- Issue Brief

Health Care Costs: What’s the Problem?

The cost of health care in the United States far exceeds that in other wealthy nations across the globe. In 2020, U.S. health care costs grew 9.7%, to $4.1 trillion, reaching about $12,530 per person. 1 At the same time, the United States lags far behind other high-income countries when it comes to both access to care and some health care outcomes. 2 As a result, policymakers and health care systems are facing increasing demands for more care at lower costs for more people. And, of course, everyone wants to know why their health care costs are so high.

The answer depends, in part, on who’s asking this question: Why does U.S. health care cost so much? Public policy often highlights and targets the total cost of the health care system or spending as a percentage of the gross domestic product (GDP), while most patients (the public) are more concerned with their own out-of-pocket costs and whether they have access to affordable, meaningful insurance. Providers feel public pressure to contain costs while trying to provide the highest-quality care to patients.

This brief is the first in a series of papers intended to better define some of the key questions policymakers should be asking about health care spending: What costs are too high? And can they be controlled through policy while improving access to care and the health of the population?

What (or Who) Is to Blame for the High Costs of Care?

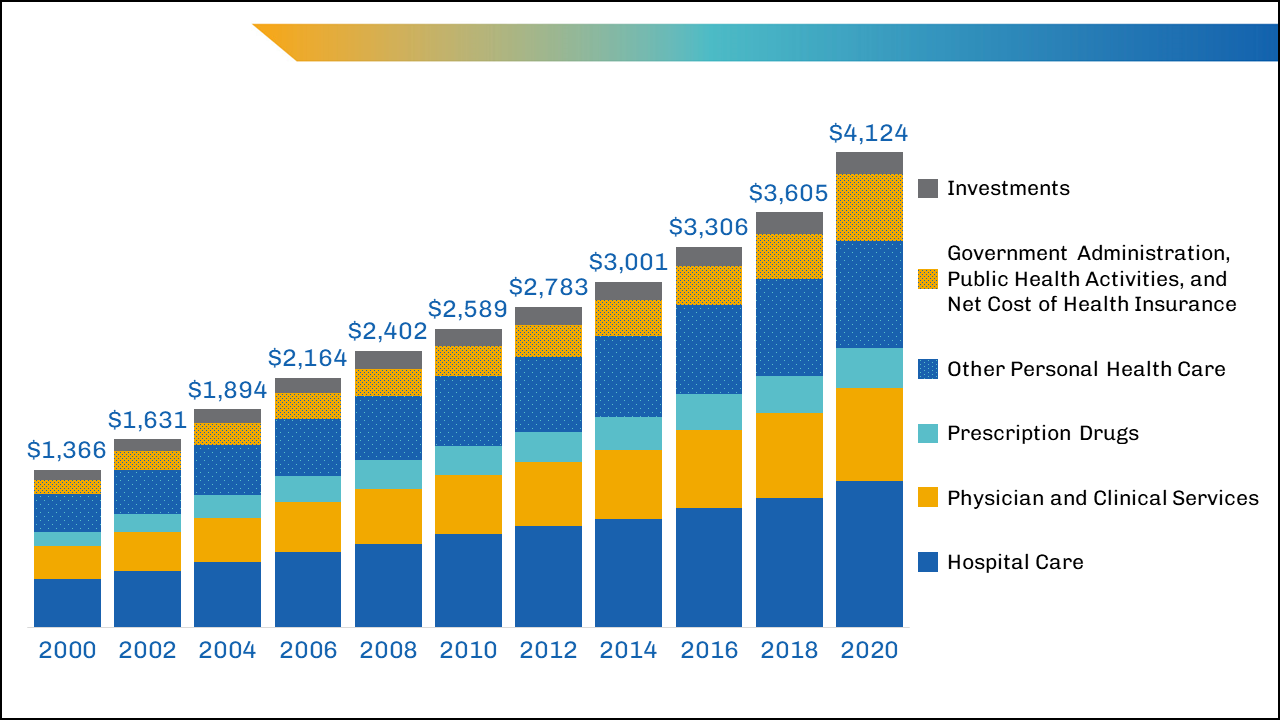

Total U.S. health care spending has increased steadily for decades, as have costs and spending in other segments of the U.S. economy. In 2020, health care spending was $1.5 trillion more than in 2010 and $2.8 trillion more than in 2000. While total spending on clinical care has increased in the past two decades, health care spending as a percentage of GDP has remained steady and has hovered around 20% of GDP in recent years (with the largest single increase being in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic). 1 Health care spending in 2020 (particularly public outlays) increased more than in previous years because of increased federal government support of critical COVID-19-related services and expanded access to care during the pandemic. Yet, no single sector’s health care cost — doctors, hospitals, equipment, or any other sector — has increased disproportionately enough over time to be the single cause of high costs.

One of the areas in health care with the highest levels of spending in the United States is hospital care, which has accounted for about 30% of national health care spending 3 for the past 60 years (and has remained very close to 31% for the past 20 years) (Figure 1). Although hospital spending is the focus of many cost-control policies and public attention, the increases are consistent with the increases seen across other areas of health care, such as for physicians and other professional services. Total spending for some smaller parts of nonhospital care has more than doubled over the past few decades and makes up an increasing proportion of total spending. For instance, home health care as a percentage of total spending tripled between 1980 and 2020, from 0.9% to 3.0%, and drug spending nearly doubled as a proportion of health care spending between 1980 and 2006, from 4.8% to 10.5%, and currently represent 8.4% of health care spending. 1

image description

The largest areas of spending that might yield the greatest potential for savings — such as inpatient care and physician-provided care — are unlikely to be reduced by lowering the total number of insured patients or visits per person, given the growing, aging U.S. population and the desire to cover more, not fewer, individuals with adequate health insurance.

In the past decade, policymaker and insurer interventions intended to change the mix of services by keeping patients out of high-cost settings (such as the hospital) have not always succeeded at reducing costs, although they have had other benefits for patients. 4

Breaking Down the Costs of Care

Thinking about total health care spending as an equation, one might define it as the number of services delivered per person multiplied by the number of people to whom services are delivered, multiplied again by the average cost of each service:

Health Care Spending=(number of services delivered per person)×(number of people to whom services are delivered)×(average cost of each service)

Could health care spending be lowered by making major changes to the numbers or types of services delivered or by lowering the average cost per service?

Although recent data on the overall utilization of health care are limited, in 2011, the number of doctor consultations per capita in the United States was below that in many comparable countries, but the number of diagnostic procedures (such as imaging) per capita remained higher. 5 Furthermore, no identifiable groups of individuals (by race/ethnicity, geographic location, etc.) appear to be outliers that consume extraordinary numbers of services. 6 The exception is that the sickest people do cost more to take care of, but even the most cost-conscious policymakers appear to be reluctant to abandon these patients.

In addition to the fact that the average number of health care services delivered per person in the United States was below international benchmarks in 2020,7 the percentage of people in the United States covered by health insurance was also lower than that in many other wealthy nations. Although millions of people gained insurance8 through the Affordable Care Act and provisions enacted during the COVID-19 pandemic, 10% of the nonelderly population remained uninsured in 2020. 9 When policymakers focus on reducing health care spending, considering the equation above, and see that the United States already has a lower proportion of its population insured and fewer services delivered to patients than other wealthy nations, their focus often shifts to the average cost of services.

