Case Studies

This page provides an overview of the various case studies available from Scrum.org. These case studies demonstrate successful transforming organizations, uses of Scrum, Nexus, Evidence-Based Management and more. Read them to understand where people and teams have struggled and how they have overcome their struggles.

Organizational and Cultural Transformation

Scaling scrum, successfully implementing scrum, scrum outside of software.

Search All Case Studies

What did you think about this content?

For enquiries call:

+1-469-442-0620

Agile Case Studies: Examples Across Various Industires

Home Blog Agile Agile Case Studies: Examples Across Various Industires

Agile methodologies have gained significant popularity in project management and product development. Various industries have successfully applied Agile principles, showcasing experiences, challenges, and benefits. Case studies demonstrate Agile's versatility in software development, manufacturing, and service sectors. These real-world examples offer practical insights into Agile implementation, challenges faced, and strategies to overcome them. Agile case studies provide valuable inspiration for implementing these methodologies in any project, regardless of the organization's size or industry.

Who Uses Agile Methodology?

Agile methodology is used by a wide variety of organizations, including:

- Software development companies use Agile to improve collaboration, increase flexibility, and deliver high-quality software incrementally.

- IT departments use agile to manage and execute projects efficiently, respond to changing requirements, and deliver value to stakeholders in a timely manner.

- Startups use agile to quickly adapt to market changes and iterate on product development based on customer feedback.

- Marketing and advertising agencies use agile to enhance campaign management, creative development, and customer engagement strategies.

- Product development teams use agile to iterate, test, and refine their designs and manufacturing processes.

- Project management teams use agile to enhance project execution, facilitate collaboration, and manage complex projects with changing requirements.

- Retail companies use agile to develop new marketing campaigns and improve their website and e-commerce platform.

Agile Case Study Examples

1. moving towards agile: managing loxon solutions.

Following is an Agile case study in banking:

Loxon Solutions, a Hungarian technology startup in the banking software industry, faced several challenges in its journey towards becoming an agile organization. As the company experienced rapid growth, it struggled with its hiring strategy, organizational development, and successful implementation of agile practices.

How was it solved:

Loxon Solutions implemented a structured recruitment process with targeted job postings and rigorous interviews to attract skilled candidates. They restructured the company into cross-functional teams, promoting better collaboration. Agile management training and coaching were provided to all employees, with online courses playing a crucial role. Agile teams with trained Scrum Masters and Product Owners were established, and agile ceremonies like daily stand-ups were introduced to enhance collaboration and transparency.

2. Contributions of Entrepreneurial Orientation in the Use of Agile Methods in Project Management

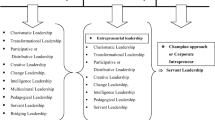

This Agile project management case study aims to analyze the degree of contribution of entrepreneurial orientation (EO) in the use of agile methods (AM) in project management. The study focuses on understanding how EO influences the adoption and effectiveness of agile methods within organizations. Through a detailed case study, we explore the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and Agile methods, shedding light on the impact of entrepreneurial behaviors on project management practices.

A technology consulting firm faced multiple challenges in project management efficiency and responsiveness to changing client requirements. This specific problem was identified because of the limited use of Agile methods in project management, which hindered the company's ability to adapt quickly and deliver optimal outcomes.

Entrepreneurial orientation (EO) is a multidimensional construct that describes the extent to which an organization engages in entrepreneurial behaviors. The technology firm acknowledged the significance of entrepreneurial orientation in promoting agility and innovation in project management.

The five dimensions of Entreprenurial orientation were applied across the organization.

- Cultivating Innovativeness: The technology consulting firm encouraged a culture of innovativeness and proactiveness, urging project teams to think creatively, identify opportunities, and take proactive measures.

- Proactiveness: Employees were empowered to generate new ideas, challenge traditional approaches, and explore alternative solutions to project challenges. This helped them to stay ahead of the competition and to deliver the best possible results for their customers.

- Encouraging Risk-Taking: The organization promoted a supportive environment that encouraged calculated risk-taking and autonomy among project teams. Employees were given the freedom to make decisions and take ownership of their projects, fostering a sense of responsibility and accountability.

- Autonomy: Agile teams were given the autonomy to make decisions and take risks. This helped them to be more innovative and to deliver better results.

- Nurturing Competitive Aggressiveness: The technology firm instilled a competitive aggressiveness in project teams, motivating them to strive for excellence and deliver superior results.

3. Improving Team Performance and Engagement

How do you ensure your team performs efficiently without compromising on quality? Agile is a way of working that focuses on value to the customer and continuous improvement. Integrating Agile in your work will not only make the team efficient but will also ensure quality work. Below is a case study that finds how agile practices can help teams perform better.

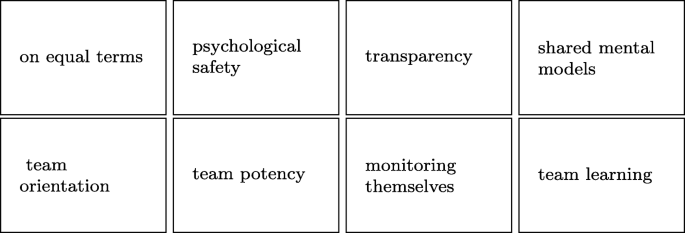

The problem addressed in this case study is the need to understand the relationship between the Agile way of working and improving team performance and engagement. We see that teams often face challenges in their daily work. It could be a slow turnover due to bad time management, compromised quality due to lack of resources, or in general lack of collaboration. In the case study below, we will understand how adopting agile practices makes teams work collaboratively, improve quality and have a customer-focused approach to work.

How it was Solved:

A number of factors mediated the relationship between agile working and team performance and engagement.

- Create a culture of trust and transparency. Agile teams need to be able to trust each other and share information openly. This will help to create a sense of collaboration and ownership. This in turn can lead to increased performance and engagement.

- Foster communication and collaboration. Effective communication within the team and with stakeholders helps everyone be on the same page.

- Empower team members. Agile teams need to be empowered to make decisions and to take risks.

- Provide regular feedback. Team members need to receive regular feedback on their performance. This helps them to identify areas where they need improvement.

- Celebrate successes. By celebrating successes, both big and small, team members are motivated. This in turn creates a positive work environment.

- Provide training and development opportunities. help the team to stay up to date on the latest trends and to improve their skills.

- Encourage continuous improvement: Promoting a culture of continuous improvement helps the team to stay ahead of the competition and to deliver better results for their customers.

It was concluded that agile ways of working can have a positive impact on employee engagement and team performance. Teams that used agile methods were more likely to report high levels of performance and engagement.

4. $65 Million Electric Utility Project Completed Ahead of Schedule and Under Budget

Xcel Energy faced a significant challenge in meeting the Reliability Need required by the Southwest Power Pool in New Mexico. The company had committed to constructing a new 34-mile, 345-kilovolt transmission line within a strict budget of $65 million and a specific timeline. Additionally, the project had to adhere to Bureau of Land Management (BLM) environmental requirements. These constraints posed a challenge to Xcel Energy in terms of project management and resource allocation.

A PM Solutions consultant with project management and utility industry experience was deployed to Xcel Energy.

The PM Solutions consultant deployed to Xcel adapted to the organization's structure and processes, integrating into the Project Management functional organization. He utilized years of project management and utility industry experience to provide valuable insights and guidance.

- Collaborative and social skills were used to address roadblocks and mitigate risks.

- Focused on identifying and addressing roadblocks and risks to ensure timely project delivery.

