Little Hans – Freudian Case Study

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Case Study Summary

- Little Hans was a 5-year-old boy with a phobia of horses. Like all clinical case studies, the primary aim was to treat the phobia.

- However, Freud’s therapeutic input in this case was minimal, and a secondary aim was to explore what factors might have led to the phobia in the first place, and what factors led to its remission.

- From around three years of age, little Hans showed an interest in ‘widdlers’, both his own penis and those of other males, including animals. His mother threatens to cut off his widdler unless he stops playing with it.

- Hans’s fear of horses worsened, and he was reluctant to go out in case he met a horse. Freud linked this fear to the horse’s large penis. The phobia improved, relating only to horses with black harnesses over their noses. Hans’s father suggested this symbolized his moustache.

- Freud’s interpretation linked Hans’s fear to the Oedipus complex , the horses (with black harnesses and big penises) unconsciously representing his fear of his father.

- Freud suggested Hans resolved this conflict as he fantasized about himself with a big penis and married his mother. This allowed Hans to overcome his castration anxiety and identify with his father.

Freud was interested in the role of infant sexuality in child development. He recognised that this approach may have appeared strange to people unfamiliar with his ideas but observed that it was inevitable for a psychoanalyst to see this as important. The case therefore focused on little Hans’s psychosexual development and it played a key role in the formulation of Freud’s ideas within the Oedipus Conflict , such as the castration complex.

‘Little Hans’ was nearly five when he was seen by Freud (on 30th March 1908) but letters from his father to Freud provide the bulk of the evidence for the case study. These refer retrospectively to when Hans was less than three years old and were supplied to Freud through the period January to May 1908 (by which time little Hans was five years old).

The first reports of Hans were when he was 3 years old when he developed an active interest in his ‘widdler’ (penis), and also those of other people. For example, on one occasion, he asked, ‘Mummy, have you got a widdler too?

Throughout this time, the main theme of his fantasies and dreams was widdlers and widdling. When he was about three and a half years old his mother told him not to touch his widdler or else she would call the doctor to come and cut it off.

When Hans was almost 5, Hans’ father wrote to Freud explaining his concerns about Hans. He described the main problem as follows:

He is afraid a horse will bite him in the street, and this fear seems somehow connected with his having been frightened by a large penis’.

The father went on to provide Freud with extensive details of conversations with Hans. Together, Freud and the father tried to understand what the boy was experiencing and undertook to resolve his phobia of horses.

Freud wrote a summary of his treatment of Little Hans, in 1909, in a paper entitled “ Analysis of a Phobia in a Five-year-old Boy. “

Case History: Little Hans’ Phobia

Since the family lived opposite a busy coaching inn, that meant that Hans was unhappy about leaving the house because he saw many horses as soon as he went out of the door.

When he was first asked about his fear Hans said that he was frightened that the horses would fall down and make a noise with their feet. He was most frightened of horses which were drawing heavily laden carts, and, in fact, had seen a horse collapse and die in the street one time when he was out with his nurse.

It was pulling a horse-drawn bus carrying many passengers and when the horse collapsed Hans had been frightened by the sound of its hooves clattering against the cobbles of the road. He also suffered attacks of more generalized anxiety . Hans’ anxieties and phobia continued and he was afraid to go out of the house because of his phobia of horses.

When Hans was taken to see Freud (on 30th March 1908), he was asked about the horses he had a phobia of. Hans noted that he didn’t like horses with black bits around the mouth.

Freud believed that the horse was a symbol of his father, and the black bits were a mustache. After the interview, the father recorded an exchange with Hans where the boy said ‘Daddy don’t trot away from me!

Over the next few weeks Hans” phobia gradually began to improve. Hans said that he was especially afraid of white horses with black around the mouth who were wearing blinkers. Hans” father interpreted this as a reference to his mustache and spectacles.

- In the first, Hans had several imaginary children. When asked who their mother was, Hans replied “Why, mummy, and you”re their Granddaddy”.

- In the second fantasy, which occurred the next day, Hans imagined that a plumber had come and first removed his bottom and widdler and then gave him another one of each, but larger.

Freud’s Interpretation of Hans’ Phobia

After many letters were exchanged, Freud concluded that the boy was afraid that his father would castrate him for desiring his mother. Freud interpreted that the horses in the phobia were symbolic of the father, and that Hans feared that the horse (father) would bite (castrate) him as punishment for the incestuous desires towards his mother.

Freud saw Hans” phobia as an expression of the Oedipus complex . Horses, particularly horses with black harnesses, symbolized his father. Horses were particularly suitable father symbols because of their large penises.

The fear began as an Oedipal conflict was developing regarding Hans being allowed in his parents” bed (his father objected to Hans getting into bed with them).

Hans told his father of a dream/fantasy which his father summarized as follows:

‘In the night there was a big giraffe in the room and a crumpled one: and the big one called out because I took the crumpled one away from it. Then it stopped calling out: and I sat down on top of the crumpled one’.

Freud and the father interpreted the dream/fantasy as being a reworking of the morning exchanges in the parental bed. Hans enjoyed getting into his parent’s bed in the morning but his father often objected (the big giraffe calling out because he had taken the crumpled giraffe – mother – away).

Both Freud and the father believed that the long neck of the giraffe was a symbol for the large adult penis. However Hans rejected this idea.

The Oedipus Complex

Freud was attempting to demonstrate that the boy’s (Little Hans) fear of horses was related to his Oedipus complex . Freud thought that, during the phallic stage (approximately between 3 and 6 years old), a boy develops an intense sexual love for his mothers.

Because of this, he sees his father as a rival, and wants to get rid of him. The father, however, is far bigger and more powerful than the young boy, and so the child develops a fear that, seeing him as a rival, his father will castrate him.

Because it is impossible to live with the continual castration-threat anxiety provided by this conflict, the young boy develops a mechanism for coping with it, using a defense mechanis m known as identification with the aggressor .

He stresses all the ways that he is similar to his father, adopting his father’s attitudes, mannerisms and actions, feeling that if his father sees him as similar, he will not feel hostile towards him.

