What Is Task Analysis in Special Education?

Have you ever had difficulty doing a task that others thought was straightforward? Perhaps you had problems tying your shoes or writing simple sentences—some children in special education deal with these challenges regularly. However, task analysis is a helpful tool for teachers and other adults to help students. Students can succeed and develop their talents by breaking down challenging tasks into smaller, more manageable steps. In this blog post, we’ll examine the benefits of task analysis in special education and provide some sound ideas for implementing it in the classroom. So grab a seat and get ready to learn what task analysis is in special education and how task analysis could help all students reach their full potential!

What is Task Analysis in Special Education?

I’ll go into more detail about task analysis in education and how it’s applied to special education .

As a teaching strategy, task analysis entails dissecting difficult activities into simpler, more doable pieces. As it enables children who struggle with executive functioning , attention, and other learning challenges to learn and complete activities successfully, it is a widely utilized instructional method in special education.

When a teacher or therapist uses task analysis, they determine the task’s ultimate objective and then examine each step necessary to achieve that result. To better understand and identify problematic behaviors and their functions, they might conduct a Functional Behavior Assessment . For the student to use as a reference while working on the assignment, they can make a written or visual list of these steps. This list might assist the student in keeping track of their progress and self-evaluate their work.

For several reasons, task analysis is advantageous for special education pupils. First, it assists pupils in breaking down difficult activities into smaller, easier-to-follow steps, which lessens emotions of frustration and overwhelm. Students can more readily comprehend and finish the assignment by concentrating on one step at a time. Task analysis also encourages independence and self-confidence, allowing pupils to complete more tasks independently.

Task analysis can be utilized in various educational contexts, including academic tasks like writing a paragraph or solving a math problem, social skills like making eye contact or asking for help, and self-care chores like taking care of oneself (dressing or preparing a meal). In many cases, teachers may use task boxes for special education to facilitate this learning.

Overall, task analysis is a useful tool for special education instructors and caregivers to assist students to develop their skills and succeed in all facets of life. It aligns with the principles of Universal Design for Learning , which emphasize the customization of teaching to individual learning needs.

Importance of Task Analysis in Education

Task analysis is an essential tool for teachers and students since it enables pupils to divide difficult activities into smaller, easier-to-manage parts. Several factors make task analysis crucial in education, including the following:

- Reduces Overwhelming and Frustration: Complex tasks frequently feel overwhelming and stressful for kids with learning disabilities. These tasks are broken down into smaller, more manageable parts using task analysis, which lessens these sentiments and enables pupils to concentrate on one step at a time.

- Enhances Understanding: By breaking down a task into its parts, pupils can better comprehend what is expected. An improvement in confidence and motivation might result from this understanding.

- Enhances Independence: Students’ self-esteem is raised, and independence is encouraged when they can perform activities alone. Students can develop the abilities they need to succeed by using task analysis. According to the American Psychological Association , fostering independence is key to promoting self-confidence and personal growth in students.

- Gives Students a Clear Plan: Students have a clear plan to follow when given a written or visual list of the steps necessary to finish a task. They can use this plan to self-monitor their work and remind them of their progress.

- Task analysis is adaptable and can be changed to fit the needs of each student. To help students more effectively accomplish their goals, educators might modify the steps based on their strengths and shortcomings.

Task analysis is an evidence-based method that has been proven successful in assisting children with learning issues to succeed in addition to these advantages. By utilizing this tool in the classroom, teachers may give their pupils the assistance and direction they require to reach their greatest potential.

How Do You Write a Task Analysis for Special Education?

Several important steps should be considered when drafting a task analysis for special education. Task Analysis steps are as follows:

- Identify the Task: Decide the task you wish to investigate. Depending on the student’s needs, this could be an academic task, a social skill, or a self-care task.

- Break down the work into smaller, easier-to-manage steps once the work has been determined. Consider the steps necessary to finish the work successfully. For instance, the instructions for tying a shoe might say to “take the laces and make an X,” “cross one lace over the other,” “tuck the lace underneath the other,” and other such things.

- After determining the stages, arrange them in the sequence they must be carried out. Make sure that each step is required and builds on the one before it by considering the logical order of the steps.

- Make it Visual: Use images to make the task analysis easier for the student to understand. This can entail listing the processes in writing or using images or a flowchart, or another visual aid to depict the steps.

- Practice with the student while watching them, using the task analysis as a guide. Follow their development and offer advice as required. Consider simplifying a step or offering more assistance if the student struggles.

These stages will help you build a task analysis tailored to the student’s needs and offer a clear strategy for success. Always be patient and adaptable, and modify the task analysis as necessary to meet the needs of each learner.

Click on the link to view an example of writing a task analysis. [Task Analysis in Special Education ppt]

Task Analysis Examples

Here are a few instances of task analysis in education and examples of action in the classroom:

Writing in Paragraph: Writing can be difficult for many pupils, especially those in special education. Task analysis can divide The writing process into simpler, more manageable parts. Choose a topic, brainstorm ideas, make an outline, write a draft, rewrite and edit, and proofread, for instance, could be the processes in writing a paragraph.

Solving a Math Problem: Some children find math to be a challenging subject. By dividing the problem-solving process into manageable parts, task analysis can assist in making it more approachable. To solve a math problem, for instance, you might follow these steps: read the problem, figure out what you’re solving for, pick a method, solve the problem, and then verify your result.

Developing Social Skills: Task analysis is also beneficial for developing social skills. To develop eye contact, for instance, a student might “stand or sit facing the individual,” “look at their eyes,” “remain to gaze for a few seconds,” “look away briefly,” and “repeat.”

Self-Care Tasks: Special education students could also require assistance with self-care activities like dressing or meal preparation. These jobs can be easier to manage if they are divided into smaller phases through task analysis. For instance, “take off pajamas,” “put on underwear,” “put on pants,” “put on a shirt,” “put on socks,” and “put on shoes” could be the steps to getting dressed.

These are just a few applications of task analysis in the classroom. Task analysis assists in making difficult tasks more approachable and achievable for children with special needs by breaking them down into smaller pieces.

Teach the Task to Autistic Students: Task Analysis Autism Sped Classroom

Task analysis is useful for helping autistic individuals in special education classes. Several instances of task analysis being utilized to assist autistic students are provided below:

- Daily Routines: Routines might be difficult for students with autism. These processes can be divided into smaller, easier-to-manage segments using task analysis. For instance, getting ready for school could involve the following steps: waking up, brushing your teeth, washing your face, dressing, eating breakfast, and packing a backpack.

- Social Skills: Students with autism may also suffer from social skills. Task analysis can simplify these abilities, making them simpler to learn and apply. Making eye contact, smiling, saying hello, asking questions, and paying attention to the answer are some examples of conversation starters.

- Classroom Assignments: Task analysis can help students with autism complete assignments in the classroom, such as worksheets or projects. To finish a worksheet, for instance, you might follow these steps: “Read the directions,” “Look at the example,” “Do the first problem,” “Check the solution,” and “Complete the rest of the problems.”

- Lifestyle Skills: Students with autism could also require assistance with everyday tasks like cooking or laundry. These jobs can be simplified by task analysis into more manageable chunks. For instance, “take out the bread,” “take out the meat,” “take out the cheese,” “place the bread together,” and “cut the sandwich in half” could be the stages of assembling a sandwich.

Task analysis is a flexible approach that may be applied in various ways to support autistic individuals in special education classrooms. Students with autism can develop their talents and succeed in a way that suits their particular requirements by breaking complex tasks into smaller, more manageable steps. I hope you learned and enjoyed our discussion on What Is Task Analysis in Special Education.

Jennifer Hanson is a dedicated and seasoned writer specializing in the field of special education. With a passion for advocating for the rights and needs of children with diverse learning abilities, Jennifer uses her pen to educate, inspire, and empower both educators and parents alike.

Related Posts

Most Restrictive Environment (6 Types in Special Education)

Embracing the Least Restrictive Environment (LRE) Principle in Special Education

The Radiant Spectrum

Task Analysis in Special Education: How to Deconstruct a Task

- September 15, 2022 April 11, 2024

As educators, we often go through the process of deconstructing a task by breaking down a complex skill into smaller steps so that students are able to learn the skill gradually, and easily. This process is known as Task Analysis and is especially crucial when teaching students with special needs.

We typically learn in two ways, explicitly and implicitly. Explicit learning is the intentional experience of acquiring a skill or knowledge, while implicit learning is the process of learning without conscious and deliberate awareness, such as learning how to talk and eat. Our students with special needs benefit more from explicit teaching and learning because they often face challenges acquiring skills implicitly due to the need for contextual understanding, communication skills, and so on.

For explicit teaching and learning to be effective, it is important to have a thorough understanding of the skill through task analysis.

Task Analysis involves a series of thought processes:

1. Goal Selection: Know exactly what it is that you want to teach

Be clear and specific about the goal or the skill that you want to teach. Avoid having too many sub-goals.

- Negative example: Play a complete song.

- Positive example: Press keys on the piano by following the alphabets shown on a flashcard or music score.

2. Identify any prerequisite skills, if any

In our earlier example of teaching the sequence of piano keys, some of the prerequisite skills will include:

- Literacy skills of alphabets and/or colours

- Matching skills of alphabets and/or colours

- Visual referencing skills in top-down and/or left-right motion

- Motor skill of only using one finger to press the key, or to imitate an action

Prerequisite skills are important because these skills help to make the learning more feasible and increase the possibility of successfully performing the new skill.