- Vendor, design, and construction meetings were organized to facilitate communication and collaboration.

- Monitored and expedited long-lead equipment deliveries to maintain project schedule.

- Design and Construction milestones and commitments were closely monitored through field visits.

- Actively tracked estimates, actual costs, and change orders to control project budget.

- Assisted functional areas in meeting their commitments and resolving challenges.

The project was completed eleven days ahead of schedule and approximately $4 million under budget. The management team recognized the project as a success since it went as planned, meeting all technical and quality requirements.

5. Lean product development and agile project management in the construction industry

The construction industry, specifically during the design stage, has not widely embraced Lean Project Delivery (LPD) and Agile Project Management (APM) practices. This limited adoption delays the industry's progress in enhancing efficiency, productivity, and collaboration in design.

- Integrated project delivery and collaborative contracts: Collaborative contracts were implemented to incentivize teamwork and shared project goals, effectively breaking down silos and fostering a collaborative culture within the organization.

- Lean principles in design processes: Incorporating Lean principles into design processes was encouraged to promote lean thinking and identify non-value-adding activities, bottlenecks, and process inefficiencies.

- Agile methodologies and cross-functional teams: Agile methodologies and cross-functional teams were adopted to facilitate iterative and adaptive design processes.

- Digital tools and technologies: The organization embraced digital tools and technologies, such as collaborative project management software, Building Information Modeling (BIM), and cloud-based platforms.

- A culture of innovation and learning: A culture of innovation and learning was promoted through training and workshops on Lean Project Delivery (LPD) and Agile Project Management (APM) methodologies. Incorporating Agile management training, such as KnowledgeHut Agile Training online , further enhanced the team's ability to implement LPD and APM effectively.

- Clear project goals and metrics: Clear project goals and key performance indicators (KPIs) were established, aligning with LPD and APM principles. Regular monitoring and measurement of progress against these metrics helped identify areas for improvement and drive accountability.

- Industry best practices and case studies: industry best practices and case studies were explored, and guidance was sought from experts to gain valuable insights into effective strategies and techniques for implementation.

6. Ambidexterity in Agile Software Development (ASD) Projects

An organization in the software development industry aims to enhance their understanding of the tensions between exploitation (continuity) and exploration (change) within Agile software development (ASD) project teams. They seek to identify and implement ambidextrous strategies to effectively balance these two aspects.

How it was solved:

- Recognizing tensions: Teams were encouraged to understand and acknowledge the inherent tensions between exploitation and exploration in Agile projects.

- Fostering a culture of ambidexterity: The organization created a culture that values both stability and innovation, emphasizing the importance of balancing the two.

- Balancing resource allocation: Resources were allocated between exploitation and exploration activities, ensuring a fair distribution to support both aspects effectively.

- Supporting knowledge sharing: Team members were encouraged to share their expertise and lessons learned from both exploitation and exploration, fostering a culture of continuous learning.

- Promoting cross-functional collaboration: Collaboration between team members involved in both aspects was facilitated, allowing for cross-pollination of ideas and insights.

- Establishing feedback mechanisms: Feedback loops were implemented to evaluate the impact of exploitation and exploration efforts, enabling teams to make data-driven decisions and improvements.

- Developing flexible processes: Agile practices that supported both stability and innovation, such as iterative development and adaptive planning, were adopted to ensure flexibility and responsiveness.

- Providing leadership support: Leaders promoted and provided necessary resources for the adoption of agile practices, demonstrating their commitment to ambidexterity.

- Encouraging experimentation: An environment that encouraged risk-taking and the exploration of new ideas was fostered, allowing teams to innovate and try new approaches.

- Continuous improvement: Regular assessments and adaptations of agile practices were conducted based on feedback and evolving project needs, enabling teams to continuously improve their ambidextrous strategies.

7. Problem and Solutions for PM Governance Combined with Agile Tools in Financial Services Programs

Problem: The consumer finance company faced challenges due to changing state and federal regulatory compliance requirements, resulting in the need to reinvent their custom-built storefront and home office systems. The IT and PMO teams were not equipped to handle the complexities of developing new systems, leading to schedule overruns, turnover of staff and technologies, and the need to restart projects multiple times.

How it was Solved:

To address these challenges, the company implemented several solutions with the help of PM Solutions:

- Back to Basics Approach: A senior-level program manager was brought in to conduct a full project review and establish stakeholder ownership and project governance. This helped refocus the teams on the project's objectives and establish a clear direction.

- Agile Techniques and Sprints: The company gradually introduced agile techniques, starting with a series of sprints to develop "proof of concept" components of the system. Agile methodologies allowed for more flexibility and quicker iterations, enabling faster progress.

- Expanded Use of JIRA: The company utilized Atlassian's JIRA system, which was already in place for operational maintenance, to support the new development project. PM Solutions expanded the use of JIRA by creating workflows and tools specifically tailored to the agile approach, improving timeliness and success rates for delivered work.

- Kanban Approach: A Kanban approach was introduced to help pace the work and track deliveries. This visual management technique enabled project management to monitor progress, manage workloads effectively, and report updates to stakeholders.

- Organizational Change Management: PM Solutions assisted the company in developing an organizational change management system. This system emphasized early management review of requirements and authorizations before work was assigned. By involving company leadership in prioritization and resource utilization decisions, the workload for the IT department was reduced, and focus was placed on essential tasks and priorities.

8. Insurance Company Cuts Cycle Time by 20% and Saves Nearly $5 Million Using Agile Project Management Practices

In this Agile Scrum case study, the insurance company successfully implemented Agile Scrum methodology for their software development projects, resulting in significant improvements in project delivery and overall team performance.

The insurance company faced challenges with long project cycles, slow decision-making processes, and lack of flexibility in adapting to changing customer demands. These issues resulted in higher costs, delayed project deliveries, and lower customer satisfaction levels.

- Implementation of Agile Practices: To address these challenges, the company decided to transition from traditional project management approaches to Agile methodologies. The key steps in implementing Agile practices were as follows:

- Executive Sponsorship: The company's leadership recognized the need for change and provided full support for the Agile transformation initiative. They appointed Agile champions and empowered them to drive the adoption of Agile practices across the organization.

- Training and Skill Development: Agile training programs were conducted to equip employees with the necessary knowledge and skills. Training covered various Agile frameworks, such as Scrum and Kanban, and focused on enhancing collaboration, adaptive planning, and iterative development.

- Agile Team Formation: Cross-functional Agile teams were formed, consisting of individuals with diverse skill sets necessary to deliver projects end-to-end. These teams were self-organizing and empowered to make decisions, fostering a sense of ownership and accountability.

- Agile Project Management Tools: The company implemented Agile project management tools and platforms to facilitate communication, collaboration, and transparency. These tools enabled real-time tracking of project progress, backlog management, and seamless coordination among team members.

9. Agile and Generic Work Values of British vs Indian IT Workers

Problem:

In this Agile transformation case study, the problem identified is the lack of effective communication and alignment within an IT firm unit during the transformation towards an agile work culture. The employees from different cultural backgrounds had different perceptions and understanding of what it means to be agile, leading to clashes in behaviors and limited team communication. This situation undermined morale, trust, and the sense of working well together.

The study suggests that the cultural background of IT employees and managers, influenced by different national values and norms, can impact the adoption and interpretation of agile work values.

- Leadership: Leaders role-modeled the full agile mindset, along with cross-cultural skills. They demonstrated teamwork, justice, equality, transparency, end-user orientation, helpful leadership, and effective communication.

