An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Indian J Crit Care Med

- v.23(Suppl 3); 2019 Sep

An Introduction to Statistics: Understanding Hypothesis Testing and Statistical Errors

Priya ranganathan.

1 Department of Anesthesiology, Critical Care and Pain, Tata Memorial Hospital, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

2 Department of Surgical Oncology, Tata Memorial Centre, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

The second article in this series on biostatistics covers the concepts of sample, population, research hypotheses and statistical errors.

How to cite this article

Ranganathan P, Pramesh CS. An Introduction to Statistics: Understanding Hypothesis Testing and Statistical Errors. Indian J Crit Care Med 2019;23(Suppl 3):S230–S231.

Two papers quoted in this issue of the Indian Journal of Critical Care Medicine report. The results of studies aim to prove that a new intervention is better than (superior to) an existing treatment. In the ABLE study, the investigators wanted to show that transfusion of fresh red blood cells would be superior to standard-issue red cells in reducing 90-day mortality in ICU patients. 1 The PROPPR study was designed to prove that transfusion of a lower ratio of plasma and platelets to red cells would be superior to a higher ratio in decreasing 24-hour and 30-day mortality in critically ill patients. 2 These studies are known as superiority studies (as opposed to noninferiority or equivalence studies which will be discussed in a subsequent article).

SAMPLE VERSUS POPULATION

A sample represents a group of participants selected from the entire population. Since studies cannot be carried out on entire populations, researchers choose samples, which are representative of the population. This is similar to walking into a grocery store and examining a few grains of rice or wheat before purchasing an entire bag; we assume that the few grains that we select (the sample) are representative of the entire sack of grains (the population).

The results of the study are then extrapolated to generate inferences about the population. We do this using a process known as hypothesis testing. This means that the results of the study may not always be identical to the results we would expect to find in the population; i.e., there is the possibility that the study results may be erroneous.

HYPOTHESIS TESTING

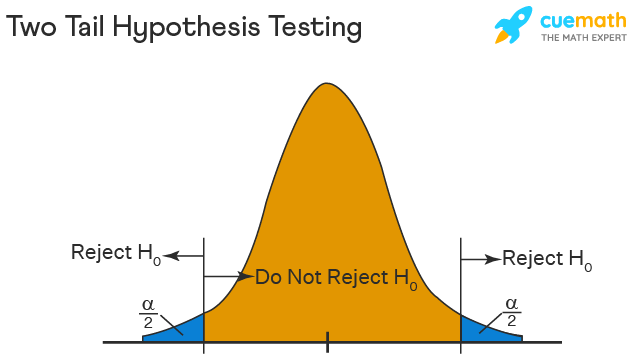

A clinical trial begins with an assumption or belief, and then proceeds to either prove or disprove this assumption. In statistical terms, this belief or assumption is known as a hypothesis. Counterintuitively, what the researcher believes in (or is trying to prove) is called the “alternate” hypothesis, and the opposite is called the “null” hypothesis; every study has a null hypothesis and an alternate hypothesis. For superiority studies, the alternate hypothesis states that one treatment (usually the new or experimental treatment) is superior to the other; the null hypothesis states that there is no difference between the treatments (the treatments are equal). For example, in the ABLE study, we start by stating the null hypothesis—there is no difference in mortality between groups receiving fresh RBCs and standard-issue RBCs. We then state the alternate hypothesis—There is a difference between groups receiving fresh RBCs and standard-issue RBCs. It is important to note that we have stated that the groups are different, without specifying which group will be better than the other. This is known as a two-tailed hypothesis and it allows us to test for superiority on either side (using a two-sided test). This is because, when we start a study, we are not 100% certain that the new treatment can only be better than the standard treatment—it could be worse, and if it is so, the study should pick it up as well. One tailed hypothesis and one-sided statistical testing is done for non-inferiority studies, which will be discussed in a subsequent paper in this series.

STATISTICAL ERRORS

There are two possibilities to consider when interpreting the results of a superiority study. The first possibility is that there is truly no difference between the treatments but the study finds that they are different. This is called a Type-1 error or false-positive error or alpha error. This means falsely rejecting the null hypothesis.

The second possibility is that there is a difference between the treatments and the study does not pick up this difference. This is called a Type 2 error or false-negative error or beta error. This means falsely accepting the null hypothesis.

The power of the study is the ability to detect a difference between groups and is the converse of the beta error; i.e., power = 1-beta error. Alpha and beta errors are finalized when the protocol is written and form the basis for sample size calculation for the study. In an ideal world, we would not like any error in the results of our study; however, we would need to do the study in the entire population (infinite sample size) to be able to get a 0% alpha and beta error. These two errors enable us to do studies with realistic sample sizes, with the compromise that there is a small possibility that the results may not always reflect the truth. The basis for this will be discussed in a subsequent paper in this series dealing with sample size calculation.

Conventionally, type 1 or alpha error is set at 5%. This means, that at the end of the study, if there is a difference between groups, we want to be 95% certain that this is a true difference and allow only a 5% probability that this difference has occurred by chance (false positive). Type 2 or beta error is usually set between 10% and 20%; therefore, the power of the study is 90% or 80%. This means that if there is a difference between groups, we want to be 80% (or 90%) certain that the study will detect that difference. For example, in the ABLE study, sample size was calculated with a type 1 error of 5% (two-sided) and power of 90% (type 2 error of 10%) (1).

Table 1 gives a summary of the two types of statistical errors with an example

Statistical errors

| (a) Types of statistical errors | |||

| : Null hypothesis is | |||

| True | False | ||

| Null hypothesis is actually | True | Correct results! | Falsely rejecting null hypothesis - Type I error |

| False | Falsely accepting null hypothesis - Type II error | Correct results! | |

| (b) Possible statistical errors in the ABLE trial | |||

| There is difference in mortality between groups receiving fresh RBCs and standard-issue RBCs | There difference in mortality between groups receiving fresh RBCs and standard-issue RBCs | ||

| Truth | There is difference in mortality between groups receiving fresh RBCs and standard-issue RBCs | Correct results! | Falsely rejecting null hypothesis - Type I error |

| There difference in mortality between groups receiving fresh RBCs and standard-issue RBCs | Falsely accepting null hypothesis - Type II error | Correct results! | |

In the next article in this series, we will look at the meaning and interpretation of ‘ p ’ value and confidence intervals for hypothesis testing.

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of interest: None

Introduction to Hypothesis Testing

A statistical hypothesis is an assumption about a population parameter .

For example, we may assume that the mean height of a male in the U.S. is 70 inches.

The assumption about the height is the statistical hypothesis and the true mean height of a male in the U.S. is the population parameter .

A hypothesis test is a formal statistical test we use to reject or fail to reject a statistical hypothesis.

The Two Types of Statistical Hypotheses

To test whether a statistical hypothesis about a population parameter is true, we obtain a random sample from the population and perform a hypothesis test on the sample data.

There are two types of statistical hypotheses:

The null hypothesis , denoted as H 0 , is the hypothesis that the sample data occurs purely from chance.

The alternative hypothesis , denoted as H 1 or H a , is the hypothesis that the sample data is influenced by some non-random cause.

Hypothesis Tests

A hypothesis test consists of five steps:

1. State the hypotheses.

State the null and alternative hypotheses. These two hypotheses need to be mutually exclusive, so if one is true then the other must be false.

2. Determine a significance level to use for the hypothesis.

Decide on a significance level. Common choices are .01, .05, and .1.

3. Find the test statistic.

Find the test statistic and the corresponding p-value. Often we are analyzing a population mean or proportion and the general formula to find the test statistic is: (sample statistic – population parameter) / (standard deviation of statistic)

4. Reject or fail to reject the null hypothesis.

Using the test statistic or the p-value, determine if you can reject or fail to reject the null hypothesis based on the significance level.

The p-value tells us the strength of evidence in support of a null hypothesis. If the p-value is less than the significance level, we reject the null hypothesis.

5. Interpret the results.

Interpret the results of the hypothesis test in the context of the question being asked.

The Two Types of Decision Errors

There are two types of decision errors that one can make when doing a hypothesis test:

Type I error: You reject the null hypothesis when it is actually true. The probability of committing a Type I error is equal to the significance level, often called alpha , and denoted as α.

Type II error: You fail to reject the null hypothesis when it is actually false. The probability of committing a Type II error is called the Power of the test or Beta , denoted as β.

