To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, risk management in tourism ventures.

The Emerald Handbook of Entrepreneurship in Tourism, Travel and Hospitality

ISBN : 978-1-78743-530-8 , eISBN : 978-1-78743-529-2

Publication date: 11 July 2018

This chapter aims to present the key issues and main aspects of risk management (RM), as they relate to tourism entrepreneurship, with a focus on the RM plan and the various strategies used in controlling risks.

Methodology/approach

Literature review was conducted and managerial issues and aspects regarding RM in tourism entrepreneurship were highlighted. These issues were illustrated by one example and two case studies from the business world.

This chapter suggests that every probable risk must have a pre-formulated plan to deal with its possible consequences. In the field of tourism entrepreneurship, the elimination of risk by putting safety measures in place is not simply achieved by taking precautions in a haphazard manner. Rather, these tasks require a proactive approach, an intricate and logical plan.

Research limitations

This chapter is explorative in nature, based on a literature review and case study analysis. It takes more entrepreneurial/practical than academic approach.

Managerial/practical implications

This chapter provides RM process as a generic framework for entrepreneurs/managers in the identification, analysis, assessment, treatment and monitoring of risk related to their business ventures. It also suggests the appropriate steps to follow to efficiently managing risks. Every tourism enterprise should have a strategy and an emergency/contingency plan to address risks.

Originality/value

This chapter outlines, in a comprehensive and practical way, a strategic approach to risk management for the tourism enterprises. It also highlights the importance and utility of planning and implementing of a suitable strategy to effectively address business-related risks.

- Risk management

- Tourism venture

Papaioannou, E. and Shen, S. (2018), "Risk Management in Tourism Ventures", Sotiriadis, M. (Ed.) The Emerald Handbook of Entrepreneurship in Tourism, Travel and Hospitality , Emerald Publishing Limited, Leeds, pp. 223-240. https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-78743-529-220181017

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2018 Emerald Publishing Limited

We’re listening — tell us what you think

Something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

- BBA Public Accounting

- BBA General Business

- BBA Finance

- BBA Management

- BBA Marketing

- BBA Risk Management & Insurance

- Master of Business Administration (MBA)

- Certificate in Accounting

- Certificate in Banking & Financial Services

- Certificate in Financial Literacy

- Certificate in Financial Technology & Cybercrime

- Certificate in Global Supply Chain Management

- Graduate Certificate in Functions of Business

- BS Child & Family Studies – Child Development

- Certificate in Early Childhood Director

- Certificate in Family Services

- Certificate in Infant/Toddler Care and Education

- BA Communication Studies

- Certificate in Communication Studies

- Certificate in Dispute Resolution

- Certificate in Communication in the Workplace

- MS Computer Science

- Certificate in Artificial Intelligence in Data Science

- Certificate in Cybersecurity and Digital Forensics

- Certificate in Game Design

- AA Police Studies

- BS Corrections & Juvenile Justice Studies

- BS Criminal Justice

- BS Police Studies

- MS Criminal Justice Policy & Leadership

- Certificate in Correctional Intervention Strategies

- Certificate in Juvenile Justice

- BS in Elementary Education

- MAEd Master of Arts in Education

- MAT Master of Arts in Teaching

- EdS Specialist in Education

- AS Paramedicine

- BS Emergency Medical Care — Emergency Services Administration

- BS Emergency Medical Care — Fire Service

- BS Fire, Arson & Explosion Investigation

- BS Fire Protection Administration

- BS Fire Protection & Safety Engineering Technology

- Certificate in Industrial Fire Protection

- AA General Studies

- BA General Studies

- BS Health Services Administration

- BS Homeland Security

- MS Safety, Security & Emergency Management

- Certificate in Homeland Security

- Certificate in Security Management

- BS Global Hospitality and Tourism

- Undergraduate Certificate in Gastronomic Tourism

- Undergraduate Certificate in Sustainable Hospitality

- MS Instructional Design & Learning Technology

- Graduate Certificate in Online Learning Design

- Graduate Certificate in User Experience Design

- MS Nursing – Rural Health Family Nurse Practitioner

- MS Nursing – Psychiatric Mental Health Nurse Practitioner

- DNP Post-MSN DNP

- Post-MSN Certificate – Family Nurse Practitioner

- Post-MSN Certificate – Psychiatric Mental Health Nurse Practitioner

- BS Occupational Safety

- MS in Safety, Security & Emergency Management

- Graduate Certificate Construction Safety

- Graduate Certificate in Cyber & Security Management

- Graduate Certificate in Emergency Management & Disaster Resilience

- Graduate Certificate Healthcare Safety

- Graduate Certificate in Occupational Safety

- Graduate Certificate in Safety Leadership & Management

- Graduate Certificate in Supply Chain Safety & Security

- Certificate in Social Intelligence & Leadership

- Bachelor’s to OTD

- Master’s to OTD

- AAS Paralegal Studies

- BA Paralegal Science

- Post-Baccalaureate Certificate in Paralegal Science

- BA Political Science

- BS Psychology

- Certificate in Veterans Studies

- MS Psychology-Applied Behavior Analysis

- MS Industrial Organizational Psychology

- Graduate Certificate in Psychology — Applied Behavior Analysis

- MPA Public Administration

- Certificate in Community Development

- Certificate in Emergency Management & Disaster Resilience

- Certificate in Applied Policy

- Certificate in Non-Profit Management

- Master of Public Health – Health Promotion

- BSW Social Work

- MSW Social Work

- Certificate in Addictions Intervention

- Certificate in Child & Family Services

- Certificate in Leadership & Management

- Certificate in Mental Health

- Certificate in Social Advocacy & Justice

- BS Sport Management

- See All Programs

- Types of Financial Aid

- Applying for Financial Aid

- Understanding Financial Aid

- Financial Aid Policies

- Scholarships

- How to Apply

- Application Deadlines

- Admission Requirements

- Transfer Students

- Transfer from KCTCS

- Visiting & Non-Degree Seeking Students

- Corporate Educational Partnerships

- State Authorization & Professional Licensing Information

- Student Resources

- Faculty Resources

- Online Military Students

- BBA Risk Management & Insurance

- BS Child & Family Studies – Child Development

- BS Corrections & Juvenile Justice Studies

- MS Criminal Justice Policy & Leadership

- BS Fire, Arson & Explosion Investigation

- BS Fire Protection & Safety Engineering Technology

- MS Safety, Security & Emergency Management

- MS Instructional Design & Learning Technology

- MS in Safety, Security & Emergency Management

- Graduate Certificate in Cyber & Security Management

- Graduate Certificate in Emergency Management & Disaster Resilience

- Graduate Certificate in Safety Leadership & Management

- Graduate Certificate in Supply Chain Safety & Security

- Certificate in Social Intelligence & Leadership

- Certificate in Emergency Management & Disaster Resilience

- Certificate in Child & Family Services

- Certificate in Leadership & Management

- Certificate in Social Advocacy & Justice

Risk and Crisis Management in the Hospitality and Tourism Industry

The hospitality and tourism industry like other industries, faces the challenge of managing risk and crisis. As an industry that involves human contact and provides services, its vulnerability to risk and crisis is even higher. Since crises occur when least expected, it is important to have a risk management plan establishing the steps to be taken in the case of a crisis. Planning for a crisis can help reduce the negative consequences, and better allows businesses or stakeholders to deal with unwanted and unplanned events. There are several risks related to the hospitality and tourism industry.

Data Privacy Risks

Data privacy issues can be major a major risk within the industry. Nowadays, most businesses in the industry collect customer data such as spending patterns and financial information to better provide customized services and increase customer satisfaction. Customers who provide personal information believe their data will be safe and carefully guarded. However, large data breach incidents exposing customers’ personal information have occurred. Businesses must do all they can to lower the risk of or manage such crises. To reduce risks associated with customer data, businesses can implement data encryption for payment and personal information. Additionally, they can provide continuous training to employees about cybersecurity issues.

Environmental Risks

Another risk in the hospitality and tourism industry are environment-related crises. Because industry provided products and services are located at a specific destination, natural disasters such as earthquakes, hurricanes, or other extreme weather disasters can occur. Also, as we have recently seen with COVID, health-related incidents such as pandemics also pose significant risk. COVID dramatically impacted the hospitality and tourism industry because of travel regulations and large numbers of people refusing to travel. To cope with the current situation, many businesses in the industry have found ways to provide a similar experience or product while adhering to COVID guidelines and restrictions. One good example of this shift is restaurants selling meal kits or focusing more on to-go orders. Hotels have also started to emphasize the cleanliness and safety of their properties to draw guests.