- Culture: Managers recognized and appreciated the cultural diversity within the organization. Cultural awareness and sensitivity training were provided to help employees and managers understand and appreciate the diverse cultural backgrounds within the organization.

- Agile values: The importance of agile work values was emphasized, including shared responsibility, continuous learning and improvement, self-organizing teamwork, fast fact-based decision-making, empowered employees, and embracing change. Managers actively promoted and reinforced these values in their leading and coaching efforts to cultivate an agile mindset among employees.

- Transformation: A shift was made from a centralized accountability model to a culture of shared responsibility. Participation in planning work projects was encouraged, and employees were empowered to choose their own tasks within the context of the team's objectives.

- Roadmap: An agile transformation roadmap was developed and implemented, covering specific actions and milestones to accelerate the adoption of agile ways of working.

- Senior management received necessary support, training, and additional management consultancy to drive the agile transformation effectively.

Benefits of Case Studies for Professionals

Case studies provide several benefits for professionals in various fields:

- Real-world Application: Agile methodology examples and case studies offer insights into real-life situations, allowing professionals to see how theoretical concepts and principles are applied in practice.

- Learning from Success and Failure: Agile transformation case studies often present both successful and failed projects or initiatives. By examining these cases, professionals can learn from the successes and avoid the mistakes made in the failures.

- Problem-solving and Decision-making Skills: Case studies present complex problems or challenges that professionals need to analyze and solve. By working through these cases, professionals develop critical thinking, problem-solving, and decision-making skills.

- Building Expertise: By studying cases that are relevant to their area of expertise, professionals can enhance their knowledge and become subject matter experts.

- Professional Development: Analyzing and discussing case studies with peers or mentors promotes professional development.

- Practical Application of Concepts: Teams can test their understanding of concepts, methodologies, and best practices by analyzing and proposing solutions for the challenges presented in the cases.

- Continuous Learning and Adaptation: By studying these cases, professionals can stay updated on industry trends, best practices, and emerging technologies.

Examine the top trending Agile Category Courses

In conclusion, agile methodology case studies are valuable tools for professionals in various fields. The real-world examples and insights into specific problems and solutions, allow professionals to learn from others' experiences and apply those learning their own work. Case studies offer a deeper understanding of complex situations, highlighting the challenges faced, the strategies employed, and the outcomes achieved.

The benefits of case studies for professionals are numerous. They offer an opportunity to analyze and evaluate different approaches, methodologies, and best practices. Case studies also help professionals develop critical thinking skills, problem-solving abilities, and decision-making capabilities through practical scenarios and dilemmas to navigate.

Overall, agile case study examples offer professionals the opportunity to gain practical wisdom and enhance their professional development. Studying real-life examples helps professionals acquire valuable insights, expand their knowledge base, and improve their problem-solving abilities.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Three examples of Agile methodologies are:

Scrum: Scrum is one of the most widely used Agile frameworks. It emphasizes iterative and incremental development, with a focus on delivering value to the customer in short, time-boxed iterations called sprints.

Kanban: Kanban is a visual Agile framework that aims to optimize workflow efficiency and promote continuous delivery.

Lean: Lean is a philosophy and Agile approach focused on maximizing value while minimizing waste.

- People over process: Agile values the people involved in software development, and emphasizes communication and collaboration.

- Working software over documentation: Agile prioritizes delivering working software over extensive documentation.

- Customer collaboration over contract negotiation: Agile values close collaboration with customers and stakeholders throughout the development process.

- Responding to change over following a plan: Agile recognizes that change is inevitable, and encourages flexibility and adaptability.

The six phases in Agile are:

- Initiation: Define the project and assemble the team.

- Planning: Create a plan for how to achieve the project's goals.

- Development: Build the product or service in short sprints.

- Testing: Ensure the product or service meets requirements.

- Deployment: Release the product or service to the customer.

- Maintenance: Support the product or service with bug fixes, new features, and improvements.

Lindy Quick

Lindy Quick, SPCT, is a dynamic Transformation Architect and Senior Business Agility Consultant with a proven track record of success in driving agile transformations. With expertise in multiple agile frameworks, including SAFe, Scrum, and Kanban, Lindy has led impactful transformations across diverse industries such as manufacturing, defense, insurance/financial, and federal government. Lindy's exceptional communication, leadership, and problem-solving skills have earned her a reputation as a trusted advisor. Currently associated with KnowledgeHut and upGrad, Lindy fosters Lean-Agile principles and mindset through coaching, training, and successful execution of transformations. With a passion for effective value delivery, Lindy is a sought-after expert in the field.

Avail your free 1:1 mentorship session.

Something went wrong

Upcoming Agile Management Batches & Dates

Product Management

Product Development

Product Capability

- Client Stories

- Agile Delivery

Agile at Scale: Insights From 42 Real-World Case Studies

Even though most large teams are already on an agile journey, many are still looking for how to make agile work at scale. There is no shortage of opinions available, including my own, but I wanted to get deeper than just opinion and look at what the independent research says.

One of the more thorough and comprehensive research papers I found was an aggregation of 42 real-world studies into making agile at scale work. The paper is Challenges and success factors for large-scale agile transformations: A systematic literature review from 2016 authored by Kim Dikert, Maria Paasivaara and Casper Lassenius from MIT and the Aalto University in Finland.

Agile has reached the plateau of productivity where teams need to focus on incremental improvements to how they run agile. So, the insights from a paper like this provide an interesting lens to diagnose problems and make those incremental improvements.

In this post, you will get an overview of the insights from the paper:

- 35 challenges organised into 9 Challenge Areas

- 29 success factors organised into 9 Success Factor Areas

What Insights Were the Strongest

The list of challenges and success factors is 64 items long and worth going through in detail but to save you some time, here is a brief overview of the factors that the researchers deemed the strongest.

The Challenge Areas that came through strongest:

- Agile being difficult to implement (48% of studies),

- Integrating non-development functions (43%),

- Change resistance (38%) and Requirements engineering challenges (38%).

The Success Factor Areas that came through the strongest:

- Choosing and customising the agile approach (50%),

- Management support (40%),

- Mindset and Alignment (40%),

- Training and coaching (38%).

Challenge Areas for Agile at Scale

There are a number of challenges that you, your team and your organisation will face in making agile work at scale. Many of the challenges identified by the research will likely resonate with you.

This list can be helpful in debugging and articulating the problem you are facing. The Challenge Areas are:

- Change resistance

- Lack of investment

- Agile being difficult to implement

- Coordination challenges in multi-team environments

- Different approaches emerge in a multi-team environment

- Hierarchical management and organisational boundaries

- Requirements engineering challenges

- Quality assurance challenges

- Integrating non-development functions in the transformation

Each of these is expanded out below into more specific challenges.

