- Applying to Uni

- Apprenticeships

- Health & Relationships

- Money & Finance

Personal Statements

- Postgraduate

- U.S Universities

University Interviews

- Vocational Qualifications

- Accommodation

- Budgeting, Money & Finance

- Health & Relationships

- Jobs & Careers

- Socialising

Studying Abroad

- Studying & Revision

- Technology

- University & College Admissions

Guide to GCSE Results Day

Finding a job after school or college

Retaking GCSEs

In this section

Choosing GCSE Subjects

Post-GCSE Options

GCSE Work Experience

GCSE Revision Tips

Why take an Apprenticeship?

Applying for an Apprenticeship

Apprenticeships Interviews

Apprenticeship Wage

Engineering Apprenticeships

What is an Apprenticeship?

Choosing an Apprenticeship

Real Life Apprentices

Degree Apprenticeships

Higher Apprenticeships

A Level Results Day 2024

AS Levels 2024

Clearing Guide 2024

Applying to University

SQA Results Day Guide 2024

BTEC Results Day Guide

Vocational Qualifications Guide

Sixth Form or College

International Baccalaureate

Post 18 options

Finding a Job

Should I take a Gap Year?

Travel Planning

Volunteering

Gap Year Blogs

Applying to Oxbridge

Applying to US Universities

Choosing a Degree

Choosing a University or College

Personal Statement Editing and Review Service

Clearing Guide

Guide to Freshers' Week

Student Guides

Student Cooking

Student Blogs

Top Rated Personal Statements

Personal Statement Examples

Writing Your Personal Statement

Postgraduate Personal Statements

International Student Personal Statements

Gap Year Personal Statements

Personal Statement Length Checker

Personal Statement Examples By University

Personal Statement Changes 2025

Personal Statement Template

Job Interviews

Types of Postgraduate Course

Writing a Postgraduate Personal Statement

Postgraduate Funding

Postgraduate Study

Internships

Choosing A College

Ivy League Universities

Common App Essay Examples

Universal College Application Guide

How To Write A College Admissions Essay

College Rankings

Admissions Tests

Fees & Funding

Scholarships

Budgeting For College

Online Degree

Platinum Express Editing and Review Service

Gold Editing and Review Service

Silver Express Editing and Review Service

UCAS Personal Statement Editing and Review Service

Oxbridge Personal Statement Editing and Review Service

Postgraduate Personal Statement Editing and Review Service

You are here

Communications, media and culture personal statement example.

I am hoping to read for a communications, media and culture degree. I find it remarkable, inspiring and a little bit frightening how the media exercise control over our lives, whilst offering rich cultural rewards. I am fascinated by the action and effects of human communications of all kinds and am keen to extend the insight I have gained so far. My interest in the subject began through my GCSE Media Studies and my knowledge of the subject area has expanded at A-level where I am acquiring analytical skills, helping me unpack and contextualise a wider variety of media forms. My other A-levels are English Language, Sociology, Critical Thinking and Philosophy &Ethics, and these are giving me a broad overview of life and human communications and culture. An example of how these subjects support each other would be studying the marxist concept of hegemony and applying it to religion, media ownership, the high culture/low culture debate in sociology and even the bourgeois emphasis on Standard English. I've slowly been gaining practical experience alongside my academic learning. Two years ago, I was lucky enough to get work experience with a television crew on location as a runner. I learnt the value of working as a member of the team in a stressful environment and I gained an understanding of the processes of TV production. I have also been involved in several other media projects, some as coursework and others undertaken independently. Coursework projects have included a magazine for young male teenagers; designing a product and advertising campaign; and producing, directing and presenting a documentary for sixth formers and their parents on the EMA system. As extra-curricular activities, I designed a poster and Internet campaign for one of the school plays and in the absence of any existing school publication, I launched a bimonthly newsletter, aimed at Angley's students. These projects have provided great learning experiences, enabling me to develop print software skills in a creative way. Other school activities have included, the lead male role in 'South Pacific' and significant roles in 'Oliver' and 'West Side Story' as well as assisting the Performing Arts A-level group perform their comedy show. By playing roles on stage, my confidence has increased and I have learnt to appreciate and learn from the talents of others. I am also a school prefect, which I find satisfying and a great privilege. In my leisure time I enjoy making films - mostly parodies of various genres. I then edit the films using a programme called Magix Movie Edit Pro. I have also edited on Final Cut Express, which has made an interesting comparison. My next project is to learn Final Cut Pro, and to develop a more effects-driven style. I also like to read, for example, I was inspired by Naomi Klein's book No Logo on the effects of globalization, the commoditisation of our culture and public spaces and how powerful brands have become. I am currently reading Graeme Burton's Media & Society to gain some additional perspective on my A2 media and to prepare myself for my degree. So far I have enjoyed myself in my studies and hopefully have developed some of the skills and qualities for success in degree-level communications, media and culture studies.

Profile info

This personal statement was written by Superboy for application in 2008.

Superboy's Comments

It's okay i guess, it pretty much describes me not trying to sound big headed, i tried to show what i wanted to gain from going to university and what skills i have and how they can become much better by going to the right university. The key was 'Show don't tell'.

Related Personal Statements

Not at all interesting.

Wed, 23/09/2009 - 04:00

not at all interesting begining

yeah, loved it! lol!

Fri, 16/10/2009 - 14:25

(No subject)

Wed, 12/10/2011 - 19:33

Add new comment

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

31 Cross-Cultural Communication

What is culture.

Learning Objectives

Upon completing this chapter, you should be able to:

- distinguish between surface and deep culture in the context of the iceberg model,

- describe how cross-cultural communication is shaped by cultural diversity,

- explain how the encoding and decoding process takes shape in cross-cultural communication,

- describe circumstances that require effective cross-cultural communication, and

- describe approaches to enhance interpersonal communication in cross-cultural contexts.

We may be tempted to think of intercultural communication as interaction between two people from different countries. While two distinct national passports communicate a key part of our identity non-verbally, what happens when two people from two different parts of the same country communicate? Indeed, intercultural communication happens between subgroups of the same country. Whether it be the distinctions between high and low Germanic dialects, the differences in perspective between an Eastern Canadian and a Western Canadian, or the rural-versus-urban dynamic, our geographic, linguistic, educational, sociological, and psychological traits influence our communication.

Culture is part of the very fabric of our thought, and we cannot separate ourselves from it, even as we leave home and begin to define ourselves in new ways through work and achievements. Every business or organization has a culture, and within what may be considered a global culture, there are many subcultures or co-cultures. For example, consider the difference between the sales and accounting departments in a corporation. We can quickly see two distinct groups with their own symbols, vocabulary, and values. Within each group there may also be smaller groups, and each member of each department comes from a distinct background that in itself influences behaviour and interaction.

Suppose we have a group of students who are all similar in age and educational level. Do gender and the societal expectations of roles influence interaction? Of course! There will be differences on multiple levels. Among these students not only do the boys and girls communicate in distinct ways, but there will also be differences among the boys as well as differences among the girls. Even within a group of sisters, common characteristics exist, but they will still have differences, and all these differences contribute to intercultural communication. Our upbringing shapes us. It influences our worldview, what we value, and how we interact with each other. We create culture, and it defines us.

Culture involves beliefs, attitudes, values, and traditions that are shared by a group of people. More than just the clothes we wear, the movies we watch, or the video games we play, all representations of our environment are part of our culture. Culture also involves the psychological aspects and behaviours that are expected of members of our group. For example, if we are raised in a culture where males speak while females are expected to remain silent, the context of the communication interaction governs behaviour. From the choice of words (message), to how we communicate (in person, or by e-mail), to how we acknowledge understanding with a nod or a glance (non-verbal feedback), to the internal and external interference, all aspects of communication are influenced by culture.