It's Still the Prices … and the Wages

A report comparing the international prices of health care in 2017 found that the median list prices (charges) for medical procedures in the United States heavily outweighed the list prices in other countries, such as the United Kingdom, New Zealand, Australia, Switzerland, and South Africa. 10

For example, the 2017 U.S. median health care list price for a hospital admission with a hip replacement was $32,500, compared with $20,900 in Australia and $12,200 in the United Kingdom. In comparisons of the list prices of other procedures, such as deliveries by cesarean section, appendectomies, and knee replacements, the U.S. median list prices of elective and needed services were thousands of dollars — if not tens of thousands of dollars — more. 10 Yet, the list price for these services in the United States is often much higher than the actual payments made to providers by public or private insurance companies. 11

Public-payer programs (particularly Medicare and Medicaid) tend to pay hospitals rates that are lower than the cost of delivering care12 (though many economists argue these payments are slightly above actual costs, and providers argue they are at least slightly below actual costs), while private payers historically have paid about twice as much as public payers. 13 (See another brief in this series, “ Surprise! Why Medical Bills Are Still a Problem for U.S. Health Care ,” for more information about public and private payers’ role in health care costs.) However, the average cost per service is still high by international standards, even if it’s not as high as list prices may suggest. The high average costs are partially driven by the highly labor-intensive nature of health care, with labor consuming almost 55% of the share of total U.S. hospital costs in 2018. 14 These costs are growing due to the labor shortages exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Reducing U.S. health care spending by reducing labor costs could, theoretically, be achieved by reducing wages or eliminating positions; however, both of those policies would be problematic, with potential unintended consequences, such as driving clinicians away from the workforce at a time of growing need.

Wage reductions, particularly for clinicians, would require a vastly expanded labor pool that would take years to achieve (and even then, lower per person wages for nonphysicians may not decrease total spending related to health care labor). 15 Reducing or replacing clinical workers over time would require major changes to policy (both public and private) and major shifts in how health care is provided — neither of which has occurred rapidly, even since the implementation of the Affordable Care Act.

What’s a Policymaker to Do?

Nearly one in five Americans has medical debt, 16 and affordability is still an issue for a large proportion of the population, whether uninsured or insured, which suggests that policymakers should focus on patients’ costs. This may prove more impactful to the individual than reducing total health care spending.

A majority of the country agrees that the federal government should ensure some basic health insurance for all citizens. 17,18 Although most Americans consider reducing costs to individuals and expanding insurance coverage to be important, no clear consensus about who should bear any associated increased costs exists among patients or policymakers. Half of insured adults currently report difficulty affording medical or dental care, even when they are insured, because of the rising total costs of care and the increasing absolute amount of out-of-pocket spending. 19 Out-of-pocket spending for health care has doubled in the past 20 years, from $193.5 billion in 2000 to $388.6 billion in 2020. 1 These rising health care costs have disproportionately fallen on those with the fewest resources, including people who are uninsured, Black people, Hispanic people, and families with low incomes. 19 Increased cost sharing through copays and coinsurance may force difficult spending choices for even solidly middle-class families.

The severity and burden of out-of-pocket spending are hidden by the use of data averages; on average, U.S. residents have twice the average household net adjusted disposable income 20 of many other comparable nations and spend more than twice 21 as much per capita on health care. Yet, for those who fall outside these averages — average income, average costs, or both — the financial pain felt at the hospital, clinic, and pharmacy is very real.

In any given year, a small number of patients account for a disproportionate amount of health care spending because of the complexity and severity of their illnesses. Even careful international comparisons of end-of-life care for cancer patients demonstrate costs in the United States are similar to those in many comparable nations (although U.S. patients are more likely to receive chemotherapy, they spend fewer days in the hospital during the last 6 months of life than patients in other countries). 22 Similarly, although prevention efforts may delay or avoid the onset of illness in targeted populations, such efforts would not significantly reduce the number of services delivered for many years and may lead to an increase in care delivered over the course of an extended life span.

To the average person in the United States, immediate cost-control efforts might best be focused on reducing the cost burden for families and patients. Policymakers should continue to seek ways to promote better health care quality at lower costs rather than try to achieve unrealistic, drastic reductions in national health care spending. Investing in prevention, seeking to avoid preventable admissions or readmissions, and otherwise improving the quality of care are desirable, but these improvements are not quick solutions to lowering the national health care costs in the near term. Long-term policy actions could incrementally address health care spending but should clearly articulate the problem to be solved, the desired outcomes, and the trade-offs the nation is willing to make (as discussed in two companion pieces).

The U.S. health care system continues to place a disproportionate cost burden on the patients who can least afford it. In the short term, policymakers could focus on targeted subsidies to specific populations — the families and individuals whose household incomes fall outside the average or who have health care expenses that fall outside the average — whose health care costs are unmanageable. Such subsidies could expand existing premium subsidies or triggers that increase support for costs that exceed target amounts. Targeted subsidies are likely to increase total health care spending (especially public spending) but would address the problem of cost from the average consumer, or patient, perspective. Broader policies to ease costs for patients could also be considered by category of service; for instance, consumers have been largely shielded from the increased costs of care related to COVID-19 by the waiving of copays for patients and families. These policies would likely increase national spending as well, but they would make medical care more affordable to some families.

Download Brief

Cite this source: Grover A, Orgera K, Pincus L. Health Care Costs: What's The Problem? Washington, DC: AAMC; 2022. https://doi.org/10.15766/rai_dozyvvh2

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. National Health Expenditure Data. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NHE-Fact-Sheet . Published Dec. 1, 2021. Accessed Feb. 24, 2022.

- Schneider EC, Shah A, Doty MM, Tikkanen R, Fields K, Williams RD II. Mirror, Mirror 2021 — Reflecting Poorly: Health Care in the U.S. Compared to Other High-Income Countries. Washington, DC: The Commonwealth Fund. https://doi.org/10.26099/01DV-H208 . Published August 2021. Accessed April 21, 2022.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. National Health Expenditure Data: Historical. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsHistorical . Published Dec. 15, 2021. Accessed April 22, 2022.

- Berkowitz S, Ricks KB, Wang J, Parker M, Rimal R, DeWalt D. Evaluating a nonemergency medical transportation benefit for accountable care organization members. Health Affairs. 2022;41(3):406-413. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2021.00449.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Health Care Utilisation. Paris, France: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=30166# . Published Nov. 9, 2021. Accessed Feb. 24, 2022.

- Abelson R. Harris G. Critics question study cited in health debate. New York Times. June 2, 2010. https://www.nytimes.com/2010/06/03/business/03dartmouth.html?ref=business&pagewanted=all . Accessed Feb. 24, 2022.

- The Commonwealth Fund. Selected Health & System Statistics: Average Annual Number of Physician Visits per Capita. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/international-health-policy-center/system-stats/annual-physician-visits-per-capita . Published June 5, 2020. Accessed April 21, 2022.

- Tolbert J, Orgera K. Key Facts About the Uninsured Population. San Francisco, CA: KFF. https://www.kff.org/uninsured/issue-brief/key-facts-about-the-uninsured-population/ . Published Nov. 6, 2020. Accessed April 21, 2022.

- Tolbert J, Orgera K, Damico A. What Does the CPS Tell Us About Health Insurance Coverage in 2020? San Francisco, CA: KFF. https://www.kff.org/uninsured/issue-brief/what-does-the-cps-tell-us-about-health-insurance-coverage… . Published Sept. 23, 2021. Accessed April 21, 2022.

- Hargraves J, Bloschichak A. International Comparisons of Health Care Prices From the 2017 iFHP Survey. Washington DC: Health Care Cost Institute. https://healthcostinstitute.org/hcci-research/international-comparisons-of-health-care-prices-2017-ifhp-survey . Published Dec. 2019. Accessed April 21, 2022.

- Bai G. Anderson G. Extreme markup: The fifty US hospitals with the highest charge-to-cost ratios. Health Affairs. 2015;34(6):922-928. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1414.

- Congressional Budget Office. The Prices That Commercial Health Insurers and Medicare Pay for Hospitals’ and Physicians’ Services. Washington, DC: Congressional Budget Office. https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/2022-01/57422-medical-prices.pdf . Published January 2022. Accessed April 21, 2022.

- Lopez E, Neuman T, Jacobson G, Levitt L. How Much More Than Medicare Do Private Insurers Pay? A Review of the Literature. San Francisco, CA: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/how-much-more-than-medicare-do-private-insurers-pay-a-review-of-the-literature/ . Published April 15, 2020. Accessed March 22, 2022.