1. Change Resistance

People are inherently resistant to change. Here are some of the specific challenges around resistance to change when it comes to agile at scale:

- General resistance to change

- Scepticism towards the new way of working

- Top-down mandate creates resistance

- Management unwilling to change

2. Lack of Investment

Making agile work requires some investments. A lack of investment in some specific areas is a challenge to making agile at scale work:

- Lack of coaching

- Lack of training

- Too high workload

- Old commitments kept

- Challenges in rearranging physical spaces

3. Agile Being Difficult to Implement

There are some difficulties specific to agile itself:

- Misunderstanding agile concepts

- Lack of guidance from the literature

- Agile customised poorly

- Reverting to the old way of working

- Excessive enthusiasm

4. Coordination Challenges in Multi-team Environments

There are some challenges specific to coordinating across multiple teams:

- Interfacing between teams is difficult

- Autonomous team model is challenging

- Global distribution challenges

- Achieving technical consistency

5. Different Approaches Emerge in a Multi-Team Environment

When you’re doing agile at scale, different approaches emerge which present these challenges:

- Interpretation of agile differs between teams

- Using old and new approaches side by side

6. Hierarchical Management and Organisational Boundaries

The organisation’s structure presents some challenges:

- Middle managers role in agile unclear

- Management is in waterfall mode

- Keeping the old bureaucracy

- Internal silos kept

7. Requirements Engineering Challenges

At scale, requirements in agile present some challenges:

- High-level requirements management largely missing in agile

- Requirement refinement challenging

- Creating and estimating user stories hard

- The gap between long and short term planning

8. Quality Assurance Challenges

Making agile work at scale means facing some challenges around quality:

- Accommodating non-functional testing

- Lack of automated testing

- Requirements ambiguity affects QA

9. Integrating Non-Development Functions in the Transformation

Once agile starts to move beyond the development team, which is inevitable at scale, then there are some challenges in involving other parts of the organisation:

- Other functions unwilling to change

- Challenges in adjusting to incremental delivery pace

- Challenges in adjusting product launch activities

- Rewarding model, not teamwork centric

Success Factor Areas for Agile at Scale

The research identified 29 factors that can help make agile work better at scale and grouped them into these top-level areas:

- Management support

- Commitment to change

- Choosing and customising the agile approach

- Training and coaching

- Engaging people

- Communication and transparency

- Mindset and Alignment

- Team autonomy

- Requirements management

1. Management Support

Management support is a key part of agile succeeding at scale. The individual factors are:

- Ensure management support.

- Make management support visible

- Educate management on agile

2. Commitment to Change

Agile needs a commitment to change, specifically:

- Communicate that change is non-negotiable

- Show strong commitment

3. Leadership

Leaders can play a role in success. The factors at play here are:

- Recognise the importance of change leaders

- Engage change leaders without the baggage of the past

4. Choosing and Customising the Agile Approach

There are some specifics to how you customise agile that can set you up for success:

- Customise the agile approach carefully

- Conform to a single approach

- Map to the old way of working to ease adaptation

- Keep it simple

5. Piloting

A pilot can help agile succeed, specifically:

- Start with a pilot to gain acceptance

- Gather insights from a pilot

6. Training and Coaching

There are two key success factors when it comes to upskilling your people and teams for agile at scale:

- Provide training on agile methods

- Coach teams as they learn by doing

7. Engaging People

People play a key role in making agile work at scale. The specific factors around engaging people in the journey are:

- Start with agile supporters

- Include persons with previous agile experience

- Engage everyone

8. Communication and Transparency

There are some success factors for communicating:

- Communicate the change intensively

- Make the change transparent

- Create and communicate positive experiences in the beginning

9. Mindset and Alignment

The success factors for agile around mindset and alignment are:

- Concentrate on agile values

- Arrange social events

- Cherish agile communities

- Align the organisation

10. Team Autonomy

Team autonomy has two factors that enable success with agile:

- Allow teams to self-organize

- Allow grassroots level empowerment

11. Requirements Management

There are also two factors when managing requirements that can help enable agile at scale:

- Recognise the importance of the product owner role

- Invest in learning to refine the requirements

More on Agile:

- Simple View of Common Elements of Agile at Scale

- Video: Agile is Dead, McKinsey Just Killed It

Scott Middleton CEO & Founder

Scott has been involved in the launch and growth of 61+ products and has published over 120 articles and videos that have been viewed over 120,000 times. Terem’s product development and strategy arm, builds and takes clients tech products to market, while the joint venture arm focuses on building tech spinouts in partnership with market leaders.

Twitter: @scottmiddleton LinkedIn: linkedin.com/in/scottmiddleton

Get articles like this sent to your inbox and build better products

- Agile Education Program

- The Agile Navigator

Agile Unleashed at Scale

How john deere’s global it group implemented a holistic transformation powered by scrum@scale, scrum, devops, and a modernized technology stack, agile unleashed at scale: results at a glance, executive summary.

In 2019 John Deere’s Global IT group launched an Agile transformation with the simple but ambitious goal of improving speed to outcomes.

As with most Fortune 100 companies, Agile methodologies and practices were not new to John Deere’s Global IT group, but senior leadership wasn’t seeing the results they desired. “We had used other scaled frameworks in the past—which are perfectly strong Agile processes,” explains Josh Edgin, Transformation Lead at John Deere, “But with PSI planning and two-month release cycles, I think you can get comfortable transforming into a mini-waterfall.” Edgin adds, “We needed to evolve.”

Senior leadership decided to launch a holistic transformation that would touch every aspect of the group’s work – from application development to core infrastructure; from customer and dealer-facing products to operations-oriented design, manufacturing and supply chain, and internal/back-end finance and human resource products.

Picking the right Agile framework is one of the most important decisions an organization can make. This is especially true when effective scaling is a core component of the overall strategy. “Leadership found the Scrum@Scale methodology to be the right fit to scale across IT and the rest of the business,” states Ganesh Jayaram, John Deere’s Vice President of Global IT. Therefore, the Scrum and Scrum@Scale frameworks, entwined with DevOps and technical upskilling became the core components of the group’s new Agile Operating Model (AOM).

Picking the right Agile consulting, training, and coaching support can be just as important as the choice of framework. Scrum Inc. is known for its expertise, deep experience, and long track record of success in both training and large and complex transformations. Additionally, Scrum Inc. offered industry-leading on-demand courses to accelerate the implementation, and a proven path to create self-sustaining Agile organizations able to successfully run their own Agile journey.

“I remember standing in front of our CEO and the Board of Directors to make this pitch,” says Jayaram, “because it was the single largest investment Global IT has made in terms of capital and expense.” But the payoff, he adds, would be significant. “We bet the farm so to speak. We promised we would do more, do it faster, and do it cheaper.”

John Deere’s CEO gave the transformation a green light.

Just two years into the effort it is a bet that has paid off.

Metrics and Results

Enterprise-level results include:

- Return on Investment: John Deere estimates its ROI from the Global IT group’s transformation to be greater than 100 percent .

- Output: Has increased by 165 percent , exceeding the initial goal of 125 percent.

- Time to Market: Has been reduced by 63 percent — leadership initially sought a 40 percent reduction.

- Engineering Ratio: When looking at the complete organizational structure of Scrum Masters, Product Owners, Agile Coaches, Engineering Managers, UX Professionals, and team members, leadership set a target of 75% with “fingers on keyboards” delivering value through engineering. This ratio now stands at 77.7 percent .

- Cost Efficiency: Leadership wanted to reduce the labor costs of the group by 20 percent . They have achieved this goal through insourcing and strategic hiring–even with the addition of Scrum and Agile roles.

- Employee NPS (eNPS): Employee Net Promoter Score, or eNPS, is a reflection of team health. The Global IT group began with a 42-point baseline. A score above 50 is considered excellent. The group now has a score of 65 , greater than the 20-point improvement targeted by leadership.

John Deere’s Global IT group has seen function/team level improvements that far exceed these results. Order Management, the pilot project for this implementation has seen team results which include:

- The number of Functions/Features Delivered per Sprint has increased by more than 10X

- The number of Deploys has improved by more than 15X

As Jayaram notes, “When you look at some of the metrics and you see a 1,000 percent improvement you can’t help but think they got the baseline wrong.”