Freud saw the Oedipus complex resolved as Hans fantasized himself with a big penis like his father’s and married to his mother with his father present in the role of grandfather.

Hans did recover from his phobia after his father (at Freud’s suggestion) assured him that he had no intention of cutting off his penis.

Critical Evaluation

Case studies have both strengths and weaknesses. They allow for detailed examinations of individuals and often are conducted in clinical settings so that the results are applied to helping that particular individual as is the case here.

However, Freud also tries to use this case to support his theories about child development generally and case studies should not be used to make generalizations about larger groups of people.

The problems with case studies are they lack population validity. Because they are often based on one person it is not possible to generalize the results to the wider population.

The case study of Little Hans does appear to provide support for Freud’s (1905) theory of the Oedipus complex. However, there are difficulties with this type of evidence.

There are several other weaknesses with the way that the data was collected in this study. Freud only met Hans once and all of his information came from Hans father. We have already seen that Hans’ father was an admirer of Freud’s theories and tried to put them into practice with his son.

This means that he would have been biased in the way he interpreted and reported Hans’ behavior to Freud. There are also examples of leading questions in the way that Hans’ father questioned Hans about his feelings. It is therefore possible that he supplied Hans with clues that led to his fantasies of marriage to his mother and his new large widdler.

Of course, even if Hans did have a fully-fledged Oedipus complex, this shows that the Oedipus complex exists but not how common it is. Remember that Freud believed it to be universal.

At age 19, the not-so Little Hans appeared at Freud’s consulting room having read his case history. Hans confirmed that he had suffered no troubles during adolescence and that he was fit and well.

He could not remember the discussions with his father, and described how when he read his case history it ‘came to him as something unknown’

Finally, there are problems with the conclusions that Freud reaches. He claims that Hans recovered fully from his phobia when his father sat him down and reassured him that he was not going to castrate him and one can only wonder about the effects of this conversation on a small child!

More importantly, is Freud right in his conclusions that Hans’ phobia was the result of the Oedipus complex or might there be a more straightforward explanation?

Hans had seen a horse fall down in the street and thought it was dead. This happened very soon after Hans had attended a funeral and was beginning to question his parents about death. A behaviorist explanation would be simply that Hans was frightened by the horse falling over and developed a phobia as a result of this experience.

Gross cites an article by Slap (an American psychoanalyst) who argues that Hans’ phobia may have another explanation. Shortly after the beginning of the phobia (after Hans had seen the horse fall down) Hans had to have his tonsils out.

After this, the phobia worsened and it was then that he specifically identified white horses as the ones he was afraid of. Slap suggests that the masked and gowned surgeon (all in white) may have significantly contributed to Hans’ fears.

The Freud Archives

In 2004, the Freud Archives released a number of key documents which helped to complete the context of the case of little Hans (whose real name was Herbert Graf).

The released works included the transcript of an interview conducted by Kurt Eissler in 1952 with Max Graf (little Hans’s father) as well as notes from brief interviews with Herbert Graf and his wife in 1959.

Such documents have provided some key details that may alter the way information from the original case is interpreted. For example, Hans’s mother had been a patient of Freud herself.

Another noteworthy detail was that Freud gave little Hans a rocking horse for his third birthday and was sufficiently well acquainted with the family to carry it up the stairs himself.

It is interesting to question why, in the light of Hans’s horse phobia, details of the presence of the gift were not mentioned in the case study (since it would have been possible to do so without breaking confidentiality for either the family or Freud himself).

Information from the archived documents reveal much conflict within the Graf family. Blum (2007, p. 749) concludes that:

“Trauma, child abuse [of Hans’s little sister], parental strife, and the preoedipal mother-child relationship emerge as important issues that intensified Hans’s pathogenic oedipal conflicts and trauma. With limited, yet remarkable help from his father and Freud, Little Hans nevertheless had the ego strength and resilience to resolve his phobia, resume progressive development, and forge a successful creative career.”

Support for Freud (Brown, 1965)

Brown (1965) examines the case in detail and provides the following support for Freud’s interpretation.

1 . In one instance, Hans said to his father –“ Daddy don”t trot away from me ” as he got up from the table. 2 . Hans particularly feared horses with black around the mouth. Han’s father had a moustache. 3. Hans feared horses with blinkers on. Freud noted that the father wore spectacles which he took to resemble blinkers to the child. 4 . The father’s skin resembled white horses rather than dark ones. In fact, Hans said, “Daddy, you are so lovely. You are so white”. 5 . The father and child had often played at “horses” together. During the game the father would take the role of horse, the son that of the rider.

Ross (2007) reports that the interviews with Max and Herbert Graf provide evidence of the psychological problems experienced by Little Hans’s mother and her mistreatment of her husband and her daughter (who committed suicide as an adult).

Ross suggests that “Reread in this context, the text of “A Phobia in a Five-year-old Boy” provides ample evidence of Frau Graf’s sexual seduction and emotional manipulation of her son, which exacerbated his age-expectable castration and separation anxiety, and her beating of her infant daughter.

The boy’s phobic symptoms can therefore be deconstructed not only as the expression of oedipal fantasy, but as a communication of the traumatic abuse occurring in the home.

Blum, H. P. (2007). Little Hans: A centennial review and reconsideration . Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 55 (3), 749-765.

Brown, R. (1965). Social Psychology . Collier Macmillan.

Freud, S. (1905). Three essays on the theory of sexuality . Se, 7.

Freud, S. (1909). Analysis of a phobia of a five year old boy. In The Pelican Freud Library (1977), Vol 8, Case Histories 1, pages 169-306

Graf, H. (1959). Interview by Kurt Eissler. Box R1, Sigmund Freud Papers. Sigmund Freud Collection, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

Graf, M. (1952). Interview by Kurt Eissler. Box 112, Sigmund Freud Papers. Sigmund Freud Collection, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

Ross, J.M. (2007). Trauma and abuse in the case of Little Hans: A contemporary perspective . Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 55 (3), 779-797.

Further Information

- Sigmund Freud Papers: Interviews and Recollections, -1998; Set A, -1998; Interviews and; Graf, Max, 1952.