One-Tailed and Two-Tailed Tests

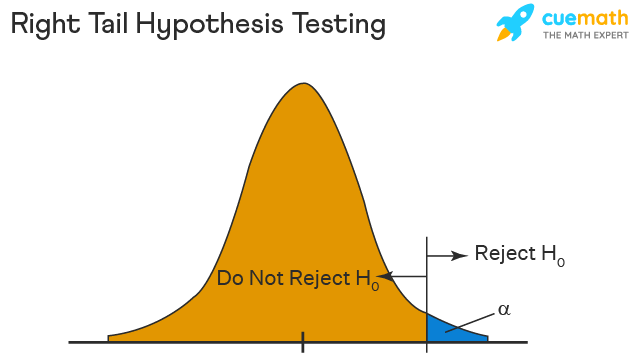

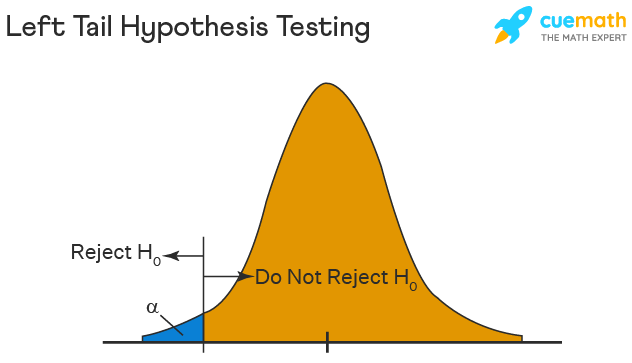

A statistical hypothesis can be one-tailed or two-tailed.

A one-tailed hypothesis involves making a “greater than” or “less than ” statement.

For example, suppose we assume the mean height of a male in the U.S. is greater than or equal to 70 inches. The null hypothesis would be H0: µ ≥ 70 inches and the alternative hypothesis would be Ha: µ < 70 inches.

A two-tailed hypothesis involves making an “equal to” or “not equal to” statement.

For example, suppose we assume the mean height of a male in the U.S. is equal to 70 inches. The null hypothesis would be H0: µ = 70 inches and the alternative hypothesis would be Ha: µ ≠ 70 inches.

Note: The “equal” sign is always included in the null hypothesis, whether it is =, ≥, or ≤.

Related: What is a Directional Hypothesis?

Types of Hypothesis Tests

There are many different types of hypothesis tests you can perform depending on the type of data you’re working with and the goal of your analysis.

The following tutorials provide an explanation of the most common types of hypothesis tests:

Introduction to the One Sample t-test Introduction to the Two Sample t-test Introduction to the Paired Samples t-test Introduction to the One Proportion Z-Test Introduction to the Two Proportion Z-Test

Featured Posts

Hey there. My name is Zach Bobbitt. I have a Masters of Science degree in Applied Statistics and I’ve worked on machine learning algorithms for professional businesses in both healthcare and retail. I’m passionate about statistics, machine learning, and data visualization and I created Statology to be a resource for both students and teachers alike. My goal with this site is to help you learn statistics through using simple terms, plenty of real-world examples, and helpful illustrations.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Join the Statology Community

Sign up to receive Statology's exclusive study resource: 100 practice problems with step-by-step solutions. Plus, get our latest insights, tutorials, and data analysis tips straight to your inbox!

By subscribing you accept Statology's Privacy Policy.

- Skip to secondary menu

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Statistics By Jim

Making statistics intuitive

Hypothesis Testing: Uses, Steps & Example

By Jim Frost 4 Comments

What is Hypothesis Testing?

Hypothesis testing in statistics uses sample data to infer the properties of a whole population . These tests determine whether a random sample provides sufficient evidence to conclude an effect or relationship exists in the population. Researchers use them to help separate genuine population-level effects from false effects that random chance can create in samples. These methods are also known as significance testing.

For example, researchers are testing a new medication to see if it lowers blood pressure. They compare a group taking the drug to a control group taking a placebo. If their hypothesis test results are statistically significant, the medication’s effect of lowering blood pressure likely exists in the broader population, not just the sample studied.

Using Hypothesis Tests

A hypothesis test evaluates two mutually exclusive statements about a population to determine which statement the sample data best supports. These two statements are called the null hypothesis and the alternative hypothesis . The following are typical examples:

- Null Hypothesis : The effect does not exist in the population.

- Alternative Hypothesis : The effect does exist in the population.

Hypothesis testing accounts for the inherent uncertainty of using a sample to draw conclusions about a population, which reduces the chances of false discoveries. These procedures determine whether the sample data are sufficiently inconsistent with the null hypothesis that you can reject it. If you can reject the null, your data favor the alternative statement that an effect exists in the population.

Statistical significance in hypothesis testing indicates that an effect you see in sample data also likely exists in the population after accounting for random sampling error , variability, and sample size. Your results are statistically significant when the p-value is less than your significance level or, equivalently, when your confidence interval excludes the null hypothesis value.

Conversely, non-significant results indicate that despite an apparent sample effect, you can’t be sure it exists in the population. It could be chance variation in the sample and not a genuine effect.

Learn more about Failing to Reject the Null .

5 Steps of Significance Testing

Hypothesis testing involves five key steps, each critical to validating a research hypothesis using statistical methods:

- Formulate the Hypotheses : Write your research hypotheses as a null hypothesis (H 0 ) and an alternative hypothesis (H A ).

- Data Collection : Gather data specifically aimed at testing the hypothesis.

- Conduct A Test : Use a suitable statistical test to analyze your data.

- Make a Decision : Based on the statistical test results, decide whether to reject the null hypothesis or fail to reject it.

- Report the Results : Summarize and present the outcomes in your report’s results and discussion sections.

While the specifics of these steps can vary depending on the research context and the data type, the fundamental process of hypothesis testing remains consistent across different studies.

Let’s work through these steps in an example!

Hypothesis Testing Example

Researchers want to determine if a new educational program improves student performance on standardized tests. They randomly assign 30 students to a control group , which follows the standard curriculum, and another 30 students to a treatment group, which participates in the new educational program. After a semester, they compare the test scores of both groups.

Download the CSV data file to perform the hypothesis testing yourself: Hypothesis_Testing .

The researchers write their hypotheses. These statements apply to the population, so they use the mu (μ) symbol for the population mean parameter .

- Null Hypothesis (H 0 ) : The population means of the test scores for the two groups are equal (μ 1 = μ 2 ).

- Alternative Hypothesis (H A ) : The population means of the test scores for the two groups are unequal (μ 1 ≠ μ 2 ).

Choosing the correct hypothesis test depends on attributes such as data type and number of groups. Because they’re using continuous data and comparing two means, the researchers use a 2-sample t-test .

Here are the results.

The treatment group’s mean is 58.70, compared to the control group’s mean of 48.12. The mean difference is 10.67 points. Use the test’s p-value and significance level to determine whether this difference is likely a product of random fluctuation in the sample or a genuine population effect.

Because the p-value (0.000) is less than the standard significance level of 0.05, the results are statistically significant, and we can reject the null hypothesis. The sample data provides sufficient evidence to conclude that the new program’s effect exists in the population.

Limitations

Hypothesis testing improves your effectiveness in making data-driven decisions. However, it is not 100% accurate because random samples occasionally produce fluky results. Hypothesis tests have two types of errors, both relating to drawing incorrect conclusions.

- Type I error: The test rejects a true null hypothesis—a false positive.

- Type II error: The test fails to reject a false null hypothesis—a false negative.

Learn more about Type I and Type II Errors .

Our exploration of hypothesis testing using a practical example of an educational program reveals its powerful ability to guide decisions based on statistical evidence. Whether you’re a student, researcher, or professional, understanding and applying these procedures can open new doors to discovering insights and making informed decisions. Let this tool empower your analytical endeavors as you navigate through the vast seas of data.

Learn more about the Hypothesis Tests for Various Data Types .

Share this:

Reader Interactions

June 10, 2024 at 10:51 am

Thank you, Jim, for another helpful article; timely too since I have started reading your new book on hypothesis testing and, now that we are at the end of the school year, my district is asking me to perform a number of evaluations on instructional programs. This is where my question/concern comes in. You mention that hypothesis testing is all about testing samples. However, I use all the students in my district when I make these comparisons. Since I am using the entire “population” in my evaluations (I don’t select a sample of third grade students, for example, but I use all 700 third graders), am I somehow misusing the tests? Or can I rest assured that my district’s student population is only a sample of the universal population of students?

June 10, 2024 at 1:50 pm

I hope you are finding the book helpful!

Yes, the purpose of hypothesis testing is to infer the properties of a population while accounting for random sampling error.

In your case, it comes down to how you want to use the results. Who do you want the results to apply to?

If you’re summarizing the sample, looking for trends and patterns, or evaluating those students and don’t plan to apply those results to other students, you don’t need hypothesis testing because there is no sampling error. They are the population and you can just use descriptive statistics. In this case, you’d only need to focus on the practical significance of the effect sizes.

On the other hand, if you want to apply the results from this group to other students, you’ll need hypothesis testing. However, there is the complicating issue of what population your sample of students represent. I’m sure your district has its own unique characteristics, demographics, etc. Your district’s students probably don’t adequately represent a universal population. At the very least, you’d need to recognize any special attributes of your district and how they could bias the results when trying to apply them outside the district. Or they might apply to similar districts in your region.

However, I’d imagine your 3rd graders probably adequately represent future classes of 3rd graders in your district. You need to be alert to changing demographics. At least in the short run I’d imagine they’d be representative of future classes.