- Daly R. Hospitals Innovate to Control Labor Costs. Westchester, IL: Healthcare Financial Management Association. https://www.hfma.org/topics/hfm/2019/october/hospitals-innovate-to-control-labor-costs.html . Published Oct. 1, 2019. Accessed Feb. 24, 2022.

- Batson BN, Crosby SN, Fitzpatrick, JM. Mississippi frontline: Targeting value-based care with physician-led care teams. J Miss State Med Assoc. 2022;63(1):19-21. https://ejournal.msmaonline.com/publication/?m=63060&i=735364&p=20&ver=html5 .

- Kluender R, Mahoney N, Wong F, et al. Medical debt in the US, 2009-2020. JAMA. 2021;326(3):250-256. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.8694.

- Jones B. Increasing Share of Americans Favor a Single Government Program to Provide Health Care Coverage. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/09/29/increasing-share-of-americans-favor-a-single-government-program-to-provide-health-care-coverage/ . Published Sept. 29, 2020. Accessed April 21, 2022.

- Bialik K. More Americans Say Government Should Ensure Health Care Coverage. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/01/13/more-americans-say-government-should-ensure-health-care-coverage/ . Published Jan. 13, 2017. Accessed March 22, 2022.

- Kearney A, Hamel L, Stokes M, Brodie M. Americans’ Challenges With Health Care Costs. San Francisco, CA: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/health-costs/issue-brief/americans-challenges-with-health-care-costs/ . Published Dec. 14, 2021. Accessed Feb. 24, 2022.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Income. Better Life Index. Paris, France: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. https://www.oecdbetterlifeindex.org/topics/income/ . Accessed April 21, 2022.

- Wager E, Ortaliza J, Cox C; The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Health System Tracker. How Does Health Spending in the U.S. Compare to Other Countries? San Francisco, CA: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/health-spending-u-s-compare-countries-2/ . Published Jan. 21, 2022. Accessed April 21, 2022.

- Bekelman JE, Halpern SD, Blankart CR, et al. Comparison of site of death, health care utilization, and hospital expenditures for patients dying with cancer in 7 developed countries. JAMA. 2016;315(3):272-283. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.18603.

In her 2016 essay "Cost of Living" for the Virginia Quarterly Review — later anthologized in The Best American Essays — Emily Maloney unravels the juxtaposition of working to pay down her medical debt at a job where she assigns medical costs to treatments — costs that may, in turn, create the same kind of debt for others.

She writes of being 23 and working as an emergency room technician at a Chicagoland hospital, coding charts into bills, determining what to charge for the level of care each patient received: "Each level had its own exacting specifications, a way of making sense — at least financial sense — of the labyrinthine mess of billing."

But Maloney knew from her own experience that medical billing didn't actually compute in a financial sense. Four years earlier, she had been an ER patient at a hospital in Iowa City after a suicide attempt. That hospital stay resulted in a five-figure bill, one she could scarcely have imagined as a 19-year-old college student. "Sitting on a cot in the emergency room, I filled out paperwork certifying myself the responsible party for my own medical care — signed it without looking, anchoring myself to this debt, a stone dropped in the middle of a stream," Maloney writes.

"Cost of Living" — an indictment of the exorbitant costs of staying alive in America, and the weight of being hounded by a debt that reduces your life to dollars and cents — opens Maloney's debut essay collection of the same name. It's a powerful opening shot, but in the essays that follow, which recount Maloney's experiences as patient, caregiver, observer, and pharmaceutical industry worker, she stumbles before regaining the clarity of purpose and rigor of probing that "Cost of Living" promises.

There are 15 essays in Cost of Living , and the six that follow the titular piece feel as though they are narrated from underwater. Perhaps that is because they trace years in which Maloney herself felt that she had "not gotten the memo regarding how to be a person." She writes of being "too odd for elementary school, then secondary school," of attending seven schools in ten years, of difficulty conversing and maintaining eye contact, of seeing multiple psychologists at once.

Among the murkiest essays is "Clipped," which is at once about working as a dog groomer, deciding whether or not to apply to college, and feeling a need to escape her family. Maloney writes of her home life, "I knew something was wrong, that maybe there was a fire and everyone was inside the house." Something is wrong here, but that something is never clearly identified; I found myself waiting for retrospection that never came. "Clipped" feels, itself, clipped — an issue I had with several other essays, which put too much faith in the power of showing, not telling. "Some Therapy," for instance, is a list of 12 therapists, social workers, psychologists, and psychiatrists that Maloney saw, the reasons she was sent to them, and approximately how much they cost. "A Brief Inventory of My Drugs and Their Retail Price" is, well, what it sounds like. In these instances, I didn't know what to make of the litany: It is clear that both the therapy and the drugs weren't the treatment that Maloney actually needed, but unclear where she places the blame.

That Maloney does not even engage in any kind of questioning in these pieces is what makes them lack tension, fall flat. Later essays, where she takes up the same sort of thinking on the page that gives "Cost of Living" its verve, are far more compelling.

Among the best essays in the collection is "Soft Restraints," where Maloney finds a mirror in a woman she calls Elizabeth, who kept thrashing in her ER bed — and digs into the problem of female patients not being taken seriously. Elizabeth's chart labeled her as having borderline personality disorder and fibromyalgia, "a made-up diagnosis for us then, a kind of early aughts placeholder for female hysteria." In contrast is another woman who presents with "the worst headache of her life" and cannot stop crying. "Usually things like this were some kind of conversion disorder, or maybe psychosis," Maloney writes, but instead of resting in that assumption, this patient is sent for a CT scan that reveals a brain tumor the size of a small orange. Maloney herself ended up more like the "orange woman": she was eventually diagnosed correctly with a developmental disorder, hypothyroidism, and a vitamin deficiency, but realizes how she could have become Elizabeth: "It doesn't take much to get addicted to someone taking an interest in who you are, that sometimes all you are looking for is an answer, an explanation for why you feel this way, maybe a box to check or a space to occupy." This kind of zoom out and sustained inquiry is what I longed for in earlier pieces.

The essay that I cannot stop thinking about, though, is "Failures in Communication," where Maloney digs into the ethics of how physicians talk to patients about what is happening inside their bodies. Here, Maloney is no longer an ER tech but a pure observer in a teaching hospital in Pittsburgh, shadowing in an ICU step-down unit for a bioethics course she took while completing her MFA. This unit is where people go after they have survived intensive care, where "patients are responsive, awake, alert...but nevertheless very sick. This is the hardest part of patients and families to understand: that their loved one may still die, even though he seems fine."

In this liminal space between the worst of sickness and the beginning of what may be recovery or relapse, patients listen as medical students present their cases—explain what is keeping them in a hospital bed—to a group of residents, interns, attending physicians, and nurses during rounds. Medical students must "learn two languages, one for the patients and one for medicine." The language for patients isn't just medical jargon translated into what a layperson may understand, but a language with carefully regulated "nuance, tone, meter, facial expression," one that may include more or less information in order to manage the anxiety of patients and their family members. Writing of the case of woman whose husband always "assumes the worst," Maloney locates the conundrum that comes when translating from one language to another: "The information is incomplete, or they wait to tell the husband until they are sure they are going to do this procedure or that...Is making [patients] the last to know helping or hurting them? Where is the line?"

We will all someday land on the wrong side of the hospital bed, be at the mercy of caregivers who must determine how to treat us, how to talk to us, how to charge us. In the era of COVID — which Maloney touches on only briefly in the last essay — the precarity of health is all the more real. At its best, Cost of Living offers insight into the subculture of medicine and incites the reader to think more deeply about what our health care system is costing us all.

Kristen Martin's writing has also appeared in The New York Times Magazine, The Believer, The Baffler, and elsewhere. She tweets at @kwistent .

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

- US & World Economies

- GDP Growth & Recessions

The Rising Cost of Health Care by Year and Its Causes

See for yourself whether Obamacare increased health care costs

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/image0-MichaelBoyle-30f78c37d3174fe298f9407f0b5413e2.jpeg)

What Caused This Increase?

Government policy, preventable chronic diseases.

