Participatory Action Research at MIT

What is par, participatory action research (par).

By Lawrence Susskind*

This is not to say that applied social science research isn't important. On the contrary, the most serious problems we face today are social and political, not physical. We need to make sure that social science is used to produce prescriptive insights and advice for those trying to promote social change.

Where have social scientists gone wrong?

- First, you have to believe that the two halves of the community are initially the same (and stay the same) during the course of the experiment.

- Second, you must believe that everything else remains constant during the course of the experiment.

- Third, you have to believe that the experimental effort and not something else caused whatever statistically results emerged..

Putting aside ethical and moral concerns about withholding a benefit or imposing something bad on half a community so that someone’s theories can be tested, serious methodological problems remain. Mere correlation isn't a sufficient basis for reshaping public policy or interfering in people's lives. Even more important is the fact that statistical relevance doesn't explain why good or bad things happen. Social scientists should stop pretending that correlation equals causation. They should admit that the complexity and uncertainty involved in the social systems in which we live and work make science-like generalizations about people, communities and institutions extremely unreliable.

Getting social science back on track

PAR produces “actionable” knowledge by focusing on individual situations rather than on statistical analysis of large samples or controlled experiments. All PAR knowledge is "situated." That means it is place- or case-specific. PAR puts a premium on local knowledge (what people in real situation know from their first-hand experience), rather than what experts think. And, PAR measures the success of applied social research in terms of the what client-communities understand , rather than what peer-reviewers think or the replicability of findings. The goal of PAR-like applied social research isn't to generate proof.. On the contrary, the objective of PAR is to generate what Aristotle would have called "practical wisdom" or useable knowledge, believable to those who have to take action if social change is going to occur. Davydd Greenwood and Morten Levin, in Introduction to Action Research: Social Research for Social Change (2006), do a nice job of summarizing the development and current state of PAR.

Many dilemmas still surround participatory action research. These are the focus of ongoing debate among a growing community of PAR scholars and practitioners. Who represents a community, an agency or a client? How should power imbalances in a client-community be handled? How can a "friendly outsider" (i.e. a PAR researcher) convince a client-community that he or she should be trusted? Who should make the final decision about which data ought to be gathered and how findings should be interpreted? How should case specific findings be integrated with what has been learned from other cases or from insights generated by traditional applied social scientists? What role should PAR researchers play in formulating prescriptions for action? Can and should the PAR researcher stay involved with a client-community as its seeks to monitor results and make ongoing adjustments?

Building a community of PAR scholars

The resistance to PAR is strongest among social scientists who yearn to be part of the natural science fraternity, and who are more concerned about being respected by other academics than they are about building the capacity of client-communities to solve the problems they face. In their view, PAR advocates feed right into the hands of natural science skeptics who think putting "social" in front of scientist is equivalent to putting "witch" in front of "doctor." PAR practitioners, for their part, are worried that traditional social scientists are oblivious to the harm they do when they generalize about social and political phenomenon and fail to appreciate the case specific implications of their findings.

We want to initiate a different conversation. PAR teachers and practitioners should focus on explaining to their potential client-communities what they do, and why they do it (and why it would be best to work with PAR researchers rather than traditional social scientists). They should do more to codify the ethical norms that guide PAR in practice so they can be held accountable. And, they should think hard about the best ways of integrating what PAR teaches about case specific situations with the kinds of generalizations that traditional social scientists produce. Finally, we believe that graduate students interested in PAR should also seek to master a range of traditional science research methods. Mixed methods can yield valuable insights.

*Lawrence Susskind is Ford Professor of Urban and Environmental Planning in the Department of Urban Studies and Planning at MIT. He has been a member of the MIT faculty for more than 40 years. He is also Vice-Chair of the Program on Negotiation at Harvard Law School and Founder/Chief Knowledge Officer of the Consensus Building Institute.

[1] A number of authors have done a masterful job spelling out all the reasons why social scientists should stop aspiring to be natural scientists. See Bent Flyvbjerg’s books Real Social Science (2012) and Making Social Science Matter (2001) for a full explanation.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 27 April 2023

Participatory action research

- Flora Cornish ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3404-9385 1 ,

- Nancy Breton ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8388-0458 1 ,

- Ulises Moreno-Tabarez ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3504-8624 2 ,

- Jenna Delgado 3 ,

- Mohi Rua 4 ,

- Ama de-Graft Aikins 5 &

- Darrin Hodgetts 6

Nature Reviews Methods Primers volume 3 , Article number: 34 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

91k Accesses

91 Citations

58 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Communication

- Developing world

Participatory action research (PAR) is an approach to research that prioritizes the value of experiential knowledge for tackling problems caused by unequal and harmful social systems, and for envisioning and implementing alternatives. PAR involves the participation and leadership of those people experiencing issues, who take action to produce emancipatory social change, through conducting systematic research to generate new knowledge. This Primer sets out key considerations for the design of a PAR project. The core of the Primer introduces six building blocks for PAR project design: building relationships; establishing working practices; establishing a common understanding of the issue; observing, gathering and generating materials; collaborative analysis; and planning and taking action. We discuss key challenges faced by PAR projects, namely, mismatches with institutional research infrastructure; risks of co-option; power inequalities; and the decentralizing of control. To counter such challenges, PAR researchers may build PAR-friendly networks of people and infrastructures; cultivate a critical community to hold them to account; use critical reflexivity; redistribute powers; and learn to trust the process. PAR’s societal contribution and methodological development, we argue, can best be advanced by engaging with contemporary social movements that demand the redressingl of inequities and the recognition of situated expertise.

Similar content being viewed by others

Mapping the community: use of research evidence in policy and practice

Negotiating the ethical-political dimensions of research methods: a key competency in mixed methods, inter- and transdisciplinary, and co-production research

Structured output methods and environmental issues: perspectives on co-created bottom-up and ‘sideways’ science

Introduction.

For the authors of this Primer, participatory action research (PAR) is a scholar–activist research approach that brings together community members, activists and scholars to co-create knowledge and social change in tandem 1 , 2 . PAR is a collaborative, iterative, often open-ended and unpredictable endeavour, which prioritizes the expertise of those experiencing a social issue and uses systematic research methodologies to generate new insights. Relationships are central. PAR typically involves collaboration between a community with lived experience of a social issue and professional researchers, often based in universities, who contribute relevant knowledge, skills, resources and networks. PAR is not a research process driven by the imperative to generate knowledge for scientific progress, or knowledge for knowledge’s sake; it is a process for generating knowledge-for-action and knowledge-through-action, in service of goals of specific communities. The position of a PAR scholar is not easy and is constantly tested, as PAR projects and roles straddle university and community boundaries, involving unequal power relations and multiple, sometimes conflicting interests. This Primer aims to support researchers in preparing a PAR project, by providing a scaffold to navigate the processes through which PAR can help us to collaboratively envisage and enact emancipatory futures.

We consider PAR an emancipatory form of scholarship 1 . Emancipatory scholarship is driven by interest in tackling injustices and building futures supportive of human thriving, rather than objectivity and neutrality. It uses research not primarily to communicate with academic experts but to inform grassroots collective action. Many users of PAR aspire to projects of liberation and/or transformation . Users are likely to be critical of research that perpetuates oppressive power relations, whether within the research relationships themselves or in a project’s messages or outcomes, often aiming to trouble or transform power relations. PAR projects are usually concerned with developments not only in knowledge but also in action and in participants’ capacities, capabilities and performances.