Think about how these results will be used. Do they just apply to the students you measured? Then you don’t need hypothesis tests. However, if the results are being used to infer things about other students outside of the sample, you’ll need hypothesis testing along with considering how well your students represent the other students and how they differ.

I hope that helps!

June 10, 2024 at 3:21 pm

Thank you so much, Jim, for the suggestions in terms of what I need to think about and consider! You are always so clear in your explanations!!!!

June 10, 2024 at 3:22 pm

You’re very welcome! Best of luck with your evaluations!

Comments and Questions Cancel reply

User Preferences

Content preview.

Arcu felis bibendum ut tristique et egestas quis:

- Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris

- Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate

- Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident

Keyboard Shortcuts

S.3 hypothesis testing.

In reviewing hypothesis tests, we start first with the general idea. Then, we keep returning to the basic procedures of hypothesis testing, each time adding a little more detail.

The general idea of hypothesis testing involves:

- Making an initial assumption.

- Collecting evidence (data).

- Based on the available evidence (data), deciding whether to reject or not reject the initial assumption.

Every hypothesis test — regardless of the population parameter involved — requires the above three steps.

Example S.3.1

Is normal body temperature really 98.6 degrees f section .

Consider the population of many, many adults. A researcher hypothesized that the average adult body temperature is lower than the often-advertised 98.6 degrees F. That is, the researcher wants an answer to the question: "Is the average adult body temperature 98.6 degrees? Or is it lower?" To answer his research question, the researcher starts by assuming that the average adult body temperature was 98.6 degrees F.

Then, the researcher went out and tried to find evidence that refutes his initial assumption. In doing so, he selects a random sample of 130 adults. The average body temperature of the 130 sampled adults is 98.25 degrees.

Then, the researcher uses the data he collected to make a decision about his initial assumption. It is either likely or unlikely that the researcher would collect the evidence he did given his initial assumption that the average adult body temperature is 98.6 degrees:

- If it is likely , then the researcher does not reject his initial assumption that the average adult body temperature is 98.6 degrees. There is not enough evidence to do otherwise.

- either the researcher's initial assumption is correct and he experienced a very unusual event;

- or the researcher's initial assumption is incorrect.

In statistics, we generally don't make claims that require us to believe that a very unusual event happened. That is, in the practice of statistics, if the evidence (data) we collected is unlikely in light of the initial assumption, then we reject our initial assumption.

Example S.3.2

Criminal trial analogy section .

One place where you can consistently see the general idea of hypothesis testing in action is in criminal trials held in the United States. Our criminal justice system assumes "the defendant is innocent until proven guilty." That is, our initial assumption is that the defendant is innocent.

In the practice of statistics, we make our initial assumption when we state our two competing hypotheses -- the null hypothesis ( H 0 ) and the alternative hypothesis ( H A ). Here, our hypotheses are:

- H 0 : Defendant is not guilty (innocent)

- H A : Defendant is guilty

In statistics, we always assume the null hypothesis is true . That is, the null hypothesis is always our initial assumption.

The prosecution team then collects evidence — such as finger prints, blood spots, hair samples, carpet fibers, shoe prints, ransom notes, and handwriting samples — with the hopes of finding "sufficient evidence" to make the assumption of innocence refutable.

In statistics, the data are the evidence.

The jury then makes a decision based on the available evidence:

- If the jury finds sufficient evidence — beyond a reasonable doubt — to make the assumption of innocence refutable, the jury rejects the null hypothesis and deems the defendant guilty. We behave as if the defendant is guilty.

- If there is insufficient evidence, then the jury does not reject the null hypothesis . We behave as if the defendant is innocent.

In statistics, we always make one of two decisions. We either "reject the null hypothesis" or we "fail to reject the null hypothesis."

Errors in Hypothesis Testing Section

Did you notice the use of the phrase "behave as if" in the previous discussion? We "behave as if" the defendant is guilty; we do not "prove" that the defendant is guilty. And, we "behave as if" the defendant is innocent; we do not "prove" that the defendant is innocent.

This is a very important distinction! We make our decision based on evidence not on 100% guaranteed proof. Again:

- If we reject the null hypothesis, we do not prove that the alternative hypothesis is true.

- If we do not reject the null hypothesis, we do not prove that the null hypothesis is true.

We merely state that there is enough evidence to behave one way or the other. This is always true in statistics! Because of this, whatever the decision, there is always a chance that we made an error .

Let's review the two types of errors that can be made in criminal trials:

| Jury Decision | Truth | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Not Guilty | Guilty | ||

| Not Guilty | OK | ERROR | |

| Guilty | ERROR | OK | |

Table S.3.2 shows how this corresponds to the two types of errors in hypothesis testing.

| Decision | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Null Hypothesis | Alternative Hypothesis | ||

| Do not Reject Null | OK | Type II Error | |

| Reject Null | Type I Error | OK | |

Note that, in statistics, we call the two types of errors by two different names -- one is called a "Type I error," and the other is called a "Type II error." Here are the formal definitions of the two types of errors:

There is always a chance of making one of these errors. But, a good scientific study will minimize the chance of doing so!

Making the Decision Section

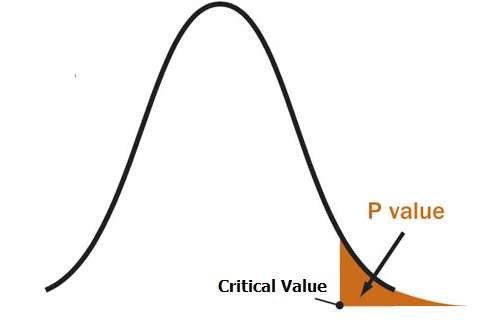

Recall that it is either likely or unlikely that we would observe the evidence we did given our initial assumption. If it is likely , we do not reject the null hypothesis. If it is unlikely , then we reject the null hypothesis in favor of the alternative hypothesis. Effectively, then, making the decision reduces to determining "likely" or "unlikely."

In statistics, there are two ways to determine whether the evidence is likely or unlikely given the initial assumption:

- We could take the " critical value approach " (favored in many of the older textbooks).

- Or, we could take the " P -value approach " (what is used most often in research, journal articles, and statistical software).

In the next two sections, we review the procedures behind each of these two approaches. To make our review concrete, let's imagine that μ is the average grade point average of all American students who major in mathematics. We first review the critical value approach for conducting each of the following three hypothesis tests about the population mean $\mu$:

| : = 3 | : > 3 | |

| : = 3 | : < 3 | |

| : = 3 | : ≠ 3 |

In Practice

- We would want to conduct the first hypothesis test if we were interested in concluding that the average grade point average of the group is more than 3.

- We would want to conduct the second hypothesis test if we were interested in concluding that the average grade point average of the group is less than 3.

- And, we would want to conduct the third hypothesis test if we were only interested in concluding that the average grade point average of the group differs from 3 (without caring whether it is more or less than 3).

Upon completing the review of the critical value approach, we review the P -value approach for conducting each of the above three hypothesis tests about the population mean \(\mu\). The procedures that we review here for both approaches easily extend to hypothesis tests about any other population parameter.

Reset password New user? Sign up

Existing user? Log in

Hypothesis Testing

Already have an account? Log in here.

A hypothesis test is a statistical inference method used to test the significance of a proposed (hypothesized) relation between population statistics (parameters) and their corresponding sample estimators . In other words, hypothesis tests are used to determine if there is enough evidence in a sample to prove a hypothesis true for the entire population.

The test considers two hypotheses: the null hypothesis , which is a statement meant to be tested, usually something like "there is no effect" with the intention of proving this false, and the alternate hypothesis , which is the statement meant to stand after the test is performed. The two hypotheses must be mutually exclusive ; moreover, in most applications, the two are complementary (one being the negation of the other). The test works by comparing the \(p\)-value to the level of significance (a chosen target). If the \(p\)-value is less than or equal to the level of significance, then the null hypothesis is rejected.

When analyzing data, only samples of a certain size might be manageable as efficient computations. In some situations the error terms follow a continuous or infinite distribution, hence the use of samples to suggest accuracy of the chosen test statistics. The method of hypothesis testing gives an advantage over guessing what distribution or which parameters the data follows.

Definitions and Methodology

Hypothesis test and confidence intervals.

In statistical inference, properties (parameters) of a population are analyzed by sampling data sets. Given assumptions on the distribution, i.e. a statistical model of the data, certain hypotheses can be deduced from the known behavior of the model. These hypotheses must be tested against sampled data from the population.

