own will, he was free in that action, and it is justly imputed to him, whether it be good or bad. But, if another being was the cause of this determination, either producing it immediately, or by means and instruments under his direction, then the determination is the act and deed of that being, and is solely imputed to him. (1788 [1969] IV.i, 265)

Classical compatibilists argued that both claims are incoherent. While it is intelligible to ask whether a man willed to do what he did, it is incoherent to ask whether a man willed to will what he did:

For to ask whether a man is at liberty to will either motion or rest, speaking or silence, which he pleases, is to ask whether a man can will what he wills , or be pleased with what he is pleased with? A question which, I think, needs no answer; and they who make a question of it must suppose one will to determine the acts of another, and another to determine that, and so on in infinitum . (Locke 1690 [1975] II.xx.25; cf. Hobbes 1656 [1999], 72)

In response to libertarians’ claim that self-determination requires that the agent, rather than his motives, cause his actions, it was objected that this removes the agent from the natural causal order, which is clearly unintelligible for human animals (Hobbes 1654 [1999], 38). It is important to recognize that an implication of the second step of the strategy is that free will is not only compatible with determinism but actually requires determinism (cf. Hume 1748 [1975] VIII). This was a widely shared assumption among compatibilists up through the mid-twentieth century.

Spinoza’s Ethics (1677 [1992]) is an important departure from the above dialectic. He endorses a strong form of necessitarianism in which everything is categorically necessary as opposed to the conditional necessity embraced by most compatibilists, and he contends that there is no room in such a world for divine or creaturely free will. Thus, Spinoza is a free will skeptic. Interestingly, Spinoza is also keen to deny that the nonexistence of free will has the dire implications often assumed. As noted above, many in the modern period saw belief in free will and an afterlife in which God rewards the just and punishes the wicked as necessary to motivate us to act morally. According to Spinoza, so far from this being necessary to motivate us to be moral, it actually distorts our pursuit of morality. True moral living, Spinoza thinks, sees virtue as its own reward (Part V, Prop. 42). Moreover, while free will is a chimera, humans are still capable of freedom or self-determination. Such self-determination, which admits of degrees on Spinoza’s view, arises when our emotions are determined by true ideas about the nature of reality. The emotional lives of the free persons are ones in which “we desire nothing but that which must be, nor, in an absolute sense, can we find contentment in anything but truth. And so in so far as we rightly understand these matters, the endeavor of the better part of us is in harmony with the order of the whole of Nature” (Part IV, Appendix). Spinoza is an important forerunner to the many free will skeptics in the twentieth century, a position that continues to attract strong support (see Strawson 1986; Double 1992; Smilansky 2000; Pereboom 2001, 2014; Levy 2011; Waller 2011; Caruso 2012; Vilhauer 2012. For further discussion see the entry skepticism about moral responsibility ).

It is worth observing that in many of these disputes about the nature of free will there is an underlying dispute about the nature of moral responsibility. This is seen clearly in Hobbes (1654 [1999]) and early twentieth century philosophers’ defenses of compatibilism. Underlying the belief that free will is incompatible with determinism is the thought that no one would be morally responsible for any actions in a deterministic world in the sense that no one would deserve blame or punishment. Hobbes responded to this charge in part by endorsing broadly consequentialist justifications of blame and punishment: we are justified in blaming or punishing because these practices deter future harmful actions and/or contribute to reforming the offender (1654 [1999], 24–25; cf. Schlick 1939; Nowell-Smith 1948; Smart 1961). While many, perhaps even most, compatibilists have come to reject this consequentialist approach to moral responsibility in the wake of P. F. Strawson’s 1962 landmark essay ‘Freedom and Resentment’ (though see Vargas (2013) and McGeer (2014) for contemporary defenses of compatibilism that appeal to forward-looking considerations) there is still a general lesson to be learned: disputes about free will are often a function of underlying disputes about the nature and value of moral responsibility.

2. The Nature of Free Will

As should be clear from this short discussion of the history of the idea of free will, free will has traditionally been conceived of as a kind of power to control one’s choices and actions. When an agent exercises free will over her choices and actions, her choices and actions are up to her . But up to her in what sense? As should be clear from our historical survey, two common (and compatible) answers are: (i) up to her in the sense that she is able to choose otherwise, or at minimum that she is able not to choose or act as she does, and (ii) up to her in the sense that she is the source of her action. However, there is widespread controversy both over whether each of these conditions is required for free will and if so, how to understand the kind or sense of freedom to do otherwise or sourcehood that is required. While some seek to resolve these controversies in part by careful articulation of our experiences of deliberation, choice, and action (Nozick 1981, ch. 4; van Inwagen 1983, ch. 1), many seek to resolve these controversies by appealing to the nature of moral responsibility. The idea is that the kind of control or sense of up-to-meness involved in free will is the kind of control or sense of up-to-meness relevant to moral responsibility (Double 1992, 12; Ekstrom 2000, 7–8; Smilansky 2000, 16; Widerker and McKenna 2003, 2; Vargas 2007, 128; Nelkin 2011, 151–52; Levy 2011, 1; Pereboom 2014, 1–2). Indeed, some go so far as to define ‘free will’ as ‘the strongest control condition—whatever that turns out to be—necessary for moral responsibility’ (Wolf 1990, 3–4; Fischer 1994, 3; Mele 2006, 17). Given this connection, we can determine whether the freedom to do otherwise and the power of self-determination are constitutive of free will and, if so, in what sense, by considering what it takes to be a morally responsible agent. On these latter characterizations of free will, understanding free will is inextricably linked to, and perhaps even derivative from, understanding moral responsibility. And even those who demur from this claim regarding conceptual priority typically see a close link between these two ideas. Consequently, to appreciate the current debates surrounding the nature of free will, we need to say something about the nature of moral responsibility.

