- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Why Are You So Anxious During Test Taking?

Sweaty palms, upset stomach, and a racing heartbeat...

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Amy Morin, LCSW, is a psychotherapist and international bestselling author. Her books, including "13 Things Mentally Strong People Don't Do," have been translated into more than 40 languages. Her TEDx talk, "The Secret of Becoming Mentally Strong," is one of the most viewed talks of all time.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/VW-MIND-Amy-2b338105f1ee493f94d7e333e410fa76.jpg)

- Identifying

Test anxiety is a psychological condition in which people experience extreme distress and anxiety in testing situations. While many people experience some degree of stress and anxiety before and during exams, test anxiety can actually impair learning and hurt test performance. Test anxiety is a type of performance anxiety. In situations where the pressure is on and a good performance counts, people can become so anxious that they are actually unable to do their best.

Many people experience stress or anxiety before an exam. In fact, a little nervousness can actually help you perform your best. However, when this distress becomes so excessive that it actually interferes with performance on an exam, it is known as test anxiety.

Identifying Test Anxiety

While people have the skills and knowledge to do very well in these situations, their excessive anxiety impairs their performance. The severity of test anxiety can vary considerably from one person to another. Some people might feel like they have "butterflies" in their stomachs, while others might find it difficult to concentrate on the exam. This can also manifest in the following ways:

- A businessman freezes up and forgets the information he was going to present to his co-workers and manager during a work presentation.

- A high school basketball player becomes very anxious before a big game. During the game, she is so overwhelmed by this stress that she starts missing even easy shots.

- A violin student becomes extremely nervous before a recital. During the performance, she messes up on several key passages and flubs her solo.

A little bit of nervousness can actually be helpful, making you feel mentally alert and ready to tackle the challenges presented in an exam. The Yerkes-Dodson law suggests that there is a link between arousal levels and performance. Essentially, increased arousal levels can help you do better on exams, but only up to a certain point.

Once these stress levels cross that line, the excessive anxiety you might be experiencing can actually interfere with test performance.

Excessive fear can make it difficult to concentrate and you might struggle to recall things that you have studied. You might feel like all the information you spent some much time reviewing suddenly seems inaccessible in your mind.

You blank out the answers to questions to which you know you know the answers. This inability to concentrate and recall information then contributes to even more anxiety and stress, which only makes it that much harder to focus your attention on the test.

Symptoms of Test Anxiety

The symptoms of test anxiety can vary considerably and range from mild to severe. Some students experience only mild symptoms of test anxiety and are still able to do fairly well on exams. Other students are nearly incapacitated by their anxiety, performing dismally on tests or experiencing panic attacks before or during exams.

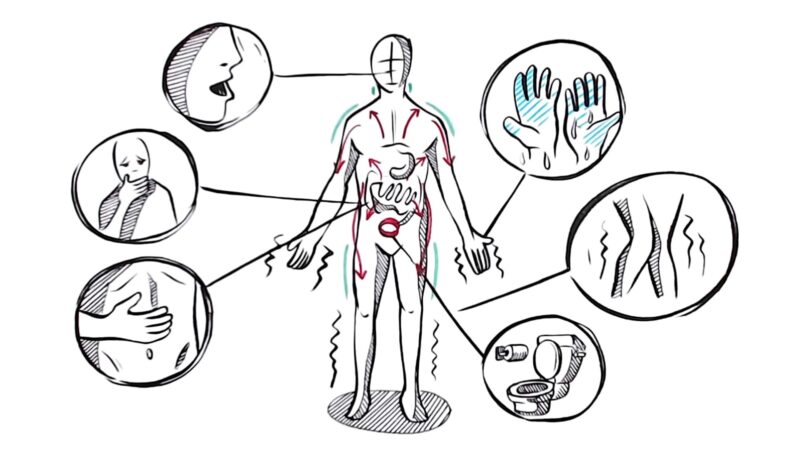

According to the Anxiety and Depression Association of America, symptoms of test anxiety can be physical, behavioral, cognitive, and emotional.

Physical Symptoms

Physical symptoms of test anxiety include sweating, shaking, rapid heartbeat, dry mouth, fainting, and nausea. Sometimes these symptoms might feel like a case of "butterflies" in the stomach, but they can also be more serious symptoms of physical illness such as nausea, diarrhea, or vomiting.

Cognitive and Behavioral Symptoms

Cognitive and behavioral symptoms can include avoiding situations that involve testing. This can involve skipping class or even dropping out of school. In other cases, people might use drugs or alcohol to cope with symptoms of anxiety.

Other cognitive symptoms include memory problems, difficulty concentrating, and negative self-talk .

Emotional Symptoms

Emotional symptoms of test anxiety can include depression, low self-esteem , anger, and a feeling of hopelessness . Fortunately, there are steps that students can take to alleviate these unpleasant and oftentimes harmful symptoms. By learning more about the possible causes of their test anxiety, students can begin to look for helpful solutions.

Is test anxiety a disorder?