PAR does not follow a set research design or particular methodology, but constitutes a strategic rallying point for collaborative, impactful, contextually situated and inclusive efforts to document, interpret and address complex systemic problems 3 . The development of PAR is a product of intellectual and activist work bridging universities and communities, with separate genealogies in several Indigenous 4 , 5 , Latin American 6 , 7 , Indian 8 , African 9 , Black feminist 10 , 11 and Euro-American 12 , 13 traditions.

PAR, as an authoritative form of enquiry, became established during the 1970s and 1980s in the context of anti-colonial movements in the Global South. As anti-colonial movements worked to overthrow territorial and economic domination, they also strived to overthrow symbolic and epistemic injustices , ousting the authority of Western science to author knowledge about dominated peoples 4 , 14 . For Indigenous scholars, the development of PAR approaches often comprised an extension of Indigenous traditions of knowledge production that value inclusion and community engagement, while enabling explicit engagements with matters of power, domination and representation 15 . At the same time, exchanges between Latin American and Indian popular education movements produced Orlando Fals Borda’s articulation of PAR as a paradigm in the 1980s. This orientation prioritized people’s participation in producing knowledge, instead of the positioning of local populations as the subject of knowledge production practices imposed by outside experts 16 . Meanwhile, PAR appealed to those inspired by Black and postcolonial feminists who challenged established knowledge hierarchies, arguing for the wisdom of people marginalized by centres of power, who, in the process of survivance, that is, surviving and resisting oppressive social structures, came to know and deconstruct those structures acutely 17 , 18 .

Some Euro-American approaches to PAR are less transformational and more reformist, in the action research paradigm, as developed by Kurt Lewin 19 to enhance organizational efficacy during and after World War II. Action research later gained currency as a popular approach for professionals such as teachers and nurses to develop their own practices, and it tended to focus on relatively small-scale adjustments within a given institutional structure, instead of challenging power relations as in anti-colonial PAR 13 , 20 . In the late twentieth century, participatory research gained currency in academic fields such as participatory development 21 , 22 , participatory health promotion 23 and creative methods 24 . Although participatory research includes participants in the conceptualization, design and conduct of a project, it may not prioritize action and social change to the extent that PAR does. In the early twenty-first century, the development of PAR is occurring through sustained scholarly engagements in anti-colonial 5 , 25 , abolitionist 26 , anti-racist 27 , 28 , gender-expansive 29 , climate activist 30 and other radical social movements.

This Primer bridges these traditions by looking across them for mutual learning but avoiding assimilating them. We hope that readers will bring their own activist and intellectual heritages to inform their use of PAR and adapt and adjust the suggestions we present to meet their needs.

Four key principles

Drawing across its diverse origins, we characterize PAR by four key principles. The first is the authority of direct experience. PAR values the expertise generated through experience, claiming that those who have been marginalized or harmed by current social relations have deep experiential knowledge of those systems and deserve to own and lead initiatives to change them 3 , 5 , 17 , 18 . The second is knowledge in action. Following the tradition of action research, it is through learning from the experience of making changes that PAR generates new knowledge 13 . The third key principle is research as a transformative process. For PAR, the research process is as important as the outcomes; projects aim to create empowering relationships and environments within the research process itself 31 . The final key principle is collaboration through dialogue. PAR’s power comes from harnessing the diverse sets of expertise and capacities of its collaborators through critical dialogues 7 , 8 , 32 .

Because PAR is often unfamiliar, misconstrued or mistrusted by dominant scientific 33 institutions, PAR practitioners may find themselves drawn into competitions and debates set on others’ terms, or into projects interested in securing communities’ participation but not their emancipation. Engaging communities and participants in participatory exercises for the primary purpose of advancing research aims prioritized by a university or others is not, we contend, PAR. We encourage PAR teams to articulate their intellectual and political heritage and aspirations, and agree their core principles, to which they can hold themselves accountable. Such agreements can serve as anchors for decision-making or counterweights to the pull towards inegalitarian or extractive research practices.

Aims of the Primer

The contents of the Primer are shaped by the authors’ commitment to emancipatory, engaged scholarship, and their own experience of PAR, stemming from their scholar-activism with marginalized communities to tackle issues including state neglect, impoverishment, infectious and non-communicable disease epidemics, homelessness, sexual violence, eviction, pollution, dispossession and post-disaster recovery. Collectively, our understanding of PAR is rooted in Indigenous, Black feminist and emancipatory education traditions and diverse personal experiences of privilege and marginalization across dimensions of race, class, gender, sexuality and disability. We use an inclusive understanding of PAR, to include engaging, emancipatory work that does not necessarily use the term PAR, and we aim to showcase some of the diversity of scholar-activism around the globe. The contents of this Primer are suggestions and reflections based on our own experience of PAR and of teaching research methodology. There are multiple ways of conceptualizing and conducting a PAR project. As context-sensitive social change processes, every project will pose new challenges.

This Primer is addressed primarily to university-based PAR researchers, who are likely to work in collaboration with members of communities or organizations or with activists, and are accountable to academic audiences as well as to community audiences. Much expertise in PAR originates outside universities, in community groups and organizations, from whom scholars have much to learn. The Primer aims to familiarize scholars new to PAR and others who may benefit with PAR’s key principles, decision points, practices, challenges, dilemmas, optimizations, limitations and work-arounds. Readers will be able to use our framework of ‘building blocks’ as a guide to designing their projects. We aim to support critical thinking about the challenges of PAR to enable readers to problem-solve independently. The Primer aims to inspire with examples, which we intersperse throughout. To illustrate some of the variety of positive achievements of PAR projects, Box 1 presents three examples.

Box 1 What does participatory action research do?

The Tsui Anaa Project 60 in Accra, Ghana, began as a series of interviews about diabetes experiences in one of Accra’s oldest indigenous communities, Ga Mashie. Over a 12-year period, a team of interdisciplinary researchers expanded the project to a multi-method engagement with a wide range of community members. University and community co-researchers worked to diagnose the burden of chronic conditions, to develop psychosocial interventions for cardiovascular and associated conditions and to critically reflect on long-term goals. A health support group of people living with diabetes and cardiovascular conditions, called Jamestown Health Club (JTHC), was formed, met monthly and contributed as patient advocates to community, city and national non-communicable disease policy. The project has supported graduate collaborators with mixed methods training, community engagement and postgraduate theses advancing the core project purposes.

Buckles, Khedkar and Ghevde 39 were approached by members of the Katkari tribal community in Maharashtra, India, who were concerned about landlords erecting fences around their villages. Using their institutional networks, the academics investigated the villagers’ legal rights to secure tenure and facilitated a series of participatory investigations, through which Katkari villagers developed their own understanding of the inequalities they faced and analysed potential action strategies. Subsequently, through legal challenges, engagement with local politics and emboldened local communities, more than 100 Katkari communities were more secure and better organized 5 years later.