Culture consists of the shared beliefs, values, and assumptions of a group of people who learn from one another and teach to others that their behaviours, attitudes, and perspectives are the correct ways to think, act, and feel.

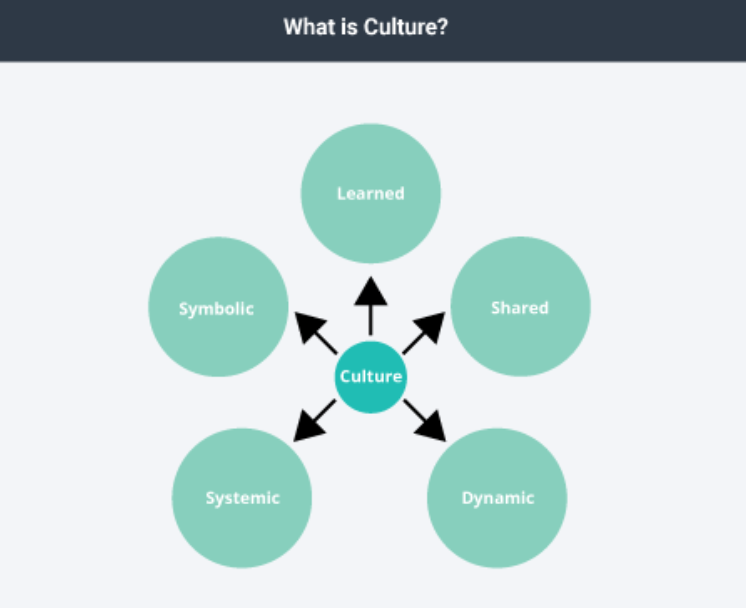

It is helpful to think about culture in the following five ways:

- Culture is learned.

- Culture is shared.

- Culture is dynamic.

- Culture is systemic.

- Culture is symbolic.

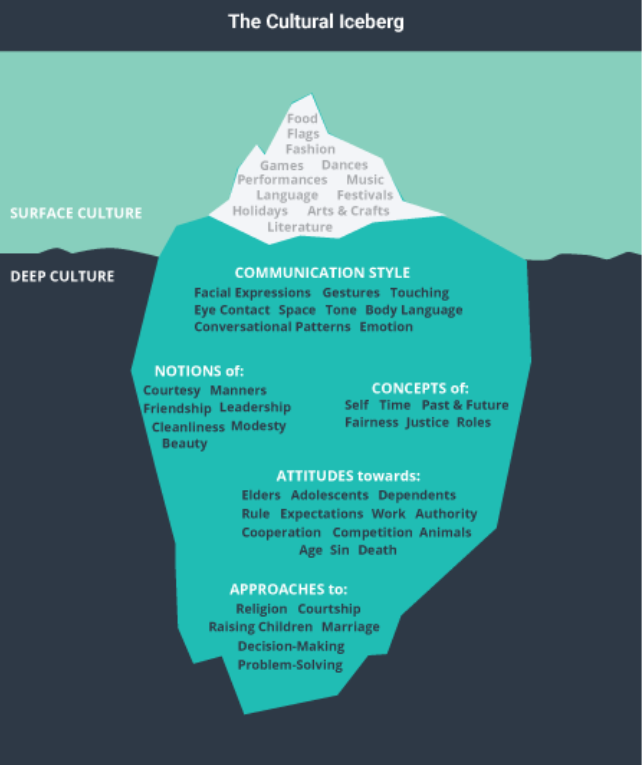

The iceberg, a commonly used metaphor to describe culture, is great for illustrating the tangible and the intangible. When talking about culture, most people focus on the “tip of the iceberg,” which is visible but makes up just 10 percent of the object. The rest of the iceberg, 90 percent of it, is below the waterline. Many business leaders, when addressing intercultural situations, pick up on the things they can see—things on the “tip of the iceberg.” Things like food, clothing, and language difference are easily and immediately obvious, but focusing only on these can mean missing or overlooking deeper cultural aspects such as thought patterns, values, and beliefs that are under the surface. Solutions to any interpersonal miscommunication that results become temporary bandages covering deeply rooted conflicts.

Cultural Membership

How do you become a member of a culture, and how do you know when you are full member? So much of communication relies on shared understanding, that is, shared meanings of words, symbols, gestures, and other communication elements. When we have a shared understanding, communication comes easily, but when we assign different meanings to these elements, we experience communication challenges.

What shared understandings do people from the same culture have? Researchers who study cultures around the world have identified certain characteristics that define a culture. These characteristics are expressed in different ways, but they tend to be present in nearly all cultures:

- rites of initiation

- common history and traditions

- values and principles

- purpose and mission

- symbols, boundaries, and status indicators

Terms to Know

Although they are often used interchangeably, it is important to note the distinctions among multicultural, cross-cultural, and intercultural communication.

Multiculturalism is a rather surface approach to the coexistence and tolerance of different cultures. It takes the perspective of “us and the others” and typically focuses on those tip-of-the-iceberg features of culture, thus highlighting and accepting some differences but maintaining a “safe” distance. If you have a multicultural day at work, for example, it usually will feature some food, dance, dress, or maybe learning about how to say a few words or greetings in a sampling of cultures.

Cross-cultural approaches typically go a bit deeper, the goal being to be more diplomatic or sensitive. They account for some interaction and recognition of difference through trade and cooperation, which builds some limited understanding—such as, for instance, bowing instead of shaking hands, or giving small but meaningful gifts. Even using tools like Hofstede, as you’ll learn about in this chapter, gives us some overarching ideas about helpful things we can learn when we compare those deeper cultural elements across cultures. Sadly, they are not always nuanced comparisons; a common drawback of cross-cultural comparisons is that we can wade into stereotyping and ethnocentric attitudes—judging other cultures by our own cultural standards—if we aren’t mindful.

Lastly, when we look at intercultural approaches, we are well beneath the surface of the iceberg, intentionally making efforts to better understand other cultures as well as ourselves. An intercultural approach is not easy, often messy, but when you get it right, it is usually far more rewarding than the other two approaches. The intercultural approach is difficult and effective for the same reasons; it acknowledges complexity and aims to work through it to a positive, inclusive, and equitable outcome.

Whenever we encounter someone, we notice similarities and differences. While both are important, it is often the differences that contribute to communication troubles. We don’t see similarities and differences only on an individual level. In fact, we also place people into in-groups and out-groups based on the similarities and differences we perceive. Recall what you read about social identity and discrimination in the last chapter—the division of people into in-groups and out-groups is where your social identity can result in prejudice or discrimination if you are not cautious about how you frame this.

We tend to react to someone we perceive as a member of an out-group based on the characteristics we attach to the group rather than the individual (Allen, 2010). In these situations, it is more likely that stereotypes and prejudice will influence our communication. This division of people into opposing groups has been the source of great conflict around the world, as with, for example, the division between Catholics and Protestants in Northern Ireland; between Croats, Serbs, and Bosnian Muslims in the former Yugoslavia; and between males and females during women’s suffrage. Divisions like these can still cause conflict on an individual level. Learning about difference and why it matters will help us be more competent communicators and help to prevent conflict.

Theories of Cross-Cultural Communication

Social psychologist Geert Hofstede (Hofstede, 1982, 2001, 2005) is one of the most well known researchers in cross-cultural communication and management. His website offers useful tools and explanations about a range of cultural dimensions that can be used to compare various dominant national cultures. Hofstede’s theory places cultural dimensions on a continuum that range from high to low and really only make sense when the elements are compared to another culture. Hofstede’s dimensions include the following:

- Power Distance: High-power distance means a culture accepts and expects a great deal of hierarchy; low-power distance means the president and janitor could be on the same level.

- Individualism: High individualism means that a culture tends to put individual needs ahead of group or collective needs.