Test anxiety is not recognized as a distinct condition in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR). However, it can sometimes occur as a manifestation of another anxiety disorder such as social anxiety disorder , generalized anxiety disorder , or specific phobia .

Causes of Test Anxiety

While test anxiety can be very stressful for students who experience it, many people do not realize that is actually quite common. Nervousness and anxiety are perfectly normal reactions to stress. For some people, however, this fear can become so intense that it actually interferes with their ability to perform well.

So what causes test anxiety? For many students, it can be a combination of things. Poor study habits, poor past test performance, and an underlying anxiety problem can all contribute to test anxiety.

A few potential causes of test anxiety include:

- Fear of failure : If you connect your sense of self-worth to your test scores, the pressure you put on yourself can cause severe test anxiety.

- Poor testing history : If you have done poorly on tests before, either because you didn't study well enough or because you were so anxious, you couldn't remember the answers, this can cause even more anxiety and a negative attitude every time you have to take another test.

- Unpreparedness : If you didn't study or didn't study well enough, this can add to your feeling of anxiety.

Biological Causes

In stressful situations, such as before and during an exam, the body releases a hormone called adrenaline. This helps prepare the body to deal with what is about to happen and is commonly referred to as the "fight-or-flight" response . Essentially, this response prepares you to either stay and deal with the stress or escape the situation entirely.

In a lot of cases, this adrenaline rush is actually a good thing. It helps prepare you to deal effectively with stressful situations, ensuring that you are alert and ready. For some people, however, the symptoms of anxiety they feel can become so excessive that it makes it difficult or even impossible to focus on the test.

Symptoms such as nausea, sweating, and shaking hands can actually make people feel even more nervous, especially if they become preoccupied with these test anxiety symptoms.

Mental Causes

In addition to the underlying biological causes of anxiety, there are many mental factors that can play a role in this condition. Student expectations are one major mental factor. For example, if a student believes that she will perform poorly on an exam, she is far more likely to become anxious before and during a test.

Test anxiety can also become a vicious cycle. After experiencing anxiety during one exam, students may become so fearful about it happening again that they actually become even more anxious during the next exam. After repeatedly enduring test anxiety, students may begin to feel that they have no power to change the situation, a phenomenon known as learned helplessness .

Three common causes of test anxiety include behavioral, biological, and psychological factors. Behaviors like failing to prepare can play a role, but the body's biological response to stress can also create feelings of anxiety. Mental factors, such as self-belief and negative thinking, can also lead to test anxiety.

How to Overcome Test Anxiety

So what exactly can you do to prevent or minimize test anxiety? Here are some strategies to help cope:

- Avoid the perfectionist trap . Don't expect to be perfect. We all make mistakes and that's okay. Knowing you've done your best and worked hard is really all that matters, not perfection.

- Banish the negative thoughts . If you start to have anxious or defeated thoughts, such as "I'm not good enough," "I didn't study hard enough," or "I can't do this," push those thoughts away and replace them with positive thoughts. "I can do this," "I know the material," and "I studied hard," can go far in helping to manage your stress level when taking a test.

- Get enough sleep . A good night's sleep will help your concentration and memory.

- Make sure you're prepared . That means studying for the test early until you feel comfortable with the material. Don't wait until the night before. If you aren't sure how to study, ask your teacher or parent for help. Being prepared will boost your confidence, which will lessen your test anxiety.

- Take deep breaths . If you start to feel anxious while you're taking your test, deep breathing may be useful for reducing anxiety. Breathe deeply in through your nose and out through your mouth. Work through each question or problem one at a time, taking a deep breath in between each one as needed. Making sure you are giving your lungs plenty of oxygen can help your focus and sense of calm.

Therapy and Medications Can Also Help

If you need extra support, make an appointment with your school counselor or primary care physician.

Depending on the severity of your symptoms, your physician may also recommend cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) , anti-anxiety medications, or a combination of both. CBT focuses on helping people change both the behaviors and underlying thoughts that contribute to unwanted behaviors or feelings.

Test anxiety can be unpleasant and stressful, but it is also treatable. If you believe that test anxiety is interfering with your ability to perform well, try utilizing some self-help strategies designed to help you manage and lower your anxiety levels.

If you or a loved one are struggling with an anxiety disorder, contact the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) National Helpline at 1-800-662-4357 for information on support and treatment facilities in your area.

For more mental health resources, see our National Helpline Database .

Doherty JH, Wenderoth MP. Implementing an expressive writing intervention for test anxiety in a large college course . J Microbiol Biol Educ . 2017;18(2):18.2.39. doi:10.1128/jmbe.v18i2.1307

American Psychological Association. Performance anxiety .

Porcelli AJ, Delgado MR. Stress and decision making: effects on valuation, learning, and risk-taking . Curr Opin Behav Sci . 2017;14:33-39. doi:10.1016/j.cobeha.2016.11.015

Henderson RK, Snyder HR, Gupta T, Banich MT. When does stress help or harm? The effects of stress controllability and subjective stress response on stroop performance . Front Psychol . 2012;3:179. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00179

Anxiety and Depression Association of America. Test anxiety .