The Morris Justice Project 74 in New York, USA, sought to address stop-and-frisk policing in a neighbourhood local to the City University of New York, where a predominantly Black population was subject to disproportionate and aggressive policing. Local residents surveyed their neighbours to gather evidence on experiences of stop and frisk, compiling their statistics and experiences and sharing them with the local community on the sidewalk, projecting their findings onto public buildings and joining a coalition ‘Communities United for Police Reform’, which successfully campaigned for changes to the city’s policing laws.

Experimentation

This section sets out the core considerations for designing a PAR project.

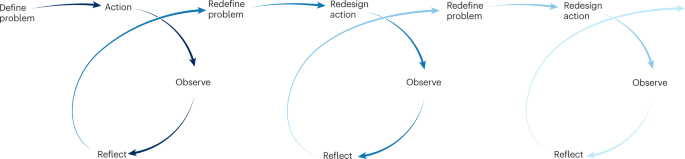

Owing to the intricacies of working within complex human systems in real time, PAR practitioners do not follow a highly proceduralized or linear set of steps 34 . In a cyclical process, teams work together to come to an initial definition of their social problem, design a suitable action, observe and gather information on the results, and then analyse and reflect on the action and its impact, in order to learn, modify their understanding and inform the next iteration of the research–action cycle 3 , 35 (Fig. 1 ). Teams remain open throughout the cycle to repeating or revising earlier steps in response to developments in the field. The fundamental process of building relationships occurs throughout the cycles. These spiral diagrams orient readers towards the central interdependence of processes of participation, action and research and the nonlinear, iterative process of learning by doing 3 , 36 .

Participatory action research develops through a series of cycles, with relationship building as a constant practice. Cycles of research text adapted from ref. 81 , and figure adapted with permission from ref. 82 , SAGE.

Building blocks for PAR research design

We present six building blocks to set out the key design considerations for conducting a PAR project. Each PAR team may address these building blocks in different ways and with different priorities. Table 1 proposes potential questions and indicative goals that are possible markers of progress for each building block. They are not prescriptive or exhaustive but may be a useful starting point, with examples, to prompt new PAR teams’ planning.

Building relationships

‘Relationships first, research second’ is our key principle for PAR project design 37 . Collaborative relationships usually extend beyond a particular PAR project, and it is rare that one PAR project finalizes a desired change. A researcher parachuting in and out may be able to complete a research article, with community cooperation, but will not be able to see through the hard graft of a programme of participatory research towards social change. Hence, individual PAR projects are often nested in long-term collaborations. Such collaborations are strengthened by institutional backing in the form of sustainable staff appointments, formal recognition of the value of university–community partnerships and provision of administrative support. In such a supportive context, opportunities can be created for achievable shorter-term projects to which collaborators or temporary researchers may contribute. The first step of PAR is sometimes described as the entry, but we term this foundational step building relationships to emphasize the longer-term nature of these relationships and their constitutive role throughout a project. PAR scholars may need to work hard with and against their institutions to protect those relationships, monitoring potential collaborations for community benefit rather than knowledge and resource extraction. Trustworthy relationships depend upon scholars being aware, open and honest about their own interests and perspectives.

The motivation for a PAR project may come from university-based or community-based researchers. When university researchers already have a relationship with marginalized communities, they may be approached by community leaders initiating a collaboration 38 , 39 . Alternatively, a university-based researcher may reach out to representatives of communities facing evident problems, to explore common interests and the potential for collaboration 40 . As Indigenous scholars have articulated, communities that have been treated as the subjects or passive objects of research, commodified for the scientific knowledge of distant elites, are suspicious of research and researchers 4 , 41 . Scholars need to be able to satisfy communities’ key questions: Who are you? Why should we trust you? What is in it for our community? Qualifications, scholarly achievements or verbal reassurances are less relevant in this context than past or present valued contributions, participation in a heritage of transformational action or evidence of solidarity with a community’s causes. Being vouched for by a respected community member or collaborator can be invaluable.

Without prior relationships one can start cold, as a stranger, perhaps attending public events, informal meeting places or identifying organizations in which the topic is of interest, and introducing oneself. Strong collaborative relationships are based on mutual trust, which must be earned. It is important to be transparent about our interests and to resist the temptation to over-promise. Good PAR practitioners do not raise unrealistic expectations. Box 2 presents key soft skills for PAR researchers.

Positionality is crucial to PAR relationships. A university-based researcher’s positionalities (including, for example, their gender, race, ethnicity, class, politics, skills, age, life stage, life experiences, assumptions about the problem, experience in research, activism and relationship to the topic) interact with the positionalities of community co-researchers, shaping the collective definition of the problem and appropriate solutions. Positionalities are not fixed, but can be changing, multiple and even contradictory 42 . We have framed categories of university-based and community-based researchers here, but in practice these positionings of ‘insiders’ and ‘outsiders’ are often more complex and shifting 43 . Consideration of diversity is important when building a team to avoid tokenism . For example, identifying which perspectives are included initially and why, and whether members of the team or gatekeepers have privileged access owing to their race, ethnicity, class, gender and/or able-bodiedness.

The centring of community expertise in PAR does not mean that a community is ‘taken for granted’. Communities are sites of the production of similarity and difference, equality and inequalities, and politics. Knowledge that has the status of common sense may itself reproduce inequalities or perpetuate harm. Relatedly, strong PAR projects cultivate reflexivity 44 among both university-based and community-based researchers, to enable a critical engagement with the diversity of points of view, positions of power and stakes in a project. Developing reflexivity may be uncomfortable and challenging, and good PAR projects create a supportive culture for processing such discomfort. Supplementary files 1 and 2 present example exercises that build critical reflexivity.

Box 2 Soft skills of a participatory action researcher

Respect for others’ knowledge and the expertise of experience

Humility and genuine kindness

Ability to be comfortable with discomfort

Sharing power; ceding control

Trusting the process

Acceptance of uncertainty and tensions

Openness to learning from collaborators

Self-awareness and the ability to listen and be confronted

Willingness to take responsibility and to be held accountable

Confidence to identify and challenge power relations

Establishing working practices

Partnerships bring together people with different sets of norms, assumptions, interests, resources, time frames and working practices, all nested in institutional structures and infrastructures that cement those assumptions. University-based researchers often take their own working practices for granted, but partnership working calls for negotiation. Academics often work with very extended time frames for analysis, writing and review before publication, hoping to contribute to gradually shifting agendas, discourses and politics 45 . The urgency of problems that face a community often calls for faster responsiveness. Research and management practices that are normal in a university may not be accessible to people historically marginalized through dimensions that include disability, language, racialization, gender, literacy practices and their intersections 46 . Disrupting historically entrenched power dynamics associated with these concerns can raise discomfort and calls for skilful negotiation. In short, partnership working is a complex art, calling for thoughtful design of joint working practices and a willingness to invest the necessary time.

Making working practices and areas of tension explicit is one useful starting point. Not all issues need to be fully set out and decided at the outset of a project. A foundation of trust, through building relationships in building block 1, allows work to move ahead without every element being pinned down in advance. Supplementary file 1 presents an exercise designed to build working relationships and communicative practices.