- Uncertainty Avoidance: High uncertainty avoidance means a culture tends to go to some lengths to be able to predict and control the future. Low uncertainty avoidance means the culture is more relaxed about the future, which sometimes shows in being willing to take risks.

- Masculinity: High masculinity relates to a society valuing traits that were traditionally considered masculine, such as competition, aggressiveness, and achievement. A low masculinity score demonstrates traits that were traditionally considered feminine, such as cooperation, caring, and quality of life.

- Long-term orientation: High long-term orientation means a culture tends to take a long-term, sometimes multigenerational view when making decisions about the present and the future. Low long-term orientation is often demonstrated in cultures that want quick results and that tend to spend instead of save.

- Indulgence: High indulgence means cultures that are OK with people indulging their desires and impulses. Low indulgence or restraint-based cultures value people who control or suppress desires and impulses.

As mentioned previously, these tools can provide wonderful general insight into making sense of understanding differences and similarities across key below-the-surface cross-cultural elements. However, when you are working with people, they may or may not conform to what’s listed in the tools. For example, if you are Canadian but grew up in a tight-knit Amish community, your value system may be far more collective than individualist. Or if you are Aboriginal, your long-term orientation may be far higher than that of mainstream Canada. It’s also important to be mindful that in a Canadian workplace, someone who is non-white or wears clothes or religious symbols based on their ethnicity may be far more “mainstream” under the surface. The only way you know for sure is to communicate interpersonally by using active listening, keeping an open mind, and avoiding jumping to conclusions.

Trompenaars

Fons Trompenaars is another researcher who came up with a different set of cross-cultural measures. A more detailed explanation of his seven dimensions of culture can be found at this website (The Seven Dimensions of Culture, n.d.), but we provide a brief overview below:

- Universalism vs. Particularism: the extent that a culture is more prone to apply rules and laws as a way of ensuring fairness, in contrast to a culture that looks at the specifics of context and looks at who is involved, to ensure fairness. The former puts the task first; the latter puts the relationship first.

- Individualism vs. Communitarianism: the extent that people prioritize individual interests versus the community’s interest.

- Specific vs. Diffuse: the extent that a culture prioritizes a head-down, task-focused approach to doing work, versus an inclusive, overlapping relationship between life and work.

- Neutral vs. Emotional: the extent that a culture works to avoid showing emotion versus a culture that values a display or expression of emotions.

- Achievement vs. Ascription: the degree to which a culture values earned achievement in what you do versus ascribed qualities related to who you are based on elements like title, lineage, or position.

- Sequential Time vs. Synchronous Time: the degree to which a culture prefers doing things one at time in an orderly fashion versus preferring a more flexible approach to time with the ability to do many things at once.

- Internal Direction vs. Outer Direction: the degree to which members of a culture believe they have control over themselves and their environment versus being more conscious of how they need to conform to the external environment.

Like Hofstede’s work, Trompenaars’s dimensions help us understand some of those beneath-the-surface-of-the-iceberg elements of culture. It’s equally important to understand our own cultures as it is to look at others, always being mindful that our cultures, as well as others, are made up of individuals.

Ting-Toomey

Stella Ting-Toomey’s face negotiation theory builds on some of the cross-cultural concepts you’ve already learned, such as, for example, individual versus collective cultures. When discussing face negotiation theory, face means your identity, your image, how you look or come off to yourself and others (communicationtheory.org, n.d.). The theory says that this concern for “face” is something that is common across every culture, but various cultures—especially Eastern versus Western cultures—approach this concern in different ways. Individualist cultures, for example tend to be more concerned with preserving their own face, while collective cultures tend to focus more on preserving others’ faces. Loss of face leads to feelings of embarrassment or identity erosion, whereas gaining or maintaining face can mean improved status, relations, and general positivity. Actions to preserve or reduce face is called facework. Power distance is another concept you’ve already learned that is important to this this theory. Most collective cultures tend to have more hierarchy or a higher power distance when compared to individualist cultures. This means that maintaining the face of others at a higher level than yours is an important part of life. This is contrasted with individualist cultures, where society expects you to express yourself, make your opinion known, and look out for number one. This distinction becomes really important in interpersonal communication between people whose cultural backgrounds have different approaches to facework; it usually leads to conflict. Based on this dynamic, the following conflict styles typically occur:

- Domination: dominating or controlling the conflict (individualist approach)

- Avoiding: dodging the conflict altogether (collectivist approach)

- Obliging: yielding to the other person (collectivist approach)

- Compromising: a give-and-take negotiated approach to solving the conflict (individualist approach)

- Integrating: a collaborative negotiated approach to solving the conflict (individualist approach)

Another important facet of this theory involves high-context versus low-context cultures. High-context cultures are replete with implied meanings beyond the words on the surface and even body language that may not be obvious to people unfamiliar with the context. Low-context cultures are typically more direct and tend to use words to attempt to convey precise meaning. For example, an agreement in a high-context culture might be verbal because the parties know each other’s families, histories, and social position. This knowledge is sufficient for the agreement to be enforced. No one actually has to say, “I know where you live. If you don’t hold up your end of the bargain, …” because the shared understanding is implied and highly contextual. A low-context culture usually requires highly detailed, written agreements that are signed by both parties, sometimes mediated through specialists like lawyers, as a way to enforce the agreement. This is low context because the written agreement spells out all the details so that not much is left to the imagination or “context.”

Verbal and Non-Verbal Differences

Cultures have different ways of verbally expressing themselves. For example, consider the people of the United Kingdom. Though English is spoken throughout the UK, the accents can be vastly different from one city or county to the next. If you were in conversation with people from each of the four countries that make up the UK—England, Northern Ireland, Scotland, and Wales, you would find that each person pronounces words differently. Even though they all speak English, each has their own accent, slang terms, speaking volume, metaphors, and other differences. You would even find this within the countries themselves. A person who grew up in the south of England has a different accent than someone from the north, for example. This can mean that it is challenging for people to understand one another clearly, even when they are from the same country!

While we may not have such distinctive differences in verbal delivery within Canada, we do have two official languages, as well as many other languages in use within our borders. This inevitably means that you’ll communicate with people who have different accents than you do, or those who use words and phrases that you don’t recognize. For example, if you’re Canadian, you’re probably familiar with slang terms like toque (a knitted hat), double-double (as in, a coffee with two creams and two sugars—preferably from Tim Hortons), parkade (parking garage), and toonie (a two-dollar coin), but your friends from other countries might respond with quizzical looks when you use these words in conversation!

When communicating with someone who has a different native language or accent than you do, avoid using slang terms and be conscious about speaking clearly. Slow down, and choose your words carefully. Ask questions to clarify anything that you don’t understand, and close the conversation by checking that everything is clear to the other person.

Cultures also have different non-verbal ways of delivering and interpreting information. For example, some cultures may treat personal space differently than do people in North America, where we generally tend to stay as far away from one another as possible. For example, if you get on an empty bus or subway car and the next person who comes on sits in the seat right next to you, you might feel discomfort, suspicion, or even fear. In a different part of the world this behaviour might be considered perfectly normal. Consequently, when people from cultures with different approaches to space spend time in North America, they can feel puzzled at why people aim for so much distance. They may tend to stand closer to other people or feel perfectly comfortable in crowds, for example.

This tendency can also come across in the level of acceptable physical contact. For example, kissing someone on the cheek as a greeting is typical in France and Spain—and could even be a method of greeting in a job interview. In North America, however, we typically use a handshake during a formal occasion and apologize if we accidentally touch a stranger’s shoulder as we brush past. In contrast, Japanese culture uses a non-contact form of greeting—the bow—to demonstrate respect and honour.