Chand SP, Marwaha R. Anxiety . In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing.

Spielberger, CD, Anton, WD, & Bedell, J. The nature and treatment of test anxiety. In M. Zuckerman & CD. Spielberger (Eds.), Emotions and Anxiety: New Concepts, Methods, and Applications. London: Psychology Press; 2015.

Cleveland Clinic. How sleeping better can give your brain a big boost (+ tips for making that happen) .

Yusefzadeh H, Amirzadeh Iranagh J, Nabilou B. The effect of study preparation on test anxiety and performance: a quasi-experimental study . Adv Med Educ Pract . 2019;10:245-251. doi:10.2147/AMEP.S192053

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Test Anxiety

- Categories: Engaging with Courses , Self-Regulation

Test anxiety can appear before, during, or after an exam. When it rears its ugly head, remember to practice self-compassion, to focus on helpful strategies for success, and to seek help when needed.

Ahead of an exam, students experience test anxiety for many reasons. Perfectionism leads some students to believe that their test performance won’t be good enough to meet their exacting standards. For other students, they are not familiar enough with the test material, resulting in a lack of confidence about their abilities. Some students might not have studied at all because their belief that they will never understand the material well enough has led to procrastination.

While there are many contributors to test anxiety, arming yourself with strategies can help you work your way through it. Preparation, organization, and practice can boost confidence by helping you focus on what you have control over rather than on the “unknowns” posed by your exam.

Strategies for dealing with anxiety before an exam:

At the beginning of the semester, add test dates to your calendar. Taking the time to do this step will enable you to see what assessments are on the horizon and to prepare for them intentionally.

When a test is still a long way out, studying is less likely to make you feel anxious because the stakes of your learning don’t feel as intense or immediate. Even just knowing that you’ve started studying early can do a lot to relieve test anxiety.

Check out the ARC webpage on Memory and Attention for some memorization tips; practicing some of these memorization strategies can help you feel more confident about the effectiveness of your studying.

Take practice tests regularly to check your understanding. Seek out support if you encounter concepts that confuse you, and keep your studies focused on the areas that are most challenging for you.

The teaching staff are there for you – to answer questions and to help you understand the material better.

Take advantage of ARC Peer Tutoring for an additional layer of one-on-one support.

During an exam, it’s natural to feel the effects of increased adrenaline as you try to complete your work. Negative thoughts might circulate, your mind might go blank, or you might fear that you’ll run out of time. To mitigate the impact of these events, come prepared with some strategies to enact in the moment.

Strategies for dealing with anxiety during an exam:

When you start to struggle with a particular problem or feel your mind go blank, it can be easy to imagine the whole test turning into a disaster. When this kind of negative thinking hits you, close your eyes, take a deep breath, and try to imagine seeing your score at the end and being satisfied with the outcome. Give your brain the opportunity to reset. Then, turn back to your exam, but not immediately to the place that made you feel anxious. Instead, try starting a new problem, or look back over one you feel you’ve answered successfully.

It may be that you will have more success by reframing your anxiety than trying to eliminate it. Try to think of your exam as a game! Anxiety and excitement are two sides of the same coin: they both involve high levels of adrenaline. Come up with a “prize” for yourself when you finish the game so that your focus is on winning the prize and not on the grade you will receive on the exam.

One way to combat anxiety during a test is to practice mindful breathing, which is the opposite of the shallow breathing that comes with anxiety and increases distress. Close your eyes, take a deep breath in and out through your nose, and focus on the feeling of the air passing through your nasal passages and lungs. Do this slowly a few times, always pulling your attention back to your breath when it tries to wander to the source of your anxiety. After a few breaths, you will likely feel able to move forward with your exam. Reconnect with your breath as often as you need (and time allows!).

A lot of test anxiety arises from negative self-talk: from telling yourself that you aren’t good enough or smart enough to succeed. When that arises, have some affirmations in mind ahead of time to recite to yourself: “I am prepared for this exam” or “I know this material” or “This is just a test.”

After a test, it’s not uncommon for students to dwell in uncertainty about their grade, experience regret about a lack of preparation, or beat themselves up for a mistake.

Tackling post-test anxiety:

You can’t go back in time and change how you prepared for this exam, but you can change what you will do for future exams. If you were dissatisfied with your preparation for the last exam, figure out what is causing your dissatisfaction. (Did you fail to meet with a tutor? Did you cram the night before? Did you skip some of the reading?) Now devise a plan for addressing those causes before the next exam.

An exam is only a snapshot of your understanding of a specific set of information at a specific moment; it is not a measure of your value or intelligence in an enduring way. Instead of allowing your exam performance to define you, see your tests for what they are: opportunities to learn, not only about the material in question, but also how to approach assessments more successfully in the future!