- Sigmund Freud Papers: Interviews and Recollections, -1998; Set A, -1998; Interviews and; Graf, Herbert, 1959.

- Wakefield, J. C. (2007). Attachment and sibling rivalry in Little Hans: The fantasy of the two giraffes revisited. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 55(3), 821-848.

- Bierman J.S. (2007) The psychoanalytic process in the treatment of Little Hans. Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 62: 92- 110

- Re-Reading “Little Hans”: Freud’s Case Study and the Question of Competing Paradigms in Psychoanalysis

- An” Invisible Man”?: Little Hans Updated

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

A Cognitive-Behavior Therapy Applied to a Social Anxiety Disorder and a Specific Phobia, Case Study

George d tsitsas, antonia a paschali.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Department of Mental Health and Behavioral Sciences, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, 123 Papadiamantopoulou street, 11527 Athens, Greece. [email protected]

Contributions: AP and GT designed the protocol, administer the CBT therapy sessions, analyzed and interpreted the data, and wrote the paper.

Conflict of interests: the authors declare no potential conflict of interests.

Received 2014 Apr 22; Revised 2014 Jul 1; Accepted 2014 Jul 4; Collection date 2014 Nov 6.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/ ) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

George, a 23-year-old Greek student, was referred by a psychiatrist for treatment to a University Counseling Centre in Athens. He was diagnosed with social anxiety disorder and specific phobia situational type. He was complaining of panic attacks and severe symptoms of anxiety. These symptoms were triggered when in certain social situations and also when travelling by plane, driving a car and visiting tall buildings or high places. His symptoms lead him to avoid finding himself in such situations, to the point that it had affected his daily life. George was diagnosed with social anxiety disorder and with specific phobia, situational type (in this case acrophobia) and was given 20 individual sessions of cognitivebehavior therapy. Following therapy, and follow-up occurring one month post treatment, George no longer met the criteria for social phobia and symptoms leading to acrophobia were reduced. He demonstrated improvements in many areas including driving a car in and out of Athens and visiting tall buildings.

Key words: social phobia, specific phobia situational type, high places, cognitive behavior therapy

Introduction

Social anxiety disorder (SAD), also known as social phobia, is one of the most common anxiety disorders. Social phobia can be described as an anxiety disorder characterized by strong, persisting fear and avoidance of social situations. 1 , 2 According to DSMIV, 3 the person experiences a significant fear of showing embarrassing reactions in a social situation, of being evaluated negatively by people they are not familiar with and a desire to avoid finding themselves in the situations they fear. 4 , 5 Furthermore people with generalized social phobia have great distress in a wide range of social situations. 6 The lack of clear definition of social phobia has been reported by clinicians and researchers because features of social phobia overlap with those of other anxiety disorders such as specific panic disorder, agoraphobia and shyness. 7

According to ICD-10, 8 phobic anxiety disorders is a group of disorders in which anxiety is evoked only, or predominantly, in certain well-defined situations that are not currently dangerous. As a result these situations are characteristically avoided or endured with dread. The patient’s concern may be focused on individual symptoms like palpitations or feeling faint and is often associated with secondary fears of dying, losing control, or going mad. Contemplating entry to the phobic situation usually generates anticipatory anxiety. Phobic anxiety and depression often coexist. Whether two diagnoses, phobic anxiety and depressive episode, are needed, or only one, is determined by the time course of the two conditions and by therapeutic considerations at the time of consultation.

Prevalence of social phobia varies from 0-20%, depending on differences in the classification criteria, culture 9 , 10 and gender. 11-13 The onset of the disorder is considered to take place between the middle and late teens. 14 The NICE guidelines for social anxiety disorder, describe it as one of the most common of the anxiety disorders. Estimates of lifetime prevalence vary but according to a US study, 12% of adults in the US will have social anxiety disorder at some point in their lives, compared with estimates of around 6% for generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), 5% for panic disorder, 7% for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and 2% for obsessive-compulsive disorder. There is a significant degree of comorbidity between social anxiety disorder and other mental health problems, most notably depression (19%), substance-use disorder (17%), GAD (5%), panic disorder (6%), and PTSD (3%). 15

Social phobia is also developed and maintained by complex physiological, cognitive, and behavioral mechanisms. Biological causes of social anxiety/phobia have been reported by some researchers while others look on behavioral inhibition 16 and the effects of personality traits such as neuroticism and introversion 17 as the mediators between genetic factors and social phobia.

Apart from the biological factor, the role of cognition in the acquisition and maintenance of social anxiety/phobia is very important. The main cognitive factor is the fear of negative evaluation. 18 Beck, Emery, and Greenberg 19 associated the possibility of negative evaluation by others with beliefs of general social inadequacy, concerns about the visibility of anxiety, and preoccupation with performance or arousal. 20

Specific phobia situational type, is described as a persistent fear that is excessive or unreasonable cued by the presence or anticipation of a specific object or situation such as public transportation, tunnels, bridges, elevators, flying, driving or enclosed places. This subtype has a bimodal age-at-onset distribution with one peak in childhood and another peak in mid-20s. 21

Exposure to the phobic stimulus almost invariably provokes an immediate anxiety response which may take the form of a situational bound or situational predisposed panic attack. The phobic situation usually is avoided or else is endured with intense anxiety or distress. The avoidance interferes often with the person’s normal routine occupational functioning, social activities or relationships. 21 Fear of heights, or acrophobia, is one of the most frequent subtypes of specific phobia frequently associated to depression and other anxiety disorders. 22 It is one of the most prevalent phobias, affecting perhaps 1 in 20 adults. Heights often evoke fear in the general population too, and this suggests that acrophobia might actually represent the hypersensitive manifestation of an everyday, rational fear. 23

From a behavioral perspective, feared situations negatively maintain phobias. Anxiety disorders have been shown to be effectively treated using cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) and therefore to better understand and effectively treat phobias. The CBT model used in the present case, was based on Clark and Wells 24 model that places emphasis on self-focused attention as social anxiety is associated with reduced processing of external social cues. The model pays particular attention to the factors that prevent people, who suffer from social phobias, from changing their negative beliefs about the danger inherent in certain social situations.