Meaning and Mistranslation

Culturally influenced differences in language and meaning can lead to some interesting encounters, ranging from awkward to informative to disastrous. In terms of awkwardness, you have likely heard stories of companies that failed to exhibit communication competence in their naming and/or advertising of products in another language. For example, in Taiwan, Pepsi used the slogan “Come Alive With Pepsi,” only to find out later that, when translated, it meant, “Pepsi brings your ancestors back from the dead” (Kwintessential, 2012). Similarly, American Motors introduced a new car called the Matador to the Puerto Rican market, only to learn that Matador means “killer,” which wasn’t very comforting to potential buyers.

At a more informative level, the words we use to give positive reinforcement are culturally relative. In Canada and the United Kingdom, for example, parents commonly reinforce their child’s behaviour by saying, “Good girl” or “Good boy.” There isn’t an equivalent for such a phrase in other European languages, so the usage in only these two countries has been traced back to the puritan influence on beliefs about good and bad behaviour (Wierzbicka, 2004).

One of the most publicized and deadliest cross-cultural business mistakes occurred in India in 1984. Union Carbide, an American company, controlled a plant used to make pesticides. The company underestimated the amount of cross-cultural training that would be needed to allow the local workers, many of whom were not familiar with the technology or language/jargon used in the instructions for plant operations, to do their jobs. This lack of competent communication led to a gas leak that killed more than 2,000 people and, over time, led to more than 500,000 injuries (Varma, 2012).

Language and Culture

Through living and working in five different countries, one of the authors notes that when you learn a language, you learn a culture. In fact, a language can tell you a lot about a culture if you look closely. Here’s one example:

A native English speaker landed in South Korea and tried to learn the basics of saying hello in the Korean language. Well, it turned out that it wasn’t as simple as saying hello! It depended on whom you are saying hello to. The Korean language has many levels and honorifics that dictate not only what you say but also how you say it and to whom. So, even a mere hello is not straightforward; the words change. For example, if you are saying hello to someone younger or in a lower position, you will use (anyeong); but for a peer at the same level, you will use a different term (anyeoung ha seyo); and a different one still for an elder, superior, or dignitary (anyeong ha shim nikka). As a result, the English speaker learned that in Korea people often ask personal questions upon meeting—questions such as, How old are you? Are you married? What do you do for a living? At first, she thought people were very nosy. Then she realized that it was not so much curiosity driving the questions but, rather, the need to understand how to speak to you in the appropriate way.

In Hofstede’s terms, this adherence to hierarchy or accepted “levels” in society speak to the notion of moving from her home country (Canada) with a comparatively low power distance to a country with a higher power distance. These contrasting norms show that what’s considered normal in a culture is also typically reflected to some degree in the language.

What are the implications of this for interpersonal communication? What are the implications of this for body language (bowing) in the South Korean context? What are the ways to be respectful or formal in your verbal and non-verbal language?

Comparing and Contrasting

How can you prepare to work with people from cultures different than your own? Start by doing your homework. Let’s assume that you have a group of Japanese colleagues visiting your office next week. How could you prepare for their visit? If you’re not already familiar with the history and culture of Japan, this is a good time to do some reading or a little bit of research online. If you can find a few English-language publications from Japan (such as newspapers and magazines), you may wish to read through them to become familiar with current events and gain some insight into the written communication style used.

Preparing this way will help you to avoid mentioning sensitive topics and to show correct etiquette to your guests. For example, Japanese culture values modesty, politeness, and punctuality, so with this information, you can make sure you are early for appointments and do not monopolize conversations by talking about yourself and your achievements. You should also find out what faux pas to avoid. For example, in company of Japanese people, it is customary to pour others’ drinks (another person at the table will pour yours). Also, make sure you do not put your chopsticks vertically in a bowl of rice, as this is considered rude. If you have not used chopsticks before and you expect to eat Japanese food with your colleagues, it would be a nice gesture to make an effort to learn. Similarly, learning a few words of the language (e.g., hello, nice to meet you, thank you, and goodbye) will show your guests that you are interested in their culture and are willing to make the effort to communicate.

If you have a colleague who has travelled to Japan or has spent time in the company of Japanese colleagues before, ask them about their experience so that you can prepare. What mistakes should you avoid? How should you address and greet your colleagues? Knowing the answers to these questions will make you feel more confident when the time comes. But most of all, remember that a little goes a long way. Your guests will appreciate your efforts to make them feel welcome and comfortable. People are, for the most part, kind and understanding, so if you make some mistakes along the way, don’t worry too much. Most people are keen to share their culture with others, so your guests will be happy to explain various practices to you.

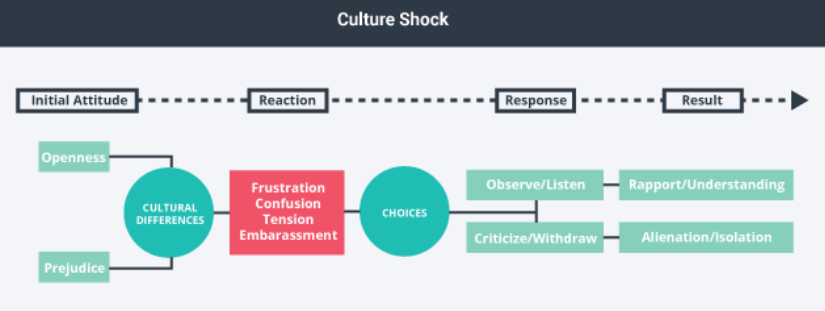

You might find that, in your line of work, you are expected to travel internationally. When you visit a country that is different from your own, you might experience culture shock. Defined as “the feeling of disorientation experienced by someone when they are suddenly subjected to an unfamiliar culture, way of life, or set of attitudes” (OxfordDictionaries.com, 2015), it can disorient us and make us feel uncertain when we are in an unfamiliar cultural climate. Have you ever visited a new country and felt overwhelmed by the volume of sensory information coming at you? From new sights and smells to a new language and unfamiliarity with the location, the onset of culture shock is not entirely surprising. To mitigate this, it helps to read as much as you can about the new culture before your visit. Learn some of the language and customs, watch media programs from that culture to familiarize yourself, and do what you can to prepare. But remember not to hold the information you gather too closely. In doing so, you risk going in with stereotypes. As shown in the figure above, going in with an open attitude and choosing to respond to difficulties with active listening and non-judgmental observation typically leads to building rapport, understanding, and positive outcomes over time.

Culture Shock

Experiencing culture shock does not require you to leave Canada. Moving from a rural to an urban centre (or vice versa), from an English-speaking to a French-speaking area, or moving to or from an ethnic enclave can challenge your notion of what it is to be a Canadian.

In one example, one of the authors participated in a language-based homestay in rural Quebec the summer before her first year of university. Prior to this, she had attended an urban high school in Toronto where the majority of her classmates were non-white and into urban music. When she went to take the train and saw that all the other kids were white, listening to alternative music, and playing hackey sack, she began to worry.

When she met her house mother upon arrival, the house mom looked displeased. Out of four students to stay in her home, two were non-white. The students discovered quickly that the house dad was a hunter, evident by the glass cabinet full of shotguns and the mounted moose heads on the wall. To add to all these changes, the students were forbidden to speak English as a way to help make the most of the French language immersion program. About two weeks into the program, the student from Toronto, a black girl, overheard the house mom talking with her roommate, a white girl from London, Ontario. She said, “You know, I was really concerned when I saw that we had a black and an Asian student, because we never had any people like that in our house before, so I didn’t know what to expect. But now, you know especially with your roommate from Toronto, I can see that they’re just like normal people!”

The urban to rural transition was stark, the language immersion was a challenge, and the culture of the other students as well as that of the host family was also a big change. With so many changes happening, one outcome that is consistent with what we know about one aspect of culture shock, is that most of the students on this immersion program reported sleeping way longer hours than usual. It’s but one way for your mind and body to cope with the rigours of culture shock!