While risks and crises are unpredictable, we know a crisis will happen at some point. Therefore developing methods to manage such risks or crises when they occur is important in order to minimize the damage and recover as quickly as possible.

Interested in advancing your career in hospitality and tourism?

Earn your bachelor’s degree from a regionally accredited university that has been an online education leader for over 15 years. Complete the form to learn more about how you can earn your bachelor’s in global hospitality and tourism . You can also earn an in-demand certificate in gastronomic tourism or sustainable hospitality along the way.

By: Daegeun (Dan) Kim, M.S., CHIA, assistant professor, Global Hospitality and Tourism

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Crisis management research (1985–2020) in the hospitality and tourism industry: A review and research agenda

Associated data.

The global tourism industry has already suffered an enormous loss due to COVID-19 (Coronavirus Disease 2019) in 2020. Crisis management, including disaster management and risk management, has been becoming a hot topic for organisations in the hospitality and tourism industry. This study aims to investigate relevant research domains in the hospitality and tourism industry context. To understand how crisis management practices have been adopted in the industry, the authors reviewed 512 articles including 79 papers on COVID-19, spanning 36 years, between 1985 and 2020. The findings showed that the research focus of crisis management, crisis impact and recovery, as well as risk management, risk perception and disaster management dominated mainstream crisis management research. Look back the past decade (2010 to present), health-related crisis (including COVID-19), social media, political disturbances and terrorism themes are the biggest trends. This paper proposed a new conceptual framework for future research agenda of crisis management in the hospitality and tourism industry. Besides, ten possible further research areas were also suggested in a TCM (theory-context-method) model: the theories of crisis prevention and preparedness, risk communication, crisis management education and training, risk assessment, and crisis events in the contexts of COVID-19, data privacy in hospitality and tourism, political-related crisis events, digital media, and alternative analytical methods and approaches. In addition, specific research questions in these future research areas were also presented in this paper.

1. Introduction

A crisis is defined as ‘an unpredictable event that threatens important expectancies of stakeholders related to health, safety, environmental, and economic issues, which can seriously impact an organisation's performance and generate negative comments' ( Coombs, 2019 , p. 3). Today's hospitality and tourism industry is sensitive to various external and internal challenges and crises ( Fink, 1986 ; Henderson, 2003 ; Laws et al., 2005 ; McKercher & Hui, 2004 ). According to McKercher and Hui (2004 , p.101), crises ‘disrupt the tourism and hospitality industry on a regular basis’. The reduction of tourist arrivals and expenditures due to the crises hits the industry and its related stakeholders; and creates vulnerability. Different service providers (consisting of those pertaining to accommodation, transportation, inbound and outbound tourism, and others) may have to suffer for a short or longer period of time before full recovery. Moreover, pressures from competitors also worsened the situations for certain organisations due to the change in comparative and competitive advantages ( Wut, 2019 ). Only a few studies in crisis management were conducted in the early years, and most of them related to crisis impacts on tourism industry ( Blake & Sinclair, 2003 ). Fortunately, a growing body of crisis management studies in the hospitality and tourism industry has emerged over the past decade.

The scope of crisis management includes crisis prevention, crisis preparedness, crisis response and crisis revision ( Hoise & Smith, 2004 ). Detecting any warning signs is an important task in crisis prevention. Crisis preparedness usually involves forming crisis management teams, formulating crisis preparedness plans and training spokespersons. Organisation response is usually under the spotlight. The mechanism by which we learn from a crisis is a central topic under crisis revision ( Crandall et al., 2014 ). Unfortunately, crisis management received insufficient attention in the hospitality and tourism research for decades ( Pforr & Hosie, 2008 ). This research stream started with natural disaster management, terrorism and disease management ( Laws et al., 2005 ). Recently, information technology has been heavily used in the business and tourism sectors ( Buhalis & Law, 2008 ; Navio-Marco et al., 2018 ). Social media is becoming an emerging research focus that triggers new thoughts on crisis management in the contemporary world ( Zeng & Gerritsen, 2014 ). Data security and privacy over confidential company information and customer personal information are the main concerns. Nowadays, given the global outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic and the economic downturn faced by many countries, crisis management has again attracted organisational and research attention ( Qiu et al., 2020a , b ; Gössling et al., 2020 ).

Crisis management also involves risk management, as crisis happens when risk is not managed properly and effectively. For instance, if tourism providers do not pay attention to risk management may put the lives of the tourists at risk. According to Dorfman and Cather (2013) , risk is the possibility of harm or possible loss. Risk refers to the fluctuation in neutral or negative outcomes that result from an uncertain event on the basis of probability. Risk management is a process in which an organisation identifies and manages its exposures to risk to match its strategic goals. The scope includes goals setting, risk identification, risk measurement, handling of risk and implementation techniques, and effectiveness of monitoring ( Dorfman & Cather, 2013 ).

Crises in extreme scales with catastrophic consequences can be disasters. Disasters normally refer to events that an organisation cannot control, like natural disasters. Possible disaster events include terrorism, floods, hurricanes and earthquakes. The term ‘crisis’ has a broad meaning that includes events involving technical or human mistakes as well as disasters ( Coombs, 2019 ; Faulkner, 2001 ). Thus, crisis management in this study covers both risk management and disaster management.

Several review papers on crisis management and recovery are available. Mair et al. (2016) conducted a review on post-crisis recovery with 64 articles published between 2000 and 2012. A short summary on tourism crisis and disaster was also published ( Aliperti et al., 2019 ). Ritchie and Jiang (2019) reviewed 142 papers on tourism crisis and disaster management; and identified three areas including crisis preparedness and planning; crisis response and recovery; and crisis resolution and reflection. It was found that the papers, including the framework testing, lack conceptual and theoretical foundation, which exhibited unbalanced research themes ( Ritchie & Jiang, 2019 ). A bibliometric study of citation networks was conducted by other researchers but only on the crisis and disaster management topic ( Jiang, Ritchie, & Verreynne, 2019 ). The most recent one was focused on diseases ( Chen, Law, & Zhang, 2020 ). The afore-said review articles followed the traditional classification of the three-stage crisis management model (pre-crisis, crisis event and post-crisis) ( Richardson, 1994 ). A clear research gap exists in the review literature in terms of the kind of crisis management, risk management and disaster management research that has been conducted in the hospitality and tourism fields, especially in the digital era; and such research need becomes significant due to the spread of COVID-19. This current review paper considers risk management and disaster management as part of crisis management. This review scope is much wider than those of past review papers. Furthermore, past literature review emphasised only the research published in top academic journals. Zanfardini et al. (2016) concluded that analyses of literature should not be confined to the highest impact journals because crisis management is an interdisciplinary subject; and the related articles might not necessarily appear only in the top journals. Thus, surveying also the lower impact journals would be useful, and this study would also shed light on those works.

This study aims to systematically examine and evaluate the literature of crisis management in the hospitality and tourism industry. As the research areas emerge, more papers were recorded in the last decade. It is expected that many research papers on topics relating to the COVID-19 crises will be produced shortly in the near future. The major themes and future research opportunities and agenda will be identified after a thematic content analysis of related peer-reviewed journal articles.

This study seeks to address the following questions:

- 1) What are the main themes of the crisis management literature in the hospitality and tourism industry?

- 2) What is the future research agenda regarding the hospitality and tourism industry and crisis management?

2. Methodology

This systematic literature review adopted steps suggested by Liberati et al. (2009) for the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA): 1) related articles were identified through databases and other sources, 2) records were obtained after the duplicates were removed, 3) the records were screened, 4) full-text papers were assessed for eligibility and 5) the studies were included in the qualitative synthesis ( Liberati et al., 2009 ).

We targeted our literature search on electronic databases for peer-reviewed journal articles that focused on crisis management in the hospitality and tourism industry and from journals published since 1980. The search included numerous academic platforms consisting of the ABI/Inform, Academic Research Premier (via EBSCO host), Business Source Complete (via EBSCO host), Web of Science and Scopus databases to capture academic journal papers with the captioned topic. This approach was considered suitable for a literature review analysis centred on a subject that has undoubtedly been researched from a multi-disciplinary perspective ( Wut et al., 2021 ). Literature search was organised around eight keywords consisting of ‘tourism’, ‘hospitality’, ‘crisis’, ‘crisis management’, ‘risk’, ‘risk management’, ‘disaster’ and ‘disaster management’. Papers retained for subsequent analyses met the following criteria:

- (i) Published in peer-reviewed journals since 1980;

- (ii) Published in the English language;

- (iii) Involves the field of business, management and accounting;

- (iv) Seeks to study crisis management, including risk management and disaster management, in the tourism and hospitality industry;

- (v) Comprise studies presenting primary or secondary research data published as full length papers or short reports;

- (vi) Removal of duplicate papers from database findings (Same paper generated from different platforms).