It is now widely accepted that there are different species of moral responsibility. It is common (though not uncontroversial) to distinguish moral responsibility as answerability from moral responsibility as attributability from moral responsibility as accountability (Watson 1996; Fischer and Tognazzini 2011; Shoemaker 2011. See Smith (2012) for a critique of this taxonomy). These different species of moral responsibility differ along three dimensions: (i) the kind of responses licensed toward the responsible agent, (ii) the nature of the licensing relation, and (iii) the necessary and sufficient conditions for licensing the relevant kind of responses toward the agent. For example, some argue that when an agent is morally responsible in the attributability sense, certain judgments about the agent—such as judgments concerning the virtues and vices of the agent—are fitting , and that the fittingness of such judgments does not depend on whether the agent in question possessed the freedom to do otherwise (cf. Watson 1996).

While keeping this controversy about the nature of moral responsibility firmly in mind (see the entry on moral responsibility for a more detailed discussion of these issues), we think it is fair to say that the most commonly assumed understanding of moral responsibility in the historical and contemporary discussion of the problem of free will is moral responsibility as accountability in something like the following sense:

An agent \(S\) is morally accountable for performing an action \(\phi\) \(=_{df.}\) \(S\) deserves praise if \(\phi\) goes beyond what can be reasonably expected of \(S\) and \(S\) deserves blame if \(\phi\) is morally wrong.

The central notions in this definition are praise , blame , and desert . The majority of contemporary philosophers have followed Strawson (1962) in contending that praising and blaming an agent consist in experiencing (or at least being disposed to experience (cf. Wallace 1994, 70–71)) reactive attitudes or emotions directed toward the agent, such as gratitude, approbation, and pride in the case of praise, and resentment, indignation, and guilt in the case of blame. (See Sher (2006) and Scanlon (2008) for important dissents from this trend. See the entry on blame for a more detailed discussion.) These emotions, in turn, dispose us to act in a variety of ways. For example, blame disposes us to respond with some kind of hostility toward the blameworthy agent, such as verbal rebuke or partial withdrawal of good will. But while these kinds of dispositions are essential to our blaming someone, their manifestation is not: it is possible to blame someone with very little change in attitudes or actions toward the agent. Blaming someone might be immediately followed by forgiveness as an end of the matter.

By ‘desert’, we have in mind what Derk Pereboom has called basic desert :

The desert at issue here is basic in the sense that the agent would deserve to be blamed or praised just because she has performed the action, given an understanding of its moral status, and not, for example, merely by virtue of consequentialist or contractualist considerations. (2014, 2)

As we understand desert, if an agent deserves blame, then we have a strong pro tanto reason to blame him simply in virtue of his being accountable for doing wrong. Importantly, these reasons can be outweighed by other considerations. While an agent may deserve blame, it might, all things considered, be best to forgive him unconditionally instead.

When an agent is morally responsible for doing something wrong, he is blame worthy : he deserves hard treatment marked by resentment and indignation and the actions these emotions dispose us toward, such as censure, rebuke, and ostracism. However, it would seem unfair to treat agents in these ways unless their actions were up to them . Thus, we arrive at the core connection between free will and moral responsibility: agents deserve praise or blame only if their actions are up to them—only if they have free will. Consequently, we can assess analyses of free will by their implications for judgments of moral responsibility. We note that some might reject the claim that free will is necessary for moral responsibility (e.g., Frankfurt 1971; Stump 1988), but even for these theorists an adequate analysis of free will must specify a sufficient condition for the kind of control at play in moral responsibility.

In what follows, we focus our attention on the two most commonly cited features of free will: the freedom to do otherwise and sourcehood. While some seem to think that free will consists exclusively in either the freedom to do otherwise (van Inwagen 2008) or in sourcehood (Zagzebski 2000), many philosophers hold that free will involves both conditions—though philosophers often emphasize one condition over the other depending on their dialectical situation or argumentative purposes (cf. Watson 1987). In what follows, we will describe the most common characterizations of these two conditions.