Establishing a common understanding of the issue

Co-researchers identify a common issue or problem to address. University-based researchers tend to justify the selection of the research topic with reference to a literature review, whereas in PAR, the topic must be a priority for the community. Problem definition is a key step for PAR teams, where problem does not necessarily mean something negative or a deficit, but refers to the identification of an important issue at stake for a community. The definition of a problem, however, is not always self-evident, and producing a problem definition can be a valid outcome of PAR. In the example of risks of eviction from Buckles, Khedkar and Ghevde 39 (Box 1 ), a small number of Katkari people first experienced the problem in terms of landlords erecting barbed wire fences. Other villages did not perceive the risk of eviction as a big problem compared with their other needs. Facilitating dialogues across villages about their felt problems revealed how land tenure was at the root of several issues, thus mobilizing interest. Problem definitions are political; they imply some forms of action and not others. Discussion and reflexivity about the problem definition are crucial. Compared with other methodologies, the PAR research process is much more public from the outset, and so practices of making key steps explicit, shareable, communicable and negotiable are essential. Supplementary file 3 introduces two participatory tools for collective problem definition.

Consideration of who should be involved in problem definition is important. It may be enough that a small project team works closely together at this stage. Alternatively, group or public meetings may be held, with careful facilitation 5 . Out of dialogue, a PAR team aims to agree on an actionable problem definition, responding to the team’s combination of skills, capacities and priorities. A PAR scholar works across the university–community boundary and thus is accountable to both university values and grassroots communities’ values. PAR scholars should not deny or hide the multiple demands of the role because communities with experience of marginalization are attuned to being manipulated. Surfacing interests and constraints and discussing these reflexively is often a better strategy. Creativity may be required to design projects that meet both academic goals (such as when a project is funded to produce certain outcomes) and the community’s goals.

For example, in the context of a PAR project with residents of a public housing neighbourhood scheduled for demolition and redevelopment, Thurber and colleagues 47 describe how they overcame differences between resident and academic researchers regarding the purposes of their initial survey. The academic team members preferred the data to be anonymous, to maximize the scientific legitimacy of their project (considered valuable for their credibility to policymakers), whereas the resident team wanted to use the opportunity to recruit residents to their cause, by collecting contact details. The team discussed their different objectives and produced the solution of two-person survey teams, one person gathering anonymous data for the research and a second person gathering contact details for the campaign’s contact list.

Articulating research questions is an early milestone. PAR questions prioritize community concerns, so they may differ from academic-driven research questions. For example, Buckles, Khedkar and Ghevde 39 facilitated a participatory process that developed questions along the lines of: What are the impacts of not having a land title for Katkari people? How will stakeholders respond to Katkari organizing, and what steps can Katkari communities take towards the goal of securing tenure? In another case, incarcerated women in New York state, USA, invited university academics to evaluate a local college in prison in the interest of building an empirical argument for the value of educational opportunities in prisons 38 , 48 Like other evaluations, it asked: “What is the impact of college on women in prison?” But instead of looking narrowly at the impact on re-offending as the relevant impact (as prioritized by politicians and policymakers), based on the incarcerated women’s advice, the evaluation tracked other outcomes: women’s well-being within the prison; their relationships with each other and the staff; their children; their sense of achievement; and their agency in their lives after incarceration.

As a PAR project develops, the problem definition and research questions are often refined through the iterative cycles. This evolution does not undermine the value of writing problem definitions and research questions in the early stages, as a collaboration benefits from having a common reference point to build from and from which to negotiate.

Observing, gathering and generating materials

With a common understanding of the problem, PAR teams design ways of observing the details and workings of this problem. PAR is not prescriptive about the methods used to gather or generate observations. Projects often use qualitative methods, such as storytelling, interviewing or ethnography, or participatory methods, such as body mapping, problem trees, guided walks, timelines, diaries, participatory photography and video or participatory theatre. Gathering quantitative data is an option, particularly in the tradition of participatory statistics 49 . Chilisa 5 distinguishes sources of spatial data, time-related data, social data and technical data. The selected methods should be engaging to the community and the co-researchers, suited to answering the research questions and supported by available professional skills. Means of recording the process or products, and of storing those records, need to be agreed, as well as ethical principles. Developing community members’ research skills for data collection and analysis can be a valued contribution to a PAR project, potentially generating longer-term capacities for local research and change-making 50 .

Our selection of data generation methods and their details depends upon the questions we ask. In some cases, methods to explore problem definitions and then to brainstorm potential actions, their risks and benefits will be useful (Supplementary file 3 ). Others may be less prescriptive about problems and solutions, seeking to explore experience in an open-ended way, as a basis for generating new understandings (see Supplementary file 2 for an example reflective participatory exercise).

Less-experienced practitioners may take a naive approach to PAR, which assumes that knowledge should emerge solely from an authentic community devoid of outside ideas. More established PAR researchers, however, work consciously to combine and exchange skills and knowledge through dialogue. Together with communities, we want to produce effective products, and we recognize that doing so may require specific skills. In Marzi’s 51 participatory video project with migrant women in Colombia, she engaged professional film-makers to provide the women with training in filming, editing and professional film production vocabulary. The women were given the role of directors, with the decision-making power over what to include and exclude in their film. In a Photovoice project with Black and Indigenous youth in Toronto, Canada, Tuck and Habtom 25 drew on their prior scholar–activist experience and their critical analysis of scholarship of marginalization, which often uses tropes of victimhood, passivity and sadness. Instead of repeating narratives of damage, they intended to encourage desire-based narratives. They supported their young participants to critically consider which photographs they wanted to include or exclude from public representations. Training participants to be expert users of research techniques does not devalue their existing expertise and skills, but takes seriously their role in co-producing valid, critical knowledge. University-based researchers equally benefit from training in facilitation methods, team development and the history and context of the community.

Data generation is relational, mediated by the positionalities of the researchers involved. As such, researchers position themselves across boundaries, and need to have, or to develop, skills in interpreting across boundaries. In the Tsui Anaa Project (Box 1 ) in Ghana, the project recruited Ga-speaking graduate students as researchers; Ga is the language most widely spoken in the community. The students were recruited not only for their language skills, but also for their Ga cultural sensibilities, reflected in their sense of humour and their intergenerational communicative styles, enabling fluid communication and mutual understanding with the community. In turn, two community representatives were recruited as advocates to represent patient perspectives across university and community boundaries.

University-based researchers trained in methodological rigour may need reminders that the process of a PAR project is as important as the outcome, and is part of the outcome. Facilitation skills are the most crucial skills for PAR practitioners at this stage. Productive facilitation skills encourage open conversation and collective understandings of the problem at hand and how to address it. More specifically, good facilitation requires a sensitivity to the ongoing and competing social context, such as power relations, within the group to help shift power imbalances and enable participation by all 52 . Box 3 presents a PAR project that exemplifies the importance of relationship building in a community arts project.

Box 3 Case study of the BRIDGE Project: relationship building and collective art making as social change

The BRIDGE Project was a 3-week long mosaic-making and dialogue programme for youth aged 14–18 years, in Southern California. For several summers, the project brought together students from different campuses to discuss inclusion, bullying and community. The goal was to help build enduring relationships among young people who otherwise would not have met or interacted, thereby mitigating the racial tensions that existed in their local high schools.