In total, 1168 papers were generated from the literature search which involves different combinations of the aforementioned keywords. The earliest article was published in 1985. Overall, the selected articles were published between 1985 and 2020. Figures for 2020 are incomplete and given here for reference only. Authors assessed the full-text papers retrieved for inclusion in this review.

The titles, abstracts and full texts of the papers were reviewed and examined ( Wut et al., 2021 ). Two coders were involved in the process to avoid subjective bias judgement from a single coder ( Neuendorf, 2002 ). Discussions between coders were arranged to resolve the discrepancy ( Krippendorff, 2013 ). After initial screening, 534 papers meeting the above criteria were selected. A subsequent step involved checking if the research questions of this study can be answered through analysing the papers in the database. A total of 22 papers were dropped as they could not answer one of the research questions. The final analysis involved 512 papers for subsequent descriptive analyses in various aspects like the number of authors, the first author's nationality and study locations. Papers involving more than one study location were classified under Global. Attention was paid to the themes of journals under the category of tourism, hospitality and others as business-related journals. Publications that covered both tourism and hospitality were classified under hospitality. We also identified the key topics of each article. These items were used for statistical analysis to identify longitudinal trends of research themes. The papers were categorised under various hospitality and tourism industry sectors, including tour operators/travel agencies, hotels, airlines, restaurants and ocean cruising industry. They were then assigned to one of the six crisis types: political events, terrorism, health issues, financial crisis, natural disasters and human errors. The research foci of the articles were subsequently ascertained and summarised. The identification process was completed by content analysis for which an inductive approach was adopted. If any doubt regarding classification emerged for a particular paper, a new category was devised for that paper to minimise ambiguity ( Eisenhardt, 1989 ). When more than one topic was discussed in a paper (for example, crisis prevention and crisis preparedness), the paper was classified under the category of crisis management (multiple topics). Thus, 10 specific research topics were obtained for a general crisis management area: crisis management (multiple topics), crisis impact, crisis recovery, crisis resilience, crisis communication, crisis response, crisis event (description), crisis preparedness, crisis prevention and crisis management (organisational) learning. Four research topics were identified for a general risk management area: risk management (multiple topics), risk perception, risk assessment and risk communication. Finally, three research topics were found for a general disaster management area: disaster management (multiple topics), disaster event (description) and disaster recovery. COVID-19 was categorised as a separate topic, as the related articles covered the areas in both crisis and risk management.

3. Findings

3.1. journals, authors and study locations.

The results indicated that 308 (60.2%) of the papers came from 10 journals; and 204 papers were come from other journals. Among these 10 journals, Tourism Management published 85 papers; Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing published 44 papers, International Journal of Hospitality Management had 34 papers and Current Issues in Tourism had 33 papers. Annuals of Tourism Research published 26 papers, and Journal of Travel Research secured 25 papers. The publications were highly ranked according to the Scimago Journal and Country Ranking (SRJ). In the last decade, all these journals except for the Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing published more papers than before ( Table 1 ). Furthermore, other high ranking journals were included in the ‘Others’ category, including the Journal of Vacation Marketing with two papers. One paper appeared in the Public Relation Review, a top Journal in the field of public relations. Another paper was from the Journal of World Business, a first quarter journal according to the SRJ. Three other papers appeared in Asia Pacific Business Review, a second quarter journal according to the SRJ. Thus, crisis management has been considered a hot research topic by the scholars and high ranking academic journals in the hospitality and tourism field.

List of tourism and hospitality journals (N = 512).

As a whole, tourism-focused journals were comparatively favoured (286 papers) to hospitality (74 papers) or other (152 papers) journals on the crisis management topic and related research objectives. Among the tourism-focused journals, Tourism Management has been the dominant outlet. The number of papers increased by three times over the last decade. Among the hospitality journals, International Journal of Hospitality Management (34 papers) has been the most popular.

Regarding authorship, two authors collaboration (157 papers, 30.7%) has been found to be the most common occurrence in these papers. Three-person authorship was also highly adopted (143 papers, 27.9%), followed by single authorship for 129 papers (25.2%). Note that a total of 60 papers had four authors (11.7%), five authors (14 papers, 2.7%), six authors (7 papers, 1.4%), seven authors (1 paper, 0.2%), and eight authors (2 papers, 0.4%). Collaborations among authors are common. The most productive first authors in this field were Joan C. Henderson (9 papers), Bingjie Liu (9 papers), Bruce Prideaux (7 papers) and Brent W. Ritchie (6 papers). The most productive second authors were Lori Pennington-Gray (13 papers), Brent W. Ritchie (9 papers), Mehmet Altinay, Susanne Becken and Hany Kim (4 papers). Henderson comes from Nanyang Technological University and had publications in the early years (from 1999 to 2004). Liu is from the University of Florida. Most of her publications were related to bed bugs and were rather recent (from 2015 to 2016).

Location was studied for the first authors of the papers. The first authors tend to be most interested in the study topics relating to crisis management and may have secured fair level of research experience in this area. Europe (157 papers, 30.7%) had the greatest number of interested scholars who appeared as the first authors. This figure was followed by Asia (132 papers, 25.8%) and Oceania (110 papers, 21.5%). In Europe, the United Kingdom (59 papers) had the most interested scholars in this area. The first authors from Asia were mainly from Mainland China (29 papers), Israel, Singapore, Japan and Taiwan. The other first authors were from Australia (101 papers) and United States (88 papers) ( Table 2 is a short version of this list. An extended version is in the Appendix).

Location of first author (N = 512).

In terms of the research context, Asia was the most studied region (152 papers, 29.7%), followed by Global (109 papers, 21.3%), and then Europe (101 papers, 19.7%). Several disasters occurred in Asia, including the Japan earthquakes in 2011, the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) outbreak in 2003 and the Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami in 2004. Many papers took a global or multiple countries approach (109 papers, 21.3%). First authors also tend to conduct research in his or her place-of-residence or nearby locations ( Table 3 ).

Study location (N = 512).

An increasing trend emerged throughout the 36 years study period, as shown in Fig. 1 . The number of articles in 2020 is listed for reference and some articles could not be presented due to availability issues. All papers, whether from tourism-focused journals, hospitality journals or journals in the other fields, generally displayed an upward trend ( Fig. 2 ). Almost all top ten English-language academic journals in the tourism and hospitality field witnessed an increasing trend, except for the Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing which experienced a downward trend ( Fig. 3 ). The three periods were identified in the X-axis and spans 36 years. The first period from 1985 to 1996 reflects the start of the discussion about crisis management. Only six papers were published for 12 years. The second period of 1997–2008 involved 115 papers. During this period, most of the papers were published in the Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing and in Tourism Management. The last period of 2009 to present involved 389 papers. Most of the papers were published in Tourism Management. At this period, as many as 63 papers were published in Tourism Management. The number of papers published in Tourism Management is almost the sum of the numbers of the first runner up, and second runner up. ( Table 1 ).

Studies related to crisis management in the tourism and hospitality literature (1985–2020).

Numbers of tourism and hospitality publications in English on crisis management.

Top Ten Journals on crisis management.

3.2. Types of crises in the hospitality and tourism industry

The 512 papers revealed that five business sectors within the hospitality and tourism industry, an outcome which mirrored the findings of Wut et al. (2021) who performed a systematic review on corporate social responsibility research in the hospitality and tourism industry. The most commonly investigated industry sectors comprised tour operators/travel agencies, hotel operators, airlines, restaurants and ocean cruising sectors. Their crises types are summarised below for illustration purposes ( Table 4 ):

Typology of crisis types in hospitality and tourism industry (Source: authors).

Crisis types were previously organised under the three categories of natural disasters, technical error accidents and human error accidents, depending on the level of organisational responsibility. Limited organisational responsibility is clearly involved for natural disasters because those events are usually beyond operational control ( Coombs, 2019 ). Only reactive strategies can be developed to minimise loss. A low level of organisational responsibility occurs on technical error accidents as the organisation can hardly do much about technical errors. However, organisations should bear the main responsibility for preventable crises as they involve human errors ( Coombs, 2019 ). Natural disasters are the most common type, and the other two are mainly related to complaints on social media.