The following case it is a good representation of this model.

Case Report

George, was a 23-year-old single, Caucasian male student in his last academic year and was referred to a University Counseling Centre in Athens. The Centre provides free of charge, treatment sessions to all University students requiring psychological support.

George was diagnosed with Social Anxiety Disorder and with Specific phobia, Situational Type i.e . acrophobia. He was living alone in Athens, as his parents live in a different region of Greece. He was an only child. When asked about his childhood, he said that he had been happy and did not report any traumatic events. He described a close relationship with both his parents and when asked, he did not report any family history of psychiatric or psychological disorders or substance abuse problems.

He complained of severe symptoms of anxiety and phobias during the last six months. He began experiencing severe heart palpitations, flushing, fear of fainting and losing control, when travelling by plane, when crossing tall bridges while driving or when being in tall buildings or high places, however he did not experience symptoms of vertigo. Additionally, he reported significant chest pain and muscle tension in feared situations. His fear of experiencing these symptoms worsened and led him to avoid these situations which made his everyday life difficult. He also experienced similar symptoms when introduced to people or meeting people for the first time. He repeatedly went to see various doctors many times in order to exclude any medical conditions. George stated that he didn’t experience any symptoms of depression, had no prior psychological or psychiatric treatment and/or medication, and had first experienced this problem in the course of the previous year.

At the time of the intake, George was in his final exams which he wanted to finish successfully, and continue his studies abroad. Due to his condition, he decided not to apply for a postgraduate degree in the United Kingdom, which he always wanted, and started looking for alternative postgraduate courses in Greece.

Assessment and treatment

George was referred by a private psychiatrist. The psychiatrist used the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview, 25 which is a structured interview based on DSM-IV diagnostic criteria. George met the criteria for a Social anxiety disorder. He also met the criteria for specific phobia limited-symptom, which was secondary to his social phobia. The psychiatrist suggested to George, to better help him with his current symptoms to take selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). George however refused to take any medication and the psychiatrist referred him to the Counseling Centre. For the specific case we decided to give individual cognitive behavior therapy based on Clark and Wells model for Social Anxiety Disorder, 24 as referred into the NICE guidelines. 26 To better assist conceptualization and treatment and also monitor his progress, two therapists were assigned to George and two assessment measures (STAI and SPAI) were given, prior to the course of treatment, following therapy and at one month follow-up. He also had to complete a self-monitoring scale through-out the 20 weeks of treatment.

Monitoring progress measures

State-trait anxiety inventory.

The state-trait anxiety inventory (STAI), 27 the appropriate instrument for measuring anxiety in adults, differentiates between state anxiety , which represents the temporary condition and trait anxiety , which is the general condition. The STAI includes forty questions, with a range of four possible responses. In each of the two subscales scores range from 20 to 80, high scores indicating a high anxiety level. Higher scores correspond to greater anxiety.

Social Phobia and Anxiety Inventory

The Social Phobia and Anxiety Inventory (SPAI) 28 is a 45 item self-report measure that assesses cognition, physical symptoms, and avoidance/escape behavior in various situations. It includes two subscales: Social Phobia and Agoraphobia. A difference score above 60 indicates a potential phobia, and a cut off score of 80 maximizes this identification rate.

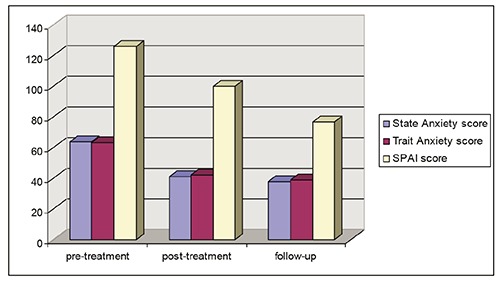

George’s pre-treatment scores were, SPAI:126, State Anxiety: 64 and Trait Anxiety: 63. The ultimate goal in each situation was to reduce the client’s level of anxiety.

Cognitive-behavior techniques such as self-monitoring, cognitive restructuring, relaxation, breathing retraining, and assertiveness training were employed to reduce anxiety and fear.

Cognitive behavior therapy techniques

Self-monitoring.

Self-monitoring refers to the systematic observation and recording of one’s own behaviors or experiences on several occasions over a period of time. 29 Self-monitoring can be used as a therapeutic intervention, because it helps the patient to evaluate his/her thoughts, emotions, and behaviors, recognize the feared situations and find appropriate solutions. Kazdin 30 states that self-monitoring can lead to dramatic changes, while Korotitsch and Nelson-Gray 29 add that although the therapeutic effects of self-monitoring may be small, they are rather immediate. George was asked to monitor his thoughts, feelings, and behaviors and record any changes.

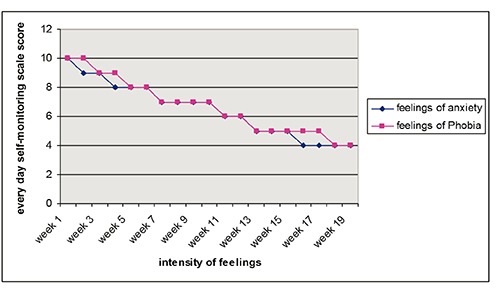

George had to complete an Every Day Self-Monitoring Scale for 20 weeks measuring feelings of anxiety (0=no anxiety to 10= most anxiety) and phobia (0=no feelings of phobia to 10=most feelings of phobia), ( Figure 1 ).

Every day self-monitoring scale score.

Cognitive restructuring

Beck and Emery, 19 have identified three phases in cognitive restructuring: i) identification of dysfunctional thoughts ii) modification of dysfunctional thoughts and iii) assimilation of functional thoughts. During cognitive restructuring, the client starts recognizing his/her automatic or dysfunctional thoughts and emotions that derive from this thoughts. For example, one of George’s thoughts was that: it is dangerous to drive at night , which made him feel very anxious and frightened. However, an adaptive thought could be that: that sometimes is dangerous but also a lot of times are not, due the fact that at night there is less traffic in the streets . Therefore, throughout the sessions he was taught how to substitute several automatic negative thoughts with adaptive ones. He also kept a dysfunctional thought record for 6 sessions, which he discussed with his therapist every week.