- Health Care Costs and the ACA

Inflation Reduction Act

Healthcare costs by year, frequently asked questions (faqs).

Sam Edwards / Getty Images

In 2020, U.S. health care costs totaled $4.1 trillion. That makes health care one of the country's largest expenses. Health spending accounted for 19.7% of the nation's gross domestic product (GDP).

In comparison, national health expenditures totaled $27.2 billion in 1960, just 5% of GDP. That translates to an annual health care cost of $12,530 per person in 2020 versus roughly $150 per person in 1960.

Keep reading to learn more about health expenditures and how the Affordable Care Act (ACA) aimed to control costs.

Key Takeaways

- Health care costs began rapidly rising in the 1960s as more Americans became insured and the demand for health care services surged.

- Health care costs have also increased due to preventable diseases, including complications related to nutrition or weight issues.

- Recent government attempts to stem the growth in health care costs include the Affordable Care Act and Inflation Reduction Act.

There were two causes of this massive increase: government policy and lifestyle changes.

Demand for Health Care Services

The government created programs like Medicare and Medicaid to help those without the private insurance most Americans rely upon. These programs spurred demand for health care services. That gave providers the ability to raise prices.

A study in Health Affairs co-authored by Princeton University health economist Uwe Reinhardt found that Americans use the same amount of healthcare as residents of other nations. They just pay more for them.

For example, U.S. hospital prices are 60% higher than those in other countries. Government efforts to reform healthcare and cut costs raised them instead.

Chronic Illnesses

Chronic illnesses, such as diabetes and heart disease, have increased. In 2020, the health care costs of people with at least one chronic condition were responsible for 86% of health care spending. More than half of all Americana adults have at least one of them.

These illnesses are expensive and difficult to treat. As a result, the sickest 5% of the population consumed 50% of total health care costs in 2019. The healthiest 50% only consumed 3% of the nation's health care costs.

The U.S. medical profession does a heroic job of saving lives, but it comes at a cost. Medicare spending for patients in the last year of life accounts for about 25% of the Medicare budget.

Between 1961 and 1965, health care spending increased by an average of 8.9% a year. That's because health insurance expanded. As it covered more people, the demand for health care services rose. By 1965, households paid out-of-pocket for 44% of all medical expenses. Health insurance paid for 24%.

From 1966 to 1973, health care spending rose by an average of 11.9% a year. Medicare and Medicaid covered more people and allowed them to use more health care services. Medicaid allowed senior citizens to move into expensive nursing home facilities.

As demand increased, so did prices. Health care providers put more money into research. It created more innovative, but expensive, technologies.

Medicare helped create an overreliance on hospital care. By 2012, there were 131 million emergency room visits. An astonishing one out of five adults used the emergency room that year.

In 1971, President Nixon implemented wage-price controls to stop mild inflation. Controls on health care prices created higher demand. In 1973, Nixon authorized Health Maintenance Organizations (HMO) to cut costs.

These prepaid plans restricted users to a particular medical group. The HMO ACT of 1973 provided millions of dollars in start-up funding for HMOs. It also required employers to offer them when available.

From 1974 to 1982, health care prices rose by an average of 14.1% a year for three reasons. First, prices rebounded after the wage-price controls expired in 1974. Second, Congress exempted some corporations from regulation with the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974, and companies offered lower-cost, flexible plans. Third, home health care took off, growing by 32.5% a year.

Between 1983 and 1992, health care costs rose by an average of 9.9% each year. Home health care prices increased by 18.3% per year.

In 1986, Congress passed the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act. It forced hospitals to accept anyone who showed up at the emergency room. Prescription drug costs rose by 12.1% a year. One reason is that the FDA allowed prescription drug companies to advertise on television.

Between 1993 and 2013, healthcare spending grew by an average of 6% a year.

In the early 1990s, health insurance companies tried to control costs by spreading the use of HMOs once again. Congress then tried to control costs with the Balanced Budget Act in 1997. Instead, it forced many healthcare providers out of business.

Because of this, Congress relented on payment restrictions in the Balanced Budget Refinement Act in 1999 and the Benefits Improvement and Protection Act of 2000. The act also extended coverage to more children through the Children's Health Insurance Program.

After 1998, people rebelled and demanded more choice in providers. As demand increased again, so did prices. Between 1997 and 2007, drug prices tripled, according to a study in Health Affairs.

One reason is that pharmaceutical companies invented new types of prescription drugs. They advertised straight to consumers and created additional demand. The number of drugs with sales that topped $1 billion increased to 52 in 2006 from six in 1997.

The U.S. government approved expensive drugs even if they were not much better than existing remedies. Other developed countries were more cost-conscious.

In 2003, the Medicare Modernization Act added Medicare Part D to cover prescription drug coverage. It also changed the name of Medicare Part C to the Medicare Advantage program, and the number of people using those plans increased to 28 million by 2022. Those costs rose faster than the cost of Medicare itself.

The nation’s reliance on the health insurance model increased administration costs. Various studies have found that administration makes up about 15% to 25% of U.S. healthcare costs. That's twice the administrative costs in Canada.

About half of those administrative costs in the U.S. are due to the complexity of billing. About half of those administrative costs in the U.S. are due to the complexity of billing. For example, in a 2018 JAMA study, U.S. physicians used 14.5% of their primary care revenue on administrative billing costs.

A big reason is that there are so many types of payers. In addition to Medicare and Medicaid, there are thousands of different private insurers. Each has its own requirements, forms, and procedures.

Hospitals and doctors must also chase down people who don't pay their portion of the bill. That doesn't happen in countries with universal healthcare .

The reliance on corporate private insurance created healthcare inequality . Those without insurance often couldn't afford visits to a primary care physician. By 2009, half of the people (46.3%) who visited an emergency room said they went because they had no other place to go for healthcare.

The Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act required hospitals to treat anyone who showed up in the emergency room. Uncompensated care costs hospitals more than $38 billion per year, some of which are passed on to the government.

The second cause of rising healthcare costs is an epidemic of preventable diseases. The four leading causes of non-accidental death are heart disease, cancer, COVID-19, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder, as of October 2022. Chronic health conditions cause most of them.

These issues can either be prevented or would cost less to treat if caught in time. Risk factors for heart disease and strokes are poor nutrition and obesity. Smoking is a risk factor for lung cancer (the most common type) and COPD. Obesity is also a risk factor for other common forms of cancer.

These diseases can cost more than $5,000 per person. The average cost of treating diabetes, for example, is $16,750 per person annually as of 2021.

These diseases are difficult to manage because patients get tired of taking the medications. Those who cut back find themselves in the emergency room with heart attacks, strokes, and other complications.

How the ACA Slowed the Rise of Healthcare Costs

By 2009, rising healthcare costs were consuming the federal budget. Medicare and Medicaid cost $671 billion in 2008. Payroll taxes cover less than half of Medicare and none of Medicaid.

This is part of so-called mandatory spending also generally includes federal and veterans' pensions , welfare, and interest on the debt . It consumed 60% of the federal budget. Congress knew something had to be done to rein in these costs.

Federal healthcare costs are part of the mandatory budget . That means they must be paid. As a result, they are eating up funding that could have gone to discretionary budget items, such as defense, education, or rebuilding infrastructure.

Obamacare's goal is to reduce these costs. First, it required insurance companies to provide preventive care for free so patients could treat chronic conditions before requiring expensive hospital emergency room treatments. It also reduced payments to Medicare Advantage insurers.

From 2010, when the Affordable Care Act was signed, through 2019, healthcare costs rose by 4.2% a year. It achieved its goal of lowering the growth rate of healthcare spending.

In 2010, the government predicted that Medicare costs would rise by 20% in just five years. That’s from $12,376 per beneficiary in 2014 to $14,913 by 2019. Instead, analysts were shocked to find out spending had dropped by over $1,200 per person, to $11,167 by 2014.

This price decrease happened due to four specific reasons:

- The ACA reduced payments to Medicare Advantage providers. The providers' costs for administering Parts A and B were rising much faster than the government’s costs. The providers couldn't justify the higher prices and appeared as though they were overcharging the government.