3.3. Methodological design of previous research

Almost half of the studies adopted quantitative research methods (215 studies, 42%). Approximately 34% of the papers relied on qualitative research methods (174 studies). Only 24 studies (4.7%) integrated both qualitative and quantitative research methods. And there also appeared 99 conceptual papers. In terms of research design, exploratory design (qualitative) dominated (159 studies, 31.1%). Most researchers used in-depth interview and focus group in exploratory design. This research design is followed by adopting primary data from surveys (139 studies, 27.1%) and using secondary data and databases (74 studies, 14.5%). For the statistical and analytical methods of research, the main method was identified for each paper. Most qualitative studies relied on case studies (85 studies, 16.6%) and content analysis (81 studies, 15.8%). Descriptive analysis (54 studies, 10.5%) and regression analysis (40 studies, 7.8%) were primarily used in the quantitative studies. When appeared more than one method of analysis was utilised (for example, both descriptive and regression analysis), only the most complex method was counted (in this case, regression analysis) ( Table 5 ).

Analysis by research methodology (N = 512).

3.4. Traditional Research focus

The research themes in the literature were organised in such manner: Papers with a specific topic of crisis management, risk management or disaster management were grouped under the category carrying the name of the focal topic, such as crisis impact, crisis recovery and risk perception. Papers on crisis management in general ( Beirman, 2001 ) or focusing on crisis management in relation to other topics, for example, brand management ( Balakrishnan, 2011 ), or those on more than one topic of crisis management such as crisis preparedness and organisational learning ( Anderson, 2006 ) were all included under a category named “Crisis management/with multiple topics”. Similar logic was applied to the “Risk management/with multiple topics” category, which included papers embracing risk management in general ( Angel et al., 2018 ) or multiple topics regarding risk identification, the influential factors and related risk management practices ( Chen, 2013 ). This logic was further applied to the “Disaster management/with multiple topics” category. Another category refers to COVID-19, which has been a hot topic since last year. All the COVID-19 papers that concerned about crisis and/or crisis management were put under this separate category. Such arrangement could help summarise the focuses and trends of COVID-19 research and facilitate the researchers who may have continuing interests to explore further in future years. Lastly, the remaining papers hardly put into previous categories were put under the category of others. As a result of adopting the above rationale in papers classification, among the reviewed studies, 16% (82 papers) were related to crisis management/with multiple topics and 15.4% (79 papers) related to COVID-19. These two primary categories were found in terms of the number of papers collected ( Table 6 ). Risk management/with multiple topics is the second runner-up with 13.7% (70 papers). Risk perception was found with 44 papers (8.6%). Crisis impacts involved 32 studies (6.3%), and crisis recovery was examined in 31 studies (6.1%). Further, fairly sufficient, 21 papers focused on crisis resilience (4.1%), 18 papers investigated crisis communication (3.5%) and 15 papers examined crisis response (2.9%). Disaster management/with multiple topics was studied by 20 papers (3.9%), and disaster recovery was investigated in 16 papers (3.1%). The areas worthy of significant note have collected even less than 10 papers in the study period, inclusive of crisis preparedness and prevention, learning, risk assessment and communication ( Table 6 ).

Crisis management research focus (N = 512).

The most explored research foci in the study period included crisis management/with multiple topics, risk management/with multiple topics, and disaster management (event). Crisis impact and crisis recovery, as well as risk perception also involved more than 30 papers respectively, that can represent the traditional focus of crisis management research at the theoretical level. The COVID-19 theme has more than 70 papers published (N = 79) in 2020, which surprisingly made it as one of the top ranking research themes in the summary. Its discussion will be presented in the next section involving the emerging research themes over the last decade (2010 to present).

3.4.1. Crisis management/with multiple topics

Crisis management has attracted academic attention for the entire study period. Anticipating crises and responding to them accordingly is crucial ( Henderson, 1999a ). A crisis or disaster management framework based on the model by Fink (1986) was proposed. Six elements of responses were suggested: precursors, mobilisation, action, recovery, reconstruction and re-assessment, and review. Risk assessment and disaster contingency plans were provided ( Faulkner, 2001 ). The crisis management framework of Ritchie (2004) follows the prescriptive model Richardson (1994) applied on the tourism industry: pre-crisis; crisis event and post crisis. This ‘one size fits all’ approach might cater to all sudden events ( Speakman & Sharpley, 2012 ).

By contrast, chaos theory assumes a random, complex and dynamic situation. That theory was used to explain the Mexican H1N1 crisis. Companies in the tourism industry operate in a relatively stable situation but are subject to unexpected attacks. The trigger case in Mexico is an outbreak of the H1N1 disease ( Coles, 2004 ; Speakman & Sharpley, 2012 ).

Co-management's characteristics ‘have been identified in the literature: (1) pluralism, (2) communication/negotiation, (3) transactive decision-making, (4) social learning, and (5) shared action/commitment’ ( Pennington-Gray et al., 2014a , 3). That management refers to combining resources from various stakeholders in the community for crisis management ( Pennington-Gray et al., 2014a ).

Researchers neglected crisis preparation and organisational learning in the tourism industry ( Clements, 1998 ; Cheung & Law, 2006 ; Anderson, 2006 ). In practice, large companies do have crisis management plans, unlike small business and tourism operators ( Cushnahan, 2004 ; Gruman et al., 2011 ).

3.4.2. Crisis impact

The Asian financial crisis and global economic crisis of 2008/09 affected the tourism industry ( Boukas & Ziakas, 2013 ; Henderson, 1999c ; Jones et al., 2011 ). In these events, people generally lost their spending power. If a host country suffers from a domestic crisis, then it usually attracts more visitors from other countries because of devaluation of the host country's currency ( Khalid et al., 2020 ). The lower demand for local tourism is counter-balanced by the arrival of more international tourists.

Usually, crisis impact could be measured by the drop of the number of inbound or outbound tourists and the spending of visitors ( Jin et al., 2019 ; Khalid et al., 2020 ; Wang, 2009 ). In turn, the impact would be reflected by economic indicators, such as the unemployment rate of the tourism industry ( Blake & Sinclair, 2003 ). People must also be convinced that everything is back to normal before they travel again.

The studies concentrated on sales loss and the drop in customers ( Jones et al., 2011 ; Liu, 2014 ). Financial ratio analysis is more objective but usually cannot capture instant impacts. Few investigations employed stock price to measure the effect of crises. Abnormal returns were a good indicator of the future earnings of a listed company ( Seo et al., 2014 ). Another dimension is the emotional aspect. Anger and outrage are emotional responses from customers. These reactions produce intangible effect on corporations ( Coombs & Holladay, 2010 ).

Aside from the economic impact, environmental and social cultural impacts must also be considered. For instance, the natural environment is vulnerable to disaster risks. Pollution problems could also affect the image of a city such as Beijing ( Tsai et al., 2016 ). From a social cultural perspective, local culture should be protected and revived.

3.4.3. Crisis recovery

The process wherein tourism operators' attempt to return to normal business and achieves good economic performance after a crisis is called crisis recovery ( Coombs, 2019 ). Various crisis recovery approaches were proposed. Restoration of confidence, media role, other stakeholder support and speed of the response are critical success factors for crisis recovery ( de Sausmarez, 2007a ). Analysis of the crisis, audience and place must be conducted before formulating a media strategy. The message source, target audience and the message itself are essential features for designing the media strategy in attempt to repair the image of the place ( Avraham & Ketter, 2017 ). In summary, image recovery is vital ( Ryu et al., 2013 ).

Other than media strategy, turnaround strategies usually entail increasing income and decreasing cost ( Campiranon & Scott, 2014 ). Price discount appears to be a common recovery strategy applied in the hospitality and tourism industry ( Kim et al., 2019 ; Okuyama, 2018 ).

A marketing program is a usual tactic in crisis recovery ( Carlsen & Hughes, 2008 ; Chacko & Marcell, 2008 ; Ladkin et al., 2008 ). Celebrity endorsement was also one of the best ways for implementing recovery marketing plans. Marketing campaigns should be continued after a crisis ( Walters & Mair, 2012 ). Some researchers expressed reservations about marketing programs. They instead prefer a demarketing approach if the place was seriously damaged and remains unsafe for visitors ( Orchiston & Higham, 2016 ).