Grades are a kind of feedback: they tell you how well you understand the material based on what the course wants you to be able to do with it. It can be hard to move on from a grade you’re unhappy with if you don’t understand precisely what you did wrong. Although you can’t change the grade you received (unless the instructor clearly made an error when assessing your work), you can seek more feedback on it. Go to office hours and ask questions about what you missed. Go with an open mind – imagine how the answers might help you do better on a future assessment. Sometimes, you may get information that helps you feel better about your performance (e.g., perhaps most of the class missed the question you’re seeking feedback on). Regardless, if you understand your grade better, you will increase your odds of getting a higher one next time.

Sometimes test anxiety can stem from something more serious.

If you are concerned that your learning and engagement with coursework might be affected by depression, anxiety, or other sources of chronic stress, please reach out to Harvard’s Counseling and Mental Health Services (CAMHS) or another trusted health professional to discuss additional support.

What Is Test Anxiety? The Silent Academic Killer You Never Saw Coming!

Have you ever felt that knot in your stomach before a test? I know that feeling all too well. It’s like a mix of nervousness and unease that can make even the brightest minds stumble. But guess what? You’re not alone in this.

Many of us have experienced what’s called “test anxiety,” and I’m here to help you understand it better. Think of me as your friendly guide through this journey. We’ll unravel what test anxiety really is, why it happens, and most importantly, how you can manage it.

No judgments here – just understanding, care, and some practical tips to make those anxious moments a little more bearable. You’ve got this!

Definition and Basics

Test anxiety is a specialized form of performance anxiety . It’s characterized by an overwhelming sense of worry, nervousness, or unease about an imminent test or exam. This anxiety can take various forms, including physical symptoms like migraines, nausea, and an accelerated heartbeat.

On the emotional and cognitive front, individuals might experience feelings of impending doom, pervasive negative thoughts, and moments where they draw a blank during the test, even if they’ve studied the material thoroughly.

What are the Main Causes?

The origins of test anxiety are diverse and can vary from person to person. Some individuals might have had traumatic experiences with testing in the past, leading to a deeply ingrained fear of similar future events.

For others, the fear stems from the potential repercussions of not performing well, such as missing out on a coveted college spot or losing a scholarship. External factors, like societal expectations or parental pressures, can amplify these feelings, creating an environment where the individual feels as if their entire worth is determined by a single test score.

| Causes of Test Anxiety | Description |

|---|---|

| Fear of Failure | Pressure to meet expectations leads to anxiety about not performing well. |

| Perfectionism | Striving for perfection can create intense anxiety due to high self-imposed standards. |

| Lack of Preparation | Insufficient study time or understanding of the material causes feelings of unpreparedness. |

| Poor Test-Taking Skills | Inadequate strategies for exams result in self-doubt and anxiety during tests. |

| Negative Past Experiences | Previous failures contribute to a negative mindset and anxiety about future exams. |

| High Stakes | Exams with significant consequences amplify anxiety due to future impact. |

| Time Pressure | Exam time limits induce stress, affecting time management under pressure. |

| Social Comparison | Comparing oneself to peers triggers feelings of inadequacy and competitiveness. |

| Lack of Coping Strategies | Ineffective stress management skills make it hard to handle exam pressure. |

| Physiological Factors | Stress responses like rapid heart rate and sweating intensify anxiety. |

| Cognitive Distortions | Negative thought patterns exaggerate the consequences of failure, fueling anxiety. |

| Low Self-Esteem | Doubting abilities and fearing judgment heighten test-related anxiety. |

| Pressure from Parents or Peers | External expectations add stress and anxiety to perform well. |

| Test Format | Unfamiliar formats (e.g., multiple-choice questions) create discomfort and anxiety. |

| General Anxiety Disorder | Pre-existing anxiety tendencies exacerbate anxiety during test situations. |

Physical Symptoms

The body’s reaction to stress, including the stress from test anxiety, can be surprisingly intense. Recognizing these symptoms is pivotal in addressing and managing them.

The Fight or Flight Response

When confronted with a perceived threat, our bodies instinctively activate the “fight or flight” response. This evolutionary survival mechanism can lead to symptoms like:

- pounding heart

- parched mouth

- jittery limbs

While this response was invaluable for our ancestors when facing tangible dangers, it’s less beneficial when the “threat” is an exam paper filled with questions.

Common Physical Manifestations

Beyond the immediate fight or flight response, test anxiety can lead to a range of other physical symptoms. These might encompass:

- stomach disturbances

- profuse sweating

- bouts of dizziness

For some individuals, these symptoms escalate to such an extent that they mirror those of a full-blown panic attack , making it nearly impossible to focus on the task at hand.

Emotional and Cognitive Effects

Test anxiety doesn’t solely manifest physically; it also profoundly impacts our emotional well-being and thought processes.

Negative Self-Talk

One of the most crippling aspects of test anxiety is the spiral of negative self-talk. Thoughts such as “I’m bound to fail” or “I’m just not cut out for this” can dominate the mind.

Over time, this persistent negative self-talk can erode an individual’s self-confidence, reinforcing the cycle of anxiety and making each subsequent testing experience even more daunting.