Despite all the challenges, however, the benefit for the author was a 30 percent improvement in French language skills—skills that later came in handy during bilingual jobs, trips to France, and the ability to communicate with the global French-speaking community.

A Changing Worldview

One helpful way to develop your intercultural communication competence is to develop sensitivity to intercultural communication issues and best practices. From everything we have learned so far, it may feel complex and overwhelming. The Intercultural Development Continuum is a theory created by Mitchell Hammer (2012) that helps demystify the process of moving from monocultural approaches to intercultural approaches. There are five steps in this transition, and we will give a brief overview of each one below.

See if you can deduce the main points of the overview before expanding the selection.

The first two steps out of five reflect monocultural mindsets, which are ethnocentric. As you recall, ethnocentrism means evaluating other cultures according to preconceptions originating in the standards and customs of one’s own culture (OxfordDictionaries.com, 2015).

People who belong to dominant cultural groups in a given society or people who have had very little exposure to other cultures may be more likely to have a worldview that’s more monocultural according to Hammer (2009). But how does this cause problems in interpersonal communication? For one, being blind to the cultural differences of the person you want to communicate with (denial) increases the likelihood that you will encode a message that they won’t decode the way you anticipate, or vice versa.

For example, let’s say culture A considers the head a special and sacred part of the body that others should never touch, certainly not strangers or mere acquaintances. But let’s say in your culture people sometimes pat each other on the head as a sign of respect and caring. So you pat your culture A colleague on the head, and this act sets off a huge conflict.

It would take a great deal of careful communication to sort out such a misunderstanding, but if each party keeps judging the other by their own cultural standards, it’s likely that additional misunderstanding, conflict, and poor communication will transpire.

Using this example, polarization can come into play because now there’s a basis of experience for selective perception of the other culture. Culture A might say that your culture is disrespectful, lacks proper morals, and values, and it might support these claims with anecdotal evidence of people from your culture patting one another on the sacred head!

Meanwhile, your culture will say that culture A is bad-tempered, unintelligent, and angry by nature and that there would be no point in even trying to respect or explain things them.

It’s a simple example, but over time and history, situations like this have mounted and thus led to violence, even war and genocide.

According to Hammer (2009) the majority of people who have taken the IDI inventory, a 50-question questionnaire to determine where they are on the monocultural–intercultural continuum, fall in the category of minimization, which is neither monocultural nor intercultural. It’s the middle-of-the-road category that on one hand recognizes cultural difference but on the other hand simultaneously downplays it. While not as extreme as the first two situations, interpersonal communication with someone of a different culture can also be difficult here because of the same encoding/decoding issues that can lead to inaccurate perceptions. On the positive side, the recognition of cultural differences provides a foundation on which to build and a point from which to move toward acceptance, which is an intercultural mindset.

There are fewer people in the acceptance category than there are in the minimization category, and only a small percentage of people fall into the adaptation category. This means most of us have our work cut out for us if we recognize the value—considering our increasingly global societies and economies—of developing an intercultural mindset as a way to improve our interpersonal communication skill.

In this chapter on cross-cultural communication you learned about culture and how it can complicate interpersonal communication. Culture is learned, shared, dynamic, systemic, and symbolic. You uncovered the distinction between multicultural, cross-cultural, and intercultural approaches and discovered several new terms such as diplomatic, ethnocentric, and in-/out-groups.

From there you went on to examine the work three different cross-cultural theorists including Hofstede, Trompenaars, and Ting-Toomey. After reviewing verbal and non-verbal differences, you went on to compare and contrast by doing your homework on what it might be like to communicate interpersonally with members of another culture and taking a deeper look into culture shock.

Finally, you learned about the stages on the intercultural development continuum that move from an ethnocentric, monocultural worldview to a more intercultural worldview.

The ability to communicate well between cultures is an increasingly sought-after skill that takes time, practice, reflection, and a great deal of work and patience. This chapter has introduced you to several concepts and tools that can put you on the path to further developing your interpersonal skills to give you an edge and better insight in cross-cultural situations.

Key Takeaways and Check In

Learning highlights

- The iceberg model helps to show us that a few easily visible elements of culture are above the surface but that below the surface lie the invisible and numerous elements that make up culture.

- Ethnocentrism is an important word to know; it indicates a mindset that your own culture is superior while others are inferior.

- Whether a culture values individualism or the collective community is a recurring dimension in many cross-cultural communication theories, including those developed by Hofstede, Trompenaars, and Ting-Toomey.

- Language can tell you a great deal about a culture.

- The intercultural development model helps demystify the change from monocultural mindsets to intercultural mindsets.

Further Reading, Links, and Attribution

Further reading and links.

- A student’s reflection on experiencing culture shock .

- Stella Ting-Toomey discusses face negotiation theory in this YouTube video.

Allen, B. (2010). Difference matters: Communicating social identity. Waveland Press.

culture shock. (n.d.). In Oxford Dictionaries. Retrieved from http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/culture-shock

ethnocentric. (n.d.). In Oxford Dictionaries. Retrieved from http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/ethnocentric .

Face-Negotiation Theory. (n.d.). Communication Theory. Retrieved from http://communicationtheory.org/face-negotiation-theory/ .

Hammer, M.R. (2009). The Intercultural Development Inventory. In M. A. Moodian (Ed.). Contemporary Leadership and Intercultural Competence . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hofstede, G. (1982). Culture’s consequences (2nd ed.). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hofstede, G. (2005). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind (Revised and expanded 2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Lindner, M. (2013). Edward T. Hall’s Cultural Iceberg. Prezi presentation retrieved from https://prezi.com/y4biykjasxhw/edward-t-halls-cultural-iceberg/?utm_source=prezi-view&utm_medium=ending-bar&utm_content=Title-link&utm_campaign=ending-bar-tryout .

Results of Poor Cross Cultural Awareness . (n.d.) Kwintessential Ltd. Retrieved from http://www.kwintessential.co.uk/cultural-services/articles/results-of-poor-cross-cultural-awareness.html .

The Seven Dimensions of Culture: Understanding and managing cultural differences. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.mindtools.com/pages/article/seven-dimensions.htm .

Varma, S. (2010, June 20). Arbitrary? 92% of All Injuries Termed Minor . The Times of India. Retrieved from http://articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/2010-06-20/india/28309628_1_injuries-gases-cases .

Wierzbicka, A. (2004). The English expressions good boy and good girl and cultural models of child rearing. Culture & Psychology, 10 (3), 251‒278.

Attribution Statement (Cross-Cultural Communication)

This chapter is a remix containing content from a variety of sources published under a variety of open licenses, including the following:

Chapter Content

- Original content contributed by the Olds College OER Development Team, of Olds College to Professional Communications Open Curriculum under a CC-BY 4.0 license

- Content created by Anonymous for Understanding Culture; in Cultural Intelligence for Leaders, previously shared at http://2012books.lardbucket.org/books/cultural-intelligence-for-leaders/s04-understanding-culture.html under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 license

- Derivative work of content created by Anonymous for Intercultural and International Group Communication; in An Introduction to Group Communication, previously shared at http://2012books.lardbucket.org/books/an-introduction-to-group-communication/s07-intercultural-and-internationa.html under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 license

- Content created by Anonymous for Language, Society, and Culture; in A Primer on Communication Studies, previously shared at http://2012books.lardbucket.org/books/a-primer-on-communication-studies/s03-04-language-society-and-culture.html under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 license

Check Your Understandings

- Original assessment items contributed by the Olds College OER Development Team, of Olds College to Professional Communications Open Curriculum under a CC-BY 4.0 license

- Assessment items created by Boundless, for Boundless Managing Diversity Quiz, previously shared at https://www.boundless.com/quizzes/managing-diversity-quiz-2584/ under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license

- Assessment items adapted from The Saylor Foundation for the saylor.org course Comm 311: Intercultural Communication, previously shared at http://saylordotorg.github.io/LegacyExams/COMM/COMM311/COMM311-FinalExam-Answers.html under a CC BY 3.0 US license

Cross-Cultural Communication Copyright © by Olds College. All Rights Reserved.