3.4.4. Risk management/with multiple topics

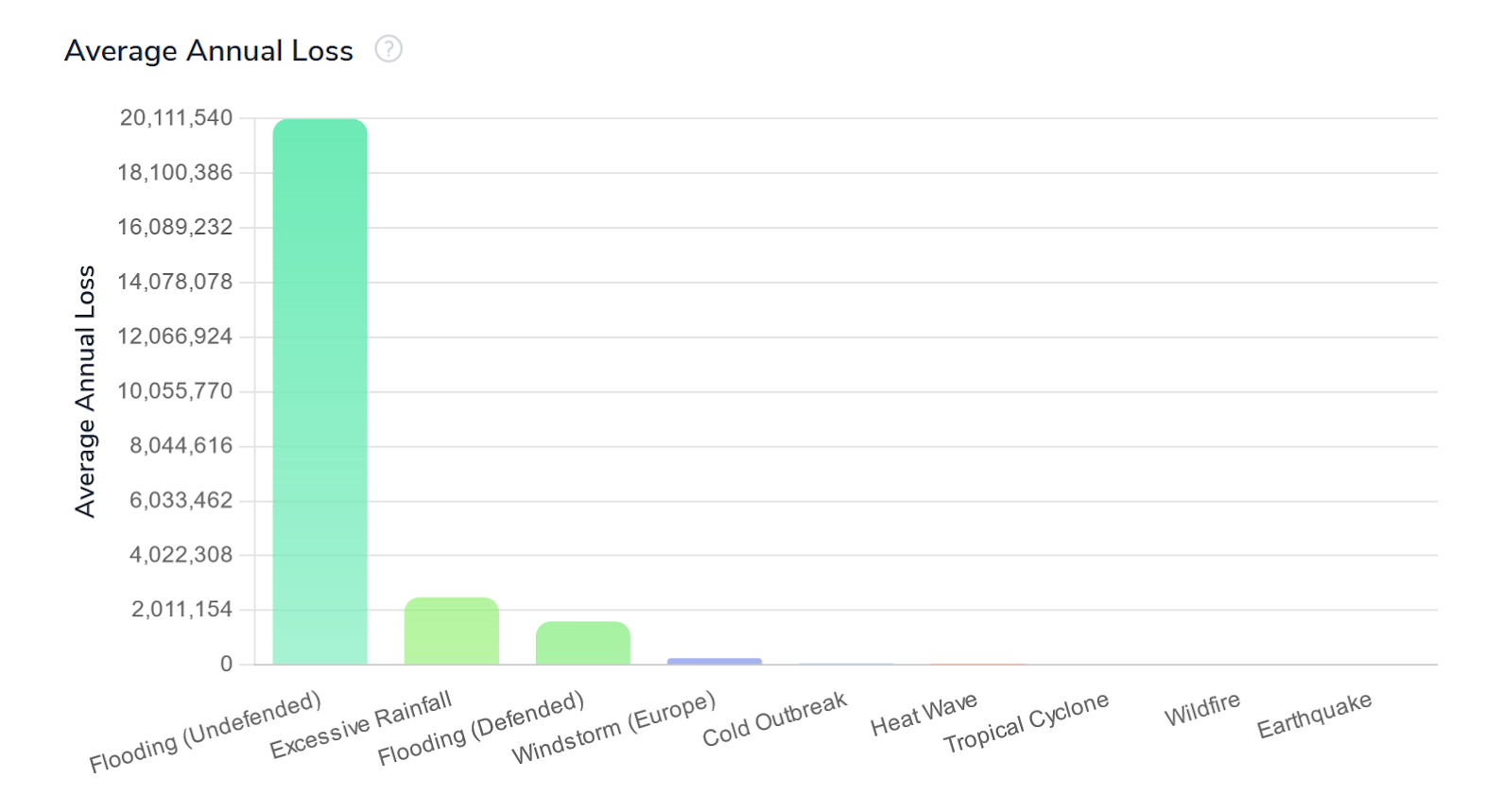

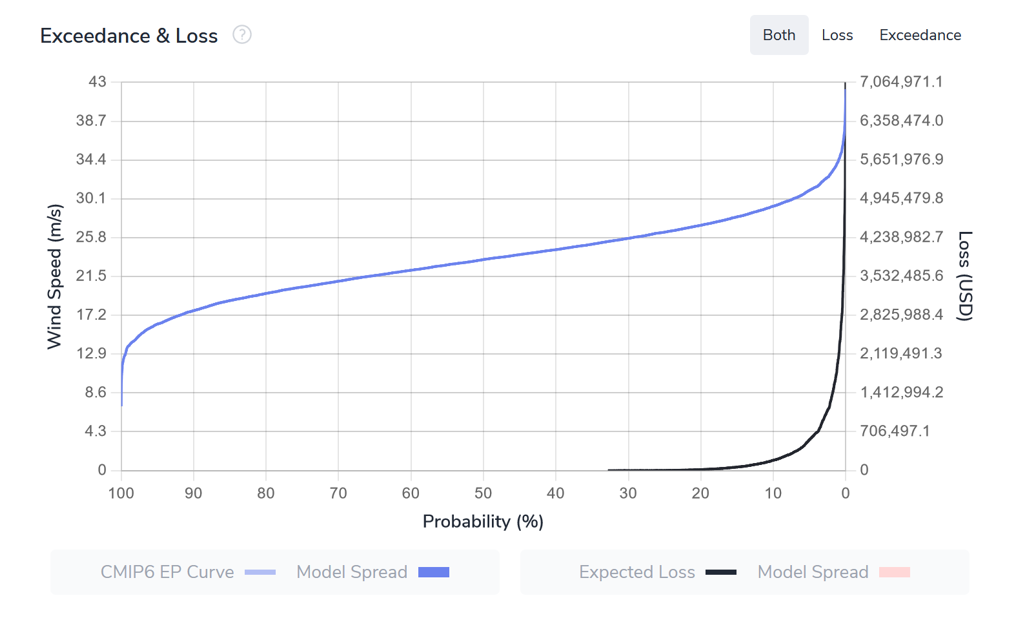

Risk management is important for business operations ( Bharwani & Mathews, 2012 ). However, different companies may present different levels of risk appetite in terms of their willingness to manage risks ( Zhang, Paraskevas, & Altinay, 2019 ). The main types of business risks include operating risks, strategic risks and financial risks ( Harland et al., 2003 ). Financial risks can be categorised as systematic (common to whole economy) and unsystematic risks (firm-specific) ( Chen, 2013 ). According to Oroian and Gheres (2012) , all internal risks (e.g. organisational risks) and external risks (e.g. nature, competitiveness, economic, political and infrastructure risks) should be considered. Chang et al. (2019) found that financial risks, competing risks and supply chain risks may be classified as high priority by the travel industry.

Given the nature of the industry, hospitality and tourism companies may possibly face more particular environmental risks ( Böhm & Pfister, 2011 ; Cunliffe, 2004 ; Hillman, 2019 ), such as the weather conditions and climate change ( Ballotta et al., 2020 ; Bentley et al., 2010 ; Córdoba Azcárate, 2019 ; de Urioste-Stone, 2016 ; Hopkins & Maclean, 2014 ; Steiger et al., 2019 ; Tang & Jang, 2011 ), which will result in financial risks ( Franzoni & Pelizzari, 2019b ) and other types of business risks for companies.

Regarding risk management and practices, various risk mitigation and reduction strategies have been studied. Loehr (2020) proposed a Tourism Adaptation System for this purpose. Portfolio analysis was adopted for risk reduction and management in the industry ( Minato & Morimoto, 2011 ; Tan et al., 2017 ). The scenario planning approach was also employed by Orchiston (2012) for risk forecasting. Safety and security measures, through security checkpoints, security systems and procedures, are of vital importance in operational strategies ( Daniels et al., 2013 ; Peter et al., 2014 ). However, Rantala and Valkonen (2011) argued that safety issues in the hospitality and tourism industry are complex because of the infrastructure and technology, lack of experiences for customers and employees, and the safety culture in the industry. Vij (2019) examined the views of senior managers in the hospitality industry and highlighted the urgent safety need regarding cyberspace and data privacy. Stakeholder collaboration might be also considered for sharing the responsibility in risk management ( Gstaettner et al., 2019 ). As for the aspect of risk transfer, insurance contracts ( Dayour et al., 2020 ; Franzoni & Pelizzari, 2019a ) is a traditional focus for mitigating the negative impacts through transferring the risks to third parties. Nevertheless, that approach was not a common practice in the industry ( Waikar et al., 2016 ).

3.4.5. Risk perception

This work found that many risk perception-focused studies were conducted in the tourism context. Mass tourists are generally risk adverse in unfamiliar surroundings. The risks related to health, crime, accident, environment and disasters greatly affect the tourists' decision-making ( Carballo et al., 2017 ; George, 2010 ; Hunter-Jones, 2008 ). Some studies categorised those risks into physical, financial, psychological and health risks ( Jalilvand & Samiei, 2012 ; Sohn & Yoon, 2016 ). According to Carballo et al. (2017) , some risks for tourists can be controllable (e.g. illness and sunburn), whereas others are not.