But the baselines are right. The improvement is real.

John Deere’s Global IT group has also seen exponential results thanks to the implementation of the AOM. “We’ve delivered an order of magnitude more value and bottom-line impact to John Deere in the ERP space than in any previous year,” states Edgin. These results include:

- Time to Market: Reduced by 87 percent

- Deploys: Increased by 400 percent

- Features/Functions Delivered per Sprint: Has nearly tripled

Edgin adds that “every quality measure has improved measurably. We’re delivering things at speeds previously not thought possible. And we’re doing it with fewer people.”

Training at Scale and Creating a Self-Sufficient Agile Organization

The Wave/Phase approach has ensured both effective and efficient training across John Deere’s Global IT group. As of December 2021, roughly 24-months after its inception:

- 295 teams have successfully completed a full wave of training

- Approximately 2,500 individuals have successfully completed their training

- 50 teams were actively in wave training

- Approximately 150 teams were actively preparing to enter a wave

John Deere’s Global IT group is well on its way to becoming a self-sustaining Agile organization thanks to its work with Scrum Inc.

- Internal training capacity increased by 64 percent over a two-year span

- The number of classes led by internal trainers doubled (from 25 to 50) between 2020 and 2021

Click on the Section Titles Below to Read this I n-Depth Case Study

1. introduction: the complex challenge to overcome.

This need can be unlocking innovation, overcoming a complex challenge, more efficient and effective prioritization, removing roadblocks, or the desire to delight customers through innovation and value delivery.

Ganesh Jayaram is John Deere’s Vice President of Global IT. He summarizes the overarching need behind this Agile transformation down to a simple but powerful four-word vision; improve speed to outcomes.

Note this is not going fast just for the sake of going fast – that can be a recipe for unhappy customers and decreased quality. Very much the opposite of Agile.

Dissect Jayaram’s vision, and you’ll find elements at the heart of Agile itself; rapid iteration, innovation, quality, value delivery, and most importantly, delighted customers. Had John Deere lost sight of these elements? Absolutely not.

As Jayaram explains, “we intended to significantly improve on delivering these outcomes.” To do this, Jayaram and his leadership team decomposed their vision of ‘improve speed to outcomes’ into three enterprise-level goals:

- Speed to Understanding: How would they know they are truly sensitive to what their customers – both internal and external – care about, want, and need?

- Speed to Decision Making: Decrease decision latency to improve the ability to capitalize on opportunities, respond to market changes, or pivot based on rapid feedback.

- Speed to Execution: Decrease time to market while maintaining or improving quality and value delivery.

Deere’s Global IT leadership knew achieving their vision and these goals would take more than incremental adjustments. Beneficial change at this level requires a holistic transformation that spans the IT group as well as the business partners.

They needed the right Agile transformation support, the ability to efficiently and effectively scale both training and operations and to build the in-house expertise to make the group’s Agile journey a self-sustaining one. As Josh Edgin, Global IT Transformation Lead at John Deere states, “We needed to evolve.”

2. Background: The Transformation's Ambitious Goals

Before this transformation, John Deere’s Global IT function operated like that of many large organizations. In broad terms, this meant that:

- The department had isolated pockets of Agile teams that implemented several different Agile frameworks in an ad hoc way

- Teams were often assigned to projects which were funded for a fixed period of time

- The exact work to be done on projects was dictated by extensive business analysis and similar plans

- Outsourcing of projects or components to third-party suppliers was commonplace

- The manager role was largely comprised of primarily directing and prioritizing work for their teams

At John Deere, process maturity was very high. Practices such as these were created in the Second Industrial Revolution and they can deliver value, especially if you have a defined, repeatable process. However, if you have a product or service that needs to evolve to meet changing market demands, these legacy leadership practices can quickly become liabilities.

- Pockets of Agile can deliver better results. But isolated Agile teams will inherently be dependent on non-Agile teams to deliver value. This limits the effectiveness and productivity gains of Agile teams specifically and the organization as a whole. The ad hoc use of different Agile frameworks, as Vice President Jayaram explains, compounds this problem by “not being something we could replicate and scale across the organization.”

- Project-oriented teams are often incentivized to deliver only what the project plan calls for – this inhibits a customer-centric mindset and the incorporation of feedback.

- Expecting teams to always stick to a predetermined plan limits their ability to innovate, creatively problem solve, or pivot to respond to changing requirements or market conditions.

- Outsourcing can create flexibility for organizations, but an over-reliance on outsourcing can slow speed to market and value delivery.

- Too many handoffs deliver little if any value. These can also significantly slow progress on any project or product which increases time to market.

- IT managers that are primarily delegators can become a form of overhead since they’re not actively producing value for customers. Their other skills can atrophy leaving them ill-equipped to help develop their team members, and overall team member engagement and talent retention can suffer.

2.1 The Transformation Goal

Improving speed to outcomes required greater employee engagement, decreased time to market, higher productivity, better prioritization, and alignment, and increase the engineering ratio – the percentage of the organization with what Jayaram and Edgin call “fingers on keyboards” who create the products customers used.

Additionally, leadership wanted to increase the group’s in-house technical expertise, modernize its technology stack, unify around a single Agile framework that easily and efficiently scaled both across IT and the rest of the business, and reorganize its products and portfolios around Agile value streams. All while meeting or exceeding current quality standards.

Leadership wanted to go big. They wanted nothing less than a holistic Agile transformation that would improve every aspect of their business and all of the group’s 500 teams.

Next, senior leadership created the group-wide metrics they would use to measure success. These included:

- Output: Increase by 125 percent

- Time to Market: Reduce by 40 percent

- Engineering Ratio: Improve to 75 percent with “fingers on keyboards”

- Employee NPS (eNPS): 20-point improvement

- Cost Efficiency: They would reduce labor costs by 20 percent

At the time, these goals seemed ambitious to say the least. “I remember standing in front of our CEO and the Board of Directors to make this pitch,” says Jayaram, “because it was the single largest investment Global IT has made in terms of capital and expense.” But the payoff, he adds, would be significant. “We bet the farm so to speak. We promised we would do more, do it faster, and do it cheaper.”

John Deere’s CEO gave the transformation, called the Agile Operating Model (AOM), a green light.

3. Agile Operating Model: Why John Deere Chose Scrum And Scrum@Scale

Picking the right Agile framework is one of the most important decisions an organization can make. This is especially true when effective scaling is a core component of the overall strategy.

As Edgin explains, Agile was not new to John Deere’s Global IT group. “We had Agile practices. We had Agile teams. We were delivering value.”

But says Edgin, they weren’t satisfied with the results. So, a team began evaluating several different Agile methodologies. They examined what had been done at John Deere in the past and anticipated what the group’s future needs would be.

In the past, Edgin states, “We had used other scaled frameworks—which are perfectly strong Agile processes. But with PSI planning and two-month release cycles, I think you can get comfortable transforming into a mini-waterfall,” he says, “So we aligned on Scrum being the best fit for our culture and what we wanted to accomplish.”

Early on, leadership decided to implement a tight partnership where the IT delivery team(s) are closely coupled with the product organization that is the voice of the customer. When connecting multiple products together, “leadership found the Scrum@Scale methodology to be the best fit to scale across IT and the rest of the business,” says Jayaram.

The Scrum and Scrum@Scale frameworks, entwined with DevOps and technical upskilling, became integral Agile components of the group’s new AOM.

4. The Foundry: More Than A Training Facility

When it came time to name the final and arguably most important component of the AOM, the Foundry was a clear choice. It recognizes the company’s proud heritage while also symbolizing the change that would drive the Global IT group into the future.