- Medicare began rolling out accountable care organizations, bundled payments, and value-based payments. Hospital readmissions dropped by 150,000 in both 2012 and 2013; hospitals increased efficiency and quality of care to avoid penalties for those who underperform.

- High-income earners paid more in Medicare payroll taxes and Part B and D premiums.

- In 2013, sequestration lowered Medicare payments by 2% to providers and plans.

Based on these new trends, Medicare spending was projected to grow by 7.9% a year between 2018 and 2028.

In 2022, the Inflation Reduction Act took effect. The wide-ranging bill included several components designed to soften the rise of health care costs for average consumers. While the details vary by state, the nationwide effects include capping prescription drug costs at $2,000, allowing Medicare to negotiate costs with drug companies, and limiting drug price hikes to the broader inflation rate.

Sources: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis.

Which tax supports healthcare costs for retirees?

The Medicare tax withheld from employee paychecks supports the cost of Medicare coverage for retirees. Employees and employers split the tax, and they each pay 1.45%. Self-employed individuals pay the full 2.9% Medicare tax themselves.

How do fraud and abuse impact the cost of healthcare?

Federal authorities have estimated that fraud accounts for between 3% and 10% of total healthcare spending. In 2017, for example, an audit found roughly $95 billion in improper Medicare and Medicaid spending. That's about 8% of the $1.1 trillion the government spent on health coverage programs.

FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. " Gross Domestic Product ."

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. " Historical ," Download "National Health Expenditures by Type of Service and Source of Funds, CY 1960-2020."

United States Census Bureau. " Historical Population Change Data (1910-2020) ."

Health Affairs. " It’s the Prices, Stupid: Why the United States Is So Different From Other Countries ."

OCED iLibrary. " Comparing Price Levels of Hospital Services Across Countries ."

Halsted R. Holman. " The Relation of the Chronic Disease Epidemic to the Health Care Crisis ." ACR Open Rheumatology .

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. " Chronic Diseases in America ."

Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker. " How Do Health Expenditures Vary Across the Population? "

Ian Duncan et al. " Medicare Cost at End of Life ." The American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Care .

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. " History of Health Spending in the United States, 1960-2013 ," Pages 7-9.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. " Emergency Department Use in the Country’s Five Most Populous States and the Total United States, 2012 ."

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. " History of Health Spending in the United States, 1960-2013 ," Pages 10, 15.

GovInfo. " Health Maintenance Organization Act of 1973 ."

U.S. Department of Labor. " ERISA ."

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. " History of Health Spending in the United States, 1960-2013 ," Page 12.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. " History of Health Spending in the United States, 1960-2013 ," Pages 14, 17.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. " Emergency Medical Treatment & Labor Act (EMTALA) ."

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. " History of Health Spending in the United States, 1960-2013 ," Pages 17, 33.

Julie Donohue. " A History of Drug Advertising: The Evolving Roles of Consumers and Consumer Protection ." The Milbank Quarterly .

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. " History of Health Spending in the United States, 1960-2013 ," Page 7.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. " History of Health Spending in the United States, 1960-2013 ," Pages 18-22.

Health Affairs. " Prescription Drug Spending Trends in the United States: Looking Beyond the Turning Point ."

Kaiser Family Foundation. " Medicare Advantage in 2022: Enrollment Update and Key Trends ."

National Center for Biotechnology Information. " Medicare Modernization: The New Prescription Drug Benefit and Redesigned Part B and Part C ."

JAMA Network. " Administrative Expenses in the US Health Care System: Why So High? "

Annals of Internal Medicine. " Health Care Administrative Costs in the United States and Canada, 2017 ."

The New England Journal of Medicine. " Costs of Health Care Administration in the United States and Canada ."

JAMA Network. " Administrative Costs Associated With Physician Billing and Insurance-Related Activities at an Academic Health Care System ."

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. " Emergency Room Use Among Adults Aged 18–64: Early Release of Estimates From the National Health Interview Survey, January–June 2011 ."

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. " Certification and Compliance for the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA) ," Page 1.

American Hospital Association. " Uncompensated Care Cost Fact Sheet ," Page 3.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. " Leading Causes of Death ."

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. " Heart Disease and Stroke ."

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. " What Are the Risk Factors for Lung Cancer? "

American Lung Association. " COPD Causes and Risk Factors ."

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. " Obesity and Cancer ."

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. " How Type 2 Diabetes Affects Your Workforce ."

National Academies Press. " 5 Options for Medicare and Medicaid ."

Congressional Research Service. " Mandatory Spending Since 1962 ," Page 7.

Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker. " How Has U.S. Spending on Healthcare Changed Over Time? "

Kaiser Family Foundation. " The Mystery of the Missing $1,200 Per Person: Can Medicare’s Spending Slowdown Continue? "

Health Affairs. " Recent Growth in Medicare Advantage Enrollment Associated With Decreased Fee-for-Service Spending in Certain US Counties ."

National Center for Biotechnology Information. " Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program ."

Kaiser Family Foundation. " What Are the Implications of Repealing the Affordable Care Act for Medicare Spending and Beneficiaries? "

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. " Additional Information Regarding the Mandatory Payment Reductions in the Medicare Advantage, Part D, and Other Programs ," Page 1.

Kaiser Family Foundation. " The Facts on Medicare Spending and Financing ."

Congress.gov. " H.R.5376 - Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 ."

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. " Historical ," Download "NHE Summary, Including Share of GDP, CY 1960-2018."

Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. " Consumer Price Index, 1913- ."

Internal Revenue Service. " Topic No. 751 Social Security and Medicare Withholding Rates ."

Health Affairs. " Combating Fraud in Health Care: An Essential Component of Any Cost Containment Strategy ."

Government Accountability Office. " Medicare and Medicaid: CMS Needs To Fully Align Its Antifraud Efforts With the Fraud Risk Framework. "

- University News

- Faculty & Research

- Health & Medicine

- Science & Technology

- Social Sciences

- Humanities & Arts

- Students & Alumni

- Arts & Culture

- Sports & Athletics

- The Professions

- International

- New England Guide

The Magazine

- Current Issue

- Past Issues

Class Notes & Obituaries

- Browse Class Notes

- Browse Obituaries

Collections

- Commencement

- The Context

- Harvard Squared

- Harvard in the Headlines

Support Harvard Magazine

- Why We Need Your Support

- How We Are Funded

- Ways to Support the Magazine

- Special Gifts

- Behind the Scenes

Classifieds

- Vacation Rentals & Travel

- Real Estate

- Products & Services

- Harvard Authors’ Bookshelf

- Education & Enrichment Resource

- Ad Prices & Information

- Place An Ad

Follow Harvard Magazine:

Features | Forum

The World’s Costliest Health Care

…and what America might do about it

May-June 2020

Americans use a lot of technologically sophisticated, expensive medical services—slighting more effective, routine care. Photograph by Rui Vieira/PA Wire/AP Images

L ONG BEFORE the presidential primaries, or a paralyzing pandemic, Harvard Magazine asked several faculty experts to write about issues that would be shaped by the national elections, that mattered to the future of the country—and that would probably be addressed inadequately during the extended campaign.

One issue was the federal budget and its chronic, enormous deficits. When we approached Karen Dynan and Douglas Elmendorf to explain all that red ink (and what, if anything, to do about it) , the state of play was an unlikely mix: a record U.S. economic expansion and very low unemployment, paradoxically accompanied by trillion-dollar annual deficits and historically low interest rates. Those figures now seem quaint. The coronavirus has caused a precipitous recession, or worse, and attempts to offset potentially cataclysmic job losses are yielding a multi-trillion-dollar budget gap that will need to be paid for some day; at the same time, government interest rates have fallen even further. In this context, Dynan and Elmendorf’s analysis is especially timely and relevant.