Youth were taught how to make broken tile mosaic artworks, facilitated through community-building exercises. After the first days, as relationships grew, so did the riskiness of the discussion topics. Youth explored ideas and beliefs that contribute to one’s individual sense of identity, followed by discussion of wider social identities around race, class, sex, gender, class, sexual orientation and finally their identities in relationship to others.

The art-making process was structured in a manner that mirrored the building of their relationships. Youth learned mosaic-making skills while creating individual pieces. They were discouraged from collaborating with anyone else until after the individual pieces were completed and they had achieved some proficiency. When discussions transitioned to focus on the relationship their identities had to each other, the facilitators assisted them in creating collaborative mosaics with small groups.

Staff facilitation modelled the relationship-building goal of the project. The collaborative art making was built upon the rule that no one could make any changes without asking for and receiving permission from the person or people who had placed the piece (or pieces) down. To encourage participants to engage with each other it was vital that they each felt comfortable to voice their opinions while simultaneously learning how to be accountable to their collaborators and respectful of others’ relationships to the art making.

The process culminated in the collective creation of a tile mosaic wall mural, which is permanently installed in the host site.

Collaborative analysis

In PAR projects, data collection and analysis are not typically isolated to different phases of research. Instead, a tried and tested approach to collaborative analysis 53 is to use generated data as a basis for reflection on commonalities, patterns, differences, underlying causes or potentials on an ongoing basis. For instance, body mapping, photography, or video projects often proceed through a series of workshops, with small-scale training–data collection–data analysis cycles in each workshop. Participants gather or produce materials in response to a prompt, and then come together to critically discuss the meaning of their productions.

Simultaneously, or later, a more formal data analysis may be employed, using established social science analytical tools such as grounded theory, thematic, content or discourse analysis, or other forms of visual or ethnographic analysis, with options for facilitated co-researcher involvement. The selection of a specific orientation or approach to analysis is often a low priority for community-based co-researchers. It may be appropriate for university-based researchers to take the lead on comprehensive analysis and the derivation of initial messages. Fine and Torre 29 describe the university-based researchers producing a “best bad draft” so that there is something on the table to react to and discuss. Given the multiple iterations of participants’ expressions of experiences and analyses by this stage, the university-based researchers should be in a position that their best bad draft is grounded in a good understanding of local perspectives and should not appear outlandish, one-sided or an imposition of outside ideas.

For the results and recommendations to reflect community interests, it is important to incorporate a step whereby community representatives can critically examine and contribute to emerging findings and core messages for the public, stakeholders or academic audiences.

Planning and taking action

Taking action is an integral part of a PAR process. What counts as action and change is different for each PAR project. Actions could be targeted at a wide range of scales and different stakeholders, with differing intended outcomes. Valid intended outcomes include creating supportive networks to share resources through mutual aid; empowering participants through sharing experiences and making sense of them collectively; using the emotional impact of artistic works to influence policymakers and journalists; mobilizing collective action to build community power; forging a coalition with other activist and advocacy groups; and many others. Selection between the options depends on underlying priorities, values, theories of how social change happens and, crucially, feasibility.

Articulating a theory of change is one way to demonstrate how we intend to bring about changes through designing an action plan. A theory of change identifies an action and a mechanism, directed at producing outcomes, for a target group, in a context. This device has often been used in donor-driven health and development contexts in a rather prescriptive way, but PAR teams can adapt the tool as a scaffolding for being explicit about action plans and as a basis for further discussions and development of those plans. Many health and development organizations (such as Better Evaluation ) have frameworks to help design a theory of change.

Alternatively, a community action plan 5 can serve as a tangible roadmap to produce change, by setting out objectives, strategies, timeline, key actors, required resources and the monitoring and evaluation framework.

Social change is not easy, and existing social systems benefit, some at the expense of others, and are maintained by power relations. In planning for action, analysis of the power relations at stake, the beneficiaries of existing systems and their potential resistance to change is crucial. It is often wise to assess various options for actions, their potential benefits, risks and ways of mitigating those risks. Sometimes a group may collectively decide to settle for relatively secure, and less-risky, small wins but with the building of sufficient power, a group may take on a bigger challenge 54 .

Ethical considerations are fundamental to every aspect of PAR. They include standard research ethics considerations traditionally addressed by research ethics committees or institutional review boards (IRBs), including key principles of avoidance of harm, anonymity and confidentiality, and voluntary informed consent, although these issues may become much more complex than traditionally presented, when working within a PAR framework 55 . PAR studies typically benefit from IRBs that can engage with the relational specificities of a case, with a flexible and iterative approach to research design with communities, instead of being beholden to very strict and narrow procedures. Wilson and colleagues 56 provide a comprehensive review of ethical challenges in PAR.

Beyond procedural research ethics perspectives, relational ethics are important to PAR projects and raise crucial questions regarding the purpose and conduct of knowledge production and application 37 , 57 , 58 . Relational ethics encourage an emphasis on inclusive practices, dialogue, mutual respect and care, collective decision-making and collaborative action 57 . Questions posed by Indigenous scholars seeking to decolonize Western knowledge production practices are pertinent to a relational ethics approach 4 , 28 . These include: Who designs and manages the research process? Whose purposes does the research serve? Whose worldviews are reproduced? Who decides what counts as knowledge? Why is this knowledge produced? Who benefits from this knowledge? Who determines which aspects of the research will be written up, disseminated and used, and how? Addressing such questions requires scholars to attend to the ethical practices of cultivating trusting and reciprocal relationships with participants and ensuring that the organizations, communities and persons involved co-govern and benefit from the project.

Reflecting on the ethics of her PAR project with young undocumented students in the USA, Cahill 55 highlights some of the intensely complex ethical issues of representation that arose and that will face many related projects. Determining what should be shared with which audiences is intensely political and ethical. Cahill’s team considered editing out stories of dropping out to avoid feeding negative stereotypes. They confronted the dilemma of framing a critique of a discriminatory educational system, while simultaneously advocating that this flawed system should include undocumented students. They faced another common dilemma of how to stay true to their structural analysis of the sources of harms, while engaging decision-makers invested in the current status quo. These complex ethical–political issues arise in different forms in many PAR projects. No answer can be prescribed, but scholar–activists can prepare themselves by reading past case studies and being open to challenging debates with co-researchers.

The knowledge built by PAR is explicitly knowledge-for-action, informed by the relational ethical considerations of who and what the knowledge is for. PAR builds both local knowledge and conceptual knowledge. As a first step, PAR can help us to reflect locally, collectively, on our circumstances, priorities, diverse identities, causes of problems and potential routes to tackle them.

Such local knowledge might be represented in the form of statistical findings from a community survey, analyses of participants’ verbal or visual data, or analyses of workshop discussions. Findings may include elements such as an articulation of the status quo of a community issue; a participatory analysis of root causes and/or actionable elements of the problem; a power analysis of stakeholders; asset mapping; assessment of local needs and priorities. Analysis goes beyond the surface problems, to identify underlying roots of problems to inform potential lines of action.