Muscle relaxation

Relaxation techniques were used for the treatment of George’s symptoms and more specifically for the physiological manifestations of anxiety and panic. 31

George was trained in breathing and muscle relaxation exercises, based on Jacobson’s technique and he was given 8 relaxation training sessions, in order to establish a sense of control over his physical symptoms. The client learned to apply brief muscle relaxation exercises in his daily life and especially every time he had to face an uncomfortable situation.

Assertiveness training

Assertiveness training can be an effective part of treatment for many conditions, such as depression, social anxiety, and problems resulting from unexpressed anger. Assertiveness training can also be useful for those who wish to improve their interpersonal skills and sense of self-respect and it is based on the idea that assertiveness is not inborn, but is a learned behavior. Although some people may seem to be more naturally assertive than others are, anyone can learn to be more assertive. In the specific case the therapists helped George figure out which interpersonal situations are problematic to him and which behaviors need the most attention. In addition, helped to identify beliefs and attitudes the client might had developed, that lead him to become too passive. The therapist used role-playing exercises as part of this assessment.

Clinical sessions

George completed 20 individual, 50 min therapy sessions that took place within a period of 5 months. During the first session the rationale of the cognitive-behavioral treatment was analyzed and special emphasis was given to educate the patient on Social Anxiety disorder and Specific phobias. An introduction was made to the role that automatic thoughts play in our cognitions and helped him to recognize automatic negative thoughts and feelings. A self-monitoring diary of anxiety was given to him as homework. Emphasis was also given to establishing good rapport and collaboration in the therapeutic relationship. During the second session, George narrated stressful life events and reported specific cases in which the anxiety symptoms increased. He was also taught how to identify the three phases of cognitive restructuring and was given the dysfunctional thought record as homework. The third session was based on teaching him breathing exercises and muscle relaxation. Relaxation techniques were taught by a different therapist, with expertise in stress management and relaxation techniques. George was given 8 such sessions, each lasting 20 minutes while he also practiced the sessions daily at home and completed a Daily-form for progress monitoring.

Sessions 4 to 9 were devoted to ways of challenging dysfunctional thoughts by resorting to adaptive responses. At first we tried to recognize negative automatic thoughts during specific situations and record George’s mood in that situation. After recognizing George’s negative thoughts, emotions and behaviors, we worked on the evidence that supported these thoughts.

The next three sessions (10-12) were devoted to teach him assertiveness skills to learn to socialize with people more effectively. We explored what assertiveness meant for George, what prevented him from being assertive and what were the differences between assertive, submissive and aggressive behavior, which he found really helpful and role-playing exercises were initiated to exercise these skills.

Sessions 13-20 were devoted identifying anxiety provoking situations which were hierarchically classified according to the degree of anxiety they produced. An example is shown in Table 1 . Exposure to feared situations was performed by facing in vivo each level of the hierarchy and gradually practice each step, until he was confident enough to go on to the next.

Fear hierarchy for visiting tall buildings.

Accordingly, situations such as driving, crossing bridges etc were also explored.

During the last session, George referred to overcoming challenging experiences, such as meeting new people, visiting friends living in tall apartment buildings and crossing two high bridges, while driving to visit his parents in a different part of Greece. He effectively challenged his cognitions in all relevant situations and utilized muscle relaxation and breathing exercises to control feelings of anxiety. Last session was also devoted to discuss relapse prevention, ways to avoid it and how to overcome past failures and difficulties. Finally, we discussed how he could modify and apply the skills and techniques that he had learned, in his daily routine.

The post-treatment scores of STAI and SPAI obtained by George at termination indicated an improvement. The Social Phobia score dropped to 100, the Anxiety State score was 41 and the Trait score was 42.

During the follow-up session one month later, George talked about his improvement, he mentioned that his progress continued and that he was not experiencing any of the averse symptoms of the past, while driving, visiting tall buildings/bridges and meeting new people. He continued the relaxation and the cognitive restructuring exercises. The STAI & SPAI scales were administered again. The assessment revealed maintenance of gains in terms of reduced anxiety and fear symptoms with State anxiety score: 38, Trait anxiety score: 39 and SPAI score: 77 ( Figure 2 ).

STAI and SPAI Scores.

Treatment implications

In the present clinical case, George attended 20 individual sessions of CBT, in order to reduce his anxiety levels and phobias and learn how to monitor his progress in his daily life. His anxiety levels were reduced in social situations and also he managed to overcome his fear of heights in specific provoking situations. His progress was inevitable which was confirmed by the anxiety scores of the STAI and SPAI. The follow-up session that took place a month later, showed that his progress was sustained. The Every Day Self-Monitoring Scale during the 20 weeks period, showed a gradual reduction in self monitoring feelings of anxiety and phobias ( Figure 1 ).

However although we based our CBT model on Clark and Wells model for Social Anxiety, we had certain variations from the original model. For example, the Clark and Wells model suggests, that individual therapy for social anxiety disorder should consist of up to 14 sessions of 90 minutes’ duration over approximately 4 months. In our case study, the duration of each session lasted 50 minutes and we gave 20 sessions of individual therapy to our client over a period of 5 months, thus trying to tailor our client’s needs and requirements for treatment.

A good rapport was developed with George and that helped the entire treatment process. Working on a list of feared hierarchies in combination with relaxation training skills, George was able to manifest his high level anxiety visiting tall buildings, crossing tall bridges etc. Furthermore, the fact that George learned to identify his automatic thoughts, helped him to reduce his unpleasant feelings by alternating his thoughts. Role-playing exercises in order to acquire assertiveness training skills helped him in relation to meeting new people. It is also worth mentioning that George was motivated and completed his CBT homework every week, something that helped the therapeutic outcome.