Many organizations incorporate a “learning dojo model” when implementing an Agile transformation. These dojos and their teams are often home to Agile practices, conduct training sessions, and provide immersive coaching for newly launched Agile teams.

Training is, of course, a critical piece of any transformation. As is coaching. After all, switching from a traditional command and control approach to an Agile servant leader approach is a significant, sometimes disorienting change.

However, some corporate dojos work on what could be considered a “catch and release” strategy. They provide one or two weeks of baseline Agile training to individuals and teams, then say “get to it”. Coaching is limited and provided primarily by outside consultants.

The first problem with “catch and release” dojos is the cookie-cutter-like approach. A mass “baseline only” training strategy focus on volume — not understanding and usability.

The second problem is the over-reliance on outside consultants for team and organizational coaching. The cost-prohibited nature of outside consultants can limit the levels of coaching each team receives. This approach also equates to an organization outsourcing its Agile knowledge base and thought leadership — a critical competency in modern business.

The John Deere Foundry and Deere’s approach to embedding Agile Coaches and Scrum Masters across the organization represents the evolution of the dojo model by addressing these problems head-on.

4.1 A Relationship Built on Creating a Self-Sustaining Agile Organization

From the beginning, John Deere’s relationship with Scrum Inc. was built around creating a self-sustaining Agile organization. One where the Foundry’s own internal trainers and coaches would build all the capabilities they needed to ensure the Global IT group’s Agile transformation was a self-sustaining one.

This included not just materials needed to train new Agile teams. This relationship included sharing all the knowledge, skills, expertise, content, and tactics critical to training the coaches and trainers themselves.

The Foundry was launched by a dedicated team comprised of both John Deere’s internal trainers and coaches and their Scrum Inc. counterparts. They worked from a single backlog which prioritized knowledge sharing along with the “hands-on” work of training John Deere’s Global IT teams in Scrum.

Scrum Inc.’s consultants took leading roles during the first wave of training, while their John Deere counterparts observed and learned the content and techniques. By the third wave, John Deere’s internal trainers and coaches were taking the lead, with Scrum Inc.’s consultants there to advise and refine the program.

As time passed, a significant number of trainers and coaches inside the Foundry and across the organization showed the level of mastery needed to successfully pass Scrum Inc.’s intensive Registered Scrum Trainer and Registered Agile Coach courses. They could now credential their own students. More importantly, they demonstrated the ability to drive the Global IT group’s Agile transformation forward on their own.

This approach removes any reliance on outside contractors for key competencies.

4.2 Unified, Context-Specific Training

Implementing an Agile transformation is a complex challenge. Research continues to show that ineffective or insufficient levels of training and coaching are leading causes of failed implementations. So too are misalignment, misunderstandings, or outright misuse of the concepts and terminology important to any Agile framework.

In short, everyone needs to share a unified understanding of the new way of working for it to have any chance of working at all.

The best way to overcome the problem of a cookie-cutter approach is to ensure all training content is as context-specific as possible.

Here too the connection between the Foundry and Scrum Inc. was important.

The joint team of John Deere and Scrum Inc. staff swarmed to create Agile courses packed with customized, context-specific material that would resonate with the company’s Global IT group.

This content removed any feeling of a cookie-cutter approach and increased the usability of each lesson.

4.3 Results

- Internal training capacity increased by 64 percent over a two-year span

- John Deere trainers are now leading customized, context-specific courses including Scrum Master , Product Owner , Engineering Manager , Agile for Leaders , Scrum@Scale Practitioner , and Scrum@Scale Foundations

Perhaps the best measure of success is the waiting list of teams wanting to go through Agile training and coaching. Initially, hesitancy over implementing the Agile Operating Model and undergoing training was high. Initially, there wasn’t a high demand for the training, however as early adopters experienced success, demand for the training grew. Soon teams were actively seeking admission to the next planned cohort. Now, even with greatly expanded capacity, there is a waiting list.

The Foundry model has been so successful that John Deere’s Global IT group has expanded its footprint to include coaching in Mexico, Germany, and Brazil and launched a full-scale Foundry program at the company’s facility in India. In addition to the Foundry, embedded Agile coaches continuing to drive transformation locally are a key component to the model’s success.

5. How To Achieve Efficient and Effective Training at Scale

Enter the Wave/Phase training approach implemented by the Foundry with Scrum Inc.

In this model, each team includes IT engineers along with their Scrum Masters and business-focused Product Owners. A training cohort, usually comprised of 40 to 50 teams, constitutes a wave.

The waves themselves are comprised of three distinct phases:

- The Pre-Phase: Where teams and locally embedded agile coaches prepare for an immersive wave coaching experience

- The Preparation Phase: Focuses on product organization and customer journeys

- The Immersion Phase: Team launch, coaching, and full immersion into the AOM

All three phases are designed to run concurrently, which keeps the pipeline full, flowing, and ensures efficient training at scale. The transformation doesn’t end with the wave experience. Continuous improvement and ongoing transformation continue well beyond the Immersion Phase, led by embedded agile leaders in partnership with The Foundry.

The quality and context-specific nature of the training itself, along with the “left-seat-right-seat” nature of the coaching, ensures the learning is effective.

5.1 The Pre-Phase

Embedded Agile coaches are continuously transforming teams in their organizations even before they enter a wave. One goal of the Pre-Phase is to ensure readiness of teams looking to enter a wave. Acceptance criteria include:

- Proper organization design review to ensure teams are set up to succeed with the correct roles

- A draft plan for their product structure (explained in more detail in section 6 of this case study)

- The Scrum Roles of Product Owner, Engineering Manager, and Scrum Master are filled

Ryan Trotter is a principal Agile coach with more than 25 years of experience in various capacities at John Deere. Trotter says experience shows that not meeting one or more criteria “causes deeper conversations and could result in some mitigations or delaying until they’re ready.”

5.2 The Preparation Phase

The benefits of an Agile mindset and processes can be significantly limited by legacy structures.

Therefore, product organization is the primary focus of the preparation phase.

“We want to create a much stronger connection between the customer, and the Product Owner and team” explains Heidi Bernhardt who has been a senior leader of the Agile Operating Model since its inception. Bernhardt has been with John Deere for more than two decades now. She says individuals in the product and portfolio side of the house learn to “think in a different way.”

Participants in the preparation phase learn how to create customer journey maps and conduct real-world customer interviews to ensure their feedback loops are both informative and rapid — key drivers of success for any Scrum team and organization explains Bernhardt, “They’re talking with the customer every Sprint, asking what their needs are and what they anticipate in the future.”

They also learn how to manage and prioritize backlogs and how to do long-term planning in an Agile way.

Scrum Role training is a critical component of the preparation phase. Product Owners and Scrum Masters attend both Registered Scrum Master and Registered Product Owner courses.

Team members and others who interact regularly with the team take Scrum Startup for Teams , a digital, on-demand learning course offered by Scrum Inc. “Scrum Startup for Teams provides a really good base level of understanding,” says Ryan Trotter, “People can take it at their own pace and they can go back and review it whenever they want. It really hit a sweet spot for our software engineers.”

By the end of 2021 Scrum Startup for Teams had helped train roughly 2,500 people in the Global IT group and nearly the same number of individuals throughout the rest of John Deere — including those who aren’t on Scrum Teams but who work closely with them.