Simultaneously, PAR also advances more global conceptual knowledge. As liberation theorists have noted, developments in societal understandings of inequalities, marginalization and liberation are often led by those battling such processes daily. For example, the young Black and Indigenous participants working with Tuck and Habtom 25 in Toronto, Canada, engaged as co-theorists in their project about the significance of social movements to young people and their post-secondary school futures. Through their photography project, they expressed how place, and its history, particularly histories of settler colonialism, matters in cities — against a more standard view that treated the urban as somehow interchangeable, modern or neutral. The authors argue for altered conceptions of urban and urban education scholarly literatures, in response to this youth-led knowledge.

A key skill in the art of PAR is in creating achievable actions by choosing a project that is engaging and ambitious with achievable elements, even where structures are resistant to change. PAR projects can produce actions across a wide range of scales (from ‘small, local’ to ‘large, structural’) and across different temporal scales. Some PAR projects are part of decades-long programmes. Within those programmes, an individual PAR project, taking place over 12 or 24 months, might make one small step in the process towards long-term change.

For example, an educational project with young people living in communities vulnerable to flooding in Brazil developed a portfolio of actions, including a seminar, a native seeds fair, support to an individual family affected by a landslide, a campaign for a safe environment for a children’s pre-school, a tree nursery at school and influencing the city’s mayor to extend the environmental project to all schools in the area 30 .

Often the ideal scenario is that such actions lead to material changes in the power of a community. Over the course of a 5-year journey, the Katkari community (Box 1 ) worked with PAR researchers to build community power to resist eviction. The community team compiled households’ proof of residence; documented the history of land use and housing; engaged local government about their situations and plans; and participated more actively in village life to cultivate support 39 . The university-based researchers collected land deeds and taught sessions on land rights, local government and how to acquire formal papers. They opened conversations with the local government on legal, ethical and practical issues. Collectively, their legal knowledge and groundwork gave them confidence to remove fencing erected by landlords and to take legal action to regularize their land rights, ultimately leading to 70 applications being made for formal village sites. This comprised a tangible change in the power relation between landlords and the communities. Even here, however, the authors do not simply celebrate their achievements, but recognize that power struggles are ongoing, landlords would continue to aggressively pursue their interests, and, thus, their achievements were provisional and would require vigilance and continued action.

Most crucially, PAR projects aim to develop university-based and community-based researchers’ collective agency, by building their capacities for collaboration, analysis and action. More specifically, collaborators develop multiple transferable skills, which include skills in conducting research, operating technology, designing outputs, leadership, facilitation, budgeting, networking and public speaking 31 , 59 , 60 .

University-based researchers build their own key capacities through exercising and developing skills, including those for collaboration, facilitation, public engagement and impact. Strong PAR projects may build capacities within the university to sustain long-term relationships with community projects, such as modified and improved infrastructures that work well with PAR modalities, appreciation of the value of long-term sustained reciprocal relations and personal and organizational relationships with communities outside the university.

Applications

PAR disrupts the traditional theory–application binary, which usually assumes that abstract knowledge is developed through basic science, to then be interpreted and applied in professional or community contexts. PAR projects are always applied in the sense that they are situated in concrete human and social problems and aim to produce workable local actions. PAR is a very flexible approach. A version of a PAR project could be devised to tackle almost any real-world problem — where the researchers are committed to an emancipatory and participatory epistemology. If one can identify a group of people interested in collectively generating knowledge-for-action in their own context or about their own practices, and as long as the researchers are willing and able to share power, the methods set out in this Primer could be applied to devise a PAR project.

PAR is consonant with participatory movements across multiple disciplines and sectors, and thus finds many intellectual homes. Its application is supported by social movements for inclusion, equity, representation of multiple voices, empowerment and emancipation. For instance, PAR responds to the value “nothing about us without us”, which has become a central tenet of disability studies. In youth studies, PAR is used to enhance the power of young people’s voices. In development studies, PAR has a long foundation as part of the demand for greater participation, to support locally appropriate, equitable and locally owned changes. In health-care research, PAR is used by communities of health professionals to reflect and improve on their own practices. PAR is used by groups of health-care service users or survivors to give a greater collective power to the voices of those at the sharp end of health care, often delegitimized by medical power. In environmental sciences, PAR can support local communities to take action to protect their environments. In community psychology, PAR is valued for its ability to nurture supportive and inclusive processes. In summary, PAR can be applied in a huge variety of contexts in which local ownership of research is valued.

Limitations to PAR’s application often stem from the institutional context. In certain (often dominant) academic circles, local knowledge is not valued, and contextually situated, problem-focused, research may be considered niche, applied or not generalizable. Hence, research institutions may not be set up to be responsive to a community’s situation or needs or to support scholar–activists working at the research–action boundary. Further, those who benefit from, or are comfortable with, the status quo of a community may actively resist attempts at change from below and may undermine PAR projects. In other cases, where a community is very divided or dispersed, PAR may not be the right approach. There are plenty of examples of PAR projects floundering, failing to create an active group or to achieve change, or completely falling through. Even such failures, however, shed light on the conditions of communities and the power relations they inhabit and offer lessons on ways of working and not working with groups in those situations.

Reproducibility and data deposition

Certain aspects of the open science movement can be productively engaged from within a PAR framework, whereas others are incompatible. A key issue is that PAR researchers do not strive for reproducibility, and many would contest the applicability of this construct. Nonetheless, there may be resonances between the open science principle of making information publicly available for re-use and those PAR projects that aim to render visible and audible the experience of a historically under-represented or mis-represented community. PAR projects that seek to represent previously hidden realities of, for example, environmental degradation, discriminatory experiences at the hands of public services, the social history of a traditionally marginalized group, or their neglected achievements, may consider creating and making public robust databases of information, or social history archives, with explicit informed permission of the relevant communities. For such projects, making knowledge accessible is an essential part of the action. Publicly relevant information should not be sequestered behind paywalls. PAR practitioners should thus plan carefully for cataloguing, storing and archiving information, and maintaining archives.

On the other hand, however, a blanket assumption that all data should be made freely available is rarely appropriate in a PAR project and may come into conflict with ethical priorities. Protecting participants’ confidentiality can mean that data cannot be made public. Protecting a community from reputational harm, in the context of widespread dehumanization, criminalization or stigmatization of dispossessed groups, may require protection of their privacy, especially if their lives or coping strategies are already pathologized 25 . Empirical materials do not belong to university-based researchers as data and cannot be treated as an academic commodity to be opened to other researchers. Open science practices should not extend to the opening of marginalized communities to knowledge exploitation by university researchers.

The principle of reproducibility is not intuitively meaningful to PAR projects, given their situated nature, that is, the fact that PAR is inherently embedded in particular concrete contexts and relationships 61 . Beyond reproducibility, other forms of mutual learning and cross-case learning are vitally important. We see increasing research fatigue in communities used, extractively, for research that does not benefit them. PAR teams should assess what research has been done in a setting to avoid duplication and wasting people’s time and should clearly prioritize community benefit. At the same time, PAR projects also aspire to produce knowledge with wider implications, typically discussed under the term generalizability or transferability. They do so by articulating how the project speaks to social, political, theoretical and methodological debates taking place in wider knowledge communities, in a form of “communicative generalisation” 62 . Collaborating and sharing experiences across PAR sites through visits, exchanges and joint analysis can help to generalize experiences 30 , 61 .