3. Write a list of all the steps needed to complete the skill you want to teach

A skill can be completed in a single step, or in a series of sequential steps. It is thus helpful that we list down all the steps needed to complete the skill we want to teach. With this, the Task Analysis becomes more detailed and effective. Let’s take the above goal and list down the steps needed.

Goal: Press keys on the piano by following the alphabets shown on a flashcard or music score.

The keys steps needed to complete this task are:

- Look up at the flashed alphabet.

- Process and retain the information in the learner’s working memory.

- Look down at the piano keys.

- Find the corresponding key by scanning past non-target keys.

- Identify and stop at the target key.

- Aim and press with one finger.

4. Identify which steps your child can do and which he/she cannot yet do

The next step will be to know the current skill level of your learner by identifying which steps the learner can do, and which the learner cannot. Assume the learner has the following challenges:

- Not consistent in visual referencing skill of looking up and down repeatedly.

- Unable to focus and scan more than 4 keys at one time.

- Often mistakes Letter G for C and vice versa.

This means that this learner will have challenges in completing Steps 3, 4, and 5 in the above Task Analysis.

5. Isolate any gap skills, if needed, and teach them first

The steps in which the learner cannot do or has challenges in are known as gap skills . After identifying the gap skills, take time to isolate the skills, teach them, and bridge them. This process takes time. For example, looking at the gap skills in the above example:

- Visual Referencing Skill:

This is an abstract skill that takes time to build. It is unlikely that the learner can learn and master this in a couple of weeks. Therefore, to bridge this, the teacher should intentionally provide opportunities for top-down visual referencing across activities and settings, such as taking a toy from a shelf above and keeping them back on top, or sorting activities whereby one item is on top, and one is at the bottom.

- Working Memory Stamina

This is also another skill that takes time to build. Teaching it across settings and activities will be more effective and efficient.

This is a skill that can be taught together with the target skill. Since the learner mistakes G for C and vice versa, and is unable to scan more than 4 keys at any one time, reduce the sequencing to CDEF or FGAB such that there is only either C or G in the target sequence. Once the learner is more confident, isolate C and G so that the learner learns to differentiate the two before the full sequence is introduced again.

Once the gap skills are bridged, the likelihood of the learner performing the target skill will increase vastly.

6. Determine the strategy to be used when completing the target skill, with or without gap skills

At this stage, the learner might still have some gap skills to work on, but the teacher decides to move on to teaching the actual target skill. There are generally three strategies to use:

- Backward Chaining

As the name suggests, Backward Chaining involves the teacher helping the student complete all the steps in the front, leaving only the last step for the learner to do. This also means that the teacher focuses on the last step in the teaching process. The teacher then slowly moves to teach the step before the last until the learner is able to complete all the steps.

- Forward Chaining

This is the opposite of Backward Chaining. The teacher starts teaching from the first step and then moves on chronologically.

- Total Chaining

This strategy involves the learner in all the steps and the teacher teaches all the steps to the learner with prompts. The learner is learning all the steps.

It is common to have tried all three strategies before the teacher is able to decide which one works best, so do not be afraid to evaluate and change your mind halfway!

7. Develop a systematic teaching plan, implement, assess and evaluate the progress

After you decide on your teaching strategy, you can then plan and start the actual teaching. Do remember to assess and evaluate the learner’s progress regularly so as to make the learning effective!

Task Analysis may be a long and daunting process at the beginning. However, the more you do it, the better you get at it. In fact, we are practising the steps of Task Analysis as we write this article for you! Practice more and you will soon see how useful it is.

Interested in more tips on teaching to children with special needs? You can read about the importance and features of a good classroom set-up here !

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

- Skip to Content

- Skip to Main Navigation

- Skip to Search

Indiana University Bloomington Indiana University Bloomington IU Bloomington

- Getting to IRCA

- What to Do If You Suspect Autism

- Learn the Signs. Act Early

- How and Where to Obtain a Diagnosis/Assessment

- After the Diagnosis: A Resource for Families Whose Child is Newly Diagnosed

- For Adolescents and Adults: After You Receive the Diagnosis of an Autism Spectrum Disorder

- Introducing Your Child to the Diagnosis of Autism

- Diagnostic Criteria for Autism Spectrum Disorder

- Diagnostic Criteria for Social (Pragmatic) Communication Disorder

- Indiana Autism Spectrum Disorder Needs Assessment

- Online Offerings

- Training and Coaching

- Individual Consultations

- School District Support

- Reporter E-Newsletter

- Applied Behavior Analysis

- Communication

- Educational Programming

- General Information

- Mental Health

- Self Help and Medical

- Social and Leisure

- Articles Written by Adria Nassim

- Articles by Temple Grandin

- Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA)

- Early Intervention

- Self-Help and Medical

- IRCA Short Clips

- Work Systems: Examples from TEACCH® Training

- Structured Tasks: Examples from TEACCH® Training

- Schedules: Examples from TEACCH® Training

- Holidays and Celebrations

- Health and Personal Care

- Behavior and Emotions

- Family Early Intervention Resource Cards

- Financial Resources

- State Resources

- Materials Request

- Comprehensive Programming for Students Across the Autism Spectrum Training

- Paraprofessional Training Modules

- Family Support Webinars

- Workshops with Dr. Brenda Smith Myles

- Workshops with Dr. Kathleen Quill

- First Responder Training

- IRCA Briefs

Indiana Institute on Disability and Community

Indiana Resource Center for Autism

Applied behavior analysis: the role of task analysis and chaining.

By: Dr. Cathy Pratt, BCBA-D, Director, Indiana Resource Center for Autism and Lisa Steward, MA, BCBA, Director, Indiana Behavior Analysis Academy

A task analysis is used to break complex tasks into a sequence of smaller steps or actions. For some individuals on the autism spectrum, even simple tasks can present complex challenges. Having an understanding of all the steps involved for a particular task can assist in identifying any steps that may need extra instruction and will help teach the task in a logical progression. A task analysis is developed using one of four methods. First, competent individuals who have demonstrated expertise can be observed and steps documented. A second method is to consult experts or professional organizations with this expertise in validating the steps of a required task. The third method involves those who are teaching the skill to perform the task themselves and document steps. This may lead to a greater understanding of all steps involved. The final approach is simply trial and error in which an initial task analysis is generated and then refined through field tests (Cooper, Heron, Howard, 2020).

As task analyses are developed, it is important to remember the skill level of the person, the age, communication and processing abilities, and prior experiences in performing the task. When considering these factors, task analyses may need to be individualized. For those on the autism spectrum, also remember their tendency toward literal interpretation of language. For example, students who have been told to put the peanut butter on the bread when making a peanut butter and jelly sandwich have literally just placed the entire jar on the bread. It is important that all steps are operationally defined. Below are two examples of task analyses.

Putting a Coat On

- Pick up the coat by the collar (the inside of the coat should be facing you)

- Place your right arm in the right sleeve hole

- Push your arm through until you can see your hand at the other end

- Reach behind with your left hand

- Place your arm in the left sleeve hole

- Move your arm through until you see your hand at the other end

- Pull the coat together in the front

- Zip the coat

Washing Hands

- Turn on right faucet

- Turn on left faucet

- Place hands under water

- Dispense soap

- Rub palms to count of 5

- Rub back of left hand to count of 5

- Rub back of right hand to count of 5

- Turn off water

- Take paper towel

- Dry hands to count of 5

- Throw paper towel away

Skills taught using a task analysis (TA) include daily living skills such as brushing teeth, bathing, dressing, making a meal, and performing a variety of household chores. Task analysis can also be used in teaching students to perform tasks at school such as eating in the cafeteria, morning routines, completing and turning in assignments, and other tasks. Task analysis is also useful in desensitization programs such as tolerating haircuts, having teeth cleaned, and tolerating buzzers or loud environments. Remember that tasks we perceive as simple may be complex for those on the spectrum.

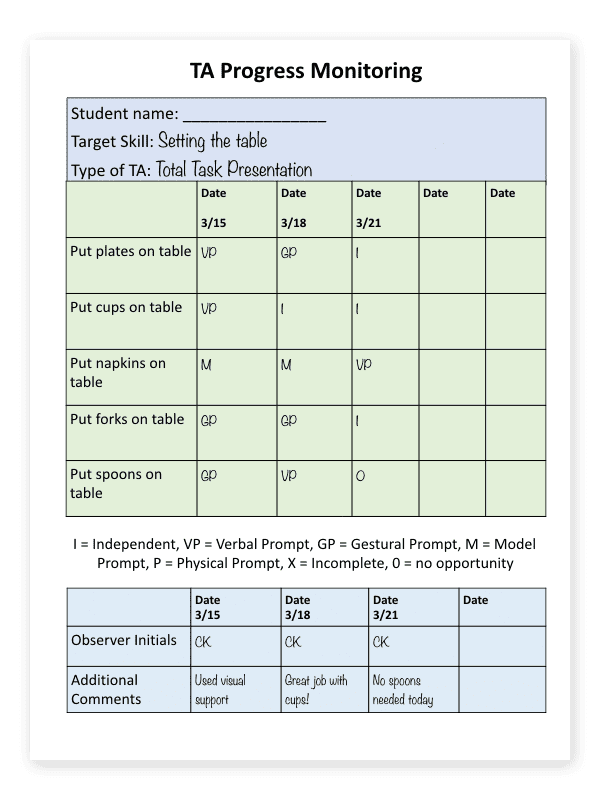

Again, the number of steps involved and the wording used will differ dependent on the individual. Determining the steps to a TA as well as the starting point for an individual often requires collecting baseline data, and/or examining the individual’s ability to complete any or all of the required steps. Assessing the individual’s level of mastery can occur in one of two ways. Single-opportunity data involves collecting information on each step correctly performed in the task analysis. Once a mistake is made, data collection stops and no further steps are examined. In multiple opportunity data collection, progress is documented on each step regardless of whether the performance was correct or not. This provides insight into those steps the student can perform and where additional training or support is needed. Remember that once implementation begins, the TA may need to be revised to address any additional needs.