Spending on health care is central to the long-term budgetary challenges. So it is especially useful to pair their essay with David Cutler’s nuanced explanations of why American health care costs so much: about $3.5 trillion per year (that’s the norm , before an emergency like COVID-19)—of which one-third is wasted. The sources of that waste, in terms of health value received for dollars spent, may surprise you. It has certainly proven resistant to political repair. Given the relatively poor results Americans receive for all they spend, fixing health care matters: for citizens’ well-being, the country’s fiscal soundness, and extending essential medical services to those who lack access now.

Harvard Magazine presents these thoughtful commentaries as a service to readers—and as a contribution to better public debate. You can learn more from all three authors on their segments of the Ask a Harvard Professor podcast .

~ The Editors

* * *

A lec Smith died of diabetic ketoacidosis, though it is probably fairer to say that he died from high healthcare costs. The 26-year-old from Rochester, Minnesota, had just moved out of his parents’ home and didn’t have enough money to afford his insulin. He decided to ration his remaining supply until his next paycheck, a week later. Alas, he was not able to make it. Alec died alone in his apartment, vomiting and having difficulty breathing, from a condition that never should have occurred.

Alec’s story is extreme in its outcome, but not in its outlines. Nearly half of Americans say they have delayed or skipped medical care because of the cost. People who face higher costs for medical care are diagnosed with cancer at later stages of the disease and take fewer medications . Even the very sick use less care when their out-of-pocket costs rise. Health suffers .

A Medicare enrollee awaits a prescription in Chicago. The U.S. health system entails extraordinary administrative expenses. Photograph by Tim Boyle/Getty Images

The United States has many problems in medical care, from the large share of the population still uninsured (about 10 percent of us) to one of the lowest life expectancies in the developed world. Underlying all these problems is the high cost of medical care. We do not guarantee adequate access to medical care because we cannot figure out how to pay for it.

The harm from high medical spending goes well beyond the medical sector. Many firms have outsourced low-wage workers because providing them health benefits is too expensive. Government spending for schools and environmental programs are starved because resources go to health care instead. Warren Buffett called medical costs the “tapeworm of American economic competitiveness.” Oncologists have invented a term, “financial toxicity,” to consider along with biochemical toxicity in deciding on the appropriate treatment.

Americans agree with Buffett. Two-thirds of Americans want the federal government to regulate the price of medical care. Indeed, the public has a clear theory for explaining high medical spending: unconstrained greed. Pharmaceutical companies put profits above patients, and insurance executives are paid millions to deny coverage. The government should stop both.

And people are right, to a point. Allowing the makers of life-saving medications to price their products without constraint is a recipe for premature death. But the issue is more complex than just greed. Even if the United States cut every pharmaceutical price in half and eliminated all profits on health insurance, the gap between U.S. medical spending and that of other rich countries would fall by less than a quarter. Health care is more than just rapacious profits in drugs and insurance.

The reality is that the healthcare problem is multifaceted. But that is not the same as saying nothing can be done. On the contrary, it means there is even more to do. Three areas are essential to tackle if we want to reduce health spending to near the level in other countries.

Administration Adds Up

The largest component of higher U.S. medical spending is the cost of healthcare administration . About one-third of healthcare dollars spent in the United States pays for administration; Canada spends a fraction as much. Whole occupations exist in U.S. medical care that are found nowhere else in the world, from medical-record coding to claim-submission specialists.

Healthcare administration needn’t be so costly. Even in other countries with multiple payers and private providers—including Germany and Switzerland—healthcare administration is less than half the cost of the U.S. equivalent. The key requirement for reducing administrative costs is standardization. Grocery-store checkout is simple because all products have bar codes and credit-card machines are uniform. Mobile banking is easy because the Federal Reserve has put standards in place for how banks interface with each other. But every health insurer requires a different bar-code-equivalent and payment-systems submission. And even in 2020, it is virtually impossible to send medical records electronically from one hospital to another. Almost all hospitals have electronic medical records, but there is no federal requirement that they interface. Indeed, many providers take active steps to avoid electronic interchange, because keeping records local ensures that fewer patients will switch doctors.

Standardization occurs when big participants decide they want it. In healthcare, the big participant is the government. Only the federal government has the buying power and administrative reach to force payers and providers to adopt billing and interface rules. The federal government could commit to a date by which all interactions are standardized and set up the infrastructure to make that happen. To date, however, the public sector has shirked its responsibility. The federal government sees its role as providing insurance to people—Medicare and Medicaid in particular—but not looking out for the system as a whole. That thinking will need to change if progress is to be made.

Greed and Gouging

Greed is the second part of excessive health spending. The U.S. list price for insulin is 10 times higher than that in Canada. Relief for Alec could have come after a short bus ride north. But pharmaceuticals are not the whole story. Prestigious hospitals charge multiple times what less prestigious hospitals do for the same service. While that may be justified in the case of complex surgery, it surely is not for an x-ray.

It is no mystery why pharmaceutical prices are higher in the United States than in Canada and at star hospitals as compared to community institutions. Prices rise when there is nowhere else to go. Traveling to Canada for insulin is not something most Americans can do—though Alec Smith’s mother now leads such trips, or did when she was able to do so. And few people are willing to switch from a star hospital to a community institution, even if the price is much lower.

Economists’ favorite solution to such “sticky” demand is to help people become more mobile. Play different insulin suppliers off against each other to bargain for a lower price. Have interactive websites to help people shop for lower-priced imaging. Alas, all attempts to make these policies work have so far been unsuccessful. Many employers have created websites where their employees can search for more and less expensive services. Uniformly, they find that raising costs to patients via co-pays and deductibles, for example,reduces utilization but engenders relatively little price shopping. It is not that people think the star hospital is necessarily better. Rather, their physician directs them there, and they are afraid to ask about cheaper alternatives. Pharmaceuticals are a partial exception. People will often choose generic drugs, if available, over a brand name—but they do not do so in sufficient amounts to materially lower the cost of drugs. And federal laws make it illegal for bulk reimportation of drugs from Canada. The result is that star hospitals are overflowing with patients, and insulin prices keep rising.

If prices cannot be tamed by demand, a growing number of economists call for price regulation. Fiat can accomplish what reasoning cannot.

Price regulation is not hard to implement: “Thou shalt not price higher than X” is not a particularly difficult rule to enforce. The state of Maryland does this for hospitals, and most European countries do this for pharmaceuticals.

The major challenge to implementing such a policy is the possible unintended consequences. If pharmaceutical manufacturers or academic hospitals got less money, what would they cut out? Would executive compensation fall (likely a good thing)—or would money for research and development dry up? We are not certain of the answer to this, and so regulation comes with a side dose of concern. That said, every example of a family afraid to visit the emergency department because of the cost, and thus waiting to see if a sick child gets worse , pushes the case for price regulation forward.

In Love with Medical Services

The final part of higher medical spending in the United States is higher utilization . The United States has the most technologically sophisticated medical system of any country, and it shows up in spending: the U.S. has four times the number of MRIs per capita as Canada, and three times the number of cardiac surgeons. Americans don’t see the doctor any more often than Canadians do, and are not hospitalized any more frequently, but when they do interact with the medical system, it is much more intensively.

Outcomes for this greater intensity are not easy to find. Despite the more intensive U.S. cardiovascular care, heart-attack survival is no better. Indeed, U.S. death rates for heart disease have been rising relative to other rich countries. The greater degree of imaging in this country detects more cancers, but many of these would never have become clinically apparent. Many cancers grow slowly, and often the patient dies of something else long before the cancer would have become noticeable.

And even as the United States overdoes high-tech care, it underprovides routine care. Effective medications to treat high blood pressure and high cholesterol have been around for decades, yet only half of people with these risk factors are successfully treated. Mental illness is underdiagnosed and undertreated despite its enormous social cost.

The reason for the disparity between high-tech and routine care is not hard to ferret out. Cardiac surgery and MRIs—famously lucrative—are overprovided, but no one is paid to make sure hypertensive patients take their medications.