For most newcomers to the problem of free will, it will seem obvious that an action is up to an agent only if she had the freedom to do otherwise. But what does this freedom come to? The freedom to do otherwise is clearly a modal property of agents, but it is controversial just what species of modality is at stake. It must be more than mere possibility : to have the freedom to do otherwise consists in more than the mere possibility of something else’s happening. A more plausible and widely endorsed understanding claims the relevant modality is ability or power (Locke 1690 [1975], II.xx; Reid 1788 [1969], II.i–ii; D. Locke 1973; Clarke 2009; Vihvelin 2013). But abilities themselves seem to come in different varieties (Lewis 1976; Horgan 1979; van Inwagen 1983, ch. 1; Mele 2003; Clarke 2009; Vihvelin 2013, ch. 1; Franklin 2015; Cyr and Swenson 2019; Hofmann 2022; Whittle 2022), so a claim that an agent has ‘the ability to do otherwise’ is potentially ambiguous or indeterminate; in philosophical discussion, the sense of ability appealed to needs to be spelled out. A satisfactory account of the freedom to do otherwise owes us both an account of the kind of ability in terms of which the freedom to do otherwise is analyzed, and an argument for why this kind of ability (as opposed to some other species) is the one constitutive of the freedom to do otherwise. As we will see, philosophers sometimes leave this second debt unpaid.

The contemporary literature takes its cue from classical compatibilism’s recognized failure to deliver a satisfactory analysis of the freedom to do otherwise. As we saw above, classical compatibilists (Hobbes 1654 [1999], 1656 [1999]; Locke 1690 [1975]; Hume 1740 [1978], 1748 [1975]; Edwards 1754 [1957]; Moore 1912; Schlick 1939; Ayer 1954) sought to analyze the freedom to do otherwise in terms of a simple conditional analysis of ability:

Simple Conditional Analysis: An agent \(S\) has the ability to do otherwise if and only if, were \(S\) to choose to do otherwise, then \(S\) would do otherwise.

Part of the attraction of this analysis is that it obviously reconciles the freedom to do otherwise with determinism. While the truth of determinism entails that one’s action is inevitable given the past and laws of nature, there is nothing about determinism that implies that if one had chosen otherwise, then one would not do otherwise.

There are two problems with the Simple Conditional Analysis . The first is that it is, at best, an analysis of free action, not free will (cf. Reid 1788 [1969]; Chisholm 1966; 1976, ch. 2; Lehrer 1968, 1976). It only tells us when an agent has the ability to do otherwise, not when an agent has the ability to choose to do otherwise. One might be tempted to think that there is an easy fix along the following lines:

Simple Conditional Analysis*: An agent \(S\) has the ability to choose otherwise if and only if, were \(S\) to desire or prefer to choose otherwise, then \(S\) would choose otherwise.

The problem is that we often fail to choose to do things we want to choose, even when it appears that we had the ability to choose otherwise (one might think the same problem attends the original analysis). Suppose that, in deciding how to spend my evening, I have a desire to choose to read and a desire to choose to watch a movie. Suppose that I choose to read. By all appearances, I had the ability to choose to watch a movie. And yet, according to the Simple Conditional Analysis* , I lack this freedom, since the conditional ‘if I were to desire to choose to watch a movie, then I would choose to watch a movie’ is false. I do desire to choose to watch a movie and yet I do not choose to watch a movie. It is unclear how to remedy this problem. On the one hand, we might refine the antecedent by replacing ‘desire’ with ‘strongest desire’ (cf. Hobbes 1654 [1999], 1656 [1999]; Edwards 1754 [1957]). The problem is that this assumes, implausibly, that we always choose what we most strongly desire (for criticisms of this view see Reid 1788 [1969]; Campbell 1951; Wallace 1999; Holton 2009). On the other hand, we might refine the consequent by replacing ‘would choose to do otherwise’ with either ‘would probably choose to do otherwise’ or ‘might choose to do otherwise’. But each of these proposals is also problematic. If ‘probably’ means ‘more likely than not’, then this revised conditional still seems too strong: it seems possible to have the ability to choose otherwise even when one’s so choosing is unlikely. If we opt for ‘might’, then the relevant sense of modality needs to be spelled out.

Even if there are fixes to these problems, there is a yet deeper problem with these analyses. There are some agents who clearly lack the freedom to do otherwise and yet satisfy the conditional at the heart of these analyses. That is, although these agents lack the freedom to do otherwise, it is, for example, true of them that if they chose otherwise, they would do otherwise. Picking up on an argument developed by Keith Lehrer (1968; cf. Campbell 1951; Broad 1952; Chisholm 1966), consider an agoraphobic, Luke, who, when faced with the prospect of entering an open space, is subject not merely to an irresistible desire to refrain from intentionally going outside, but an irresistible desire to refrain from even choosing to go outside. Given Luke’s psychology, there is no possible world in which he suffers from his agoraphobia and chooses to go outside. It may well nevertheless be true that if Luke chose to go outside, then he would have gone outside. After all, any possible world in which he chooses to go outside will be a world in which he no longer suffers (to the same degree) from his agoraphobia, and thus we have no reason to doubt that in those worlds he would go outside as a result of his choosing to go outside. The same kind of counterexample applies with equal force to the conditional ‘if \(S\) desired to choose otherwise, then \(S\) would choose otherwise’.