Feelings of Hopelessness

For some, test anxiety escalates to feelings of hopelessness or even helplessness. This emotional quagmire can make tasks like studying or concentrating seem insurmountable.

It becomes a self-perpetuating cycle: the more despondent one feels, the more intense the anxiety grows, further diminishing the likelihood of a positive outcome.

How to Overcome This Problem?

Test anxiety might seem tough, but it can be overcome. There are tried and tested strategies to help individuals navigate and perform at their peak.

Preparation and Study Techniques

Arguably, the most effective antidote to test anxiety is thorough preparation . This doesn’t merely imply last-minute cramming, but instead adopting effective, long-term study techniques.

Methods like spaced repetition, active recall, and employing mnemonic devices not only enhance retention but also bolster confidence, making the testing experience less intimidating.

Relaxation Techniques

Relaxation techniques, ranging from deep breathing exercises to progressive muscle relaxation and visualization , can be instrumental in calming both the mind and body. Regular practice of these techniques can train the body to relax on cue, diminishing the severity of anxiety symptoms when they arise.

Seeking Professional Help

For some individuals, test anxiety reaches such an intensity that professional intervention becomes essential.

When to Seek Help?

If test anxiety starts to overshadow daily life or causes profound distress, it’s a clear sign that professional help might be needed. This is especially true if an individual has attempted multiple self-help strategies without any discernible improvement or if they’re experiencing symptoms akin to a panic attack.

Therapeutic Interventions

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) stands out as one of the most effective treatments for test anxiety. Through CBT, individuals can learn to challenge and reframe negative thought patterns, cultivate coping strategies, and rebuild their self-confidence. In extreme cases, a psychiatrist might also prescribe medication to manage the most acute symptoms.

The Role of Educators and Parents

Educators and parents are in a unique position to support students as they grapple with test anxiety.

Recognizing the Signs

For educators and parents, being able to identify the signs of test anxiety is paramount. This involves looking beyond just the overt physical symptoms. Behavioral changes, such as a sudden aversion to school, procrastination, or a noticeable decline in academic performance, can all be red flags.

Offering Support

Support can manifest in myriad ways, from providing additional resources or dedicated study time to simply being a compassionate, listening ear. By fostering a nurturing and understanding environment, educators and parents can help students feel more secure, better equipping them to tackle their exams head-on.

The Future of Testing

Alternative assessment methods.

Progressive educational institutions are now veering towards alternative assessment methods. These can include project-based evaluations, oral presentations, or even portfolio assessments.

Such methods provide a more rounded view of a student’s capabilities and can significantly reduce the stress associated with traditional timed exams.

The Move Towards Holistic Education

The educational landscape is gradually shifting towards a more holistic paradigm, where the emphasis is on holistic learning and personal growth rather than mere test scores.

By centering on the entire student experience, educators can foster an environment where test anxiety becomes less prevalent, and students are empowered to reach their full potential.

Can music or aromatherapy help ease test anxiety?

For some, soothing music or calming scents can create a more relaxed environment for studying and test-taking.

How important is a good night’s sleep in managing this problem?

Adequate sleep plays a crucial role in reducing stress and improving cognitive function, helping you handle test anxiety better.

Can peer support groups be beneficial for managing test anxiety?

Yes, talking to peers who understand your feelings can provide emotional support and useful tips.

Are there specific techniques to manage anxiety during online exams?

Applying the same relaxation and focus techniques as in traditional exams can help during online tests as well.

Is it possible to turn this into a positive motivator?

Yes, by reframing anxiety as a natural response and using it to sharpen focus and drive, you can harness it as a positive force.

The Bottom Line

In the end, remember that you’re not alone in this. Test anxiety is a common challenge, and many of us have faced that overwhelming feeling of self-doubt. But take heart, because just like others have triumphed over it, so can you.

Believe in yourself, take a deep breath, and know that with patience, self-care, and the right strategies, you can conquer test anxiety and shine bright on your academic path!

Studying & Test Taking

- Introduction

- What to Study?

- Create a Study Space

- Build Healthy Habits

- Practice Tests

- Mnemonic Devices

- Essay Outlining

- Study Groups

- Preparing for Tests & Exams

- Multiple Choice

- Short Answer

Coping with Test Anxiety

- Feedback Form

- AI Survey for Students

- Co-Curricular Recognition Form

- Faculty Resources

What is Test Anxiety?

Test anxiety is a psychological condition where people experience extreme distress and anxiety in a testing situation .

While many students feel some degree of stress before or during exams, test anxiety can actually impair learning and hurt test performance —too much stress can make it difficult to process information and make connections while you study, which could make it difficult to concentrate and remember information during the test.

In this section, we'll talk about how to recognize and deal with test anxiety so you can find success here at Sheridan!

- Measure Your Test Anxiety

Are you curious to know more about your own test anxiety?

Take this quick quiz to get an idea of how much test anxiety you have right now.

Test Anxiety Overview

Dealing with test anxiety, symptoms of test anxiety.