An uninsured father and son at a health clinic in Denver. Lack of coverage persists for a significant share of the population. Photograph by John Moore/Getty Images

Addressing the misallocation of medical resources is the most difficult technical challenge in lowering medical spending. How does one get a health system to perform fewer MRIs but do them on the right patients, and use the money saved to extend more primary care? The Canadian policy for overprovision is simple: limit the total amount of high-tech care available. Canadian governments ration the number of scanners that can be bought and how many hospitals can have open-heart surgery facilities. Within the available supply, physicians decide how the services are allocated. In a highly professional system like Canada’s, doctors perform the allocation rules very well. Thus, outcomes are better in Canada than in the United States, at a fraction of the cost.

The U.S. government once tried this type of technology rationing—it went by the name of Certificate of Need regulation. In the 1970s and 1980s, state governments had systems to approve each new scanner or addition to a hospital’s footprint and were supposed to say no when it was not necessary. But the policy was not very effective . Without a firm limit on what was allowed to be spent on medical care, it was too difficult for technology boards to deny hospitals. That set of policies has been left in the dustbin of failed cost-containment efforts.

Over time, insurers evolved other ways to try to restrict care. Some insurers have gone with a high cost-sharing strategy: make people pay more when they use care. Those willing to pay a higher cost can have the service. This is the strategy that leads to high out-of-pocket costs for insulin and emergency-department use. The second strategy is to keep an eagle eye on what physicians want to do, to make sure that all care is medically necessary. While good in theory, the administrative costs of this policy have proven to be a disaster.

The most recent economic idea is shared savings: don’t pay physicians a fee for each service, with higher rates for surgery and imaging than for medical management. Instead, set a target amount of spending for the average patient. If spending comes in below the target and quality is sufficiently high, the provider group gets to share in the savings. Thus, physicians have incentives to limit their own use of imaging to necessary cases and to figure out ways to extend primary-care practice. This policy was first tested in Massachusetts and has since gone national .

To date, there is no evidence that shared-savings programs will lead this country to the much lower Canadian or European levels of medical spending and better health outcomes.

The evidence so far is that shared savings programs have been modestly successful . Cost growth falls in shared-savings programs and quality seems to improve. But the savings are not as big as hoped for. To date, there is no evidence that shared-savings programs will lead this country to the much lower Canadian or European levels of medical spending and better health outcomes.

This discouraging record leads to deep questioning about how to make progress in medical care. Can the current system be a basis for good medical and economic outcomes, or must one make more radical change? Proponents of the latter view fall into two camps. On the left are those who reason that the only successful healthcare models internationally are single-payer systems, so the United States must move in that direction to do materially better. On the right are those who argue that only markets can provide the combination of price and quality that people want, so the country needs to remove government from the equation as much as possible. Not surprisingly, many Democrats espouse the former, and Republicans sign on to the latter.

In Rochester, Minnesota, and elsewhere in the country, people want none of this bigger debate. Phrases like “choice” and “single payer” are not helpful, let alone “incentives for interoperability of healthcare records.” Recall that Americans have a firm view of the problem: greed. Every conversation about something other than greed seems entirely beside the point.

This creates a special problem for the healthcare policymaker. In addition to figuring out what is technically correct, we need to learn how to explain those reforms to worried people. Can we promise that any policy will prevent deaths like Alec Smith’s and not harm people in other ways? Speaking morally, as well as economically, is the biggest challenge in health policy.

David Cutler is Eckstein professor of applied economics in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, professor in the department of global health and population at the School of Public Health, and a faculty member at the Harvard Kennedy School.

You might also like

“It’s Tournament Time”

Harvard women’s basketball prepares for Ivy Madness.

A Harvard Agenda Shaped by Speech

The work underway in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences

Dialogue, not Debate

American University’s Lara Schwartz, J.D. ’98, teaches productive disagreement.

Most popular

AWOL from Academics

Behind students' increasing pull toward extracurriculars

Why Americans Love to Hate Harvard

The president emeritus on elite universities’ academic accomplishments—and a rising tide of antagonism

More to explore

Winthrop Bell

Brief life of a philosopher and spy: 1884-1965

John Harvard's Journal

Talking about Talking

Fostering healthy disagreement

A Dogged Observer

Novelist and psychiatrist Daniel Mason takes the long view.

The Issue of Rising Medical Costs Essay

Healthcare policy initiative.

The healthcare industry is experiencing various issues and challenges that might affect the professionals’ performance, on stakeholders’ perception, and the quality of patient care. One of the problems that have a substantial impact on different aspects of healthcare is the issue of increased medical costs. The purpose of this paper is to investigate this challenge and its implications and propose a policy that will work towards overcoming the problem and improving the situation.

Rapid growth in medical costs can have various insinuations for the US population. Among them, it is possible to mention the fact that it will become more difficult for individuals to afford proper medical treatment and required drug purchases. The Centers for Medicare and Medical Services estimated that throughout the next ten years, healthcare costs would rise by more than 5% annually (“Healthcare costs for Americans,” 2019).

In such a way, the individuals might experience significant difficulties in affording such healthcare industry components, as hospital care or spending for prescribed drugs. Two factors are the most dominant in causing such a rapid increase. The prices for healthcare prices within the industry are rising, and the population of the nation is growing older, having a higher percentage of people aged over 65 (“Healthcare costs for Americans,” 2019). Consequently, those factors drive medical costs upward, which affects the way American families receive healthcare services.

Besides influencing the lives of patients, increased medical expenditures also have an impact on the work of healthcare professionals. The professionals can have challenges in offering the best solution in a situation when the patients who require extended treatment or expensive drug prescription. In attempts to provide the best healthcare service, the professionals might create further financial issues for the individuals.

Moreover, nurses and doctors can have moral worries when they can see that patients cannot afford the best cure for them. Therefore, employees within the healthcare industry can have psychological issues that might interfere with their performance in specific cases and cause higher turnover rates in the long-term.

One of the policies to advocate that will have a favorable impact on the overall situation in the future is the work on disease prevention. According to Cutler (2017), this policy “is both healthier for the individual and less expensive for the system” (p. 508). Thus, with a higher chance of avoiding specific diseases, the individuals would not need such extensive medical care, and the system will have lower expenditures for the treatment.

For example, new drugs for hypertension and high cholesterol have substantially reduced the likelihood of cardiovascular diseases, which implicates lower spending on treatment and medication (Cutler, 2017). Consequently, finding medicines to reduce the number of other chronic illnesses can decrease specific medical costs.

Still, disease prevention is a long-term policy, the effects of which might not be evident right away. While actively integrating disease prevention strategies, the industry can use such approaches as cutting prices for the drugs and offering bundling payment options for the individuals (Cutler, 2017). Those techniques can lower the financial burden for the patients and make them more willing to come and seek medical treatment without fear of not being able to pay for it.

It is crucial to employ an effective campaign to address the current issue and propose the policy and approaches aiming to improve the situation. Advocating the problem and suggested solutions through social media and reaching pharmaceutical companies, as well as integrating bundled payment options within specific healthcare facilities, can be the first step.

The Twitter post to highlight the problem can be: With CMS estimating a rapid growth in medical costs, it is critical to cut the pharmaceutical prices and integrate bundled payments. In conclusion, the issue of growing expenditures in the healthcare industry presents severe challenges for all the parties involved, and there is a need for action to change the situation.

Cutler, D. M. (2017). Rising medical costs mean more rough times ahead. Jama , 318 (6), 508-509.

Healthcare costs for Americans projected to grow at an alarmingly high rate . (2019). Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, May 20). The Issue of Rising Medical Costs. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-issue-of-rising-medical-costs/

"The Issue of Rising Medical Costs." IvyPanda , 20 May 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/the-issue-of-rising-medical-costs/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'The Issue of Rising Medical Costs'. 20 May.

IvyPanda . 2022. "The Issue of Rising Medical Costs." May 20, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-issue-of-rising-medical-costs/.

1. IvyPanda . "The Issue of Rising Medical Costs." May 20, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-issue-of-rising-medical-costs/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "The Issue of Rising Medical Costs." May 20, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-issue-of-rising-medical-costs/.