5.3 The Immersion Phase

The 10-week long immersion phase is where the Agile mindset and the AOM take flight. Where the Scrum and Scrum@Scale frameworks are fully implemented and the teams turn the concepts they’ve learned in the prior phases into their new way of working.

For John Deere’s Global IT group, immersion is not a theoretical exercise. It is not downtime. It is on-the-job training in a new way of working that meets each team at their current maturity level.

The first week of immersion is the only time teams aren’t dedicated to their usual duties.

During this time, says Trotter, coaches and trainers are reinforcing concepts, answering questions, and the teams are working through a team canvas. “This is where the team members identify their purpose, their product, and agree on how they’ll work together.”

Teams are fully focused on delivering value and their real-world product over the next nine weeks.

The Product Owner sets the team’s priorities, refines the backlog, and shares the customer feedback they’ve gathered. The Scrum Master helps the team continuously improve and remove or make impediments visible. Scrum Masters collaborates with an embedded Agile Coach that continues to champion transformation. Team members are delivering value. John Deere’s technical coach for the team is the Engineering Manager, a role that has transformed from the original team leader.

Those in the immersion phase receive intensive coaching, but they are also empowered to innovate or creatively problem solve on their own. The goal is for the coaches to help make agility and learning through experimentation a part of each team’s DNA.

The transition from students to practitioners becomes more apparent towards the end of immersion. Coaches take more of a back seat in the process explains Trotter. “We don’t want to create a false dependency. We want the teams to take ownership of their own Agile journey, to know the Foundry is here when needed but to be confident that they’ve got this and can run with it so they can continuously improve on their own.”

5.4 Measuring Wave Training Effectiveness

Measuring the effectiveness of any large-scale Agile training program requires more than just counting the number of completed courses or credentials received. The instructors and coaches must be able to see the Agile mindset has also taken hold and the implementation is making a positive impact on the organization. They also need the ability to see where problems are arising so they can provide additional coaching, training, and other resources where needed.

John Deere’s internal coaches created their Ten Immersion Principles (TIPS) as a way of measuring team health once they leave the immersion phase. Foundry coaches and trainers can then focus their efforts to create a continuous learning backlog that the team owns.

The TIPS are:

- Value Flows Through the System Super Fast: The team can deliver new products or features to customers very quickly. Any impediments or dependencies hindering delivery are quickly identified and addressed

- Amplify Feedback Loops: Rapid feedback from customers is a reality

- Continuous Learning Organization: The team is taking ownership of their learning paths and Agile journey

- Deliver Value in Small Increments: The team delivers value to customers in small pieces in order to gather feedback, test hypotheses, and pivot if needed

- Customer Centricity: The team is focused on those actually using the product and not just the stakeholders interested in the value the product should deliver

- Continuous Improvement: The team is always looking for ways to improve product and process

- Big and Visible: The team make progress, impediments, and all needed information transparent and easy to find

- Team is Predictable: The team tracks productivity metrics and estimates backlog items so that the anticipated date of delivery for products or features can be known

- Data-Driven Decisions: Feedback and real data, not the loudest voice or squeaky wheel — is used to make decisions

- Culture of Experimentation: The team is willing to take calculated risks and are able to learn from failure

5.5 Results

The positive business impact this training has had is outlined in section 8. Metrics and Results of this case study.

6. Agile Product and Portfolio Management: Why It's Important And How To Do It

Erin Wyffels keeps an old whiteboard in her office as a reminder of the moment she and her team solved a particularly complex problem.

Wyffels leads the product excellence area of the Foundry, supporting John Deere’s product leaders in product ownership and the dynamic portfolio process. She has a long history with traditional project management, inside and outside of IT. Over the past two years, she has grown her expertise in Agile product and portfolio management.

John Deere’s Global IT group manages a catalog of more than 400 digital products across 500 teams. These support every business capability in the broader company — from finance and marketing to manufacturing and infrastructure and operations.

Most large organizations are built on legacy systems. Left unchanged, these systems can limit the effectiveness of an Agile transformation. Wyffels says the prior structure of projects and portfolios within John Deere’s Global IT group was just such a system. “Our old taxonomy would in no way work with Agile.” So, she was picked to help change it for the better.

6.1 Why the Product and Portfolio Structure Needed to Change

Before implementing the AOM, portfolio management was an annual affair. One that Wyffels says, “left everyone unhappy.”

Stakeholders and senior leadership would come with a list of desired projects. Financial analysts, IT department managers, and portfolio managers would then hash out funding for these projects. Teams would then be assigned to the resourced projects. All pretty standard stuff in the corporate world.

There are, however, several problems with this approach.

Take the focus on projects. Traditional project management is a very effective approach for defined processes. By definition, a project has a start date and an end date. A set amount of work is to be done at a predetermined cost.

The weakness in traditional project management becomes apparent when you have a product or service that will evolve and emerge over time. There are just too many unknowns for the traditional approach to work effectively.

Then there’s the time it takes to make decisions based on customer feedback. As Wyffels points out, the annual nature of the pre-AOM process meant, “The best information and data you could get would be a quarter old.” Agility requires far more rapid feedback loops.

Throw in a taxonomy built more around project type than the value delivered and employees who were moved to projects instead of allowed to own a product end-to-end, and John Deere’s Global IT group had a system that was optimized based on constraints but didn’t support where the company was headed next. They were ready for a system that promoted total product ownership including value, investment, and quality and move to the next level of product maturity.

6.2 Customer Perspective and Value Streams

The need to adopt Agile product and portfolio management processes became apparent early in the AOM’s implementation.

Amy Willard is a Group Engineering Manager currently leading the AOM Foundry. She says this also becomes apparent for individual teams taking part in the immersion phase of wave training. “We see changes in their product structure evolving. They have that aha moment and realize the structure we had before wasn’t quite right.”

The new, Agile structure focuses on three critical components — customer perspective, value streams, and a product mindset.

- Customer Perspective: Willard says the value delivered to customer personas is now used to more logically group products and product families. This Agile taxonomy helps to reduce time to market and boost innovation by fostering greater coordination and collaboration between teams.

- Value Streams: Dependencies, handoffs, and removing bottlenecks are also considered when creating product groups and portfolios. Willard notes, “We’ve had a lot of success with developing value stream maps across products,” also from a customer journey perspective.

- Product Mindset: Projects are defined by their scope, cost, and duration. Products are different, they evolve based on market feedback to continually deliver value to customers. The difference may sound small, but Willard says it represents a “major shift” in mindset for the Global IT group.

The group has developed a curriculum for people in product roles in each transformation wave, with coaching support available to each person. The same content has been made available for all roles through a self-learning option, which is great for non-product roles or people that take a new position after their group’s wave is complete. Additionally, the communities being established for product roles and collaboration across people in the roles are the final building blocks to continued maturity after the transformation waves are done.

6.3 Highlighted Result: Better Value-Based Investments

The implementation of Agile product and portfolio management has yielded numerous positive results for John Deere’s Global IT group. These structural changes were critical drivers of the success noted in the Metrics and Results section of this case study.

This shift has also increased the ability of the group’s senior leadership to act like venture capitalists and invest resources into areas and products with the most potential value to both the organization and customers.

All products are now segmented into one of three categories based on actual value delivery and market feedback. These categories are:

- Grow: High-value products or opportunities worth a higher level of investment

- Sustain: Products we want to continue investing in, but not to differentiate

- Monitor: The capability is required to run a successful business, but the investment level may be reduced

There are some products that may have problems that need to be addressed immediately, or the investment levels are decreasing in certain areas of the product due to rationalization efforts. Those products are flagged with Fix or Exit so the MetaScrum can have prioritization conversations more easily.