The null hypothesis \((\)denoted \(H_0)\) is a statement that is assumed to be true. If the null hypothesis is rejected, then there is enough evidence (statistical significance) to accept the alternate hypothesis \((\)denoted \(H_1).\) Before doing any test for significance, both hypotheses must be clearly stated and non-conflictive, i.e. mutually exclusive, statements. Rejecting the null hypothesis, given that it is true, is called a type I error and it is denoted \(\alpha\), which is also its probability of occurrence. Failing to reject the null hypothesis, given that it is false, is called a type II error and it is denoted \(\beta\), which is also its probability of occurrence. Also, \(\alpha\) is known as the significance level , and \(1-\beta\) is known as the power of the test. \(H_0\) \(\textbf{is true}\)\(\hspace{15mm}\) \(H_0\) \(\textbf{is false}\) \(\textbf{Reject}\) \(H_0\)\(\hspace{10mm}\) Type I error Correct Decision \(\textbf{Reject}\) \(H_1\) Correct Decision Type II error The test statistic is the standardized value following the sampled data under the assumption that the null hypothesis is true, and a chosen particular test. These tests depend on the statistic to be studied and the assumed distribution it follows, e.g. the population mean following a normal distribution. The \(p\)-value is the probability of observing an extreme test statistic in the direction of the alternate hypothesis, given that the null hypothesis is true. The critical value is the value of the assumed distribution of the test statistic such that the probability of making a type I error is small.

Methodologies: Given an estimator \(\hat \theta\) of a population statistic \(\theta\), following a probability distribution \(P(T)\), computed from a sample \(\mathcal{S},\) and given a significance level \(\alpha\) and test statistic \(t^*,\) define \(H_0\) and \(H_1;\) compute the test statistic \(t^*.\) \(p\)-value Approach (most prevalent): Find the \(p\)-value using \(t^*\) (right-tailed). If the \(p\)-value is at most \(\alpha,\) reject \(H_0\). Otherwise, reject \(H_1\). Critical Value Approach: Find the critical value solving the equation \(P(T\geq t_\alpha)=\alpha\) (right-tailed). If \(t^*>t_\alpha\), reject \(H_0\). Otherwise, reject \(H_1\). Note: Failing to reject \(H_0\) only means inability to accept \(H_1\), and it does not mean to accept \(H_0\).

Assume a normally distributed population has recorded cholesterol levels with various statistics computed. From a sample of 100 subjects in the population, the sample mean was 214.12 mg/dL (milligrams per deciliter), with a sample standard deviation of 45.71 mg/dL. Perform a hypothesis test, with significance level 0.05, to test if there is enough evidence to conclude that the population mean is larger than 200 mg/dL. Hypothesis Test We will perform a hypothesis test using the \(p\)-value approach with significance level \(\alpha=0.05:\) Define \(H_0\): \(\mu=200\). Define \(H_1\): \(\mu>200\). Since our values are normally distributed, the test statistic is \(z^*=\frac{\bar X - \mu_0}{\frac{s}{\sqrt{n}}}=\frac{214.12 - 200}{\frac{45.71}{\sqrt{100}}}\approx 3.09\). Using a standard normal distribution, we find that our \(p\)-value is approximately \(0.001\). Since the \(p\)-value is at most \(\alpha=0.05,\) we reject \(H_0\). Therefore, we can conclude that the test shows sufficient evidence to support the claim that \(\mu\) is larger than \(200\) mg/dL.

If the sample size was smaller, the normal and \(t\)-distributions behave differently. Also, the question itself must be managed by a double-tail test instead.

Assume a population's cholesterol levels are recorded and various statistics are computed. From a sample of 25 subjects, the sample mean was 214.12 mg/dL (milligrams per deciliter), with a sample standard deviation of 45.71 mg/dL. Perform a hypothesis test, with significance level 0.05, to test if there is enough evidence to conclude that the population mean is not equal to 200 mg/dL. Hypothesis Test We will perform a hypothesis test using the \(p\)-value approach with significance level \(\alpha=0.05\) and the \(t\)-distribution with 24 degrees of freedom: Define \(H_0\): \(\mu=200\). Define \(H_1\): \(\mu\neq 200\). Using the \(t\)-distribution, the test statistic is \(t^*=\frac{\bar X - \mu_0}{\frac{s}{\sqrt{n}}}=\frac{214.12 - 200}{\frac{45.71}{\sqrt{25}}}\approx 1.54\). Using a \(t\)-distribution with 24 degrees of freedom, we find that our \(p\)-value is approximately \(2(0.068)=0.136\). We have multiplied by two since this is a two-tailed argument, i.e. the mean can be smaller than or larger than. Since the \(p\)-value is larger than \(\alpha=0.05,\) we fail to reject \(H_0\). Therefore, the test does not show sufficient evidence to support the claim that \(\mu\) is not equal to \(200\) mg/dL.

The complement of the rejection on a two-tailed hypothesis test (with significance level \(\alpha\)) for a population parameter \(\theta\) is equivalent to finding a confidence interval \((\)with confidence level \(1-\alpha)\) for the population parameter \(\theta\). If the assumption on the parameter \(\theta\) falls inside the confidence interval, then the test has failed to reject the null hypothesis \((\)with \(p\)-value greater than \(\alpha).\) Otherwise, if \(\theta\) does not fall in the confidence interval, then the null hypothesis is rejected in favor of the alternate \((\)with \(p\)-value at most \(\alpha).\)

- Statistics (Estimation)

- Normal Distribution

- Correlation

- Confidence Intervals

Problem Loading...

Note Loading...

Set Loading...

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction

- Tabular methods

- Graphical methods

- Exploratory data analysis

- Events and their probabilities

- Random variables and probability distributions

- The binomial distribution

- The Poisson distribution

- The normal distribution

- Sampling and sampling distributions

- Estimation of a population mean

- Estimation of other parameters

- Estimation procedures for two populations

Hypothesis testing

Bayesian methods.

- Analysis of variance and significance testing

- Regression model

- Least squares method

- Analysis of variance and goodness of fit

- Significance testing

- Residual analysis

- Model building

- Correlation

- Time series and forecasting

- Nonparametric methods

- Acceptance sampling

- Statistical process control

- Sample survey methods

- Decision analysis

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Arizona State University - Educational Outreach and Student Services - Basic Statistics

- Princeton University - Probability and Statistics

- Statistics LibreTexts - Introduction to Statistics

- University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill - The Writing Center - Statistics

- Corporate Finance Institute - Statistics

- statistics - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- statistics - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

Hypothesis testing is a form of statistical inference that uses data from a sample to draw conclusions about a population parameter or a population probability distribution . First, a tentative assumption is made about the parameter or distribution. This assumption is called the null hypothesis and is denoted by H 0 . An alternative hypothesis (denoted H a ), which is the opposite of what is stated in the null hypothesis, is then defined. The hypothesis-testing procedure involves using sample data to determine whether or not H 0 can be rejected. If H 0 is rejected, the statistical conclusion is that the alternative hypothesis H a is true.

For example, assume that a radio station selects the music it plays based on the assumption that the average age of its listening audience is 30 years. To determine whether this assumption is valid, a hypothesis test could be conducted with the null hypothesis given as H 0 : μ = 30 and the alternative hypothesis given as H a : μ ≠ 30. Based on a sample of individuals from the listening audience, the sample mean age, x̄ , can be computed and used to determine whether there is sufficient statistical evidence to reject H 0 . Conceptually, a value of the sample mean that is “close” to 30 is consistent with the null hypothesis, while a value of the sample mean that is “not close” to 30 provides support for the alternative hypothesis. What is considered “close” and “not close” is determined by using the sampling distribution of x̄ .

Ideally, the hypothesis-testing procedure leads to the acceptance of H 0 when H 0 is true and the rejection of H 0 when H 0 is false. Unfortunately, since hypothesis tests are based on sample information, the possibility of errors must be considered. A type I error corresponds to rejecting H 0 when H 0 is actually true, and a type II error corresponds to accepting H 0 when H 0 is false. The probability of making a type I error is denoted by α, and the probability of making a type II error is denoted by β.

In using the hypothesis-testing procedure to determine if the null hypothesis should be rejected, the person conducting the hypothesis test specifies the maximum allowable probability of making a type I error, called the level of significance for the test. Common choices for the level of significance are α = 0.05 and α = 0.01. Although most applications of hypothesis testing control the probability of making a type I error, they do not always control the probability of making a type II error. A graph known as an operating-characteristic curve can be constructed to show how changes in the sample size affect the probability of making a type II error.

A concept known as the p -value provides a convenient basis for drawing conclusions in hypothesis-testing applications. The p -value is a measure of how likely the sample results are, assuming the null hypothesis is true; the smaller the p -value, the less likely the sample results. If the p -value is less than α, the null hypothesis can be rejected; otherwise, the null hypothesis cannot be rejected. The p -value is often called the observed level of significance for the test.

A hypothesis test can be performed on parameters of one or more populations as well as in a variety of other situations. In each instance, the process begins with the formulation of null and alternative hypotheses about the population. In addition to the population mean, hypothesis-testing procedures are available for population parameters such as proportions, variances , standard deviations , and medians .

Hypothesis tests are also conducted in regression and correlation analysis to determine if the regression relationship and the correlation coefficient are statistically significant (see below Regression and correlation analysis ). A goodness-of-fit test refers to a hypothesis test in which the null hypothesis is that the population has a specific probability distribution, such as a normal probability distribution. Nonparametric statistical methods also involve a variety of hypothesis-testing procedures.