Conclusions: recommendations to clinicians and students

Cognitive behavioral therapy is very effective in treating anxiety. It is a structured intervention that follows a general framework that is modified for each individual. For the successful treatment of social phobia, the cognitive behavior therapy must be thorough and comprehensive. Sometimes is needed to use combinations of techniques, like in this case we used traditional CBT techniques in combination with assertiveness skills training. Collaboration with other specialists is also advised for ultimate results, as in this case two therapists were involved, one main therapist and one specialist on stress management techniques. The cognitive-behavior therapist is important to adapt the session, on the basis of his/her client’s needs, for example in the case of George we used exposure based techniques and although the Counseling center offers a maximum of 6 therapeutic sessions, in the case of George we decided on 20 sessions, in order to fully accommodate his problem. It is also very important for the therapist to explain the rationale behind each CBT session and help the patient understand each session’s agenda up to the point he/she feels comfortable to set their own agenda during the session. However, despite the therapist’s best efforts, the patient often hesitates to carry out the everyday homework, thus sometimes delaying the therapeutic progress. Therefore, the good rapport established with the patient will almost certainly add greatly to his/her adherence during the treatment.

Therapist-client relationship, play a fundamental role in the therapy process. It is important for the client to trust the therapist and feel comfortable within the therapy context. Creating a safe and empathetic environment is important from the first therapy session. Furthermore as CBT is directive, a strong therapeutic alliance is necessary to allow the client to feel safe engaging in this type of therapy. It is also important to mention that therapists need to refer to the widely accepted guidelines and recommendations for treating Social anxiety disorders and specific phobias, from widely accepted national institutes, such as the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence that covers both pharmaceutical and psychotherapeutic approaches. However, it is necessary sometimes to tailor-made therapy around client’s needs, as each case must be seen individually . There are too many manuals on CBT and there is the danger for the therapist to work in such a program that can lose creativity, individual thought, imagination and contact with the client. The crucial role of any therapeutic intervention, is not only to help people to acquire the techniques, but to feel comfortable to apply them daily in situations they feel discomfort.

- 1. Kaplan H, Sadock B. Synopsis of psychiatry. 8th ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1998. [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Hazen AL, Walker JR, Stein MB. Comparison of anxiety sensitivity in panic disorder and social phobia. Anxiety 1995;1:298-301. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2000. [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Bruch MA, Cheek JM. Developmental factors in childhood and adolescent shyness. Heimberg RG, Liebowitz MR, Hope DA, Schneier FR, eds. Social phobia: diagnosis, assessment and treatment New York: Guilford Press; 1995. pp 163-184. [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Rapee RM. Descriptive psychopathology of social phobia. Heimberg RG, Liebowitz MR, Hope DA, Schneier FR, eds. Social phobia: diagnosis, assessment and treatment New York: Guilford Press; 1995. pp 41-68. [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Adelman L. Don't call me shy. Austin, TX: Langmarc Publishing; 2007. [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Beidel DC, Morris TL, Turner MW. Social phobia. Morris TL, March JS, eds. Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford; 2004. pp 141-163. [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. World Health Organization. ICD-10 Version:2010. Phobic anxiety disorders. Available from: http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2010/en#/F40.

- 9. Browne MAO, Wells JE, Scott KM, McGee MA. Lifetime prevalence and projected lifetime risk of DSM-IV disorders in Te Rau Hinengaro: the New Zealand mental health survey. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2006;40:865-74. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. Wittchen HU, Fehm L. Epidemiology and natural course of social fears and social phobia. Acta Psychiatr Scand Supp 2003;417:4-18. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Kessler RC, McGonagle K, Zhao S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National comorbidity survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994;51:8-19. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Antony MM, Barlow DH. Social and specific phobias. Tasman A, Kay J, Lieberman JA, eds. Psychiatry. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1997. [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Schneier FR, Johnson J, Hornig CD, et al. Social phobia: comorbidity and morbidity in an epidemiological sample. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992;49:282-8. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Wells JE, Browne MAO, Scott KM, et al. Prevalence, interference with life and severity of 12 month DSM-IV disorders in Te Rau Hinengaro: the New Zealand mental health survey. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2006;40:845-54. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Social anxiety disorder: recognition, assessment and treatment. [NICE Clinical Guideline 159]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg159 [ PubMed ]

- 16. Schmidt LA, Polak CP, Spooner AL. Biological and environmental contributions to childhood shyness: a diathesis-stress model. In: Crozier WR, Alden LE, eds. The essential handbook of social anxiety for clinicians. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons; 2001. pp 33-55. [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Stemberger RT, Turner SM, Beidel DC, Calhoun KS. Social phobia: an analysis of possible development factors. J Abnormal Psychol 1995;104:525-31. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Mattick RP, Page A, Lampe L. Cognitive and behavioural aspects. Stein M, ed. Social phobia: cinical and research perspectives. Washington: American Psychiatric Press; 1995. [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Beck AT, Emery G, Greenberg R. Anxiety disorders and phobias: a cognitive perspective. New York: Basic Books; 1985. [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Hartman LM. A metacognitive model of social anxiety: implications for treatment. Clin Psychol Rev 1983;3:435-56. [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. American Psychiatric Association, DSM-IV, 4th ed. Text revision. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Coelho CM, Wallis G. Deconstructing acrophobia: physiological and psychological precursors to developing a fear of heights. Depress Anxiety 2010;27:864-70. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Boffino CC, de Sá CS, Gorenstein C, et al. Fear of heights: cognitive performance and postural control. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2009;259:114-9. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Clark DM, Wells A. A cognitive model of social phobia. Heimberg R, Liebowitz M, Hope DA, Schneier FR, eds. Social phobia: Diagnosis, assessment and treatment. New York: Guilford Press; 1995. pp 69-93. [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Janavs J, et al. Mini international neuropsychiatric interview (M.I.N.I.). Tampa: University of South Florida Institute for Research in Psychiatry; 1994. [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Generalised anxiety disorder and panic disorder (with or without agoraphobia) in adults: management in primary, secondary and community care. [NICE Clinical Guideline 113]. Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg113/chapter/guidance