Share This Book

Cross-Cultural Communication

Navigating the Ups and Downs of Global Teamwork

In today's globalized business environment, effectively communicating across cultures is not just an asset but a necessity. Multicultural teams are now commonplace, bringing together diverse perspectives that can lead to innovative solutions and growth. However, this amalgamation of different cultures also presents unique challenges, from misunderstandings rooted in cultural nuances to differing approaches to hierarchy and decision-making.

Effective cross-cultural communication fosters an environment where every team member feels valued and understood. The ideal dynamic involves a seamless exchange of ideas, where diversity is leveraged as a strength rather a hurdle, enabling teams to collaborate efficiently and harmoniously toward their common goals.

What is cross-cultural communication?

Cross-cultural communication is the process of recognizing both differences and similarities among cultural groups to effectively engage within a given context. In other words, cross-cultural communication refers to how people from different cultural backgrounds adjust to improve communication. (1)

Common Causes of Cross-Cultural Communication Failures

Navigating the complex landscape of cross-cultural communication in the workplace reveals several common pitfalls that can lead to misunderstandings and inefficiencies. These factors can significantly hinder a team’s potential, making it crucial to address them with thoughtful strategies and an open mind. The following are a few of the most pervasive of these barriers.

- Linguistic Prejudice: One significant barrier is linguistic prejudice—or prejudice against a person based on how they talk (2). Biases towards certain accents, dialects, or the fluency of a second language can inadvertently undermine the confidence and contributions of team members.

- Cultural Insensitivity: Cultural misunderstandings or insensitivity can fracture team cohesion. For instance, what is considered a polite gesture in one culture might be considered offensive in another, leading to unintended disrespect or conflict.

- Time Differences: Time differences pose a practical challenge, complicating meeting schedules and deadlines, and can strain communication if not managed with flexibility and understanding.

- Judgement: Moreover, the judgment of the "right" and "wrong" way to communicate or execute tasks, rooted in one's cultural background, can create friction. This judgment often stems from a lack of awareness that different cultures may have varying approaches to problem-solving, decision-making, and expressing ideas, leading to a narrow view of efficiency and effectiveness.

What Doesn’t Work

In the attempt to create more inclusive and harmonious work environments, certain approaches have proven to be less effective and in some cases, counterproductive.

“Winging It”

Adopting a hands-off approach to cross-cultural communication in teams often falls short because it overlooks the necessity of deliberate efforts to recognize and respect cultural differences. Such a strategy fails to foster an inclusive environment, as it neglects the importance of educating team members about diverse perspectives and encouraging open dialogue about cultural backgrounds and their impact on work and communication styles. Without intentional communication, teams risk misunderstandings and conflicts due to unrecognized cultural nuances. For example, behaviors viewed as assertive in one culture may be seen as aggressive in another, leading to unnecessary tensions. Simply put, effective cross-cultural teamwork requires more than good intentions; it demands active engagement and education to appreciate the value of diversity and navigate the complexities of cultural differences.

Antiprejudice Campaigns

Efforts to combat prejudice through campaigns that pressure people to alter their thoughts or behavior often backfire, leading to an increase rather than a decrease in prejudicial attitudes (4) . Studies have shown that these well-intentioned initiatives might amplify biases since efforts to root out unconscious biases could make individuals overly sensitive to potential offenses, creating a workplace atmosphere charged with tension and suspicion, and sometimes even unfounded allegations. Additionally, such initiatives have been linked to adverse mental health outcomes, such as heightened levels of stress and depression among staff.

In the middle of these two extremes lies a more balanced and successful approach, one that not only promotes cooperative efforts and seeks beneficial results for everyone involved but also helps in building a foundation where diverse teams can thrive.

So, What Does Work?

Creating a thriving workplace that excels in cross-cultural communication and teamwork requires a strategic approach that focuses on what has been shown to work. Implementing practices that foster understanding, respect, and collaboration among diverse team members can significantly enhance productivity and workplace harmony. Below are key strategies that have been proven effective in navigating the complexities of global teamwork:

- Expectation of Positive Behaviors: People often rise to meet the expectations set for them. Leaders can cultivate an environment where such behaviors become the norm by clearly communicating a standard of positive and respectful behavior within the team. This principle hinges on the belief that when team members are aware of the standards expected of them, they are more inclined to adjust their actions accordingly.

- Training in Negotiation and Conflict: Providing team members with training in negotiation and conflict resolution equips them with the skills to handle disagreements constructively. This training helps in managing emotions, engaging in positive dialogue, and finding mutually satisfying solutions to conflicts.

- Respecting Differences: It is crucial to acknowledge and respect the differences in how tasks are approached and completed across cultures. Understanding that there is more than one way to achieve a goal fosters an environment of creativity and innovation .

- Recognizing Customs for Religious and National Holidays: Being mindful of and accommodating religious and national holidays in the planning of deadlines and meetings demonstrates respect for the cultural and personal lives of team members, enhancing feelings of inclusion and belonging.

- Establishing Communication Standards: Developing clear standards for communication that take into account language differences and communication preferences helps in minimizing misunderstandings and ensures that all team members feel heard and understood.

- Setting Clear Work Policies: Transparent work policies sensitive to cultural differences provide a framework for fairness and equality. This includes policies on work hours, communication protocols, and conflict resolution procedures.

- Collaboration and Feedback: Encouraging open collaboration and regular feedback supports a dynamic learning environment where team members can grow and improve together. This also helps identify and address any cultural misunderstandings early on.

- Team Building and Camaraderie: Investing in team-building activities that allow team members to share their cultures and customs can significantly enhance camaraderie and understanding within the team. Getting to know each other personally bridges cultural gaps and builds a strong foundation for teamwork.

The journey towards effective cross-cultural collaboration is ongoing and demands continuous effort and adaptation. However, the rewards of a harmonious, inclusive, and productive workplace are well worth the investment. By embracing these principles, teams can overcome the challenges of working across cultures and thrive in the rich opportunities that such diversity brings.

- How to Improve Cross-Cultural Communication in the Workplace , 2019, Northeastern University Graduate Programs

- Advancing Language for Racial Equity and Inclusion , Berkeley Haas Center for Equity, Gender & Leadership

- Managing Cross Cultural Remote Teams | Ricardo Fernandez | TEDxIESEBarcelona

- Are You Ready for Gen Z in the Workplace? 2019, California Management Review

- People Skills for a Multicultural Workplace , 2018, CHRON

- Managing Cross Cultural Remote Teams: Considerations Every Team Should Have, We Work Remotely

Dive Deeper

Take a deep-dive into this topic and gain expert, working knowledge by joining us for the program that inspired it!

Equity Fluent Leadership Program

Learn why diversity & inclusion matter, how to drive impactful change, and research-driven methods to expand equity within your company.

Communications Excellence Program

A communication skills training to develop your confidence and presentation abilities. Learn how to create a memorable pitch.

The Berkeley Executive Leadership Program

Advance your leadership qualities, build skills to strategically address business challenges head-on, and apply strategic decision-making.

Related Insights

How to Have Difficult Conversations

Mastering the art of difficult conversations has become an indispensable skill for leaders and employees alike. Whether it's navigating conflicts..

Enhancing Intergenerational Communication

Bridging geographical divides is a familiar hurdle for global and dispersed teams. However, an equally pressing yet often less addressed challenge..

Effective Communication in the Workplace

Language is powerful. It can shape workplace dynamics, particularly during difficult conversations that make or break team cohesion. Words can build..