The methods of statistical inference previously described are often referred to as classical methods. Bayesian methods (so called after the English mathematician Thomas Bayes ) provide alternatives that allow one to combine prior information about a population parameter with information contained in a sample to guide the statistical inference process. A prior probability distribution for a parameter of interest is specified first. Sample information is then obtained and combined through an application of Bayes’s theorem to provide a posterior probability distribution for the parameter. The posterior distribution provides the basis for statistical inferences concerning the parameter.

A key, and somewhat controversial, feature of Bayesian methods is the notion of a probability distribution for a population parameter. According to classical statistics, parameters are constants and cannot be represented as random variables. Bayesian proponents argue that, if a parameter value is unknown, then it makes sense to specify a probability distribution that describes the possible values for the parameter as well as their likelihood . The Bayesian approach permits the use of objective data or subjective opinion in specifying a prior distribution. With the Bayesian approach, different individuals might specify different prior distributions. Classical statisticians argue that for this reason Bayesian methods suffer from a lack of objectivity. Bayesian proponents argue that the classical methods of statistical inference have built-in subjectivity (through the choice of a sampling plan) and that the advantage of the Bayesian approach is that the subjectivity is made explicit.

Bayesian methods have been used extensively in statistical decision theory (see below Decision analysis ). In this context , Bayes’s theorem provides a mechanism for combining a prior probability distribution for the states of nature with sample information to provide a revised (posterior) probability distribution about the states of nature. These posterior probabilities are then used to make better decisions.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

8.1: The Elements of Hypothesis Testing

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 519

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Learning Objectives

- To understand the logical framework of tests of hypotheses.

- To learn basic terminology connected with hypothesis testing.

- To learn fundamental facts about hypothesis testing.

Types of Hypotheses

A hypothesis about the value of a population parameter is an assertion about its value. As in the introductory example we will be concerned with testing the truth of two competing hypotheses, only one of which can be true.

Definition: null hypothesis and alternative hypothesis

- The null hypothesis , denoted \(H_0\), is the statement about the population parameter that is assumed to be true unless there is convincing evidence to the contrary.

- The alternative hypothesis , denoted \(H_a\), is a statement about the population parameter that is contradictory to the null hypothesis, and is accepted as true only if there is convincing evidence in favor of it.

Definition: statistical procedure

Hypothesis testing is a statistical procedure in which a choice is made between a null hypothesis and an alternative hypothesis based on information in a sample.

The end result of a hypotheses testing procedure is a choice of one of the following two possible conclusions:

- Reject \(H_0\) (and therefore accept \(H_a\)), or

- Fail to reject \(H_0\) (and therefore fail to accept \(H_a\)).

The null hypothesis typically represents the status quo, or what has historically been true. In the example of the respirators, we would believe the claim of the manufacturer unless there is reason not to do so, so the null hypotheses is \(H_0:\mu =75\). The alternative hypothesis in the example is the contradictory statement \(H_a:\mu <75\). The null hypothesis will always be an assertion containing an equals sign, but depending on the situation the alternative hypothesis can have any one of three forms: with the symbol \(<\), as in the example just discussed, with the symbol \(>\), or with the symbol \(\neq\). The following two examples illustrate the latter two cases.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\)

A publisher of college textbooks claims that the average price of all hardbound college textbooks is \(\$127.50\). A student group believes that the actual mean is higher and wishes to test their belief. State the relevant null and alternative hypotheses.

The default option is to accept the publisher’s claim unless there is compelling evidence to the contrary. Thus the null hypothesis is \(H_0:\mu =127.50\). Since the student group thinks that the average textbook price is greater than the publisher’s figure, the alternative hypothesis in this situation is \(H_a:\mu >127.50\).

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\)

The recipe for a bakery item is designed to result in a product that contains \(8\) grams of fat per serving. The quality control department samples the product periodically to insure that the production process is working as designed. State the relevant null and alternative hypotheses.

The default option is to assume that the product contains the amount of fat it was formulated to contain unless there is compelling evidence to the contrary. Thus the null hypothesis is \(H_0:\mu =8.0\). Since to contain either more fat than desired or to contain less fat than desired are both an indication of a faulty production process, the alternative hypothesis in this situation is that the mean is different from \(8.0\), so \(H_a:\mu \neq 8.0\).

In Example \(\PageIndex{1}\), the textbook example, it might seem more natural that the publisher’s claim be that the average price is at most \(\$127.50\), not exactly \(\$127.50\). If the claim were made this way, then the null hypothesis would be \(H_0:\mu \leq 127.50\), and the value \(\$127.50\) given in the example would be the one that is least favorable to the publisher’s claim, the null hypothesis. It is always true that if the null hypothesis is retained for its least favorable value, then it is retained for every other value.

Thus in order to make the null and alternative hypotheses easy for the student to distinguish, in every example and problem in this text we will always present one of the two competing claims about the value of a parameter with an equality. The claim expressed with an equality is the null hypothesis. This is the same as always stating the null hypothesis in the least favorable light. So in the introductory example about the respirators, we stated the manufacturer’s claim as “the average is \(75\) minutes” instead of the perhaps more natural “the average is at least \(75\) minutes,” essentially reducing the presentation of the null hypothesis to its worst case.

The first step in hypothesis testing is to identify the null and alternative hypotheses.

The Logic of Hypothesis Testing

Although we will study hypothesis testing in situations other than for a single population mean (for example, for a population proportion instead of a mean or in comparing the means of two different populations), in this section the discussion will always be given in terms of a single population mean \(\mu\).

The null hypothesis always has the form \(H_0:\mu =\mu _0\) for a specific number \(\mu _0\) (in the respirator example \(\mu _0=75\), in the textbook example \(\mu _0=127.50\), and in the baked goods example \(\mu _0=8.0\)). Since the null hypothesis is accepted unless there is strong evidence to the contrary, the test procedure is based on the initial assumption that \(H_0\) is true. This point is so important that we will repeat it in a display:

The test procedure is based on the initial assumption that \(H_0\) is true.

The criterion for judging between \(H_0\) and \(H_a\) based on the sample data is: if the value of \(\overline{X}\) would be highly unlikely to occur if \(H_0\) were true, but favors the truth of \(H_a\), then we reject \(H_0\) in favor of \(H_a\). Otherwise we do not reject \(H_0\).

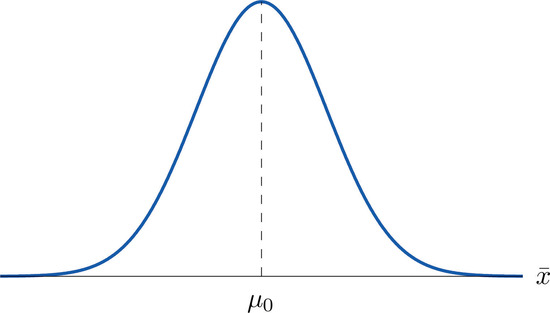

Supposing for now that \(\overline{X}\) follows a normal distribution, when the null hypothesis is true the density function for the sample mean \(\overline{X}\) must be as in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): a bell curve centered at \(\mu _0\). Thus if \(H_0\) is true then \(\overline{X}\) is likely to take a value near \(\mu _0\) and is unlikely to take values far away. Our decision procedure therefore reduces simply to:

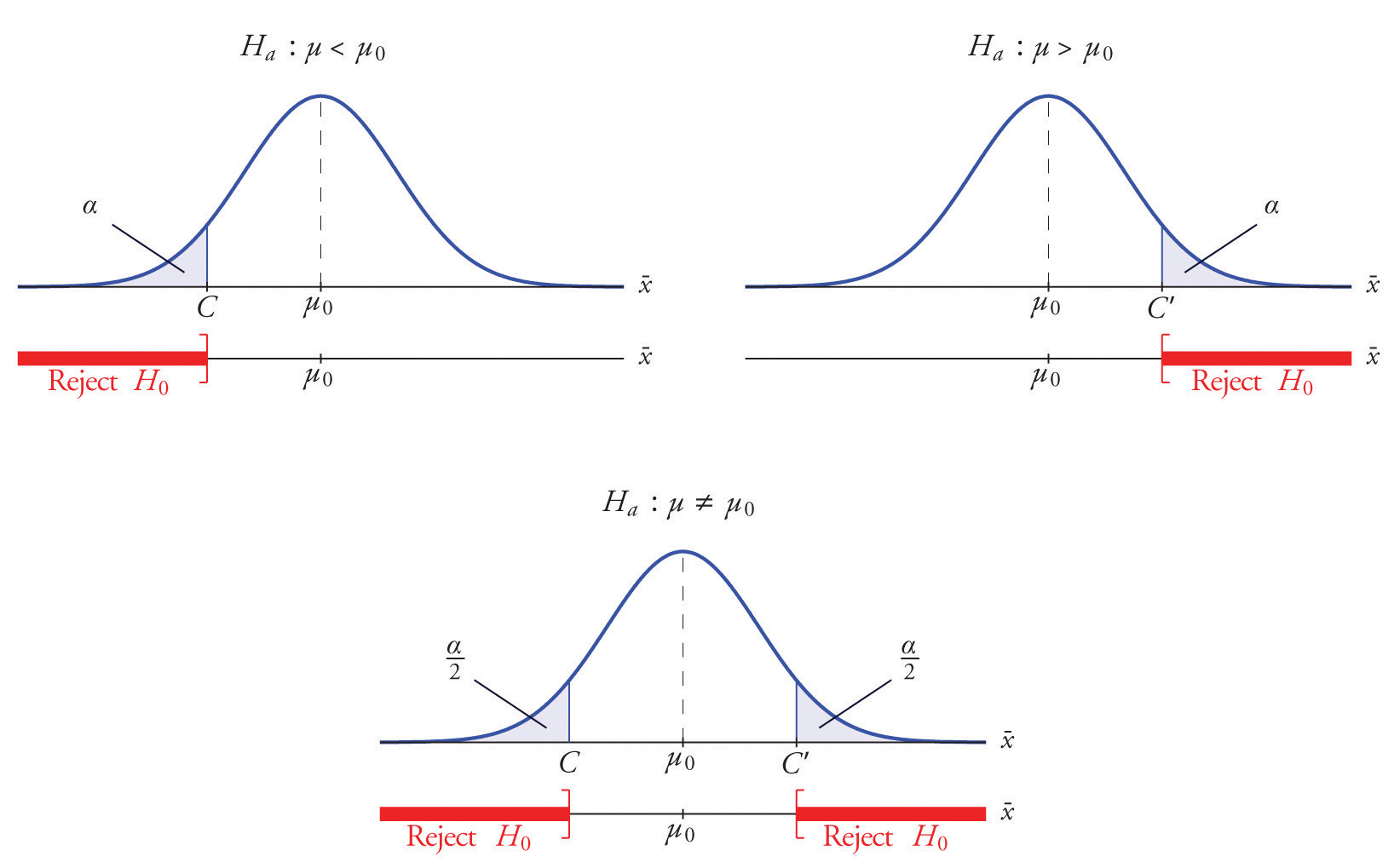

- if \(H_a\) has the form \(H_a:\mu <\mu _0\) then reject \(H_0\) if \(\bar{x}\) is far to the left of \(\mu _0\);

- if \(H_a\) has the form \(H_a:\mu >\mu _0\) then reject \(H_0\) if \(\bar{x}\) is far to the right of \(\mu _0\);

- if \(H_a\) has the form \(H_a:\mu \neq \mu _0\) then reject \(H_0\) if \(\bar{x}\) is far away from \(\mu _0\) in either direction.

Think of the respirator example, for which the null hypothesis is \(H_0:\mu =75\), the claim that the average time air is delivered for all respirators is \(75\) minutes. If the sample mean is \(75\) or greater then we certainly would not reject \(H_0\) (since there is no issue with an emergency respirator delivering air even longer than claimed).

If the sample mean is slightly less than \(75\) then we would logically attribute the difference to sampling error and also not reject \(H_0\) either.

Values of the sample mean that are smaller and smaller are less and less likely to come from a population for which the population mean is \(75\). Thus if the sample mean is far less than \(75\), say around \(60\) minutes or less, then we would certainly reject \(H_0\), because we know that it is highly unlikely that the average of a sample would be so low if the population mean were \(75\). This is the rare event criterion for rejection: what we actually observed \((\overline{X}<60)\) would be so rare an event if \(\mu =75\) were true that we regard it as much more likely that the alternative hypothesis \(\mu <75\) holds.

In summary, to decide between \(H_0\) and \(H_a\) in this example we would select a “rejection region” of values sufficiently far to the left of \(75\), based on the rare event criterion, and reject \(H_0\) if the sample mean \(\overline{X}\) lies in the rejection region, but not reject \(H_0\) if it does not.

The Rejection Region

Each different form of the alternative hypothesis Ha has its own kind of rejection region:

- if (as in the respirator example) \(H_a\) has the form \(H_a:\mu <\mu _0\), we reject \(H_0\) if \(\bar{x}\) is far to the left of \(\mu _0\), that is, to the left of some number \(C\), so the rejection region has the form of an interval \((-\infty ,C]\);

- if (as in the textbook example) \(H_a\) has the form \(H_a:\mu >\mu _0\), we reject \(H_0\) if \(\bar{x}\) is far to the right of \(\mu _0\), that is, to the right of some number \(C\), so the rejection region has the form of an interval \([C,\infty )\);

- if (as in the baked good example) \(H_a\) has the form \(H_a:\mu \neq \mu _0\), we reject \(H_0\) if \(\bar{x}\) is far away from \(\mu _0\) in either direction, that is, either to the left of some number \(C\) or to the right of some other number \(C′\), so the rejection region has the form of the union of two intervals \((-\infty ,C]\cup [C',\infty )\).

The key issue in our line of reasoning is the question of how to determine the number \(C\) or numbers \(C\) and \(C′\), called the critical value or critical values of the statistic, that determine the rejection region.

Definition: critical values

The critical value or critical values of a test of hypotheses are the number or numbers that determine the rejection region.

Suppose the rejection region is a single interval, so we need to select a single number \(C\). Here is the procedure for doing so. We select a small probability, denoted \(\alpha\), say \(1\%\), which we take as our definition of “rare event:” an event is “rare” if its probability of occurrence is less than \(\alpha\). (In all the examples and problems in this text the value of \(\alpha\) will be given already.) The probability that \(\overline{X}\) takes a value in an interval is the area under its density curve and above that interval, so as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\) (drawn under the assumption that \(H_0\) is true, so that the curve centers at \(\mu _0\)) the critical value \(C\) is the value of \(\overline{X}\) that cuts off a tail area \(\alpha\) in the probability density curve of \(\overline{X}\). When the rejection region is in two pieces, that is, composed of two intervals, the total area above both of them must be \(\alpha\), so the area above each one is \(\alpha /2\), as also shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\).

The number \(\alpha\) is the total area of a tail or a pair of tails.

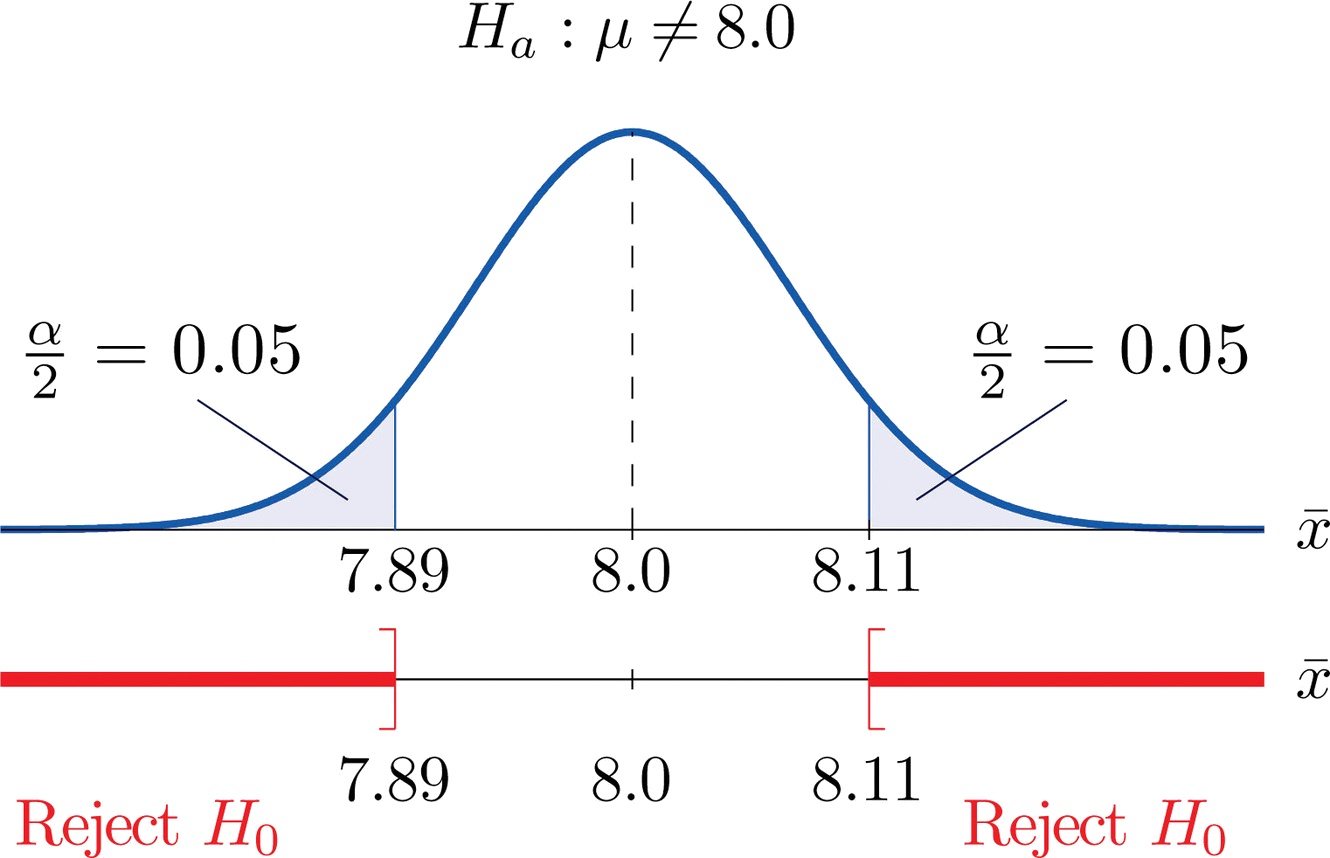

Example \(\PageIndex{3}\)

In the context of Example \(\PageIndex{2}\), suppose that it is known that the population is normally distributed with standard deviation \(\alpha =0.15\) gram, and suppose that the test of hypotheses \(H_0:\mu =8.0\) versus \(H_a:\mu \neq 8.0\) will be performed with a sample of size \(5\). Construct the rejection region for the test for the choice \(\alpha =0.10\). Explain the decision procedure and interpret it.