- 27. Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene RE. Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1970. [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Turner SM, Beidel DC, Dancu CV, Stanley MA. An empirically derived inventory to measure social fears and anxiety. Psychologic Assess 1989;1:35-40. [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Korotitsch WJ, Nelson-Gray RO. Self-monitoring in behavioral assessment. Fernandez-Ballesteros R, ed. Encyclopedia of behavioral assessment. London: Sage; 2003. pp 853-858. [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. Kazdin AE. Behavior modification in applied settings. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth; 2001. [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Barlow DH, Craske MG. Mastery of your anxiety and workbook. 2nd ed. San Antonio, TX: The Psychology Corporation: 1994. [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (260.8 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

- Test for Panic Disorder

- Online Therapy for Panic and Anxiety

- Test for Social Anxiety Disorder

- Online Therapy for Social Anxiety

- Generalized Anxiety

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

- Selective Mutism

- Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

- Help & Support

- Test for Social Anxiety

You are here

- Social Phobia/Anxiety Case Study: Jim

Jim was a nice looking man in his mid-30’s. He could trace his shyness to boyhood and his social anxiety to his teenage years. He had married a girl he knew well from high school and had almost no other dating history. He and his wife, Lesley, had three children, two girls and a boy.

At our first meeting, Jim was very shy and averted his eyes from me, but he did shake hands, respond, and smile a genuine smile. A few minutes into our session and Jim was noticeably more relaxed. "I’ve suffered with this anxiety for as long as I can remember", he said. "Even in school, I was backward and didn’t know what to say. After I got married, my wife started taking over all of the daily, family responsibilities and I was more than glad to let her."

If there was an appointment to be made, Lesley made it. If there was a parent-teacher conference to go to, Lesley went to it. If Jim had something coming up, Lesley would make all the social arrangements. Even when the family ordered takeout food, it was Lesley who made the call. Jim was simply too afraid and shy.

Indeed, because of his wife, Jim was able to avoid almost all social responsibility -- except at his job. It was his job and its responsibilities that brought Jim into treatment.

Years earlier, Jim had worked at a small, locally-owned record and tape store, where he knew the owner and felt a part of the family. The business was slow and manageable and he never found himself on display in front of lines of people. Several years previously, however, the owner had sold his business to a national record chain, and Jim found himself a lower mid-range manager in a national corporation, a position he did not enjoy.

"When I have to call people up to tell them that their order is in," he said, "I know my voice is going to be weak and break, and I will be unable to get my words out. I’ll stumble around and choke up....then I’ll blurt out the rest of my message so fast I’m afraid they won’t understand me. Sometimes I have to repeat myself and that is excruciatingly embarrassing........"

Jim felt great humiliation and embarrassment about this afterwards: he couldn’t even make a telephone call to a stranger without getting extremely anxious and giving himself away. That was pretty bad! Then he would beat himself up. What was wrong with him? Why was he so timid and scared? No one else seemed to be like he was. He simply must be crazy! After a day full of this pressure, anxiety and negative thinking, Jim would leave work feeling fatigued, tired, and defeated.

Meanwhile, his wife, being naturally sociable and vocal, continually enabled Jim not to have to deal with any social situations. In restaurants, his wife always ordered. At home, she answered the telephone and made all the calls out. He would tell her things that needed to be done and she would do them.

He had no friends of his own, except for the couples his wife knew from her work. At times when he felt he simply had to go to these social events, Jim was very ill-at-ease, never knew what to say, and felt the silences that occurred in conversation were his fault for being so backward. He knew he made everyone else uncomfortable and ill-at-ease.

Of course, the worst part of all was the anticipatory anxiety Jim felt ahead of time – when he knew he had to perform, do something in public, or even make phone calls from work. The more time he had to worry and stew about these situations, the more anxious, fearful and uncomfortable he felt.

REMARKS: Jim presented a very typical case of generalized social phobia/social anxiety. His strong anticipation and belief that he wouldn’t do well at social interactions and in social events became a self-fulfilling prophecy, and his belief came true: he didn’t do well. The more nervous and anxious he got over a situation, and the more attention he paid to it, the more he could not perform well. This was a very negative paradox or "vicious cycle" that all people with social anxiety get stuck in. If your beliefs are strong that you will NOT do well, then it is likely you will not do well. Therefore, thoughts, beliefs, and emotions need to be changed.

The depression (technically "dysthymia") that comes about after the anxious event continued to fuel the fire. "I’ll never be able to deal with this," Jim would tell himself, thus constantly reinforcing the fact that he saw himself as a failure and a loser.

Unusual in this situation is that Jim’s wife remained loyal to him, understood his problem to some extent, and even seemed to enjoy her role as the family’s "social director". The more and more she did for Jim, the more and more he could avoid. It got so bad that Jim, who loved to listen to new albums and read new books -- could not even go to stores or to the library. He would tell his wife what to buy and she would buy it. She even kept track of when the library books were due and made sure she took them back on time.

This family situation is unusual because most people with social anxiety/social phobia have an extremely difficult time making and continuing personal relationships -- because of self-consciousness and the need for more privacy than most other people. In fact, social phobia ranks among one of the highest psychological disorders when it comes to failed relationships, divorce, and living alone.

TREATMENT for Jim consisted of the normal course of cognitive strategies so that he would relearn and rethink what he was doing to himself. He was cooperative from the beginning, and progressed nicely doing therapy. He took each of the practice handouts and spent time each day practicing. He made a "special time" for himself that his family respected and he used this place and time to practice the cognitive strategies his mind had to learn.

His biggest real-life fear, speaking to another person in public, was not really a speaking problem; it was an anxiety problem. There was nothing wrong with Jim’s voice, his reading ability, or his speaking ability. Jim was a bright man who had associated great anxiety around these social events in public situations.

The course of treatment here is NOT to practice! In fact, practicing would just draw attention to what Jim perceived was the problem: his voice, his awkwardness, his perceived inability to speak to others. Thus, it would reinforce the very behaviors we do not want to reinforce.