Limitations and optimizations

PAR projects often challenge the social structures that reproduce established power relations. In this section, we outline common challenges to PAR projects, to prompt early reflection. When to apply a workaround, compromise, concede, refuse or regroup and change strategy are decisions that each PAR team should make collectively. We do not have answers to all the concerns raised but offer mitigations that have been found useful.

Institutional infrastructure

Universities’ interests in partnerships with communities, local relevance, being outward-facing, public engagement and achieving social impact can help to create a supportive environment for PAR research. Simultaneously, university bureaucracies and knowledge hierarchies that prize their scientists as individuals rather than collaborators and that prioritize the methods of dominant science can undermine PAR projects 63 . When Cowan, Kühlbrandt and Riazuddin 45 proposed using gaming, drama, fiction and film-making for a project engaging young people in thinking about scientific futures, a grants manager responded “But this project can’t just be about having fun activities for kids — where is the research in what you’re proposing?” Research infrastructures are often slow and reluctant to adapt to innovations in creative research approaches.

Research institutions’ funding time frames are also often out of sync with those of communities — being too extended in some ways and too short in others 45 , 64 . Securing funding takes months and years, especially if there are initial rejections or setbacks. Publishing findings takes further years. For community-based partners, a year is a long time to wait and to maintain people’s interest. On the other hand, grant funding for one-off projects over a year or two (or even five) is rarely sufficient to create anything sustainable, reasserting precarity and short-termism. Institutions can better support PAR through infrastructure such as bridging funds between grants, secure staff appointments and institutional recognition and resources for community partners.

University infrastructures can value the long-term partnership working of PAR scholars by recognizing partnership-building as a respected element of an academic career and recognizing collaborative research as much as individual academic celebrity. Where research infrastructures are unsupportive, building relationships within the university with like-minded professional and academic colleagues, to share work-arounds and advocate collectively, can be very helpful. Other colleagues might have developed mechanisms to pay co-researchers, or to pay in advance for refreshments, speed up disbursement of funds, or deal with an ethics committee, IRB, finance office or thesis examiner who misunderstands participatory research. PAR scholars can find support in university structures beyond the research infrastructure, such as those concerned with knowledge exchange and impact, campus–community partnerships, extension activities, public engagement or diversity and inclusion 64 . If PAR is institutionally marginalized, exploring and identifying these work-arounds is extremely labour intensive and depends on the cultivation of human, social and cultural capital over many years, which is not normally available to graduate students or precariously employed researchers. Thus, for PAR to be realized, institutional commitment is vital.

Co-option by powerful structures

When PAR takes place in collaboration or engagement with powerful institutions such as government departments, health services, religious organizations, charities or private companies, co-option is a significant risk. Such organizations experience social pressure to be inclusive, diverse, responsive to communities and participatory, so they may be tempted to engage communities in consultation, without redistributing power. For instance, when ‘photovoice’ projects invite politicians to exhibitions of photographs, their activity may be co-opted to serving the politician’s interest in being seen to express support, but result in no further action. There is a risk that using PAR in such a setting risks tokenizing marginalized voices 65 . In one of our current projects, co-researchers explore the framing of sexual violence interventions in Zambia, aiming to promote greater community agency and reduce the centrality of approaches dominated by the Global North 66 . One of the most challenging dilemmas is the need to involve current policymakers in discussions without alienating them. The advice to ‘be realistic’, ‘be reasonable’ or ‘play the game’ to keep existing power brokers at the table creates one of the most difficult tensions for PAR scholars 48 .

We also caution against scholars idealizing PAR as an ideal, egalitarian, inclusive or perfect process. The term ‘participation’ has become a policy buzzword, invoked in a vaguely positive way to strengthen an organization’s case that they have listened to people. It can equally be used by researchers to claim a moral high ground without disrupting power relations. Depriving words of their associated actions, Freire 7 warns us, leads to ‘empty blah’, because words gain their meaning in being harnessed to action. Labelling our work PAR does not make it emancipatory, without emancipatory action. Equally, Freire cautions against acting without the necessary critical reflection.

To avoid romanticization or co-option, PAR practitioners benefit from being held accountable to their shared principles and commitments by their critical networks and collaborators. Our commitments to community colleagues and to action should be as real for us as any institutional pressures on us. Creating an environment for that accountability is vital. Box 4 offers a project exemplar featuring key considerations regarding power concerns.

Box 4 Case study: participatory power and its vulnerability

Júba Wajiín is a pueblo in a rural mountainous region in the lands now called Guerrero, Mexico, long inhabited by the Me’phaa people, who have fiercely resisted precolonial, colonial and postcolonial displacement and dispossession. Using collective participatory action methods, this small pueblo launched and won a long legal battle that now challenges extractive mining practices.

Between 2001 and 2012, the Mexican government awarded massive mining concessions to mining companies. The people of Júba Wajiín discovered in mid-2013 that, unbeknown to them, concessions for mining exploration of their lands had been awarded to the British-based mining company Horschild Mexico. They engaged human rights activists who used participatory action research methods to create awareness and to launch a legal battle. Tlachinollan, a regional human rights organization, held legal counselling workshops and meetings with local authorities and community elders.

The courts initially rejected the case by denying that residents could be identified as Indigenous because they practised Catholicism and spoke Spanish. A media organization, La Sandia Digital , supported the community to collectively document their syncretic religious and spiritual practices, their ability to speak Mhe’paa language and their longstanding agrarian use of the territory. They produced a documentary film Juba Wajiin: Resistencia en la Montaña , providing visual legal evidence.

After winning in the District court, they took the case to the Supreme Court, asking it to review the legality and validity of the mining concessions. Horschild, along with other mining companies, stopped contesting the case, which led to the concessions being null and void.

The broader question of Indigenous peoples’ territorial rights continued in the courts until mid-2022 when the Supreme Court ruled that Indigenous peoples had the constitutional right to be consulted before any mining activities in their territory. This was a win, but a partial one. ‘Consultations’ are often manipulated by state and private sectors, particularly among groups experiencing dire impoverishment. Júba Wajiín’s strategies proved successful but the struggle against displacement and dispossession is continual.

Power inequalities within PAR

Power inequalities also affect PAR teams and communities. For all the emphasis on egalitarian relationships and dialogue, communities and PAR teams are typically composed of actors with unequal capacities and powers, introducing highly complex challenges for PAR teams.

Most frequently, university-based researchers engaging with marginalized communities do not themselves share many aspects of the identities or life experiences of those communities. They often occupy different, often more privileged, social networks, income brackets, racialized identities, skill sets and access to resources. Evidently, the premise of PAR is that people with different lives can productively collaborate, but gulfs in life experience and privilege can yield difficult tensions and challenges. Expressions of discomfort, dissatisfaction or anger in PAR projects are often indicative of power inequalities and an opportunity to interrogate and challenge hierarchies. Scholars must work hard to undo their assumptions about where expertise and insights may lie. A first step can be to develop an analysis of a scholar’s own participation in the perpetuation of inequalities. Projects can be designed to intentionally redistribute power, by redistributing skills, responsibilities and authority, or by redesigning core activities to be more widely accessible. For instance, Marzi 51 in a participatory video project, used role swapping to distribute the leadership roles of chairing meetings, choosing themes for focus and editing, among all the participants.