If \(H_0\) is true then the sample mean \(\overline{X}\) is normally distributed with mean and standard deviation

\[\begin{align} \mu _{\overline{X}} &=\mu \nonumber \\[5pt] &=8.0 \nonumber \end{align} \nonumber \]

\[\begin{align} \sigma _{\overline{X}}&=\dfrac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}} \nonumber \\[5pt] &= \dfrac{0.15}{\sqrt{5}} \nonumber\\[5pt] &=0.067 \nonumber \end{align} \nonumber \]

Since \(H_a\) contains the \(\neq\) symbol the rejection region will be in two pieces, each one corresponding to a tail of area \(\alpha /2=0.10/2=0.05\). From Figure 7.1.6, \(z_{0.05}=1.645\), so \(C\) and \(C′\) are \(1.645\) standard deviations of \(\overline{X}\) to the right and left of its mean \(8.0\):

\[C=8.0-(1.645)(0.067) = 7.89 \; \; \text{and}\; \; C'=8.0 + (1.645)(0.067) = 8.11 \nonumber \]

The result is shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\). α = 0.1

The decision procedure is: take a sample of size \(5\) and compute the sample mean \(\bar{x}\). If \(\bar{x}\) is either \(7.89\) grams or less or \(8.11\) grams or more then reject the hypothesis that the average amount of fat in all servings of the product is \(8.0\) grams in favor of the alternative that it is different from \(8.0\) grams. Otherwise do not reject the hypothesis that the average amount is \(8.0\) grams.

The reasoning is that if the true average amount of fat per serving were \(8.0\) grams then there would be less than a \(10\%\) chance that a sample of size \(5\) would produce a mean of either \(7.89\) grams or less or \(8.11\) grams or more. Hence if that happened it would be more likely that the value \(8.0\) is incorrect (always assuming that the population standard deviation is \(0.15\) gram).

Because the rejection regions are computed based on areas in tails of distributions, as shown in Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\), hypothesis tests are classified according to the form of the alternative hypothesis in the following way.

Definitions: Test classifications

- If \(H_a\) has the form \(\mu \neq \mu _0\) the test is called a two-tailed test .

- If \(H_a\) has the form \(\mu < \mu _0\) the test is called a left-tailed test .

- If \(H_a\) has the form \(\mu > \mu _0\)the test is called a right-tailed test .

Each of the last two forms is also called a one-tailed test .

Two Types of Errors

The format of the testing procedure in general terms is to take a sample and use the information it contains to come to a decision about the two hypotheses. As stated before our decision will always be either

- reject the null hypothesis \(H_0\) in favor of the alternative \(H_a\) presented, or

- do not reject the null hypothesis \(H_0\) in favor of the alternative \(H_0\) presented.

There are four possible outcomes of hypothesis testing procedure, as shown in the following table:

| True State of Nature | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| \(H_0\) is true | \(H_0\) is false | ||

| Our Decision | Do not reject \(H_0\) | Correct decision | Type II error |

| Reject \(H_0\) | Type I error | Correct decision | |

As the table shows, there are two ways to be right and two ways to be wrong. Typically to reject \(H_0\) when it is actually true is a more serious error than to fail to reject it when it is false, so the former error is labeled “ Type I ” and the latter error “ Type II ”.

Definition: Type I and Type II errors

In a test of hypotheses:

- A Type I error is the decision to reject \(H_0\) when it is in fact true.

- A Type II error is the decision not to reject \(H_0\) when it is in fact not true.

Unless we perform a census we do not have certain knowledge, so we do not know whether our decision matches the true state of nature or if we have made an error. We reject \(H_0\) if what we observe would be a “rare” event if \(H_0\) were true. But rare events are not impossible: they occur with probability \(\alpha\). Thus when \(H_0\) is true, a rare event will be observed in the proportion \(\alpha\) of repeated similar tests, and \(H_0\) will be erroneously rejected in those tests. Thus \(\alpha\) is the probability that in following the testing procedure to decide between \(H_0\) and \(H_a\) we will make a Type I error.

Definition: level of significance

The number \(\alpha\) that is used to determine the rejection region is called the level of significance of the test. It is the probability that the test procedure will result in a Type I error .

The probability of making a Type II error is too complicated to discuss in a beginning text, so we will say no more about it than this: for a fixed sample size, choosing \(alpha\) smaller in order to reduce the chance of making a Type I error has the effect of increasing the chance of making a Type II error . The only way to simultaneously reduce the chances of making either kind of error is to increase the sample size.

Standardizing the Test Statistic

Hypotheses testing will be considered in a number of contexts, and great unification as well as simplification results when the relevant sample statistic is standardized by subtracting its mean from it and then dividing by its standard deviation. The resulting statistic is called a standardized test statistic . In every situation treated in this and the following two chapters the standardized test statistic will have either the standard normal distribution or Student’s \(t\)-distribution.

Definition: hypothesis test

A standardized test statistic for a hypothesis test is the statistic that is formed by subtracting from the statistic of interest its mean and dividing by its standard deviation.

For example, reviewing Example \(\PageIndex{3}\), if instead of working with the sample mean \(\overline{X}\) we instead work with the test statistic

\[\frac{\overline{X}-8.0}{0.067} \nonumber \]

then the distribution involved is standard normal and the critical values are just \(\pm z_{0.05}\). The extra work that was done to find that \(C=7.89\) and \(C′=8.11\) is eliminated. In every hypothesis test in this book the standardized test statistic will be governed by either the standard normal distribution or Student’s \(t\)-distribution. Information about rejection regions is summarized in the following tables:

| Symbol in \(H_a\) | Terminology | Rejection Region |

|---|---|---|

| < | Left-tailed test | \((-\infty ,-z_\alpha ]\) |

| > | Right-tailed test | \([z_\alpha ,\infty )\) |

| ≠ | Two-tailed test | \((-\infty ,-z_{\alpha/2} ]\cup [z_{\alpha /2},\infty )\) |

| Symbol in \(H_a\) | Terminology | Rejection Region |

|---|---|---|

| < | Left-tailed test | \((-\infty ,-t_\alpha ]\) |

| > | Right-tailed test | \([t_\alpha ,\infty )\) |

| ≠ | Two-tailed test | \((-\infty ,-t_{\alpha/2} ]\cup [t_{\alpha /2},\infty )\) |

Every instance of hypothesis testing discussed in this and the following two chapters will have a rejection region like one of the six forms tabulated in the tables above.

No matter what the context a test of hypotheses can always be performed by applying the following systematic procedure, which will be illustrated in the examples in the succeeding sections.

Systematic Hypothesis Testing Procedure: Critical Value Approach

- Identify the null and alternative hypotheses.

- Identify the relevant test statistic and its distribution.

- Compute from the data the value of the test statistic.

- Construct the rejection region.

- Compare the value computed in Step 3 to the rejection region constructed in Step 4 and make a decision. Formulate the decision in the context of the problem, if applicable.

The procedure that we have outlined in this section is called the “Critical Value Approach” to hypothesis testing to distinguish it from an alternative but equivalent approach that will be introduced at the end of Section 8.3.

Key Takeaway

- A test of hypotheses is a statistical process for deciding between two competing assertions about a population parameter.

- The testing procedure is formalized in a five-step procedure.

Tutorial Playlist

Statistics tutorial, everything you need to know about the probability density function in statistics, the best guide to understand central limit theorem, an in-depth guide to measures of central tendency : mean, median and mode, the ultimate guide to understand conditional probability.