The causes leading to the risk perceptions of tourists included demographic (e.g. age and nationality) and individual trip-related characteristics (e.g. visit purpose and frequency of travel) ( George, 2010 ; Jalilvand & Samiei, 2012 ), past experiences ( Schroeder, Pennington-Gray, Donohoe, & Kiousis, 2013 ), marketing communications ( Lepp et al., 2011 ; Liu-Lastres et al., 2020 ), media effects ( Kapuściński & Richards, 2016 ; Rashid & Robinson, 2010 ), mega-events, such as the FIFA World Cup) ( Lepp & Gibson, 2011 ) or Olympic Games ( Schroeder, Pennington-Gray, Donohoe, & Kiousis, 2013 ), as well as the destination risk management measures ( Toohey et al., 2003 ). Different directions of research or research findings were noted. Rashid and Robinson (2010) believed that the media effects exaggerated the risk perceptions. Kapuściński and Richards (2016) found that the media could either amplify or attenuate risk perceptions. George (2010) and Jalilvand and Samiei (2012) tended to compare the tourists' gender, age and trip-related characteristics for risk perception, but the latter study found more obvious difference among the groups.

Risk perceptions were also found to negatively impact various constructs. However, the dependent variables were overwhelmingly concentrated on destination image ( Chew & Jahari, 2014 ; Lepp et al., 2011 ; Liu-Lastres et al., 2020 ; Sohn & Yoon, 2016 ) and revisit intention ( Chew & Jahari, 2014 ; George, 2010 ; Zhang, Xie, et al., 2020 ). Other outcomes of risk perception, such as tourist hesitation ( Wong & Yeh, 2009 ), destination attitude ( Zhang, Hou, & Li, 2020 ), satisfaction and trust ( Wu et al., 2019 ), emotion ( Yüksel & Yüksel, 2007 ), recommendation to others ( George, 2010 ), decision-making process ( Taher et al., 2015 ) and travel behaviour modification ( Thapa et al., 2013 ), were also investigated.

Note that tourists may be motivated by risk-taking behaviours ( Cater, 2006 ; Chang, 2009 ). These tourists possibly favour novelty and adventurous tourism activities. Examples of risk-taking contexts in the hospitality and tourism industry include gaming ( Chang, 2009 ), mountain climbing ( George, 2010 ; Probstl-Haider et al., 2016 ) and other adventurous activities ( Cater, 2006 ). Pröbstl-Haider et al. (2016) indicated that the risk-taking behaviour may be attributed to the tourists' experience, participation frequency and commitment, their risk perceptions and the individual trade-off of risks.

3.4.6. Disaster management/disaster event (description)

This study consolidated disaster management and disaster event (description) into one generic category for subsequently summary and discussions. Following previous classical literature on disaster management ( Faulkner, 2001 ; Prideaux et al., 2003 ), disasters can be considered as unpredictable or unprecedented crisis situations with great complexity and gravity. Ritchie (2008) summarised the many natural disasters frequently studied in tourism literature as comprising hurricanes, flooding and tsunami, earthquake, biosecurity and diseases (e.g. foot and mouth disease and SARS). Huan et al. (2004) dubbed these incidents as ‘no-escape’ disasters.

As a result of the disasters, tourist fatalities may occur while the destination and business facilities are severely devastated ( Cohen, 2009 ). Different hospitality and tourism sectors may experience remarkably varied challenges ( Henderson, 2007 ). Previous literature also recorded a comparison across disasters for certain destinations ( Prideaux, 2003 ) or for the investigation of disasters across different destinations ( Bhati et al., 2016 ). Many studies focused on business and destination resilience ( Bhaskara et al., 2020 ; Bhati et al., 2016 ; Filimonau & De Coteau, 2020 ; Ghaderi et al., 2015 ; Lew, 2014 ). Hospitality and tourism business normally react without warning, deal with existing staff, reduce salaries over the short-term and consider rebuilding tourist confidence over the long-term ( Henderson, 2005 ). Filimonau and De Coteau (2020) emphasised that the destinations studied fail to react effectively. Ghaderi et al. (2015) found that the primate enterprises lacked knowledge and analysis of disasters to prepare for the future.

Faulkner (2001) presented a tourism disaster management framework that incorporated six stages: pre-event, prodromal, emergency, intermediate, long-term recovery and resolution. He suggested destination marketing and communications, risk assessment, disaster management teaming and disaster contingency plans as examples of management strategies. This seminal model was applied for different disaster case studies ( Faulkner & Vikulov, 2001 ; Miller & Ritchie, 2003 ). Walters and Clulow (2010) examined previous literature and indicated that disaster-recovery marketing may be ineffective for areas affected by disasters. By contrast, Biran et al. (2014) argued that even disaster attributes can possibly motivate certain future tourists.

4. Discussion on emerging research themes from 2010 to present

In Fig. 1 , the Y-axis showcases the number of publications that studied crisis management in the hospitality and tourism industry. The X-axis records the years. Obviously, an increasing trend occurred for the relevant publications over the past 36 years. Five distinct peaks were identified in these publication waves: the years 1999, 2008, 2013, 2017 and 2020. Publishing an academic paper usually takes two to three years from the start of an initial idea. In many cases, researchers can only observe impacts and report their findings several years after a crisis event, for example, during the Asian financial crisis in 1997 and the wars in 1990s (including the Gulf War, 1990–91; Croatian War, 1991–95; Bosnian War, 1992–95 and the Afghan War, 1990–2001). Studies published in 1999 mainly involved the financial crisis and the terrorism at that time. However, the papers recorded in 2008 included the impacts of the 9/11 terrorist attack in 2001. Papers in the year 2013 were mostly related to the financial crisis which dated back to 2007 and 2008. Papers with political topics were published in 2017/18. Many COVID-19 papers were published in 2020. Four major themes emerged in the last decade (year 2010-present), namely the health-related crisis, social media, political disturbance and terrorism crises ( Table 7 ).

Research areas for crisis management studies in last decade (Year 2010 to Present).

4.1. Health-related crisis (including COVID-19)

The 2006 Avian Flu, Year, and the 2003 SARS, the 2001 Foot and Mouth disease are notable health-related crisis events that impacted the hospitality and tourism industry ( Baxter & Bowen, 2004 ; Chien & Law, 2003 ; Page et al., 2006 ; Tew et al., 2008 ). Further, 284,00 deaths were recorded in the 2009 Swine flu. Tourism loss was US$2.8 billion ( Rassy & Smith, 2013 ). Recent case of health-related crisis event is the Ebola outbreak in 2014 and 2015. The outbreak affected the Africa tourism industry by 5% revenue reduction in year 2015 ( Novelli et al., 2018 ). Lyme disease was studied from the perspective of tourism management ( Donohoe et al., 2015 ). The impact of Zika outbreak for 2016 in Latin America and the Caribbean caused losses of US$3.5 billion in tourism industry; and no vaccine is available ( World Bank, 2016 ). In the same year, the global outbreak of Dengue fever led to even severe economic impact of US$8.9 billion ( Shepard et al., 2016 ). The recent global outbreak of COVID-19 in 2020 is undeniably a vastly emerging research focus. An overview of health-related events has been presented by Hall et al. (2020) .

Large number of papers in COVID-19 has been published within a short period of time. Most of the papers tended to study the impacts of COVID-19 in hospitality and tourism industry ( Bulin & Tenie, 2020 ; Jaipuria et al., 2020 ; Knight et al., 2020 ; Qiu et al., 2020a , b ; Seraphin, 2020 ; Uğur & Akbıyık, 2020 ), some of which focused on particularly the hotel industry ( Bajrami et al., 2020 ; Vo-Thanh et al., 2020 ). Besides, some provided directions for recovery ( Yeh, 2020 ). For instance, using a private dining room or table could be one of the solutions in restaurant industry ( Kim & Lee, 2020 ). Resilience is another topic of discussion ( Butler, 2020 ). Rittichainuwat et al. (2020) found that the Thai hospitality, bleisure (business and leisure) and international standard venues are key factors for resilience of the exhibition industry. For tourism industry, travel after pandemic is arguably associated with protection motivation and pandemic travel fear ( Zheng et al., 2021 ).. Research topics could be about perceived risk and tourist decision making ( Matiza, 2020 ). In terms of the research methodologies in this research theme, most of the papers appeared to be conceptual papers ( Baum & Hai, 2020 ; Bausch et al., 2020 ; Haywood, 2020 ; Li et al., 2020 ; Zenker & Kock, 2020 ). A few qualitative studies used in-depth interview ( Awan et al., 2020 ; Loi et al., 2020 ) while some others adopted case studies ( Breier et al., 2021 ; Neuburger & Egger, 2020 ). Quantitatively, some relied on online survey ( Karl et al., 2020 ) or telephone survey ( Pappas & Glyptou, 2021 ) due to pandemic constraints.