Within communities, there are also power asymmetries. The term ‘community participation’ itself risks homogenizing a community, such that one or a small number of representatives are taken to qualify as the community. Yet, communities are characterized by diversity as much as by commonality, with differences across sociological lines such as class, race, gender, age, occupation, housing tenure and health status. Having the time, resources and ability to participate is unlikely to be evenly distributed. Some people need to devote their limited time to survival and care of others. For some, the embodied realities of health conditions and disabilities make participation in research projects difficult or undesirable 67 . If there are benefits attached to participation, careful attention to the distribution of such benefits is needed, as well as critical awareness of the positionality of those involved and those excluded. Active efforts to maximize accessibility are important, including paying participants for their valued time; providing accommodations for people with health conditions, disabilities, caring responsibilities or other specific needs; and designing participatory activities that are intuitive to a community’s typical modes of communication.

Lack of control and unpredictability

For researchers accustomed to leading research by taking responsibility to drive a project to completion, using the most rigorous methods possible, to achieve stated objectives, the collaborative, iterative nature of PAR can raise personal challenges. Sense 68 likens the facilitative role of a PAR practitioner to “trying to drive the bus from the rear passenger seat—wanting to genuinely participate as a passenger but still wanting some degree of control over the destination”. PAR works best with collaborative approaches to leadership and identities among co-researchers as active team members, facilitators and participants in a research setting, prepared to be flexible and responsive to provocations from the situation and from co-researchers and to adjust project plans accordingly 28 , 68 , 69 . The complexities involved in balancing control issues foreground the importance of reflexive practice for all team members to learn together through dialogue 70 . Training and socialization into collaborative approaches to leadership and partnership are crucial supports. Well-functioning collaborative ways of working are also vital, as their trusted structure can allow co-researchers to ‘trust the process’, and accept uncertainties, differing perspectives, changes of emphasis and disruptions of assumptions. We often want surprises in PAR projects, as they show that we are learning something new, and so we need to be prepared to accept disruption.

The PAR outlook is caught up in the ongoing history of the push and pull of popular movements for the recognition of local knowledge and elite movements to centralize authority and power in frameworks such as universal science, professional ownership of expertise, government authority or evidence-based policy. As a named methodological paradigm, PAR gained legitimacy and recognition during the 1980s, with origins in popular education for development, led by scholars from the Global South 16 , 32 , and taken up in the more Global-North-dominated field of international development, where the failings of externally imposed, contextually insensitive development solutions had become undeniable 21 . Over the decades, PAR has both participated in radical social movements and risked co-option and depoliticization as it became championed by powerful institutions, and it is in this light that we consider PAR’s relation to three contemporary societal movements.

Decolonizing or re-powering

The development of PAR took place in tandem with anti-colonial movements and discourses during the 1970s and 1980s, in which the colonization of land, people and knowledge were all at stake. During the mid-2010s, calls for decolonization of the university were forced onto the agenda of the powerful by various groups, including African students and youth leading the ‘Rhodes Must Fall’, ‘Fees must Fall’ and ‘Gandhi must Fall’ movements 71 , followed by the eruption of Black Lives Matter protests in 2020 (ref. 72 ). PAR is a methodology that stands to contribute to decolonization-colonization through the development of alternatives to centralizing knowledge and power. As such, the vitality of local and global movements demanding recognition of grassroots knowledge and the dismantling of oppressive historical power–knowledge systems heralds many openings and exciting potential collaborations and causes for PAR practitioners 73 , 74 . As these demands make themselves felt in powerful institutions, they create openings for PAR.

Yet, just as PAR has been subject to co-option and depoliticization, the concept of decolonization too is at risk of appropriation by dominant groups and further tokenization of Indigenous groups, as universities, government departments and global health institutions absorb the concept, fitting it into their existing power structures 41 , 75 . In this context, Indigenous theorists in Aotearoa/New Zealand are working on an alternative concept of ‘re-powering Indigenous knowledge’ instead of ‘decolonizing knowledge’. By doing so, they centre Indigenous people and their knowledge, instead of the knowledge or actions of colonizers, and foreground the necessity of changes to power relations. African and African American scholars working on African heritage and political agency have drawn on the Akan philosophy of Sankofa for a similar purpose 76 . Sankofa derives from a Twi proverb Se wo were fi na wosan kofa a yenkyiri (It is not taboo to fetch what is at risk of being left behind). Going back to fetch what is lost is a self-grounded act that draws on the riches of Indigenous history to re-imagine and restructure the future 77 . It is also an act independent of the colonial and colonizing gaze. Contributing to a mid-twenty-first century re-powering community knowledge is a promising vision for PAR. More broadly, the loud voices and visionary leadership of contemporary anti-racist, anti-colonial, Indigenous, intersectional feminist and other emancipatory movements provide a vibrant context to re-invent and renew PAR.

Co-production

In fields concerned with health and public service provision, a renewed discourse of respectful engagement with communities and service users has centred in recent years on the concept of co-production 78 . In past iterations, concepts such as citizen engagement, patient participation, community participation and community mobilization had a similar role. Participatory methods have proved their relevance within such contexts, for example, providing actionable and wise insights to clinicians seeking to learn from patients, or to providers of social services seeking to target their services better. Thus, the introduction of co-production may create a receptive environment for PAR in public services. Yet again, if users are participating in something, critical PAR scholars should question in which structures they are participating, instantiating which power relations and to whose benefit. PAR scholars can find themselves compromised by institutional requirements. Identifying potential compromises, lines that cannot be crossed and areas where compromises can be made; negotiating with institutional orders; and navigating discomfort and even conflict are key skills for practitioners of PAR within institutional settings.

One approach to engaging with institutional structures has been to gather evidence for the value of PAR, according to the measures and methods of dominant science. Anyon and colleagues 59 systematically reviewed the Youth PAR literature in the United States. They found emerging evidence that PAR produces positive outcomes for youth and argued for further research using experimental designs to provide harder evidence. They make the pragmatic argument that funding bodies require certain forms of evidence to justify funding, and so PAR would benefit by playing by those rules.

A different approach, grounded in politics rather than the academy, situates co-production as sustained by democratic struggles. In the context of sustainability research in the Amazon, for instance, Perz and colleagues 79 argue that the days of externally driven research are past. Mobilization by community associations, Indigenous federations, producer cooperatives and labour unions to demand influence over the governance of natural resources goes hand in hand with expectations of local leadership and ownership of research, often implemented through PAR. These approaches critically question the desirability of institutional, external funding or even non-monetary support for a particular PAR project.

Global–local inequality and solidarity

Insufferable global and local inequalities continue to grow, intensified by climate catastrophes, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and extreme concentrations of wealth and political influence, and contested by increasingly impactful analyses, protests and refusals by those disadvantaged and discriminated against. Considering the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on PAR projects, Auerbach and colleagues 64 identify increasing marketization and austerity in some universities, and the material context of growing pressure on marginalized communities to simply meet their needs for survival, leaving little capacity for participating in and building long-term partnerships. They describe university-based researchers relying on their own capacities to invent new modes of digital collaboration and nourish their partnerships with communities, often despite limited institutional support.