Once a task analysis is developed, chaining procedures are used to teach the task. Forward chaining involves teaching the sequence beginning with the first step. Typically, the learner does not move onto the second step until the first step is mastered. In backward chaining, the sequence is taught beginning with the last step. And again, the previous step is not taught until the final step is learned. One final strategy is total task teaching. Using this strategy, the entire skill is taught and support is provided or accommodations made for steps that are problematic. Each of these strategies has benefits. In forward chaining, the individual learns the logical sequence of a task from beginning to end. In backward chaining, the individual immediately understands the benefit of performing the task. In total task training, the individual is able to learn the entire routine without interruptions. In addition, they are able to independently complete any steps that have been previously mastered.

Regardless of the strategy chosen, data has to be collected to document successful completion of the entire routine and progress on individual steps. How an individual progresses through the steps of the task analysis and what strategies are used have to be determined via data collection.

Cooper, J.O., Heron, T.E, and Heward, W.L. (2020). Applied behavior analysis (3rd Edition). Pearson Education, Inc.

Pratt, C. & Steward, L. (2020). Applied behavior analysis: The role of task analysis and chaining. https://www.iidc.indiana.edu/irca/articles/applied-behavior-analysis.html .

2810 E Discovery Parkway Bloomington IN 47408 812-856-4722 812-855-9630 (fax) Sitemap

Director: Rebecca S. Martínez, Ph.D., HSPP

Sign Up for Our Newsletter

The IRCA Reporter is filled with useful information for individuals, families and professionals.

About the Center

One Step at a Time: Using Task Analyses to Teach Skills

- Published: 03 February 2017

- Volume 45 , pages 855–862, ( 2017 )

Cite this article

- Melinda R. Snodgrass 1 ,

- Hedda Meadan 2 ,

- Michaelene M. Ostrosky 2 &

- W. Catherine Cheung 2

2947 Accesses

6 Citations

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Task analyses are useful when teaching children how to complete tasks by breaking the tasks into small steps, particularly when children struggle to learn a skill during typical classroom instruction. We describe how to create a task analysis by identifying the steps a child needs to independently perform the task, how to assess what steps a child is able to do without adult support, and then decide how to teach the steps the child still needs to learn. Using task analyses can be the key to helping a young child become more independent.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Conducting Task Analysis

A Framework for Teachable Collaborative Problem Solving Skills

Introduction to the Special Section: Precision Teaching: Discoveries and Applications

Explore related subjects.

- Artificial Intelligence

Alberto, P. A., & Troutman, A. C. (2013). Applied behavior analysis for teachers (9th edn.). Upper Saddle River: Pearson.

Google Scholar

Allen, K. E., & Cowdery, G. E. (2015). The exceptional child: Inclusion in early childhood education (8th edn.). Stamford: Cengage Learning.

Ault, M. J., & Griffen, A. K. (2013). Teaching with system of least prompts: An easy method for monitoring progress. Teaching Exceptional Children, 45 , 46–53.

Article Google Scholar

Baumgart, D., Brown, L., Pumpian, I., Nisbet, J., Ford, A., Sweet, M., Messina, R., & Schroeder, J. (1982). Principle of partial participation and individualized adaptations in educational programs for severely handicapped students. Journal of the Association for People with Severe Handicaps, 7 , 17–27.

Bijou, S. W., & Sturges, P. T. (1959). Positive reinforcers for experimental studies with children—Consumables and manipulatables. Child Development, 30 , 151–170. doi: 10.2307/1126138 .

Burns, M. K., & Ysseldyke, J. E. (2009). Reported prevalence of evidence-based instructional practices in special education. Journal of Special Education, 43 , 3–11. doi: 10.1177/0022466908315563 .

Catalino, T., & Meyer, L. E. (Eds.) (2016). Environment: Promoting meaningful access participation, and inclusion (DEC Recommended Practices Monograph Series No. 2) . Washington, DC: Division for Early Childhood.

Cook, B. G., & Odom, S. L. (2013). Evidence-based practices and implementation science in special education. Exceptional Children, 79 , 135–144.

Copple, C., Bredekamp, S., Koralek, D., & Charner, K. (Eds.). (2014). Developmentally appropriate practice: Focus on kindergartners . Washington, DC: NAEYC.

Dammann, J. E., & Vaughn, S. (2001). Science and sanity in special education. Behavioral Disorders, 27 , 21–29.

Division of Early Childhood. (2015). DEC recommended practices: Enhancing services for young children with disabilities and their families (DEC Recommended Practices Monograph Series No. 1) . Los Angeles, CA: Division of Early Childhood.

Every Student Succeeds Act of 2015, S.1177, 114th Cong. (2015). Retrieved from http://www2.ed.gov/documents/essa-act-of-1965.pdf .

Gargiulo, R. M., & Kilgo, J. L. (2011). An introduction to young children with special needs (3rd edn.). Belmont: Wadsworth.

Graves, S. (1990). Early childhood education. In T. E. C. Smith (Ed.), Introduction to education (2nd edn., pp. 189–219). St. Paul: West.

Holfester, C. (2008). The Montessori method [topic overview]. Retrieved from http://www.williamsburgmontessori.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/08/The_Montessori_ Method.pdf .

Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act (IDEA) of 2004, 20 U.S.C. §§1400 et sEq . (2004) (reauthorization of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act).

International Montessori Index. (2006). Maria Montessori [webpage]. Retrieved from http://www.montessori.edu .

Meadan, H., Ostrosky, M. M., Santos, R. M., & Snodgrass, M. R. (2013). How can I help? Prompting procedures to support children’s learning. Young Exceptional Children, 16 (4), 31–39. doi: 10.1177/1096250613505099 .

Moyer, J. R., & Dardig, J. C. (1978). Practical task analysis for special educators. TEACHING Exceptional Children, 11 , 16–18.

Odom, S. L., Collett-Klingenberg, L., Rogers, S. L., & Hatton, D. D. (2010). Evidence-based practices in interventions with children and youth with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Preventing School Failure, 54 , 275–282. doi: 10.1080/10459881003785506 .

Snell, M. E., & Brown, F. (2011). Selecting teaching strategies and arranging educational environments. In M. E. Snell & F. Brown (Eds.), Instruction of students with severe disabilities (7th edn., pp. 122–185). Upper Saddle River: Pearson.

Stokes, T. F., & Baer, D. M. (1977). An implicit technology of generalization. Journal of Applied Bheavior Analysis, 10 , 349–367.

United Nations. (2006). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities , Article 24. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/disabilities/convention/conventionfull.shtml .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Special Education, Hunter College, City University of New York, 695 Park Ave, Room W929, New York, NY, 10065, USA

Melinda R. Snodgrass

Department of Special Education, University of Illinois, Champaign, USA

Hedda Meadan, Michaelene M. Ostrosky & W. Catherine Cheung

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Melinda R. Snodgrass .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Snodgrass, M.R., Meadan, H., Ostrosky, M.M. et al. One Step at a Time: Using Task Analyses to Teach Skills. Early Childhood Educ J 45 , 855–862 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-017-0838-x

Download citation

Published : 03 February 2017

Issue Date : November 2017

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-017-0838-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Evidence-based practice

- Functional skills

- Young children

- Disabilities and developmental delays

- Natural environment

- Independence

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Special Educator Academy

Free resources, what you need to know about task analysis and why you should use it.

Sharing is caring!

Returning to the Effective Interventions in Applied Behavior Analysis series , I wanted to talk a little about the use of task analysis and why it’s important. For more information on how we use task analyses, check out this post on using shaping and this one on using chaining .

Everyone in special education has probably heard about task analysis. It’s a decidedly unexciting topic in some ways, but it so critical to systematic instruction that we have to address it. In addition, there is a lot of misinformation flying around out there so hopefully this will address just what you need to know about them.