Without effective crisis management in this regard, the entire hospitality and tourism industry could hardly recover by rebuilding tourists and guests' confidence who suffer from health-related crises, with no exception of COVID-19. According to Coombs (2019) , there are four stages in crisis management: crisis prevention, crisis preparation, crisis response and crisis recovery. The purpose of crisis prevention is to detect warning signals and to stop any possible negative events. Certain disasters cannot be prevented even for early preparation. Crisis management plan needs to list out every step we need to follow when crisis happens. A team can be organised beforehand to carry out some rehearsals regularly. Immediate, transparent and consistency are the basics in preparing crisis response. In post crisis period, people need to learn from the past, including the mistakes made. Business continuity plan guides us to recover from crisis quickly ( Coombs, 2019 ; Fung et al., 2020 ). These should be the basics of lessons for effective crisis management derived from the different health-related crisis events in history and the COVID-19 outbreak as well. All stakeholders should consolidate their knowledge and experiences to better prepare for the future.

4.2. Social media theme

Over the past decade, companies in the hospitality and tourism industry have greater attention to the use of social media in practice. Social media can distribute news over distances within a short period of time. That media could co-ordinate with different stakeholders in crisis events ( Antony & Jacob, 2019 ; Maia & Mariam, 2018 ). Meanwhile, a wide range of stakeholders (i.e. individual customers, governmental bodies, activist groups, rescue teams, consumers' bodies, mass media and others) can take part in management through social media ( Sigala, 2012 ). Zeng and Gerritsen (2014) summarised the social media research in tourism and highlighted clearly (p.34) that ‘giving its mobility and facility for instant interaction, social media can be expected to play a more important role in tourism destination management, particularly in crisis management … ’ Sigala (2012) further revealed that social media can be utilised throughout the different stages of crisis management involving mitigation, preparedness, response and recovery. For example, Schroeder and Pennington-Gray (2015) studied the effect of social media in crisis communications. Travellers may possibly refer to feedback from social media in search of related information when a crisis occurs. Instead of discussing crisis impacts on tourism sectors in Hong Kong, researchers attempted to focus on the crisis communication through social media which affects social media users' subsequent attitude ( Luo & Zhai, 2017 ). Social media can also be used in the revision stage to develop resilience and adaptability. Moreover, social media has employed in fundraising events and in creating emotional support after crisis ( Coombs, 2019 ).

4.3. Political disturbances theme

The past decade witnessed a few examples of political disturbances or social movements ( Monterrubio, 2017 ). In Thailand, Cohen (2010) examined the sources of airport occupation. The occupation was a social movement opposed to the Thailand government. The movement changed the safety destination perception of Thailand and affected the tourism industry in the long term ( Cohen, 2010 ). In Hong Kong, the ‘yellow vest’ movement occurred on November 17, 2008. Protesters decided to continue to protest every Saturday. That situation might generate an unsafe image for incoming tourists ( Derr, 2020 ). A political event called Occupy Central in 2014 and 2015 in Hong Kong also requested for the election of a Chief executive. ‘Central’ is a place in Hong Kong that encompasses many important business and government offices. Another social movement involved Hong Kong's anti-extradition law amendment bill in 2019. These occurrences strongly impact the peaceful image of Hong Kong.

4.4. Terrorism theme

Unquestionably, the hospitality and tourism industry is vulnerable to terrorism. Tourists might possibly switch to other travel destinations because of perceived terrorist threats to their intended destination ( Sönmez et al., 1999 ; Walters et al., 2019 ). Terrorism has become a popular theme of research since 2001, when the terrorist attack of historic significance occurred on 11 September in the U.S. ( Evans & Elphick, 2005 ; O'Connor et al., 2008 ; Taylor, 2006 ; Yu et al., 2005 ). |Another example involves the targeting of Bali tourists by Al Qaeda in 2002 ( Xu & Grunewald, 2009 ).

Some terrorism-related studies from past decade focused on the hotel industry. One research indicated that terrorism affects the brand image of a local hotel if an attack from terrorists occurs on the destination. Thus, protecting the brand equity is an effective strategy ( Balakrishnan, 2011 ). Another paper compared the impacts of 9/11 on hotel room demand to those during the financial crisis of 2008 ( Kubickova et al., 2019 ). Stahura et al. (2012) emphasised that crisis management planning is essential when the industry confronts potential crisis from terrorist attacks.

5. Research opportunities

Following a systematic analysis of traditional research focuses over the 36 years and emerging research themes over the last decade, a new conceptual framework was presented in Fig. 4 to highlight the proposed future research directions of crisis management in the hospitality and tourism industry. Further research areas were identified using a TCM (Theory-Context-Method) model ( Paul et al., 2017 ) presented in three layers.

Conceptual framework for future research of crisis management in hospitality and tourism industry.

The outer layer related to the crisis management at the theory level. Traditional research foci at the theoretical level appear to include crisis management/with multiple topics, crisis impact, crisis recovery, risk management/with multiple topics and risk perception and disaster management. Unfortunately, little attention has been paid to crisis management education and training, a feature which was rather regarded as the most effective method of crisis management in the long run for the tourism industry ( Henderson, 1999a ). The literature review also entailed relatively less academic attention to crisis prevention and preparedness, risk assessment and risk communication. In the second inner layer, proposed contexts of crisis management research were presented. The health-related crisis events including COVID-19, data privacy, digital media, political-related crisis events as well as other less explored contexts are suggested for the future research of crisis management in the hospitality and tourism industry. It should be noted further that the health-related, data privacy and political-related crisis events are also related to the digital media area. This situation indicates that the transmission of crisis information is rather faster than ever before through digital media, so that management of various crises should be examined in this era of digital media. Meanwhile, the less explored industry sectors and contexts should be studied. The core and the inner layer suggest adopting new analytical research methods for designing various research and analysing related data. The following will detail the proposed future research areas and identify specific research questions for the benefit of future researchers ( Table 8 ).

100 specific future research questions in the ten future areas.

5.1. Theory development

Fink (1986) 's four stage model is influential in crisis management studies. His four-stage model was applied in diseases (1) prodromal, hints of potential crisis; (2) breakout; (3) chronic, the effect of crisis persists; (4) resolution, some clear signals the crisis is no longer a concern ( Fink, 1986 ). The other influential model is from Mitroff (1994) . His five stages model turns Fink's descriptive model to prescriptive approach. Crisis management efforts was divided into five phases: signal detection, prevention, damage containment, recovery and organisational learning ( Mitroff, 1994 ). Faulkner (2001) made a good comparison of the models. In fact, previous research have also indicated the cycling loop of crisis management ( Xu & Grunewald, 2009 ). For instance, Pursiainen (2018) explicitly explained the crisis management circle with some suggested procedural steps (prevention, preparedness, response, recovery, learning, risk assessment). This further provides the solid theoretical foundation for Fig. 4 that the proposed future research areas at theoretical level stay at different cycling stages in crisis management: from crisis prevention and preparedness to risk communication to crisis management education & training, and then to risk assessment, which has been also considered to pave the way for the next round of crisis prevention and preparedness.

5.1.1. Crisis prevention and preparedness

Papers on crisis preparedness (9 papers) and crisis prevention (7 papers) are notable fewer. In fact, preventing the crisis from happening is the best crisis management strategy. Crisis preparedness takes up most of a crisis manager's time ( Coombs, 2019 ; Pforr & Hosie, 2008 ). The recovery and experiences of crisis handling of one time can be translated into the crisis preparedness and precaution measures for the potential next time. The awareness and recognition of possible crises by managers and staff can be strategically important throughout the learning process and crisis management cycle ( Xu & Grunewald, 2009 ).

5.1.2. Risk communication

Compared to the risk management (68 papers) and risk perception (41 papers) categories, prior literature records only one paper ( Heimtun & Lovelock, 2017 ) which focused on ‘risk communications.’ Risk communication is indeed important in the hospitality and tourism industry. An uncertainty always exists because of the weather or some other uncontrollable factors. Risk communication is important when they promote tourism products to prospective customers ( Heimtun & Lovelock, 2017 ). It also relates to legal issues. For example, travel companies and tour organisers should explicitly explain to potential tourists the types of risks involved and tourists (risk bearers) could also express their concerns and fears about the risks in the process of their decision making. The outcomes of risk communication are expected to enhance customers' risk awareness and help them take personal proactive actions. The appropriate overestimation of risk can be also effective for helping consumers make decisions while avoiding possible legal risks ( Coombs & Holladay, 2010 ).

5.1.3. Crisis management education and training

Special attention should also be given to crisis management education and training in hospitality and tourism-related programmes. In the ever-increasingly diversified and changing market, hospitality and tourism companies have an urgent need of specialists and professionals in crisis management for their sustainable and healthy business development. Graduates equipped with relevant knowledge and working experiences will be highly needed by the industry. The presence of an experienced leader and crisis team consisting of qualified staff can be strategically significant in the different stages of crisis management in the tourism industry ( Ritchie, 2004 ). Surprisingly, scare research exists in this regard.