Test anxiety symptoms can vary between students and range from mild to severe. Some students might experience only mild symptoms of test anxiety and still do fairly well on their tests.

Other students are nearly incapacitated by their anxiety and perform terribly on tests despite knowing the course material—some could even experience panic attacks before or during exams.

Here are a few test anxiety symptoms to watch for in yourself:

- Physical: Headaches, nausea or diarrhea, extreme body temperature changes, excessive sweating, shortness of breath, lightheadedness or fainting, rapid heart beat, and/or dry mouth.

- Emotional: Excessive feelings of fear, disappointment, anger, depression, low self-esteem, uncontrollable crying or laughing, feelings of helplessness.

- Behavioural: Fidgeting, pacing, substance abuse, avoidance (e.g. skipping class).

- Cognitive: Racing thoughts, 'going blank', difficulty concentrating, negative self-talk, feelings of dread, comparing yourself to others, difficulty organizing your thoughts.

Keep in mind that everyone is different and you might experience test anxiety in a completely different way than one of your friends or peers.

Causes of Test Anxiety

For many students, test anxiety can happen due to a combination of things—poor study habits, poor performance on previous tests, and an underlying anxiety problem can all contribute to test anxiety.

A few potential causes can include:

- Fear of failure : If you feel your self-worth is tied to how well you do on a test, this pressure you put on yourself can contribute to severe test anxiety.

- Poor grades on earlier tests: If you haven't done well on previous tests—either because you didn't study well enough or because you were anxious—these experiences can cause even more anxiety and a self-defeating attitude every time you have to take another test.

- Being unprepared : If you didn't study early enough or didn't study well enough, these decisions can add to your current feelings of anxiety.

Learning strategies for better test preparation (i.e. using this module!) is a great first step to reduce your test anxiety.

Finding good stress-management techniques are also crucial for improving mindset and reducing stress and anxiety. If you haven't already, please visit our Mindset Matters module to learn more.

Other techniques you can try include:

- Avoiding perfectionism : Don't expect a perfect grade on your test—we all make mistakes, and that's okay.

- Looking at your " self-talk ": How do you talk to yourself? Are you thinking anxious and defeated thoughts (e.g. "I'm not good enough", "I didn't study hard enough", "I can't do this", etc.)? Try to push those thoughts away and replace them with positive ones (e.g. "I can do this", "I know the material", "I studied hard", etc.).

- Considering your "thought traps": You may find yourself imagining the worst-case scenario or over-generalizing how well you will do on the test—try to focus on the moment. Remember, this is just one test in your entire program.

- Getting enough sleep : A good night's sleep will help your concentration and memory.

- Reducing your physical tension : Practice breathing, meditation, yoga, etc.

Check out the Test Anxiety Booklet from Anxiety Canada to learn more tips and strategies to help you get a hold of your test anxiety!

- Test Anxiety Booklet

Mental Health Supports at Sheridan

If you’re having difficulties managing stress, adjusting to college, or feeling sad and hopeless, please reach out to the Counselling Services team on Sheridan Central.

Sessions are free and confidential .

- Last Updated: Oct 4, 2024 9:46 AM

- URL: https://sheridancollege.libguides.com/studyingandtesttaking

Connect with us

Mind Diagnostics is user-supported. If you buy through a link on the site, we earn a commission from BetterHelp at no cost to you. Learn More

How to Overcome Test Anxiety: Tips and Techniques

Reviewed by Aaron Horn, LMFT · October 26, 2020 ·

- Share to Facebook

- Send as Email

- Copy link Copied

Doing well on tests can serve you well in life. It can help you pass classes, get a degree, or advance your career. Yet, for those with test anxiety, taking a test can feel like torture. These feelings are distressing, and they can affect your performance. Understanding and dealing with this problem can have many benefits. Here’s what you should know if you think you might have test anxiety.

Test Anxiety Statistics

Test anxiety is a significant problem for many students of all ages. Here are a few statistics on test anxiety to give you an idea of its prevalence and effects.

- Between 10 and 40 percent of students experience test anxiety.

- Anxiety disorders affect 18 percent of adults, but only one-third of them seek treatment.

- Increased standardized testing increases test anxiety.

- Among students with test anxiety, those with poor working memory had worse test results than those with good working memory.

Test Anxiety Definition

Test anxiety is a type of performance anxiety that only happens before and during an exam. When you have test anxiety, you feel tense and apprehensive before or during a test. This anxiety can lead to poor test performance.

Test Anxiety Symptoms

If you have test anxiety, you know exactly what the experience is like. The most obvious symptoms may be the feelings that go with it. There are also some symptoms that affect your thinking and your body.

You may feel stressed, helpless, disappointed, fearful, or inadequate. Your thoughts may circle round and round as you dwell on failures from the past. Your mind may go blank or random thoughts may race through your mind.

People with test anxiety usually have trouble concentrating and may procrastinate in preparing for a test. Negative thoughts fill your mind, including thoughts that others may do better than you will.