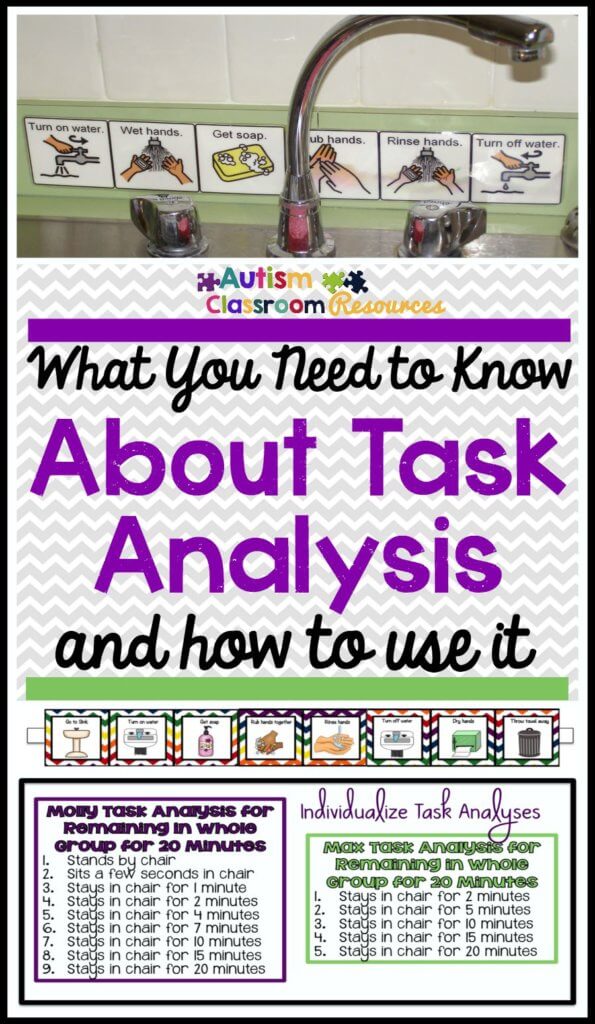

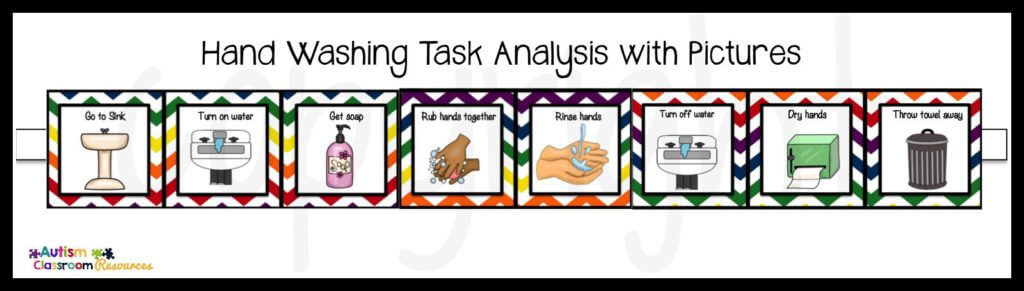

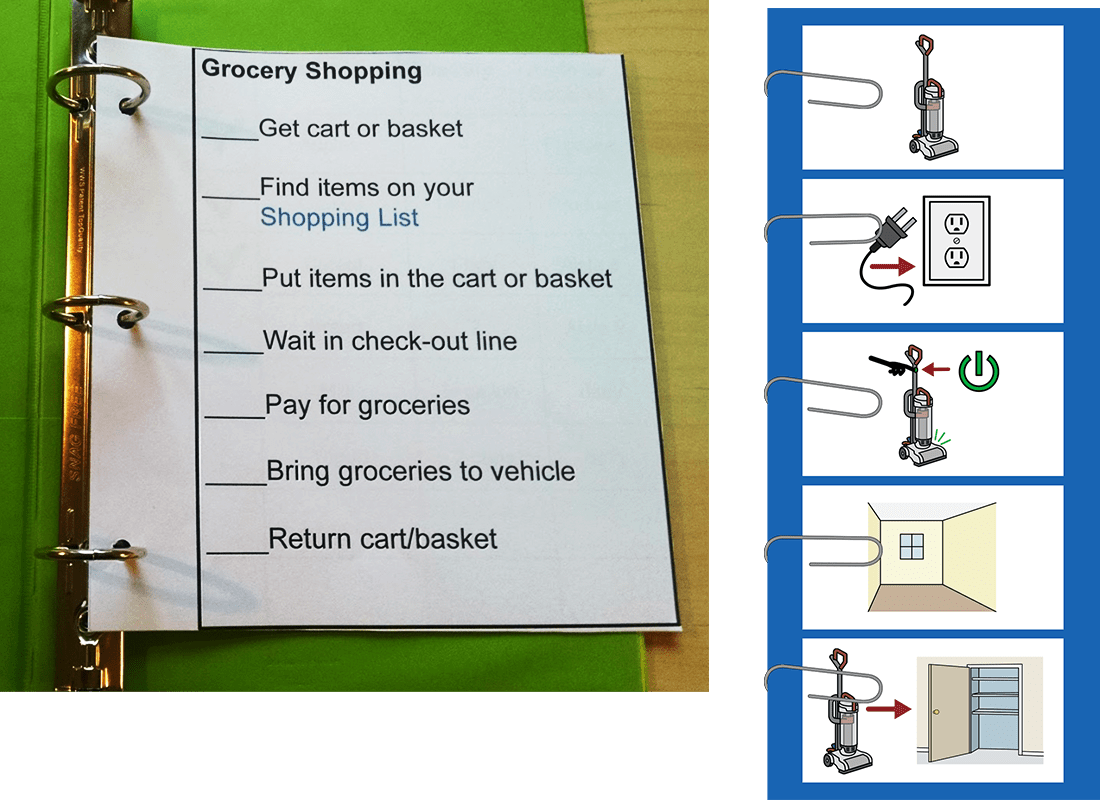

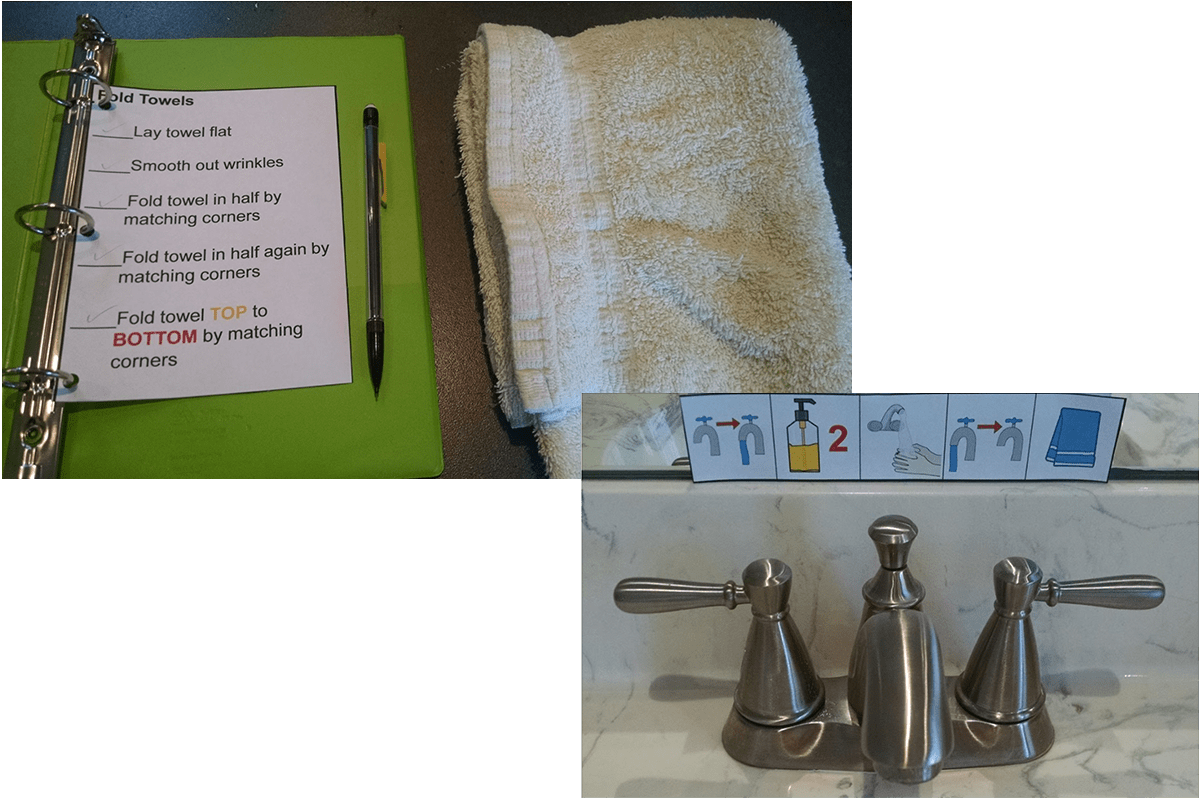

We are told to use them frequently in the classroom to break skills down into smaller components. So, we set up steps, like we do for some of our mini-schedules like the one below for washing hands . Sometimes task analyses have visuals to support them and sometimes they are just written out for the staff.

What is a task analysis?

So if you aren’t familiar with the jargon, what does task analysis mean? The National Professional Development Center found task analysis to be an evidence-based practice, which interests me because I don’t think that behavioral task analysis is actually an intervention. I see the task analysis process as part of other interventions. A task analysis is simply a set of steps that need to be completed to reach a specific goals. There are basically two different ways to break down a skill. You can break it down by the steps in a sequence to complete the task. The hand washing task analysis does that. In this type of task analysis you have to complete one step to be ready for the next. For instance, you have to turn on the water to get your hands wet. This type of task analysis is typically used with chaining which will be the topic of our next post.