A Comprehensive Look at Percentile in Statistics

The Best Guide to Understand Bayes Theorem

Everything you need to know about the normal distribution, an in-depth explanation of cumulative distribution function, a complete guide to chi-square test, what is hypothesis testing in statistics types and examples, understanding the fundamentals of arithmetic and geometric progression, the definitive guide to understand spearman’s rank correlation, mean squared error: overview, examples, concepts and more, all you need to know about the empirical rule in statistics, the complete guide to skewness and kurtosis, a holistic look at bernoulli distribution.

All You Need to Know About Bias in Statistics

A Complete Guide to Get a Grasp of Time Series Analysis

The Key Differences Between Z-Test Vs. T-Test

The Complete Guide to Understand Pearson's Correlation

A complete guide on the types of statistical studies, everything you need to know about poisson distribution, your best guide to understand correlation vs. regression, the most comprehensive guide for beginners on what is correlation, hypothesis testing in statistics - types | examples.

Lesson 10 of 24 By Avijeet Biswal

Table of Contents

In today’s data-driven world, decisions are based on data all the time. Hypothesis plays a crucial role in that process, whether it may be making business decisions, in the health sector, academia, or in quality improvement. Without hypothesis & hypothesis tests, you risk drawing the wrong conclusions and making bad decisions. In this tutorial, you will look at Hypothesis Testing in Statistics.

The Ultimate Ticket to Top Data Science Job Roles

What Is Hypothesis Testing in Statistics?

Hypothesis Testing is a type of statistical analysis in which you put your assumptions about a population parameter to the test. It is used to estimate the relationship between 2 statistical variables.

Let's discuss few examples of statistical hypothesis from real-life -

- A teacher assumes that 60% of his college's students come from lower-middle-class families.

- A doctor believes that 3D (Diet, Dose, and Discipline) is 90% effective for diabetic patients.

Now that you know about hypothesis testing, look at the two types of hypothesis testing in statistics.

Hypothesis Testing Formula

Z = ( x̅ – μ0 ) / (σ /√n)

- Here, x̅ is the sample mean,

- μ0 is the population mean,

- σ is the standard deviation,

- n is the sample size.

How Hypothesis Testing Works?

An analyst performs hypothesis testing on a statistical sample to present evidence of the plausibility of the null hypothesis. Measurements and analyses are conducted on a random sample of the population to test a theory. Analysts use a random population sample to test two hypotheses: the null and alternative hypotheses.

The null hypothesis is typically an equality hypothesis between population parameters; for example, a null hypothesis may claim that the population means return equals zero. The alternate hypothesis is essentially the inverse of the null hypothesis (e.g., the population means the return is not equal to zero). As a result, they are mutually exclusive, and only one can be correct. One of the two possibilities, however, will always be correct.

Your Dream Career is Just Around The Corner!

Null Hypothesis and Alternative Hypothesis

The Null Hypothesis is the assumption that the event will not occur. A null hypothesis has no bearing on the study's outcome unless it is rejected.

H0 is the symbol for it, and it is pronounced H-naught.

The Alternate Hypothesis is the logical opposite of the null hypothesis. The acceptance of the alternative hypothesis follows the rejection of the null hypothesis. H1 is the symbol for it.

Let's understand this with an example.

A sanitizer manufacturer claims that its product kills 95 percent of germs on average.

To put this company's claim to the test, create a null and alternate hypothesis.

H0 (Null Hypothesis): Average = 95%.

Alternative Hypothesis (H1): The average is less than 95%.

Another straightforward example to understand this concept is determining whether or not a coin is fair and balanced. The null hypothesis states that the probability of a show of heads is equal to the likelihood of a show of tails. In contrast, the alternate theory states that the probability of a show of heads and tails would be very different.

Become a Data Scientist with Hands-on Training!

Hypothesis Testing Calculation With Examples

Let's consider a hypothesis test for the average height of women in the United States. Suppose our null hypothesis is that the average height is 5'4". We gather a sample of 100 women and determine that their average height is 5'5". The standard deviation of population is 2.

To calculate the z-score, we would use the following formula:

z = ( x̅ – μ0 ) / (σ /√n)

z = (5'5" - 5'4") / (2" / √100)

z = 0.5 / (0.045)

We will reject the null hypothesis as the z-score of 11.11 is very large and conclude that there is evidence to suggest that the average height of women in the US is greater than 5'4".

Steps in Hypothesis Testing

Hypothesis testing is a statistical method to determine if there is enough evidence in a sample of data to infer that a certain condition is true for the entire population. Here’s a breakdown of the typical steps involved in hypothesis testing:

Formulate Hypotheses

- Null Hypothesis (H0): This hypothesis states that there is no effect or difference, and it is the hypothesis you attempt to reject with your test.

- Alternative Hypothesis (H1 or Ha): This hypothesis is what you might believe to be true or hope to prove true. It is usually considered the opposite of the null hypothesis.

Choose the Significance Level (α)

The significance level, often denoted by alpha (α), is the probability of rejecting the null hypothesis when it is true. Common choices for α are 0.05 (5%), 0.01 (1%), and 0.10 (10%).

Select the Appropriate Test

Choose a statistical test based on the type of data and the hypothesis. Common tests include t-tests, chi-square tests, ANOVA, and regression analysis. The selection depends on data type, distribution, sample size, and whether the hypothesis is one-tailed or two-tailed.

Collect Data

Gather the data that will be analyzed in the test. This data should be representative of the population to infer conclusions accurately.

Calculate the Test Statistic

Based on the collected data and the chosen test, calculate a test statistic that reflects how much the observed data deviates from the null hypothesis.

Determine the p-value

The p-value is the probability of observing test results at least as extreme as the results observed, assuming the null hypothesis is correct. It helps determine the strength of the evidence against the null hypothesis.

Make a Decision

Compare the p-value to the chosen significance level:

- If the p-value ≤ α: Reject the null hypothesis, suggesting sufficient evidence in the data supports the alternative hypothesis.

- If the p-value > α: Do not reject the null hypothesis, suggesting insufficient evidence to support the alternative hypothesis.

Report the Results

Present the findings from the hypothesis test, including the test statistic, p-value, and the conclusion about the hypotheses.

Perform Post-hoc Analysis (if necessary)

Depending on the results and the study design, further analysis may be needed to explore the data more deeply or to address multiple comparisons if several hypotheses were tested simultaneously.

Types of Hypothesis Testing

To determine whether a discovery or relationship is statistically significant, hypothesis testing uses a z-test. It usually checks to see if two means are the same (the null hypothesis). Only when the population standard deviation is known and the sample size is 30 data points or more, can a z-test be applied.

A statistical test called a t-test is employed to compare the means of two groups. To determine whether two groups differ or if a procedure or treatment affects the population of interest, it is frequently used in hypothesis testing.

Chi-Square

You utilize a Chi-square test for hypothesis testing concerning whether your data is as predicted. To determine if the expected and observed results are well-fitted, the Chi-square test analyzes the differences between categorical variables from a random sample. The test's fundamental premise is that the observed values in your data should be compared to the predicted values that would be present if the null hypothesis were true.

Hypothesis Testing and Confidence Intervals

Both confidence intervals and hypothesis tests are inferential techniques that depend on approximating the sample distribution. Data from a sample is used to estimate a population parameter using confidence intervals. Data from a sample is used in hypothesis testing to examine a given hypothesis. We must have a postulated parameter to conduct hypothesis testing.

Bootstrap distributions and randomization distributions are created using comparable simulation techniques. The observed sample statistic is the focal point of a bootstrap distribution, whereas the null hypothesis value is the focal point of a randomization distribution.

A variety of feasible population parameter estimates are included in confidence ranges. In this lesson, we created just two-tailed confidence intervals. There is a direct connection between these two-tail confidence intervals and these two-tail hypothesis tests. The results of a two-tailed hypothesis test and two-tailed confidence intervals typically provide the same results. In other words, a hypothesis test at the 0.05 level will virtually always fail to reject the null hypothesis if the 95% confidence interval contains the predicted value. A hypothesis test at the 0.05 level will nearly certainly reject the null hypothesis if the 95% confidence interval does not include the hypothesized parameter.

Become a Data Scientist through hands-on learning with hackathons, masterclasses, webinars, and Ask-Me-Anything! Start learning now!

Simple and Composite Hypothesis Testing

Depending on the population distribution, you can classify the statistical hypothesis into two types.

Simple Hypothesis: A simple hypothesis specifies an exact value for the parameter.

Composite Hypothesis: A composite hypothesis specifies a range of values.

A company is claiming that their average sales for this quarter are 1000 units. This is an example of a simple hypothesis.

Suppose the company claims that the sales are in the range of 900 to 1000 units. Then this is a case of a composite hypothesis.

One-Tailed and Two-Tailed Hypothesis Testing

The One-Tailed test, also called a directional test, considers a critical region of data that would result in the null hypothesis being rejected if the test sample falls into it, inevitably meaning the acceptance of the alternate hypothesis.

In a one-tailed test, the critical distribution area is one-sided, meaning the test sample is either greater or lesser than a specific value.

In two tails, the test sample is checked to be greater or less than a range of values in a Two-Tailed test, implying that the critical distribution area is two-sided.