You may feel physical symptoms too, like headache, increased sweating, nausea, rapid heartbeat, shortness of breath, lightheadedness, and a feeling of faintness.

Why Does Test Anxiety Happen?

Everyone is different, but there are some common reasons why test anxiety happens. First, you may be intensely afraid of failure, especially if the test is critical to your success.

Some people have test anxiety because they don’t prepare well enough. A circular pattern can develop, where putting off studying leads to test anxiety, leading to more lack of preparation.

If you have had bad experiences or low test results in the past, those memories may bring on negative thoughts and feelings when you take tests later.

If you’re a perfectionist, doing poorly on an exam is even more upsetting to you than those who aren’t. Your self-criticism can cause you to do even worse on tests than you would otherwise.

How To Overcome Test Anxiety

Any kind of anxiety can be distressing. The first thing you may want to do is find out how much your anxiety is affecting you. You can take a quick anxiety test online to discover the severity of your symptoms. The next step is to learn how to get rid of test anxiety.

How To Deal With Test Anxiety On Your Own

You can do several things to help yourself with test anxiety. First try out the following tips. Then you can then develop strategies to use when you need to take a test later in life.

Test Anxiety Tips

Use these tips on the day of your exam to stay calm and increase your performance.

- Get a good night’s sleep the night before the exam.

- As you prepare yourself for the day’s exam, turn on some music that makes you feel calm and relaxed.

- Eat a healthy meal or snack before you go.

- Stay hydrated throughout the day of the test. Bring a bottle of water with you to drink right before the exam.

- Limit how much caffeine you drink before the exam to avoid the increased anxiety it can bring.

- Take some time to gather everything you will need during the test. Set them out early rather than trying to remember and grab your pencils, calculator, and any other important items on the way out the door.

- Bring earplugs and use them if noises in the room distract you.

- Get to the exam room early to avoid the tense feeling that comes with rushing to make it in time.

- Choose a seat where you feel most comfortable and can clearly see anything necessary to take the exam, such as questions or math problems on a whiteboard.

- Practice deep breathing whenever you feel tense or anxious during the test.

- Don’t rush to answer. Instead, read the test instructions and each question slowly until you understand them.

- Focus on one question at a time.

- Use systematic muscle relaxation to ease tension in your body.

- Stay mindful of the present moment; avoid getting lost in thoughts of the past or future.

Test Anxiety Strategies

The idea of strategies usually involves planning. Consider what you can do as a part of an overall plan to eliminate test anxiety. Exam anxiety doesn’t have to stop you from achieving your highest goals if you develop an approach that you can use repeatedly.

One strategy is to start studying early. Having test anxiety can make preparation seem like a scary reminder of the test to come. However, when you push past that feeling and study anyway, you can reduce your anxiety before and during the test.

Study in a place that’s similar to the place where you will take the test. Try to find a space set up similarly in an environment with the same types of noises and distractions.

Another strategy is to take some time to develop better studying and test-taking skills. Your school may offer classes or workshops to teach you how to improve your academic abilities. As you become more proficient at studying, your feelings of inadequacy will likely decrease.

Develop self-care habits that help you during classes, self-study, and exams. Make a habit of eating a healthy diet, staying hydrated, exercising regularly, getting enough sleep, and doing things you enjoy.

One of the best strategies for feeling more confident about taking tests is to get in the habit of talking to your teacher or professor about tests as soon as you know they’re coming up. If you can, find out what subjects will be covered, and what level of performance they will require. Uncertainty can increase your anxiety. If you have any questions about the material or the exam, don’t hesitate to ask your teacher.

Can A Therapist Help With Test Anxiety?

Knowing how to overcome test anxiety isn’t always easy. That’s why many people still need help, even after trying the tips and strategies that experts recommend. A counselor can help you develop new thought patterns and beliefs that will help reduce your anxiety.

TIPS TO CONQUER TEST ANXIETY

Improve Your Self-Esteem

People with low self-esteem are more likely to suffer from test anxiety. So, improving your sense of self-worth and acceptance can be extremely beneficial. A part of this process is examining the negative thoughts behind your test anxiety. Then you can replace those unhelpful beliefs with positive thoughts about yourself.

Deal With The Past

A counselor can allow you to express your thoughts and feelings about distressing past events. Whether those events are directly related to test-taking or not, dealing with the past can help you in many ways. It can help you feel calmer, more in control, and more self-confident when you resolve issues that negatively impact you.

Overcome Fears

Many people with test anxiety have panic attacks or intense fears related to test-taking. Overcoming those fears, of course, helps you feel more relaxed during the test. Exposure therapy may be beneficial if you fear being in an exam room.

Here’s an example of how it might work: Your counselor shows you images of rooms where tests are taking place. Next, you sit in a similar space. After that, they may arrange for you to sit quietly in the actual exam room where you will take a test. They are with you all along the way, encouraging you and offering you suggestions for reducing your anxiety. Finally, you go and take a test on your own, and afterward, you discuss it with your counselor to gain even more insights. Sometimes, counselors can use virtual reality programs to start this process.