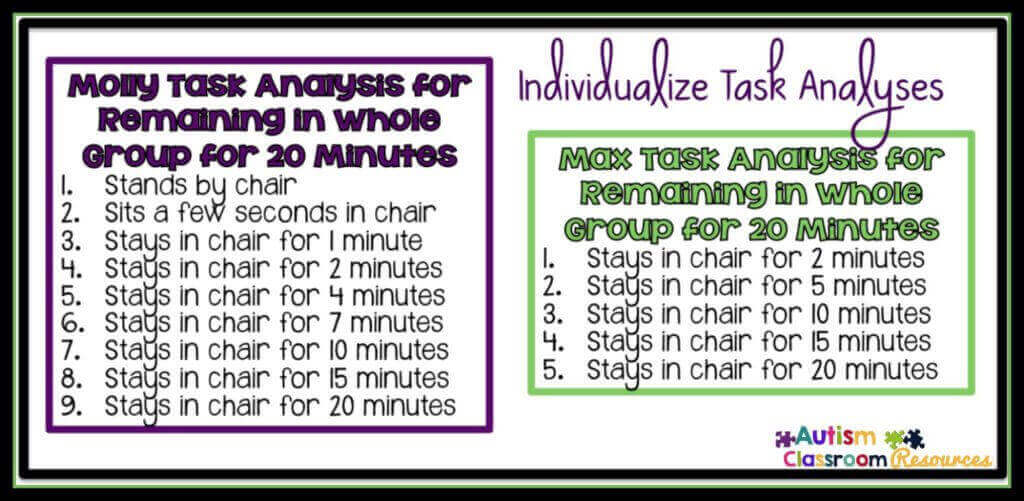

You can also have a task analysis that breaks skills down into smaller chunks, like increasing time. A task analysis for remaining in a group might do that like the examples at the bottom of the picture above. In this type of task analysis, each step replaces the one that comes before it. So, when you sit for 5 minutes, that includes all the steps that come before. This type of task analysis is usually used with shaping, which I will talk about in 2 weeks.

Why Do I Need a Task Analysis?

So if a task analysis is just breaking skills down into smaller skills, you probably do it all the time. Conducting a task analysis isn’t a very time-consuming process.

But, why is using a specific task analysis that is established for a student important? Below are 3 reasons to answer that question.

1. Consistency

In order to assure that everyone is teaching a skill in the same way, breaking it down into the same steps is critical. I am willing to bet that if you ask parents, paraprofessionals or even your significant other how they brush their teeth, you will find some variation in the order of the steps. Your significant other doesn’t put the cap back on the toothpaste. You keep the water running while you brush your teeth while your paraprofessional turns it off to conserve water until she is ready to rinse. My point is that we all have individual differences in the steps of completing simple, everyday tasks. Now, imagine that you are a student who is having difficulty learning to brush his teeth. If you show me one way and prompt me through the steps, and then the parapro shows me another way and prompts me through her steps, and my mom shows me a third way, I’m going to be pretty confused. It’s the beginning of the year and we all need a laugh, so here’s a great video example of why it’s important. Archie and Michael can’t even agree on how to put on shoes and socks. Imagine if they both tried to teach one of our students to put theirs on (no, I would not recommend doing this)–how confused would that student be?

Take Away Point: Writing down a task analysis assures that everyone follows the same steps and teaches the student the same way. Then your instruction is much less confusing and more efficient. 2. Tailor It To The Student

Students need task analyses that are tailored to their needs. I love starting with standard ones, so I don’t have to reinvent the wheel, but then adjusting them to meet the needs of this student. Here’s why the individualization is so important. If your steps are too large for the student, he or she may not make it to the next step and will stall out. For instance, if you are teaching Molly to stay in a group activity for 20 minutes and your task analysis jumps from 5 minutes (that she can currently stay) to 10 minutes, she might never be successful at jumping to 10 minutes and won’t progress. She might do better if we went to 7 minutes next and then 9 minutes. On the other hand, for Max, if we were teaching the same skill and we had him stay in the group for 5 minutes, then 7 minutes and then 9 minutes it might take a very long time when he could have made the jump straight to 10 minutes. Each student is different and we have to figure out how to individualize their steps based on their past data. Is it taking too long to master a step? Step it down to a smaller step. Is he mastering steps really quickly? Make the steps bigger.

3. It is the Basis for Systematic Instruction

Breaking skills down is a critical component of discrete trial programming as well as teaching life skills and other chaining and shaping applications. Discrete trial programs are made up of smaller steps that lead to a larger goal. Learn 1 letter, then 2, then 3? That’s a shaping task analysis. Our research shows us that it’s important to break skills down for students with autism in order to eliminate extraneous variables that might mess up their learning. Teaching systematically is the key to success with any student and especially any student in special education. It’s also key for some of our students to be able to show progress. While it’s not exciting to say that a student has mastered 4 of the 8 steps of tying his shoes, it better than being able to say AGAIN that he can’t tie his shoes–assuming he had no steps mastered earlier in the year. It’s slow progress, but it’s progress.

So, how do you use task analyses in your classroom and why do you think they are important? Are there questions you have about task analyses or teaching strategies that use them? Please share them in the comments and I will try to address them. In the meantime, I’ll be back next Thursday to talk about ways to make your instruction using task analyses more efficient.

- Read more about: Curriculum & Instructional Activities , Effective Interventions in ABA

You might also like...

![methods of task analysis in special education Summer resources to help survive the end of the year in special education [picture-interactive books with summer themes]](https://autismclassroomresources.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/SUMMER-RESOURCES-ROUNDUP-FEATURE-8528-768x768.jpg)

Summer Resources That Will Help You Survive the End of the Year

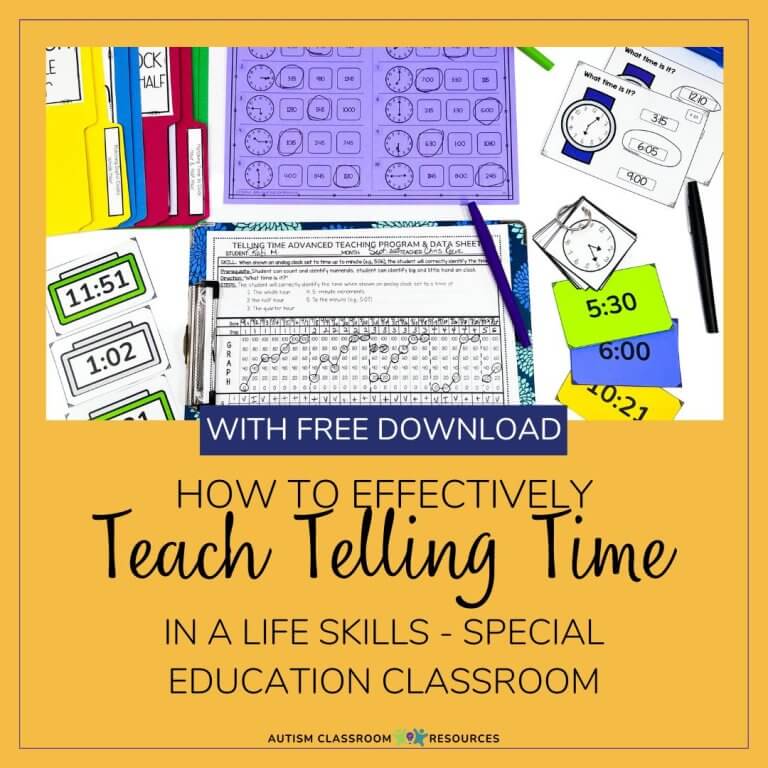

How to Effectively and Efficiently Teach Telling Time: Hands-On Learning in Action for Special Education

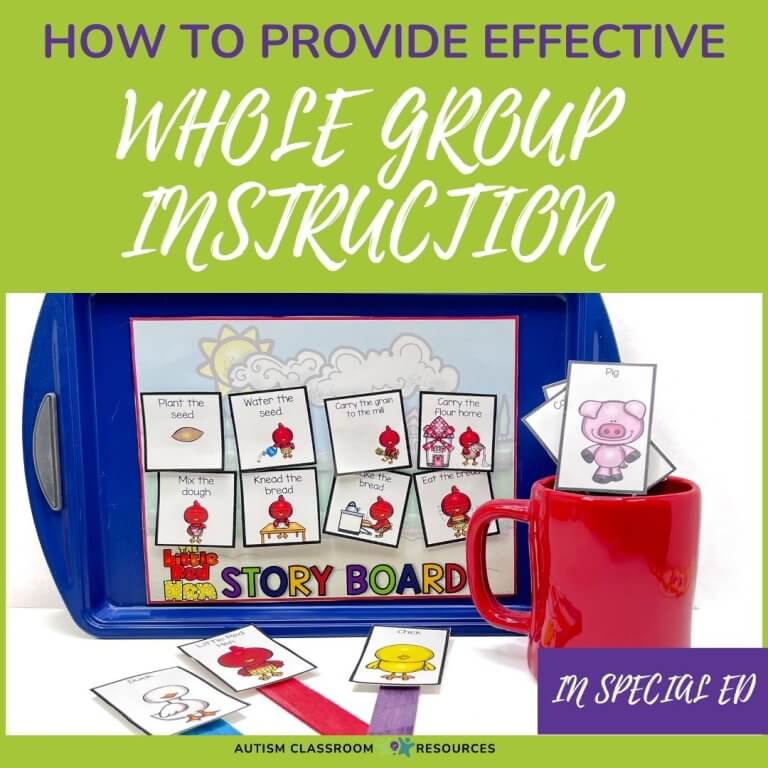

How To Provide Effective Whole Group Instruction in Special Education?