How To Improve Cross-Cultural Communication in the Workplace

Industry Advice Communications & Digital Media

It’s no secret that effective communication is central to the success of any organization, regardless of industry. But in order to truly understand what it takes to communicate effectively, you must first understand the different cultural factors that influence the way people interact with one another.

Our world is more interconnected than ever before, a fact that has given rise to many changes in the ways that businesses and organizations operate. Workplaces are more diverse, remote teams are scattered across the country or around the world, and businesses that once sold products to a single demographic might now sell to a global market. All of these factors have converged to make cross-cultural communication a vital part of organizational success.

Here’s a look at why cross-cultural communication is important in the workplace, and the steps you can take to overcome cultural barriers and improve communication within your organization.

What is cross-cultural communication?

Cross-cultural communication is the process of recognizing both differences and similarities among cultural groups in order to effectively engage within a given context. In other words, cross-cultural communication refers to the ways in which people from different cultural backgrounds adjust to improve communication with one another.

In today’s rapidly changing professional world, it’s critical to gain an understanding of how cultural elements influence communication between individuals and groups in the workplace. Developing strong cross-cultural communication skills is the first step in creating a successful work environment that brings out the best in all of an organization’s team members.

Why is cross-cultural communication important?

To be successful in any industry, organizations need to understand the communication patterns of employees, customers, investors, and other audiences. Awareness and willingness to adjust allow for the exchange of information regardless of cultural values, norms, and behaviors that may vary between audiences.

Given the different backgrounds that each audience comes from, it is critical to understand how culture influences communication, and how this can impact organizational processes.

“Effective cross-cultural communication is essential to preventing and resolving conflict, building networks, and creating a satisfactory work environment for everyone involved,” says Patty Goodman, PhD, associate teaching professor in Northeastern’s Master of Science in Corporate and Organizational Communications program.

Additionally, the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM) reports that culture has a significant impact on productivity. As such, it is important to be cognizant of the fact that “employees from different backgrounds are motivated by different incentives and react differently to various management and communication styles.”

How to improve cross-cultural communication

Here are four tips to help you improve cross-cultural communication in your organization.

1. Embrace agility.

The inability or unwillingness to adapt to change is a common barrier to cross-cultural communication. Often, people are reluctant to accept new things due to an unconscious fear that doing so will change their culture or belief system in some way, Goodman explains. If these assumptions are not questioned, actions can be detrimental to personal and organizational growth. By becoming aware of unconscious barriers or subconscious biases, people can become more open to adapting.

“When an organization becomes too set in its ways, it can halt improvements because they are not open to trying different ways of doing things,” Goodman says.

Instead, organizations need to be focused on continuous improvement, which requires a certain degree of flexibility and willingness to try different ways of doing things. Unfortunately, there is no one-size-fits-all solution to this problem. Rather, the best way to address the issue often involves getting started on an individual level.

To begin, consider stepping out of your comfort zone and trying new things in the workplace. In terms of cross-cultural communication, one of the best ways to embrace this idea is to try new methods of doing things in ways that can help you better understand the perspectives of others.

2. Be open-minded.

Similarly, closed-mindedness is another barrier to cross-cultural communication that can hinder the success of an organization.

“People get caught in the trap of thinking that there is one right way to do things and everything else is wrong,” Goodman points out.

On a personal level, becoming more open-minded can be as simple as learning more about an idea that you wouldn’t have considered otherwise. Being exposed to new viewpoints and making the effort to understand them can have an impact on how you make decisions moving forward.

On the other hand, when you’re in a situation where you must work with a closed-minded individual, Goodman suggests you ask questions and look for opportunities to offer a range of thoughts for your audience by providing reliable and valid pieces of data. Leveraging accurate data can be a powerful tool when convincing someone to consider other ideas. By discussing options and listening, you can build trust.

However, presenting this information in an effective way can be a challenge. If people feel overwhelmed by the information or do not trust its validity, it can have the opposite effect. Be sure to carefully identify and present the information to successfully encourage others to approach new ideas with an open mind.

3. Facilitate meaningful conversation.

A lack of communication in an organization can exacerbate cultural differences between individuals. In an environment that does not allow for open communication, people tend not to speak up or share comments and feedback with one another.

So how might members of an organization facilitate open conversation and freely interact with each other? Although the organizational culture is unlikely to change overnight, making the effort to spark conversations on the individual level can be a step in the right direction.

“One of the best ways to get started is to connect with someone who might have a different perspective from your own,” Goodman remarks. “Start a conversation with someone in another department and ask questions, and try to gain a better understanding of their point of view by actively listening.”

Not only will this allow you to gain an understanding and appreciation for another person’s perspective, but it will also help to build strong relationships in the workplace. Goodman recommends “being curious, asking questions, and being open to different points of view.”

Encouraging meaningful interactions also has a significant impact on the overall environment by creating a comfortable space where team members can openly share their thoughts and ideas.

4. Become aware.

Another important step to improving cross-cultural communication in the workplace is to become more culturally and self-aware .

On a personal level, you should make an effort to acknowledge your own implicit biases and assumptions that affect the way you interact with others. Although this may be easier said than done, you can start by making a conscious attempt to empathize with your audience and gain a better understanding of their point of view.

At the organizational level, Goodman recommends starting with an audit of internal communications. Throughout this process, you should be asking how your mission and company values are defined, whether or not they are inclusive, and whether the team’s various cultures have been taken into account. Performing this analysis will give you a good idea of the state of your corporate culture, including areas in your organizational communication strategy that you can improve to better serve your team members and achieve your goals.

Improving workplace communication

Cross-cultural communication is just one (albeit important) aspect of an organization’s overall communication strategy, and improving in this area can be a great first step in maximizing employee and business performance overall.

In addition to the tips listed above, learning the foundations of corporate communications can provide you with the skills needed to understand all of the factors that influence communication in the workplace. Earning a master’s degree in corporate communications can help you do just that.

Northeastern’s Corporate and Organizational Communication program, in particular, is designed to instill students with the theoretical foundations of communication theory, as well as the practical skills necessary to excel professionally.

“Formal education challenges you to think critically and creates an environment where you can practice your communication skills in order to be effective in the real world,” Goodman says.

By enrolling in such a program, you are met with countless opportunities to interact with experts in the field and practice experiential learning.

Additionally, Northeastern’s program offers several concentrations tailored to students’ career goals, including a concentration in cross-cultural communication. This particular track offers practical tools to successfully navigate cultural fields of interest and gain skills to develop a cultural audit. Learn more about Northeastern’s Master of Science in Corporate and Organizational Communication or our Graduate Certificate in Cross-Cultural Communication to see how you can improve your skills and gain a career advantage.

Editor’s Note: This post was originally published in November 2019. It has since been updated for relevance and accuracy.

Subscribe below to receive future content from the Graduate Programs Blog.

About shayna joubert, related articles.

12 Communication Skills That Will Advance Your Career

How to Develop an Internal Communication Strategy

What Is Corporate Communications? Careers and Skills

Did you know.

Advanced degree holders earn a salary an average 25% higher than bachelor's degree holders. (Economic Policy Institute, 2021)

Northeastern University Graduate Programs

Explore our 200+ industry-aligned graduate degree and certificate programs.

Most Popular:

Tips for taking online classes: 8 strategies for success, public health careers: what can you do with an mph, 7 international business careers that are in high demand, edd vs. phd in education: what’s the difference, 7 must-have skills for data analysts, in-demand biotechnology careers shaping our future, the benefits of online learning: 8 advantages of online degrees, how to write a statement of purpose for graduate school, the best of our graduate blog—right to your inbox.

Stay up to date on our latest posts and university events. Plus receive relevant career tips and grad school advice.

By providing us with your email, you agree to the terms of our Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.