Instead, Jim worked on paradoxes. We deliberately goofed-up. We tried to make as many mistakes as possible. We injected humor into the situation and found that when he exaggerated his fears, he thought this was funny. Although more is involved than just this, the concept here is to de-stress the situation and enable the person to see it for what it is: NO BIG DEAL! If you make a mistake, SO WHAT? Everyone else does too!

Over the weeks, before group therapy began, Jim did a number of interesting things in public that began proving to him that he was NOT the center of attention, and it just didn’t matter if he made a mistake or two. After all, he was human just like everyone else. It’s this idea of perfectionism, of always having to "do your best" that must be broken down. Jim was human; humans make mistakes; so what? It was certainly nothing to get upset about. In fact, as time went by, it become even more funny and humorous, rather than humiliating or embarrassing.

After completion of the behavioral group therapy, Jim had an opportunity for advancement in his company, which he now felt comfortable to take. The promotion entailed holding weekly meetings in which he was in charge. He would have to do some public speaking and respond to his employees’ questions. By this time, Jim was feeling much more comfortable and much less anxious about the whole situation. "I think I’ll deliberately goof up," he joked to me before the start of his new job. "It would be interesting to see how everyone else responds."

To say that Jim did not have any anticipatory anxiety before taking this position or before making his weekly presentations would be inaccurate. The difference was now they were manageable. They were simply minor roadblocks that could be overcome. Jim’s thinking about social events and activities had changed a great deal since the first day I saw him in therapy.

I talked to Jim a few months ago and everything was going well. His responsibilities at work had increased slightly, but Jim now had the ability and beliefs to deal with them. He was much more confident and had a feeling of being in control. He was doing more around the house and his wife was a little surprised at his metamorphosis. Luckily, this did not change the marriage dynamics adversely, and the last time I talked with him, Jim had become a father again: another little boy.

"He’s the last," Jim said, laughing over the phone, "I can’t get too distracted. I’ve got too many speeches to give now."

- social anxiety

- anxiety disorder

Social Anxiety

- A New Test for Social Anxiety Disorder

- Why We Prefer "Social Anxiety" to "Social Phobia"

- Visiting The Social Anxiety Therapy Group

- Thinking Problems: Correcting Our Misperceptions

- What is Social Anxiety/Social Phobia?

- Personal Statements for Social Anxiety

- The Scorpion's Sting: An Anxiety Parable

- Social Anxiety Questions and Answers

- Social Anxiety and Misdiagnosis

- Social Anxiety Disorder and Medication

- The Least Understood Anxiety Disorder

- What are "The Phobias"?

- Social Anxiety: Past and Present

- What is the Difference Between Panic Disorder and Social Anxiety Disorder?

- Ask Dr. Richards About Anxiety Disorders

Latest articles

- Depression and Anxiety Survey

Our History and Our Mission

The Anxiety Network began in 1995 due to growing demand from people around the world wanting help in understanding and overcoming their anxiety disorder. The Anxiety Clinic of Arizona and its website, The Anxiety Network, received so much traffic and requests for help that we found ourselves spending much of our time in international communication and outreach. Our in-person anxiety clinic has grown tremendously, and our principal internet tool, The Anxiety Network, has been re-written and re-designed with focus on the three major anxiety disorders: panic, social anxiety, and generalized anxiety disorder.

The Anxiety Network focuses on three of the major anxiety disorders: panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and social anxiety disorder.

In 1997, The Social Anxiety Association , a non-profit organization, was formed and now has its own website.

The Social Anxiety Institute , the largest site on the internet for information and treatment of social anxiety, has maintained an active website since 1998. Continuous, ongoing therapy groups have helped hundreds of people overcome social anxiety since 1994.

Site Navigation

- Anxiety Help and Support

- Bookstore and Digital Downloads

- Panic Disorder, with and without Agoraphobia

- Generalized Anxiety Disorder Information

- Social Anxiety Disorder Information

- Post-Traumatic-Stress-Disorder

Follow Dr. Richards

© 1995, 2020, The Anxiety Network

Thomas A. Richards, Ph.D., Psychologist/Founder

Matthew S. Whitley, M.B.A., Program Coordinator/Therapist

COMMENTS

Case Study Details. Mike is a 20 year-old who reports to you that he feels depressed and is experiencing a significant amount of stress about school, noting that he’ll “probably flunk out.”.

This case study deals with Sara, a 37-year-old social phobic woman who suffered from a primary fear of blushing as well as comorbid disorders, including obsessive-compulsive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder and spider phobia.

This case study deals with Sara, a 37-year-old social phobic woman who suffered from a primary fear of blushing as well as comorbid disorders, including obsessive-compulsive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder and spider phobia.

This paper presents the case of a 50-year-old, married patient who presented to the psychologist with specific symptoms of depressive-anxiety disorder: lack of self-confidence, repeated worries,...

When Hans was taken to see Freud (on 30th March 1908), he was asked about the horses he had a phobia of. Hans noted that he didn’t like horses with black bits around the mouth. Freud believed that the horse was a symbol of his father, and the black bits were a mustache.

Abstract. George, a 23-year-old Greek student, was referred by a psychiatrist for treatment to a University Counseling Centre in Athens. He was diagnosed with social anxiety disorder and specific phobia situational type. He was complaining of panic attacks and severe symptoms of anxiety.

Jim is a man who suffers from social anxiety and avoids most social situations. He seeks therapy to overcome his fear of speaking to strangers on the phone and in public. Learn how he uses cognitive strategies to change his thoughts, beliefs, and emotions.

This article presents the clinical case of a 38-year-old man with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). “William” reports longstanding excessive and uncontrollable worry about a number of daily life events, including minor matters, his family, their health, and work.

We present the clinical case of a 14-year-old boy with gerascophobia or an excessive fear of aging, who felt his body development as a threat, to the point where he took extreme measures to stop or otherwise hide growth. He had a history of separation anxiety, sexual abuse, and suffering bullying.

Presents a case report of a 36-year-old Caucasian American who lives with her husband of 14 years. As a teenager she began experiencing occasional panic attacks, which became more severe and frequent in her senior year of college.