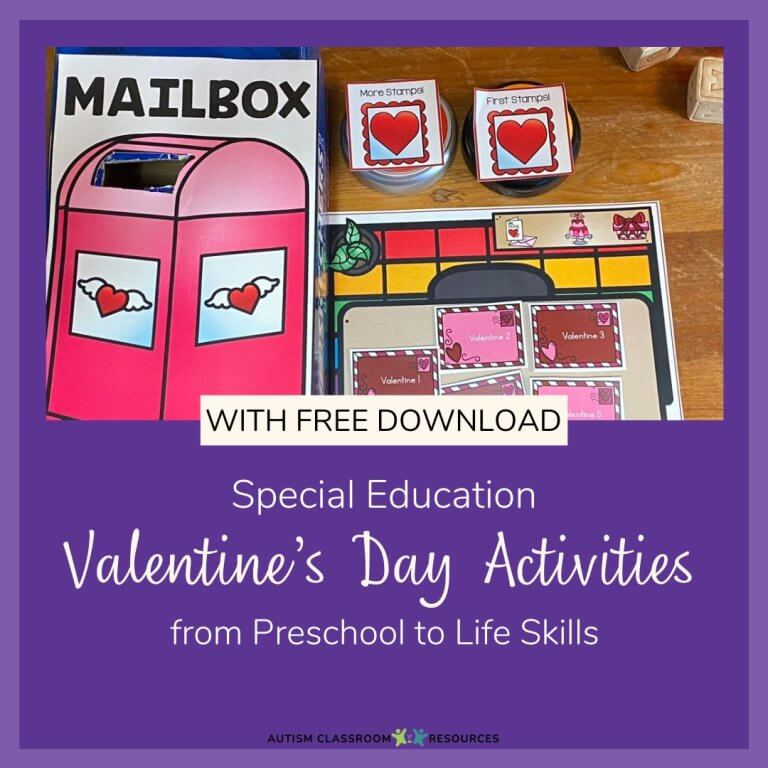

Valentines Day Activities for Special Education from Preschool to Life Skills-Free Download

Grab a free resource.

(and get free tips by email)

Training & Professional Development

- On-Site Training

- Virtual Training

Privacy Policy

Disclosures and copyright.

- Core Beliefs

Unlock Unlimited Access to Our FREE Resource Library!

Welcome to an exclusive collection designed just for you!

Our library is packed with carefully curated printable resources and videos tailored to make your journey as a special educator or homeschooling family smoother and more productive.

Loading to Examples Of Task Analysis In Special Education....

Techniques for Teaching Complex Skills to Children with Special Needs

By: The RethinkEd Team

- • Special Education , Tips, Tools, & Tech

Have you ever written a shopping list for the upcoming weeks groceries and then forgot to bring it with you to the store? If so, you will know how difficult it is to remember everything that was on the list. The same is true when we have to remember significant amounts of information for an exam or a test.

For children with special needs; remembering all of the steps to a skill such as washing their hands or following a daily schedule can be a similar challenge.

The good news is that there is an evidence-based tool called a “task analysis” that we can use to break any complex tasks into a sequence of smaller steps or actions to help our children learn and become more independent.

What is a Task Analysis?

Task analyses can take on many forms depending on how your child learns.

The examples below show written lists for how to complete tooth brushing:

If you are working with children who can read and understand directions, you can use a task analysis that has a lot of detail, such as this example for doing laundry.

If your child is unable to read, task analyses can be made using just picture cards or actual photographs to illustrate the steps of a skill. These examples following a morning routine, riding in the car and using a stapler:

How do I create a Task Analysis?

Here are the steps to take to create a task analysis to help your child:

- Physically complete all of the steps of the skill yourself

- Do the skill again and write down each step as you do it

- Compile all the steps into a sequence using words, pictures or both that your child will be able to understand and use to help them learn

There is no set number of steps to a skill. Some children will require the skill broken down into many small steps to be able to be successful, others may require less steps. You can decide how many steps will be needed for your child to learn.

How do I know if my child is learning?

You can observe your child to see if they are making progress, however having a little bit of data will show you exactly how fast your child is progressing and which steps are being mastered, as well as which steps may need more learning attention. To take data, you would note if the child completed each step correctly (independently) or incorrectly (needed help). Here is an example for a simple data collection sheet for getting dressed:

| Date: March 3rd | Describe Step | Did the child complete independently? (Yes or No) |

| Step 1 | Take off PJ’s | Yes |

| Step 2 | Put on underwear | Yes |

| Step 3 | Put on pants | Yes |

| Step 4 | Put on shirt | No |

| Step 5 | Put on socks | No |

| Step 6 | Put on shoes | No |

Resources of Task Analysis for Special Needs Children

For more resources and information about using a task analysis:

The tools every district needs to design, deliver and monitor evidence-based practices in special education. (2015). Retrieved March 10, 2017, from RethinkFirst https://www.rethinkfirst.com/

Developing Life Skills: How to Teach A Skill. (n.d.). Retrieved March 10, 2017, from TACA , https://tacanow.org/family-resources/life-skills/

Printable Picture Cards. (n.d.). Retrieved March 10, 2017, from Do2Learn , https://do2learn.com/picturecards/printcards/index.htm

Says, R., Says, C., Says, J., & Says, D. W. (2015, August 27). What You Need to Know About Task Analysis and Why You Should Use It. Retrieved March 10, 2017, from Autism Classroom Resources , https://autismclassroomresources.com/what-you-need-to-know-about-task-analysis-and-why-you-should-use-it/

Share with your community

Sign up for our Newsletter

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter on the latest industry updates, Rethink happenings, and resources galore.

Related Resources

Running on Empty: Teachers Are Not Prepared for Increasing Challenging Behaviors

Preventing School Violence: Building a Safer Future

Parent and Caregiver Involvement: A Critical Component to Student Outcomes

Join our newsletter and stay up to date on features and releases.

©2024 Rethink. All rights reserved.

49 W 27th St, 8th floor, New York, NY 10001

We Use Cookies

Privacy overview.

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| __hssrc | session | This cookie is set by Hubspot whenever it changes the session cookie. The __hssrc cookie set to 1 indicates that the user has restarted the browser, and if the cookie does not exist, it is assumed to be a new session. |

| __lc_cid | 2 years | This is an essential cookie for the website live chat box to function properly. |

| __lc_cst | 2 years | This cookie is used for the website live chat box to function properly. |

| __oauth_redirect_detector | past | This cookie is used to recognize the visitors using live chat at different times inorder to optimize the chat-box functionality. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-advertisement | 1 year | Set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin, this cookie is used to record the user consent for the cookies in the "Advertisement" category . |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 1 year | Set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin, this cookie is used to record the user consent for the cookies in the "Analytics" category . |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 1 year | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 1 year | Set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin, this cookie is used to record the user consent for the cookies in the "Necessary" category . |

| elementor | never | This cookie is used by the website's WordPress theme. It allows the website owner to implement or change the website's content in real-time. |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 1 year | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin to store whether or not the user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| __hstc | 5 months 27 days | This is the main cookie set by Hubspot, for tracking visitors. It contains the domain, initial timestamp (first visit), last timestamp (last visit), current timestamp (this visit), and session number (increments for each subsequent session). |

| _ga | 2 years | The _ga cookie, installed by Google Analytics, calculates visitor, session and campaign data and also keeps track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookie stores information anonymously and assigns a randomly generated number to recognize unique visitors. |

| _gat_UA-101741318-1 | 1 minute | A variation of the _gat cookie set by Google Analytics and Google Tag Manager to allow website owners to track visitor behaviour and measure site performance. The pattern element in the name contains the unique identity number of the account or website it relates to. |

| _gcl_au | 3 months | Provided by Google Tag Manager to experiment advertisement efficiency of websites using their services. |

| _gid | 1 day | Installed by Google Analytics, _gid cookie stores information on how visitors use a website, while also creating an analytics report of the website's performance. Some of the data that are collected include the number of visitors, their source, and the pages they visit anonymously. |

| CONSENT | 2 years | YouTube sets this cookie via embedded youtube-videos and registers anonymous statistical data. |

| hubspotutk | 5 months 27 days | HubSpot sets this cookie to keep track of the visitors to the website. This cookie is passed to HubSpot on form submission and used when deduplicating contacts. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| CONSISTENCY | YouTube | |

| GPS | YouTube | |

| IDE | 1 year 24 days | Google DoubleClick IDE cookies are used to store information about how the user uses the website to present them with relevant ads and according to the user profile. |

| PREF | session | YouTube, store user preferences |

| test_cookie | 15 minutes | The test_cookie is set by doubleclick.net and is used to determine if the user's browser supports cookies. |

| VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE | 6 months | YouTube |

| YSC | YouTube, store and track interaction. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| __cf_bm | 30 minutes | This cookie, set by Cloudflare, is used to support Cloudflare Bot Management. |

| __hssc | 30 minutes | HubSpot sets this cookie to keep track of sessions and to determine if HubSpot should increment the session number and timestamps in the __hstc cookie. |

| bcookie | 2 years | LinkedIn sets this cookie from LinkedIn share buttons and ad tags to recognize browser ID. |

| bscookie | 2 years | LinkedIn sets this cookie to store performed actions on the website. |

| lang | session | LinkedIn sets this cookie to remember a user's language setting. |

| lidc | 1 day | LinkedIn sets the lidc cookie to facilitate data center selection. |

| UserMatchHistory | 1 month | LinkedIn sets this cookie for LinkedIn Ads ID syncing. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| AnalyticsSyncHistory | 1 month | No description |

| li_gc | 2 years | No description |

- DOI: 10.1177/016264347900200305

- Corpus ID: 62070218

Task Analysis in Special Education: Definition and Clarification

- Ronald W. Schworm

- Published 1 March 1979

- Journal of Special Education Technology

Tables from this paper

3 Citations

Strategies for task analysis in special education, task analysis and the characteristics of tasks, a cumulative author index of the journal of special education technology: 1(1), 1978–9(4), 1989, 12 references, task analysis in curriculum design: a hierarchically sequenced introductory mathematics curriculum., ability training and task analysis in diagnostic/prescriptive teaching, practical task analysis for special educators, task analysis of a complex assembly task by the retarded blind, developmental task analysis and psychoeducational programming., wholes and parts in teaching, beyond behavioral objectives: individualizing learning, training mentally retarded adolescents to brush their teeth., developing programs for severely handicapped students: teacher training and classroom instruction, task analysis: a consideration for teachers of skills, related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

Using Task Analysis to Teach Daily Living Skills

Educational Consultant

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Task analysis is used to break down complex skills into manageable, discrete steps. Students learn the individual steps in sequence in order to master the overall skill. Task analysis can be easy to use as it often requires few materials, can be inexpensive and can be used in a variety of settings. Most importantly, it supports students who have difficulty with executive functioning skills like sequencing, working memory and attention.