- U.S. Healthcare System and Organizational Structures

- American Healthcare Services Payment Differences

- Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing Intervention

- Hotel Services and Pricing Strategies

- Promoting Equity With Healthcare Reforms

- Physician-Hospital Arrangements and Development in the Healthcare Industry

- Relationship Between Doctors and Pharmaceutical Industries

- Facilitation of Sun Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd

- Pharmaceutical Industry and Drugs

- Practices in the Pharmaceutical Industry

- Need Assessment and GAP Analysis Mayo Clinic

- Process of Funding Acute Inpatient Services

- Zero Based Budgeting (ZBB) Overview

- Financing Health Care in US Cost vs. Quality

- IRS Regulations and Healthcare

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

- Overall Healthcare Costs

Why Are Healthcare Costs Rising?

The aging population, increase in chronic illnesses, increased ambulatory costs, rising insurance premiums.

- RRising Government Costs

Higher Out-of-Pocket Costs

The fear factor, cost of covid-19, patching u.s. healthcare, the bottom line.

- Health Insurance

Why Do Healthcare Costs Keep Rising?

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/jp_profileinv__jim_probasco-5bfc262746e0fb005118b333.jpg)

Ariel Courage is an experienced editor, researcher, and former fact-checker. She has performed editing and fact-checking work for several leading finance publications, including The Motley Fool and Passport to Wall Street.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/ArielCourage-50e270c152b046738d83fb7355117d67.jpg)

Americans now spend close to $13,000 on average on healthcare each year. High insurance premiums, high deductibles, and other out-of-pocket expenses are just some of the costs associated with health and wellness in the country, and those costs are only going higher.

One reason for rising healthcare costs is government policy. Since the inception of Medicare for retired Americans and Medicaid for low-income people, providers have been able to increase prices with the knowledge that the government, not the individual, will be paying the bills.

Still, there’s much more to rising healthcare costs lately, including the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the cost structure.

Key Takeaways

- Healthcare costs in the United States have been rising for decades and are expected to keep increasing.

- Nearly 18% of U.S. GDP went to healthcare in 2021, almost twice other developed nations despite comparatively poor results for patients.

- In the long term, the financial impact of COVID-19-related healthcare spending is not expected to significantly affect healthcare spending in general.

- The No Surprises Act and other recent legislation offer some help when it comes to unexpected healthcare billing.

Overall Costs of Healthcare

Healthcare costs have risen dramatically in the United States over the past several decades. According to the Commonwealth Fund, healthcare spending as a percentage of GDP rose from 8.2% in 1980 to 17.8% in 2021.

Americans are not getting better outcomes for their money compared to their peers. Americans had the highest death rate due to COVID-19 among its peer nations. They have a lower life expectancy, a higher rate of avoidable deaths, and the highest rates of infant and maternal deaths.

But the costs in dollars are only going up. In 2023, healthcare spending is expected to rise by 5.1%, from $4.2 trillion in 2022, according to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Where does that money go? According to the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), healthcare spending can be broken down into 10 categories:

- Hospital care (31%)

- Physician services (20%)

- Prescription drugs (10%)

- Other personal healthcare costs (5%)

- Nursing care facilities (5%)

- Dental services (4%)

- Home healthcare (3%)

- Other professional services (3%)

- Other non-durable medical products (2%)

- Durable medical equipment (2%)

A 2023 study by the Peter G. Peterson Foundation blamed rising prices on three big factors: population growth, population aging, and rising prices for healthcare products and services.

An earlier study by the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) adds additional factors, citing an increase in chronic illnesses and the rising costs of health insurance, among others.

Protection Against Rising Costs

The No Surprises Act and other legislation contained in the Consolidated Appropriations Act (CAA), 2021, are designed to protect consumers from a lack of transparency in healthcare billing. This legislation took effect on Jan. 1, 2022.

Healthcare gets more expensive as the population expands, particularly when the growth is attributable to longer lifespans.

Older people spend more on healthcare than younger people, and they tend to require more expensive procedures, such as knee replacements and heart bypass surgery.

Americans aged 65 and over represented 16% of the population in 2021, and that number is expected to reach 20% by 2030.

Therefore, it’s not surprising that 50% of the increase in healthcare spending comes from increased costs for services, especially inpatient hospital care.

The authors of the JAMA study point to diabetes as the medical condition responsible for the greatest increase in spending over the study period, which was 1996 through 2013.

The increased cost of diabetes medications alone was responsible for $44.4 billion of the $64.4 billion increase in costs to treat that disease.

After diabetes, conditions with the greatest increase in costs were:

- Lower back and neck pain: $57.2 billion

- High blood pressure: $46.6 billion

- High cholesterol: $41.9 billion

- Depression: $30.8 billion

- Urinary disease: $30.2 billion

- Osteoarthritis: $29.9 billion

- Bloodstream infection: $26 billion

- Falls: $26 billion

- Oral disease: $25.3 billion

Ambulatory care, including outpatient hospital services and emergency room care, increased the most of all treatment categories studied.

To some extent, that is a transferral of services from inpatient hospital care to outpatient care.

The trend speeded up during the COVID-19 pandemic when healthcare providers moved to virtual services to avoid crowded waiting rooms.

The average annual premium for health insurance in 2022 was $7,911 for single people. For family coverage, it averaged $22,463 for family coverage, a 43 percent increase since 2012.

The high cost of American health insurance has a number of causes. The website eHealth cites administrative costs, increasing prices for prescription drugs, and "lifestyle choices."

Rising Government Costs

Nearly 92% of Americans now have health insurance.

That's the good news.

Government programs like Medicare, Medicaid, and the Affordable Care Act have increased overall demand for medical services, resulting in higher prices as well.

What’s more, increases in the incidence of chronic conditions such as diabetes and heart disease, especially among seniors, have had a direct impact on increases in the cost of medical care. Chronic diseases constitute 85% of healthcare costs, and more than half of all Americans have a chronic illness.

Higher insurance premiums are only part of the picture. Americans are paying more out of pocket than ever before.

A shift to high-deductible health plans (HDHPs) that require out-of-pocket payments of up to $14,000 per family has added greatly to the cost of healthcare.

Employer contributions to HDHPs help to mitigate the higher deductible. According to one study, HDHP enrollees paid 20% of their total premium while preferred provider organization (PPO) enrollees paid up to 27% of theirs.

Avoidance of medical care due to concerns about unpredictable costs has been a problem for some years. A 2019 survey by the Physicians Advocacy Institute (PAI) found patients avoiding care due to anxieties about the potential costs of deductibles under their HDHPs.

The COVID-19 pandemic made it worse. A Kaiser Family Foundation poll suggests that up to 50% of the public has either avoided or postponed medical care due to concerns about exposure to COVID-19, further exacerbating the problem.

Avoiding care results in higher overall healthcare costs, as the delay makes treatable conditions more costly to treat.

COVID-19, with the increased need for testing, treatment, and care, was expected to change the cost of healthcare, although experts didn't agree on whether it would cause costs to rise or fall.

In fact, early on, healthcare spending fell, mostly due to patients postponing treatment for other illnesses. More recently, utilization and spending have rebounded.

In the grand scheme of things, COVID may not alter the trajectory of healthcare spending a great deal. Though short-term spending fell, it is expected to grow at an average annual rate of 5.4% and reach $6.2 trillion by 2028.

There have been recent attempts to patch the U.S. healthcare system. In particular, they address the lack of transparency that drives some people to avoid going to the doctor and others saddled with unexpected debt.

Lack of Transparency

From the view of the consumer, it’s difficult to predict the actual cost of healthcare. Most people know the cost of care is going up, but with few details and complicated medical bills, it’s not easy to know what you’re getting for your money.

That lack of transparency in healthcare was addressed in the Consolidated Appropriations Act (CAA) of 2021. One section of this act removes gag clauses related to price and quality information. Another, targeting health insurance, requires disclosure of direct and indirect compensation for brokers and consultants to the insurance companies.

The law became effective on Jan. 1, 2022.

The No Surprises Act