In this study, the US, Australia and the UK were well represented in terms of the leading authors of crisis management studies in the hospitality and tourism industry. Academic platforms may favour more interested researchers in this area who originate from other places. The cross-cultural approach is also strongly recommended for systematic comparisons of the findings generated from different cultural backgrounds. Future research could be extended to more developing countries, such as China and Vietnam, to compare their crisis prevention measures.

5.1.4. Risk assessment

Less than 10 papers focused on risk assessment, a figure which could suggest a future research direction. Undeniably, hospitality and tourism companies may be interested in identifying the possible risks according to their frequency, scale and level of loss, and assess their influences for developing effective risk management strategies ( Tsai & Chen, 2010 ). Roe et al. (2014) summarised many methodological approaches that are currently adopted to assess and manage the various risks, particularly environmental ones. They exemplified with the Environmental Impact Assessment, Environmental Audit and Ecological Footprint with support of Delphi Technique. In fact, tourists can also learn from the risk assessment results to manage their holiday travel plans and decide insurance purchase ( Olya & Alipour, 2015 ). However, as each assessment methodology has its own merits as well as limitations, methodological innovations and comprehensive assessment models are expected for future research, particularly in the hospitality and tourism context owing to the lack of research output in this regard ( Tsai & Chen, 2010 ).

5.2. Context

5.2.1. covid-19 (coronavirus disease 2019).

COVID-19 has threatened the lives and health of people globally and seriously disrupts the traffic flow of people worldwide. Hotels, travel agencies, airlines and all sorts of related industries face a serious challenge in 2020 ( Gössling et al., 2020 ; Qiu et al., 2020a , b ). In fact, the world may see a co-occurrence of various health risks and diseases in future. With lessons derived from COVID-19, health-related crisis management could be a universal issue.

The COVID-19 pandemic may not be over in year 2021 although different vaccines are available. Tourism and hospitality industry will still be seriously affected. Firstly, the impacts on the industry have already been estimated for the year 2020.70% of hotel employees have been laid off and 4.6 million supporting jobs was lost in United States ( American Hospitality and Lodging Association, 2020 ). The forecasted impacts for the year 2021 are still in progress and not yet available. Secondly, there could be new models for people travelling for leisure or business after the pandemic. Thirdly, new business model may evolve for the hotel, airlines, catering, or even the sharing business ( Farmaki et al., 2020 ).

5.2.2. Data privacy in hospitality and tourism

Today, most organisations are using information technology as a main or supplementary tool for their business operations and management. Extensive organisational/customer sensitive information is stored and/or processed in digital format, particularly when using social media for communications. Loss of confidential information would be disastrous for a company. Note that any inappropriate processing of such sensitive and personal information may cause great damage to organisational reputation with the expected decline of customer trust and loyalty ( Watson & Rodrigues, 2018 ). This fact was highlighted with no exception in the hospitality and tourism industry ( Chen & Jai, 2019 ). Unfortunately, very few papers have addressed this issue. Chen and Jai (2019) explored a research agenda to examine the relationship between data breach or privacy issues and customer relationship building and loyalty. They also suggested checking the different levels of privacy concerns by customers and their impacts.

5.2.3. Political-related crisis events

Many political-related crisis events also have impacts on hospitality and tourism industry. For example, in a historical sense, the US-Iran conflict has long influences over the development of Iran's tourism industry ( Estrada et al., 2020 ; Khodadadi, 2018 ). Recently, the Hong Kong extradition bill controversy (2019–2020) also shook Hong Kong's society and the tourism industry in particular ( Lee, 2020 ). More researchers are expected to express interest on these cases to discuss different research questions. These cases are related to risk and crisis management for destination marketers and various stakeholders. However, the natures of these circumstances vary, a situation which could possibly generate dissimilar research findings and shed light in the crisis management field. Future researchers could investigate the effects of crisis types on crisis management with case studies of new crisis events ( Coombs, 2019 ).

5.2.4. Digital media theme

Digital media plays a major role in future. People may like to use social media more often to express and share their views. However, a crisis may occur for the companies that fail to adequately manage the social communications of their products and brands. For example, customers may complain on social media. How the complaint is transmitted through the Internet and the responses from the organisation are rather practical topics for researchers. Ryschka et al. (2016) is one of the few to explore how a company's response to a crisis raised on social media affects its reputation. Their results showed that the speed of response is important as well as the brand familiarity and cultural values. Unfortunately, their research context (cruise industry) has its special nature and may not be applicable to other industry sectors or businesses at large. Sigala (2012) indicated that future studies could analyse role of social media in crisis communications and its impacts on organisation image. The factors that contribute to the motivations and barriers of using social media by companies can also be studied accordingly ( Sigala, 2012 ). Luo and Zhai (2017) highlighted the need for further research about cyber nationalism and bilateral relationships concerning the tourism boycott and destination crisis.

5.2.5. Other less explored contexts

Most of the reviewed crisis management studies focused on hotels as a sector of the hospitality and tourism industry. Studies should be more diversified across other sectors of the industry. Certain hospitality and tourism industry sectors are under-explored, including airlines, travel agencies, restaurants, the conference sector, ocean cruising, theme parks and wellness spas. For instance, any destination and tourism crisis may affect tour operators and travel agencies which play an important role in tourism flows ( Cavlek, 2002 ). Emphasis on tour operators is suggested for their strategic importance towards destination recovery in the post-crisis period ( Cavlek, 2002 ). The airline industry is also very sensitive to economic downturns and global crises ( Hatty & Hollmeier, 2003 ). Accordingly, the companies involved in that industry may be unable to adjust immediately when facing declining demands in the market. Sangpikul and Kim (2009) identified different factors of barriers affecting the convention and meeting industry. For example, they revealed political unrest as the source of crisis for the MICE (Meeting, Incentive, Conventions and Exhibitions) industry. However, few studies have investigated this sector.

Previous crisis management research relied on traditional methodologies including case studies, content analysis, descriptive analysis and regression analysis ( Table 5 ). Researchers could consider analysing images and/or pictures of the crisis event. Case study in crisis research usually involves with very small sample size. Two diseases cases (SARS and H1N1) were covered in a crisis management study ( Fung et al., 2020 ). Generalization of a case study usually is a difficult task for researcher. Thus, case study sometimes was conducted by way of an exploratory study; or simply used to test a pre-established theory. Besides, case study would also be used to demonstrate a good crisis management practice and propose a relationship or association among variables ( Eisenbhardt, 1989 ). As a whole, case study is a perfect choice to explain and answer the questions on “how” and “why”.

Researchers can consider qualitative comparative analysis. In literature, less than one percentage of crisis management articles used qualitative comparative analysis (see Table 5 ). Most of the focal researches examined relationships among variables in a linear manner using regression analysis and ignored the complexities that might possibly exist across the variables. Even in the case of low level of multi-collinearity, one variable might depend on the other explanatory variable ( Woodside, 2013 ). Often, the impacts on tourism due to crisis might not work in a linear relationship. The qualitative comparative analysis can be a suitable analysis method ( Papatheodorou & Pappas, 2017 ).

5.9 percent or thirty of crisis management papers adopted structural equation modelling as their main analysis method ( Table 5 ). Partial Least Squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) has not been used extensively in particular hospitality and tourism research but rather preferred in marketing and management studies in general ( Ali et al., 2018 ). Conceptually, PLS has some advantages including smaller sample size and less restricted data normality requirement. For example, with 5% significant level, minimum R-square 10% and number of arrows pointing at a construct is five, 150 samples is sufficient ( Hair et al., 2019 ). This fits the current research situation under pandemic concerns that achieving big sample size may not be an easy task. Moreover, models in risk perception sometimes evolve more than one dependent variable and some other mediating or moderating variables, such as perceived security, perceived risk, destination image or willingness to visit ( Zenker et al., 2019 ). Complex predicting model could be handled by PLS easily.

Conjoint analysis is sometimes used in hospitality research. For example, it could explain how tourists choose a particular hotel. It depends on a lot of considerations at the same time. Costs, time, word-of-mouth, activities, past experience and so on are possible reasons ( Suess & Mody, 2017 ). Only a subset of combinations needs to be tested in the field in order to get the answer. In crisis management research, crisis response can be one of the possible topics using this method. For example, one has to take into account different factors before formally making an apology for a customer complaint. Possible factors can include seriousness of crisis, crisis history, and responsibility of company ( Coombs, 2019 ).

6.1. Specific future research questions