Set Realistic Expectations

Perfectionism may be the root of your test anxiety. If you expect yourself to ace every test, you are naturally going to worry that there might be some questions you can’t answer or that you’ll make a mistake and blow your perfect record.

However, through counseling, you can explore your expectations and consider whether they are realistic or not. You can learn to accept the idea that expecting perfection is usually unrealistic and doing well is good enough.

Learn Coping Skills And Stress Reduction Techniques

The tips above mentioned some of the coping skills you might learn from a counselor. But during therapy, your counselor can guide you as you practice relaxation techniques. They can help you learn the coping skills that work best for you. They can point you to more specific information and tools to help you manage your stress and anxiety. They can give you worksheets that help put your new knowledge into practice.

What Happens When You Overcome Test Anxiety

Test anxiety can make you miserable. At the same time, it can interfere with your test performance. But once you take the right steps to overcome it, your world may go through a dramatic transformation. You’ll feel more comfortable going into an exam. You’ll probably get higher scores and a higher grade point average. You may even start looking forward to the excitement of taking a test and showing what you know. If you struggle with test anxiety, learning to deal with it may be the first step to greater success and happiness.

DO YOU HAVE ANXIETY?

Everyone has concerns now and then. It’s natural to be a little nervous in situations that involve risk. However, having an anxiety disorder is different. It can seriously affect your daily life and your ability to reach your long-term goals. One way to get an idea of whether you have an anxiety disorder is to take an anxiety test online. Once you know whether you have a significant problem, you can focus on finding out your unique answer to “What is good for anxiety?”

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are signs of test anxiety? What are 3 causes of test anxiety? How do I overcome test anxiety? Is test anxiety a real thing? Why do I cry before exams? Why do learners go blank? How do I gain confidence before a test? Why do people fear tests? What are the two types of test anxiety? How common is test anxiety?

Find out if you have Anxiety

Take this mental health test. It's quick, free, and you'll get your confidential results instantly.

Mental health conditions are real, common, and treatable. If you or someone you know thinks you are suffering from anxiety then take this quick online test or click to learn more about the condition.

Take test Learn more

Related articles

Connecting Anxiety and Anger

Anxiety and anger are two different emotions that can sometimes interact with each other depending on your condition. Technically, anxiety is characterized by feelings of...

DSM-5 Criteria for Generalized Anxiety Disorder

The diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, frequently referred to as the DSM, is used by healthcare providers to categorize and diagnose mental disorders. The..

Battling Sleepless Nights from Anxiety

One sheep...two sheep... Are you finding yourself counting sheep because you're awake all hours of the night? If so, you're not alone. More people find themselves up at night...

Need help? We recommend the following therapists

Shawnda jones.

- Shawnda can help you with: Stress

- Relationship issues

- Family conflicts

- Trauma and abuse

- Anger management

- Bipolar disorder

- Coping with life changes

- Compassion fatigue

Keesha Turner

- Keesha can help you with: Stress

- Parenting issues

- Intimacy-related issues

- Eating disorders

- Self esteem

- Career difficulties

Dr. Zoleikha Gholizadeh

- Zoleikha can help you with: Stress

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Test anxiety is a psychological condition in which people experience extreme distress and anxiety in testing situations. While many people experience some degree of stress and anxiety before and during exams, test anxiety can actually impair learning and hurt test performance.

Test anxiety is a common occurrence in classrooms, affecting the performance of students from kindergarten through college, as well as adults who must take job-related exams. Estimates are that between 40 and 60% of students have significant test anxiety that interferes with their performing up to their capability. What Interventions are ...

Test anxiety is a type of performance anxiety. It can affect everyone from kindergarteners to PhD candidates. If you have test anxiety, you may have anxiety and stress even if you are...

addresses how test anxiety influences adult learners, how it potentially differs from retest anxiety, what we can learn from previous research and theorisation on test

Test anxiety is more than feeling a little nervous before a test. For students who struggle with test anxiety, a bit of pre-exam nervousness turns into debilitating feelings of worry, dread, and fear, which can negatively impact performance. Students can struggle with test anxiety at any age.

A lot of test anxiety arises from negative self-talk: from telling yourself that you aren’t good enough or smart enough to succeed. When that arises, have some affirmations in mind ahead of time to recite to yourself: “I am prepared for this exam” or “I know this material” or “This is just a test.”

Test anxiety is a specialized form of performance anxiety. It’s characterized by an overwhelming sense of worry, nervousness, or unease about an imminent test or exam. This anxiety can take various forms, including physical symptoms like migraines, nausea, and an accelerated heartbeat.

What is Test Anxiety? Test anxiety is a psychological condition where people experience extreme distress and anxiety in a testing situation.

Test anxiety refers to the nervousness you might feel just before or during an exam. Maybe your heart beats a little faster, or your palms start to sweat. Perhaps you feel...

Test anxiety is a type of performance anxiety that only happens before and during an exam. When you have test anxiety, you feel tense and apprehensive before or during a test. This anxiety can lead to poor test performance.