Start to think beyond academics and imagine the impact that task analysis can have in supporting your students’ daily living skills. Sequence the steps for hygiene activities like handwashing, toothbrushing or toileting. Provide supports for steps involved in household chores like dusting, cleaning the bedroom, clearing the table or picking up toys. Teach complex tasks in the kitchen like making a sandwich, putting away groceries and setting the table.

Planning for Task Analysis

Have a concrete goal in mind by clearly defining the expected behavior . Rather than simply saying that your student will wash their hands, it is helpful to explicitly state that your student will wash their hands with soap for 20 seconds and dry their hands when finished.

Before teaching the skill, ensure that each individual step is identified and put in the correct sequence. It can be helpful to perform the skill yourself, or observe another adult performing the skill, and record each individual step. For example, to develop a task analysis for washing dishes, start with the step of turning on the water. Complete and record each individual step, being careful not to leave out any detail.

As part of the planning process, take time to observe your student completing the target skill . This will give you a clear idea of what level and types of support to provide for each step of the task. It may also highlight any routines that your student has already developed around this activity as well as reveal areas of strength.

Once you have identified each step and observed your student engaging in the activity, think about how best to present the task analysis to your student. Line drawings or photographs like those in decision trees may be helpful to support some students. A written checklist might be appropriate for others. Even video modeling can be meaningful and appropriate for some students. Consider your student’s level of learning to determine the best presentation.

Tips for Implementing Task Analysis

Forward Chaining

Start by teaching and reinforcing the first step in the chain. Then support your student’s completion of the remaining steps by starting with the least amount of prompting necessary to help your student complete the step successfully. Again, an initial observation of your student’s skill can provide some insight into what level of support is appropriate. Once the first step is mastered (i.e., once your student can independently complete the first step), teach and reinforce the second step while continuing to support the steps that follow.

Backward Chaining

Start by teaching and reinforcing the last step in the chain as you provide a model and support for all steps prior to the last. As the last step is mastered, move backward in the sequence by teaching and reinforcing the second-to-last step. Backward chaining lets your student end every teaching session with success and positive reinforcement.

Total Task Presentation

Present all steps of the sequence at one time. Teach and reinforce each step of the process. This allows your student to learn a complete routine and understand the expectations of the full task from the start.

Task analysis is most effective when paired with a positive reinforcement . As your student performs an individual step or completes the total task (as described above), reinforce their behavior. Consider what reinforcers are motivating and meaningful to your student. This could be verbal praise, a high five or a small token. Keep it simple, and be sure that the selected reinforcer is effective for your student.

In addition to reinforcement, use task analysis in combination with other evidence-based practices. Various levels of prompting can support your student’s learning. Video modeling and visual supports, such as social narratives and decision trees , may also be used to clarify expectations and increase understanding of the skill being taught.

Monitor Your Intervention

Consider the Skill Itself

Has it been clearly defined? Is it truly measurable? Without these characteristics, student progress is difficult to accurately monitor. Also revisit your student’s skill level. Are the prerequisite skills truly present? Is the skill aligned with the IEP and achievable as it is written?

Look Closely at the Task Analysis

Is the skill completely task analyzed? Is there a step missing? Be sure that every step of the sequence is a discrete skill, and not a series of steps collapsed into one.

Review Implementation

If other team members are also teaching this skill, be sure that everyone is using the same chaining method for using task analysis. A thorough task analysis will support consistent implementation as well. Ensure that additional supports (video models, social narratives, visual supports, etc.) are being used in the same way each time.

Reconsider the Positive Reinforcement

If your student is showing a lack of progress, interest or engagement, it may be necessary to find a more effective way to reinforce the skill.

Task analysis can effectively be used to teach daily living skills by breaking down tasks into manageable parts. With thoughtful planning, consistent implementation and careful monitoring, you can support your student’s growth in this area.

About the Author

Becky Dees is an Educational Consultant who specializes in Autism Spectrum Disorder. She has worked as an autism clinician, an educational coach, and a special education trainer. Becky currently works with the autism group in research at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Becky received her degree in psychology from UNC‑Chapel Hill.

You might also like...

What’s New for September

EdXchange Evidence-based Practices in Special Education

What’s new for august.

- Try & Buy

- Get a Quote

- Request a Trial

- Schedule a Demo

- Try some Samples

Select your role to sign in.

If you're signing into a trial, please select Teacher/Admin .

Teacher/Admin

How can we help you.

Ready to try or buy?

Contact Sales

Need product support?

Contact Customer Care

Role Of Task Analysis In Special Education

Task analysis is a powerful teaching strategy that has been proven to be highly effective in special education. By breaking down complex skills and tasks into smaller, more manageable steps, task analysis helps students with special needs to learn and master new skills at their own pace.

This method is not only highly effective but also highly individualized, allowing teachers to tailor their instruction to meet the unique needs of each student. From teaching life skills to improving academic performance, task analysis can be a valuable tool for supporting the development and success of students of all abilities.

In this post, we will explore what is task analysis in special education, its benefits, how to implement it, and some real-world examples to easily comprehend how it has helped students with special needs succeed in the classroom and beyond.

What is task analysis in special education?

Task analysis is often used in special education as a tool for teaching functional skills such as cooking, personal hygiene, and money management. The process involves identifying the steps required to complete a task, teaching each step systematically, and providing ongoing support and feedback until the student can perform the task independently. By breaking down tasks into smaller parts, task analysis makes it easier for students with special needs to learn new skills and develop their independence.

Teaching a new task to a student can be a challenging but rewarding experience for both the educator and the student. To ensure success, it is important to follow a systematic approach that involves clearly identifying and breaking down the task, teaching it using appropriate strategies, providing practice and feedback, and gradually integrating the steps into a complete task.

- Identifying the task: This involves clearly defining the task to be taught, including the specific skills required to complete the task and the goals to be achieved. It is important to identify the task in detail, including the materials and equipment needed, the steps involved, and any potential obstacles that may arise.

- Breaking down the task: The complex task is divided into smaller, more manageable parts or steps. Each step is then described in detail, including the actions required, the sequence of steps, and any prompts or cues that may be needed.

- Teaching the task: Each step of the task is taught to the student using direct instruction, modeling, or other teaching strategies. It is important to provide clear and concise instructions and to use a variety of teaching methods that are appropriate for the student’s learning style.

- Practice and feedback: The student is given opportunities to practice each step until they can perform it correctly and independently. Feedback and support are provided as needed, and the student is encouraged to ask questions and seek clarification if needed.

- Integrating steps: Once the student has mastered each step, they are gradually integrated into a complete task. The teacher or caregiver may provide additional support and guidance as needed, and the student is encouraged to practice the task until they are able to perform it independently.

Examples of task analysis in special education

Summarized below are some examples that will help gain a deeper understanding of the power of task analysis and how it can be applied in their own educational setting. So buckle up, and let’s dive into the exciting world of task analysis in education!

1. Writing

Task analysis can be a powerful tool for identifying the component skills involved in writing, and breaking them down into smaller, more manageable parts. These skills may include brainstorming , outlining, drafting, revising, and editing. By teaching each skill separately and explicitly, teachers can help students develop a more robust writing skill set.

For example, students can learn how to generate ideas and organize them into a logical structure using outlining techniques as well as graphic organizers which can help arrange the data for meaningful writing afterward. They can then focus on writing a coherent and well-structured draft, before revising it for clarity, coherence, and cohesion. Finally, they can edit their writing for grammar, punctuation, and spelling errors.

This approach can also help students identify their strengths and weaknesses in writing, and target areas for improvement. Students who struggle with generating ideas, for example, can receive targeted instruction on how to generate ideas and organize them effectively. Similarly, students who struggle with editing can receive targeted instruction on how to identify and correct common errors. By breaking down the writing process into discrete sub-tasks, and providing targeted instruction and feedback on each one, teachers can help students become more confident, competent writers.

2. Math problem-solving

Task analysis can be useful for deconstructing the complex process of solving math problems into a set of smaller, more manageable steps. These steps may include reading and understanding the problem statement, identifying relevant information, selecting an appropriate strategy, carrying out calculations accurately, and checking the solution for errors. By teaching each step separately, teachers can help students develop a more robust problem-solving skillset.

Students who struggle with selecting an appropriate strategy, for example, can receive targeted instruction on how to use problem-solving heuristics such as working backward or making a diagram. Similarly, students who struggle with carrying out calculations accurately can receive targeted instruction on how to use mathematical operations and formulas effectively. By breaking down the problem-solving process into discrete sub-tasks, and providing targeted instruction and feedback on each one, teachers can help students become more confident and competent math problem solvers.

3. Reading comprehension

Task analysis can be an effective way to help students develop their reading comprehension skills. Reading comprehension involves a complex set of cognitive processes, such as activating background knowledge, identifying the main idea, making inferences, predicting outcomes, and synthesizing information. By breaking down these skills into smaller, more manageable parts, teachers can help students become more proficient readers.