Keep Reading:

Top Higher Education Conferences To Attend in 2024

Grad School or Work? How To Balance Both

Is a Master’s in Computer Science Worth the Investment?

Should I Go to Grad School: 4 Questions To Consider

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 23 March 2022

Communication competencies, culture and SDGs: effective processes to cross-cultural communication

- Stella Aririguzoh 1

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 9 , Article number: 96 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

39k Accesses

36 Citations

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Business and management

- Cultural and media studies

Globalization has made it necessary for people from different cultures and nations to interact and work together. Effective cross-cultural communication seeks to change how messages are packaged and sent to people from diverse cultural backgrounds. Cross-cultural communication competencies make it crucial to appreciate and respect noticeable cultural differences between senders and receivers of information, especially in line with the United Nations’ (UN) recognition of culture as an agent of sustainable development. Miscommunication and misunderstanding can result from poorly encrypted messages that the receiver may not correctly interpret. A culture-literate communicator can reduce miscommunication arising from a low appreciation of cultural differences so that a clement communication environment is created and sustained. This paper looks at the United Nations’ recognition of culture and how cultural differences shape interpersonal communication. It then proposes strategies to enhance cross-cultural communication at every communication step. It advocates that for the senders and receivers of messages to improve communication efficiency, they must be culture and media literates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Assessment of the impacts of artificial intelligence (AI) on intercultural communication among postgraduate students in a multicultural university environment

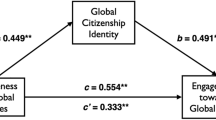

Global citizenship identity mediates the relationship of knowledge, cognitive, and socio-emotional skills with engagement towards global issues

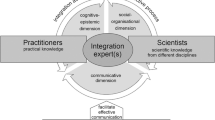

Communication tools and their support for integration in transdisciplinary research projects

Public interest.

The United Nations has recognized culture as a causal agent of sustainability and integrated it into the SDG goals. Culture reinforces the economic, social, and communal fabrics that regulate social cohesion. Communication helps to maintain social order. The message’s sender and the receiver’s culture significantly influence how they communicate and relate with other people outside their tribal communities. Globalization has compelled people from widely divergent cultural backgrounds to work together.

People unconsciously carry their cultural peculiarities and biases into their communication processes. Naturally, there have been miscommunications and misunderstandings because people judge others based on their cultural values. Our cultures influence our behaviour and expectations from other people.

Irrespective of our ethnicities, people want to communicate, understand, appreciate, and be respected by others. Culture literate communicators can help clear some of these challenges, create more tolerant communicators, and contribute to achieving global sustainable goals.

Introduction

The United Nations established 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015 to transform the world by 2030 through simultaneously promoting prosperity and protecting the earth. The global body recognizes that culture directly influences development. Thus, SDG Goal 4.7 promotes “… a culture of peace and non-violence, global citizenship and appreciation of cultural diversity and of culture’s contribution to sustainable development.” Culture really matters (Seymour, 2007 ). Significantly, cultural cognition influences how people process information from different sources and suggests policies they may support or oppose (Rachlinski, 2021 ). Culture can drive sustainable development (United Nations, 2015 ; De Beukelaer and Freita, 2015 ; Kangas et al., 2017 ; Heckler, 2014 ; Dessein et al., 2015 ; and Hosagrahar, 2017 ).

UNESCO ( 2013 , p.iii ; 2017 , p.16; 2013a , p. 30) unequivocally states that “culture is a driver of development,” an “enabler of sustainable development and essential for achieving the 2030 Agenda” and as “an essential pillar for sustainable development.” These bold declarations have led to the growth of the cultural sector. The culture industry encourages economic growth through cultural tourism, handicraft production, creative industries, agriculture, food, medicine, and fisheries. Culture is learned social values, beliefs, and customs that some people accept and share collectively. It includes all the broad knowledge, beliefs, art, morals, law, customs, and other experiences and habits acquired by man as a member of a particular society. This seems to support Guiso, Paola and Luigi ( 2006 , p. 23) view of culture as “those customary beliefs and values that ethnic, religious, and social groups transmit fairly unchanged from generation to generation.” They assert that there is a causality between culture and economic outcomes. Bokova ( 2010 ) claims that “the links between culture and development are so strong that development cannot dispense with culture” and “that these links cannot be separated.” Culture includes customs and social behaviour. Causadias ( 2020 ) claims that culture is a structure that connects people, places, and practices. Ruane and Todd ( 2004 ) write that these connections are everyday matters like language, rituals, kingship, economic way of life, general lifestyle, and labour division. Field ( 2008 ) notes that even though all cultural identities are historically constructed, they still undergo changes, transformation, and mutation with time. Although Barth ( 1969 ) affirms that ethnicity is not culture, he points out that it helps define a group and its cultural stuff . The shared cultural stuff provides the basis for ethnic enclosure or exclusion.

The cultural identities of all men will never be the same because they come from distinctive social groups. Cultural identification sorts interactions into two compartments: individual or self-identification and identification with other people. Thus, Jenkins ( 2014 ) sees social identity as the interface between similarities and differences, the classification of others, and self-identification. He argues that people would not relate to each other in meaningful ways without it. People relate both as individuals and as members of society. Ethnicity is the “world of personal identity collectively ratified and publicly expressed” and “socially ratified personal identity‟ (Geertz, 1973 , p. 268, 309). However, the future of ethnicity has been questioned because culture is now seen as a commodity. Many tribal communities are packaging some aspects of their cultural inheritances to sell to other people who are not from their communities (Comaroff and Comaroff, 2009 ).

There is a relationship between culture and communication. People show others their identities through communication. Communication uses symbols, for example, words, to send messages to recipients. According to Kurylo ( 2013 ), symbols allow culture to be represented or constructed through verbal and nonverbal communication. Message receivers may come from different cultural backgrounds. They try to create meaning by interpreting the symbols used in communication. Miscommunication and misunderstanding may arise because symbols may not have the same meaning for both the sender and receiver of messages. If these are not efficiently handled, they may lead to stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination. Monaghan ( 2020 ), Zhu ( 2016 ), Holmes ( 2017 ), Merkin ( 2017 ), and Samovar et al. ( 2012 ) observe that inter-cultural communication occurs between people from different cultural groups. It shows how people from different cultural backgrounds can effectively communicate by comparing, contrasting, and examining the consequences of the differences in their communication patterns. However, communicating with others from different cultural backgrounds can be full of challenges, surprises, and re-learning because languages, values, and protocols differ. Barriers, like language and noise, impede communication by distorting, blocking, or altering the meaning.

Communication patterns change from one nation to the next. It is not uncommon, for example, for an American, a Nigerian, a Japanese national, or citizens of other countries to work together on a single project in today’s multi-cultural workplace. These men and women represent different cultural heritages. Martinovski ( 2018 ) remarks that both humans and virtual agents interact in cross-cultural environments and need to correctly behave as demanded by their environment. Possibly too, they may learn how to avoid conflicts and live together. Indeed, García-Carbonell and Rising ( 2006 , p. 2) remark that “as the world becomes more integrated, bridging the gap in cultural conflicts through real communication is increasingly important to people in all realms of society.” Communication is used to co-ordinate the activities in an organization for it to achieve its goals. It is also used to signal and order those involved in the work process.

This paper argues that barriers to cross-cultural communication can be overcome or significantly reduced if the actors in the communication processes become culture literates and competent communicators.

Statement of the problem

The importance of creating and maintaining good communication in human society cannot be overemphasized. Effective communication binds and sustains the community. Cross-cultural communication problems usually arise from confusion caused by misconstruction, misperception, misunderstanding, and misvaluation of messages from different standpoints arising from differences in the cultures of the senders and receivers of messages. Divergences in cultural backgrounds result in miscommunication that negatively limits effective encrypting, transmission, reception, and information decoding. It also hinders effective feedback.