The heightened levels of business intelligence and customer feedback the AOM has fostered allow leadership to make better decisions about investments faster. It also reduces the cost of pivoting when market conditions change.

Strong products, as well as prioritization and alignment at every level of the organization are what will make the portfolio process most effective at John Deere.

7. Agile Culture Unleashed

In-depth: .

John Deere has a long history of finding innovative solutions to common problems. Today, they’re still focused on driving customer efficiency, productivity, and value in sustainable ways.

As the company states , “We run so life can leap forward.”

That alone is enough to make the company iconic. For John Deere, that’s just the start.

People matter at John Deere. So too do concepts like purpose, autonomy, and mastery made famous by author Daniel Pink in his book Drive . “It’s no secret that there is a war for talent right now,” acknowledges Global IT Transformation Lead Josh Edgin, “and the market is only getting more competitive.” John Deere’s Global IT group is not immune to that competition. However, it has an advantage over other organizations — a thriving Agile culture.

Psychological safety, empowerment, risk-taking, are the foundations of the AOM. At John Deere’s Global IT group,being Agile isn’t defined by holding Scrum events, it’s about implementing Scrum the way it was intended by Scrum co-creator Jeff Sutherland.

Work-life balance is important. The environment is one of collaboration and respect. The group also has a common sense based remote work policy and a number of hubs for when collocation is imperative.

All this doesn’t mean everything is perfect at John Deere’s Global IT group. Leadership is the first to tell you they can and will do even better. This itself is a powerful statement — this is a place where continuous improvement is everyone’s goal, not something management demands of delivery teams.

“We’re a company that is walking the talk,” says Global IT Vice President Ganesh Jayaram, “We’re making investments both in terms of our team members and technology.” Here are just three of the important ways John Deere’s Global IT group is indeed “walking the talk.”

7.1 Transformation Portal

Big and visible. That is the goal of the group’s transformation portal. Everything relating to the AOM implementation can be found here.

Resources, wave schedules, thought leadership, and shared learnings are all available in this in-depth dashboard. Far more than you often see in other organizations. So too are metrics for individual teams and the group as a whole.

“People want purpose,” says Edgin, “they want to solve hard problems. They want to know the work they do matters.” This portal allows individuals to better understand their roles and they work together.

7.2 Agile Career Paths

Log into John Deere’s AOM transformation portal and you’ll find a section with dedicated self-learning and career advancement paths. As Amy Willard explains, “We have a path for every persona and community led CoPs, supported by the Foundry.” This includes everything from User Experience Practitioner to Scrum Master and Product Owner.

Having clearly defined career paths and self-learning opportunities is an important step. It not only empowers continuous improvement, but it also shows professional agilists that they’re valued, their skills are important, and they have a bright future at the organization which does not dictate they must choose between agility and career advancement.

7.3 Prioritizing Team and Organizational eNPS Scores

Through the AOM John Deere was focused on creating a great place to work. Leadership believed that healthy teams would drive creativity, productivity, and sustainability.

John Deere’s Global IT group regularly measures this through both team and organizational Employee Net Promoter Scores, or eNPS. By asking employees if they would recommend their team to others, leaders can gain a better understanding of the health and engagement of the team.

Edgin explains the importance of these metrics this way, “When you create a culture where you have awesome employees with the right mindset and great technical skills you want them to stay here because this is where they want to be.”

The Global IT group began with a 42-point baseline. A score above 50 is considered excellent. The group now has a score of 65, greater than the 20-point improvement targeted by leadership.

Individual teams show similar results across the board.

8. Metrics and Results

Truly successful Agile transformations don’t have a finish line. That’s why they call it a journey of continuous improvement.

Still, just two years into this implementation, John Deere’s Global IT group is clearly well down that path. The results are as indisputable as they are impressive.

“When you look at a product area and you see a 1,000 percent improvement can’t help but think they got the baseline wrong,” says Global IT Vice President Ganesh Jayaram.

But, digging deeper, the improvement is real.

Take the productivity gains seen from the teams with Order Management. Jayaram says these teams were chosen for the AOM’s pilot project because it was “the most complicated, had the most dependencies, and had tentacles throughout the organization.” He believed that if Scrum, Scrum@Scale, and the AOM worked for Order Management, other teams couldn’t question if it would work for them.

Metrics show just how successful the pilot was.

Both results are exponentially greater than the 125 percent increase target set for the transformation. While the Order Management results are leading the way, results from other business capability areas inside the Global IT group are closely following.

Take the ERP-heavy environment of Manufacturing Operations. Here, Edgin notes, thanks to the Agile transformation and the modernization of the technology stack, “this year we’ve delivered an order of magnitude more value and bottom-line impact to John Deere in the ERP space than in any previous year.”

He adds that “Every quality measure has improved. We’re delivering things at speeds previously not thought possible. And we’re doing it with fewer people.” Other Manufacturing Operations results include:

- Deploys: increased by 400 percent

- Features/Functions Delivered per Sprint: Has nearly tripled

8.1 Global IT Group Overall Results

Across the board, Deere’s Global IT Agile transformation has met or exceeded every initial goal set by senior leadership. Even when you combine results from both more mature teams and those that have just left the Foundry.

The targets that leadership set were to be reached within six months after completing immersion, but John Deere is seeing continued progress led by the business capability areas to achieve even higher results with the ongoing guidance of embedded change leaders such as Scrum Masters and business capability Agile coaches.

- Time to Market: Has been reduced by 63 percent — leadership initially sought a 40 percent reduction.

- Cost Efficiency: Leadership wanted to reduce the labor costs of the group by 20 percent . They have achieved this goal through insourcing and strategic hiring–even with the addition of Scrum and Agile roles.

8.2 Return on Investment and Impact on the Bottom Line

Agile transformations are an investment, in people, culture, productivity, innovation, and value delivery. Like any investment, transformations must deliver a positive return to be judged a success.

Deere’s ROI on the Global IT group’s transformation is estimated to be greater than 100 percent.

Successful Agile transformations also make a material impact on their company’s bottom line. Financially, 2021 was a banner year for John Deere. The company generated nearly $6 billion in annual net income — far more than its previous record. So, it takes a lot to materially impact the company’s bottom line.

Both Global IT Transformation Lead Josh Edgin and Global IT Vice President Ganesh Jayaram believe the AOM has indeed helped move the financial needle at Deere.

“The metrics we track show very clearly the answer is yes,” says Jayaram.

Edgin states, “We’re helping the company achieve our smart industrial aspirations by improving how we serve our customers and boosting productivity.” He adds that the AOM allows the group to “innovate and deliver high quality, secure solutions at a much faster pace to meet and exceed our customer needs.”

9. Agile in Action: Supply Chain Solutions Amid Disruptions

A global leader with more than 25 brands, John Deere relies on a complex supply chain and efficient logistics to ensure production and delivery go as planned.

More than 10,000 parts are needed to assemble just one of John Deere’s award-winning X9 combines — twice the number of components needed to build a new car.

Modern combines, just like modern farming, also require far more technology than you likely think.

Sensors, antennas, and motherboards are now just as critical as tires, treads, and tines. Of course, John Deere makes far more than combines. Its iconic logo appears on everything from tillers and tractors to marine engines, motor graders, and the John Deere Gator utility vehicle. In all, the company manufactures more than 100 distinct lines of equipment.

Each product relies on efficient and effective supply chain management — from procurement and sourcing to cost control, shipping, customs, and final delivery.