This method can assist children in becoming more engaged readers and developing critical thinking abilities. Teachers may help children become more confident and proficient readers by breaking down the reading comprehension process into discrete subtasks and offering targeted teaching and feedback on each one.

4. Laboratory experiments

Task analysis may be a useful method for teaching students how to plan and carry out scientific studies. Identifying the research topic, planning the study, choosing and measuring variables, controlling for confounding factors, and evaluating the results are all processes in a laboratory experiment. Teachers may assist children to build their scientific inquiry abilities by dividing these stages down into smaller, more manageable components.

For example, by examining scientific literature and discussing ideas, students might learn how to identify a research question. The research can then be designed by selecting relevant variables and controls. They can also learn how to effectively measure variables and account for confounding factors. Finally, kids can learn how to assess experiment data and form conclusions. This technique can help students become more involved and proficient scientists, as well as improve their critical thinking and problem-solving abilities.

5. Language learning

Task analysis can be a useful tool for language teachers to break down language learning into smaller, more manageable parts. Language learning involves a range of skills, including listening, speaking, reading, and writing, as well as grammatical and vocabulary knowledge. By breaking down these skills into discrete sub-tasks, teachers can provide targeted instruction and feedback to help students develop their language proficiency. For example, students can learn how to listen for specific information, understand the main points of a conversation or lecture, and respond appropriately.

They can also learn how to speak clearly, express their ideas, and ask questions in different situations. In addition, students can learn how to read and comprehend different types of texts, such as news articles, academic papers, and literary works. This can include skills such as understanding the structure of a text, identifying key information, and inferring meaning from context. Teachers can also introduce new vocabulary words and provide opportunities for students to use them in context, such as in a conversation or writing exercise.

What is the purpose of task analysis?

Task analysis is used in a variety of settings, but it is particularly important in special education. The goal of task analysis in special education is to support individuals with disabilities in acquiring new skills, improving existing ones, and becoming more independent.

Task analysis has several benefits. First, it allows educators to assess a student’s strengths and weaknesses, identify areas that need improvement, and develop a plan of action to support their growth and development. By breaking down tasks into smaller, more manageable steps, special education teachers can provide targeted instruction and support to help students acquire new skills, build confidence, and improve their overall functioning.

In addition, task analysis can help students understand and perform complex tasks more effectively. By breaking down tasks into smaller steps, students can see the connections between different parts of the task and understand how they fit together. This can lead to improved memory and problem-solving skills and greater overall independence.

Task analysis also provides a way to track progress over time. By regularly assessing and re-analyzing tasks, educators can see how students are developing and adjust their instruction and support accordingly. This can help ensure that students are making steady progress toward their goals.

What are the advantages of task analysis in special education?

Task analysis in special education offers several advantages that make it an important tool for supporting the development of individuals with disabilities. Some of the key advantages include:

1. Improved Learning Outcomes: By breaking down complex tasks into smaller, more manageable steps, task analysis can help individuals with disabilities acquire new skills and improve existing ones more effectively. This can lead to improved learning outcomes and greater overall independence. This can help teachers create an effective learning environment.

2. Targeted Instruction and Support: Task analysis allows educators to assess a student’s strengths and weaknesses and provide targeted instruction and support to help them overcome challenges and reach their full potential.

3. Increased Confidence: By breaking down tasks into smaller, more manageable parts, students can build confidence as they successfully complete each step. This can help build their self-esteem and increase their overall motivation to continue learning.

4. Better Understanding of Tasks: Task analysis helps students understand complex tasks more effectively by breaking them down into smaller, more manageable steps. This can improve their problem-solving skills and overall independence.

5. Improved Memory: Task analysis can improve memory by breaking down tasks into smaller steps that are easier to remember. This can lead to improved recall and performance over time.

6. Regular Progress Monitoring: Task analysis provides a way to track progress over time, which can help ensure that students are making steady progress toward their goals.

Task analysis in special education benefits not only students but also teachers and the special education community as a whole. This can result in a more positive and productive learning environment, with improved outcomes for all involved. Additionally, task analysis can also foster collaboration between special education teachers and other professionals, such as occupational and physical therapists. By working together to analyze tasks and determine the best ways to support students, these professionals can develop a more comprehensive and effective approach to meeting the needs of individuals with disabilities.

I am Shweta Sharma. I am a final year Masters student of Clinical Psychology and have been working closely in the field of psycho-education and child development. I have served in various organisations and NGOs with the purpose of helping children with disabilities learn and adapt better to both, academic and social challenges. I am keen on writing about learning difficulties, the science behind them and potential strategies to deal with them. My areas of expertise include putting forward the cognitive and behavioural aspects of disabilities for better awareness, as well as efficient intervention. Follow me on LinkedIn

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Information

- Author Services

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.

Editor’s Choice articles are based on recommendations by the scientific editors of MDPI journals from around the world. Editors select a small number of articles recently published in the journal that they believe will be particularly interesting to readers, or important in the respective research area. The aim is to provide a snapshot of some of the most exciting work published in the various research areas of the journal.

Original Submission Date Received: .

- Active Journals

- Find a Journal

- Proceedings Series

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

- For Societies

- For Conference Organizers

- Open Access Policy

- Institutional Open Access Program

- Special Issues Guidelines

- Editorial Process

- Research and Publication Ethics

- Article Processing Charges

- Testimonials

- Preprints.org

- SciProfiles

- Encyclopedia

Article Menu

- Subscribe SciFeed

- Recommended Articles

- Google Scholar

- on Google Scholar

- Table of Contents

Find support for a specific problem in the support section of our website.

Please let us know what you think of our products and services.

Visit our dedicated information section to learn more about MDPI.

JSmol Viewer

Research on outlier detection methods for dam monitoring data based on post-data classification, 1. introduction, 2. data set pre-classification, 3. outlier detection after pre-classification of data sets, 3.1. 3-sigma rule for outlier detection, 3.2. k-medoids machine learning algorithm for outlier detection.

| K-medoids Machine Learning Algorithm for Outlier Detection |

| Input: Data set D = {x1, x2, …, xn}, Number of clusters K, Maximum number of iterations M |

| Output: Clustering results clusters, Outliers outliers |

| 1: Select initial medoids as m ,m ;…,m |

| 2: Initialize total cost to infinity cost = ∞ |

| 3: iteration = 1 to M // |

| 4: For all x∈D and all m∈Medoids, calculate distance d(x,m)//Calculate the distance from each data point to each medoid |

| 5: For each x∈D, find min d(x,m) and assign x to the corresponding cluster//Assign each data point to the nearest medoid to form clusters |

| 6: For each cluster C, find the new center m′ = min ∑ d(x,x ) and calculate the cost cost // Recalculate the new center point (medoid) and cost for each cluster |

| 7: current cost <cost // Compare costs |

| 8: Update medoids |

| 9: Update total cost costtotal = ∑cost |

| 10: |

| 11: // Terminate if there is no cost improvement |

| 12: |

| 13: |

| 14: Set the threshold for determining outliers // Select based on the actual problem context |

| 15: Mark those points whose distance from the medoid exceeds the threshold as outliers // Mark outliers |

| 16: clusters and outliers // Return results |

3.3. Isolation Forest Machine Learning Algorithm for Outlier Detection

3.4. evaluation of outlier detection algorithm matching based on data set pre-classification, 4. conclusions, author contributions, data availability statement, acknowledgments, conflicts of interest.

- Jeon, J.; Lee, J.; Shin, D.; Park, H. Development of dam safety management system. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2009 , 40 , 554–563. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Abdelalim, A.M.; Said, S.O.; Alnaser, A.A.; Sharaf, A.; ElSamadony, A.; Kontoni, D.P.N.; Tantawy, M. Agent-Based Modeling for Construction Resource Positioning Using Digital Twin and BLE Technologies. Buildings 2024 , 14 , 1788. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Guo, M.; Qi, H.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, Y. Design and Management of a Spatial Database for Monitoring Building Comfort and Safety. Buildings 2023 , 13 , 2982. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Cai, S.; Li, L.; Li, S.; Sun, R.; Yuan, G. An efficient approach for outlier detection from uncertain data streams based on maximal frequent patterns. Expert Syst. Appl. 2020 , 160 , 113646. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Erkuş, E.C.; Purutçuoğlu, V. Outlier detection and quasi-periodicity optimization algorithm: Frequency domain based outlier detection (FOD). Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2021 , 291 , 560–574. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Zhou, Z.Y.; Pi, D.C. Data streams oriented outlier detection method: A fast minimal infrequent pattern mining. Int. Arab J. Inf. Technol. 2021 , 18 , 864–870. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Huang, Y.; Liu, W.; Li, S.; Guo, Y.; Chen, W. Interpretable Single-dimension Outlier Detection (ISOD): An Unsupervised Outlier Detection Method Based on Quantiles and Skewness Coefficients. Appl. Sci. 2023 , 14 , 136. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Cai, S.; Li, L.; Li, Q.; Li, S.; Hao, S.; Sun, R. UWFP-Outlier: An efficient frequent-pattern-based outlier detection method for uncertain weighted data streams. Appl. Intell. 2020 , 50 , 3452–3470. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Ding, Y.; Nie, M.; Xu, Y.; Miao, H. A Classification Method of Earthquake Ground Motion Records Based on the Results of K-Means Clustering Analysis. Buildings 2024 , 14 , 1831. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Weckenmann, A.; Jiang, X.; Sommer, K.D.; Neuschaefer-Rube, U.; Seewig, J.; Shaw, L.; Estler, T. Multisensor data fusion in dimensional metrology. CIRP Ann. 2009 , 58 , 701–721. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]