The Power of Narrative Writing

by Melissa Donovan | Feb 4, 2021 | Creative Writing | 6 comments

What is narrative writing, and why is it so powerful?

The secret is out: narrative is powerful.

A narrative can entertain, inform, and persuade — but most importantly, it can forge deep, meaningful, and lasting connections.

What is Narrative Writing?

A narrative is a spoken or written account of events. The word narrative is often used interchangeably with story , because a narrative is structured like a story: it has a beginning, a middle, and an end (although it’s not always presented in that order). A narrative can be true or fictional.

Narrative writing is the act of crafting a written narrative (or story), real or imagined. Here are a few different types of written narratives:

- Novels, films, television shows, and plays are narratives.

- A narrative essay is written like a short story, but it’s an account of real events whereas a short story is fictional.

- A short story is also a narrative.

- Narratives also appear in speeches, advertisements, lectures, and even in personal encounters.

- Have you ever shared a personal story about your life with someone? That was your narrative.

- Personal essays, memoirs, and autobiographies are narratives.

We also use the word narrative when discussing how a story is written and structured. We might say that a narrative is messy or tight, that it lacks consistency, or that it’s long and winding.

Narrative writing opportunities abound in industries in which stories are told. Some examples include filmmaking and television, marketing, and politics (speech writing).

But we all use narrative: stories are everywhere.

What is the Power of Narrative?

The word narrative is often thrown around by the media, politicians, and commercial enterprises. They understand the power of narrative, which can be used to spread a message, cultivate emotional connections, and control a story in the cultural landscape; in fact, narratives shape culture. Stories have a profound effect on people, from a single individual to the widespread masses.

Let’s look at some examples of the power of narrative:

Telling True Stories (aff link).

Narrative Changes the World: Consider Malala Yousafzai, a young Pakistani girl who was shot in the head at age fifteen because she wanted to go to school. Malala survived and went on to become a world-renowned advocate for education, focusing on regions of the world where girls are deprived of schooling. Malala’s story, or narrative, was instrumental in making the world stage available to her so she could broadcast her message to the masses and affect positive change. In 2014, she won the Nobel Peace Prize.

Narrative Creates Celebrity: Some celebrities excel at using narrative to build their brands and cultivate fans. Watch any music competition show and you’ll see the contestants sharing their life stories, often emphasizing the difficulties or conflicts they’ve experienced. It’s been said before: conflict is story . When audiences see these contestants’ struggles, they want to root for them, and a fandom begins to blossom. Throughout a celebrity’s career, the narrative continues, as we watch their highs and lows. It can be a long, ongoing narrative that keeps the fans tuned in and buying books, movies, music, magazines, tickets, and more.

Narrative Wins Races: Politicians use narrative to build emotional and intellectual connections with the public, and as a tool of persuasion, but they are often more invested in controlling the story than sharing it. As they reveal their life stories to us, politicians pick and choose which bits to include, forging a selective narrative that emphasizes their strengths while downplaying their weaknesses. And the best narrative often wins while an unappealing or disagreeable narrative is a losing proposition.

Narrative Sells: Watch some commercials to see narrative being used to sell products and services. In advertising, stories are often presented as problems, with the product as the solution: After years of itchy razor burn, a young man finally finds a razor that leaves his face clear and smooth. Ads feature narratives that a target demographic can relate to, which is why commercials sell millions of products ranging from food and cleaning supplies to computers and makeup and life-insurance policies.

Narrative Teaches: In high school, I had a history teacher who stood at the front of the class, reading aloud from a dry textbook that was written strictly to impart information — certainly not to engage. A few years later, I took a history class in college with a professor who sat casually on the edge of his desk, relaying the events of history as if we were all sitting rapt around a campfire and he was our master storyteller. Guess which lessons stayed with me?

Narrative Bonds: Narrative is one of the key elements of a relationship. As you get to know someone, you learn about their life and a narrative starts to form. You use that narrative to understand and relate to the other person. We also share in each other’s narratives as we participate in each other’s lives. You are the main character in your life story, but there are many other characters surrounding you, from sidekicks to nemeses. The roles we play in each other’s narratives bind us together. We are all threads in a massive tapestry of a narrative.

Why We Love Narrative

Wired for Story (aff link).

Whether we’re buried in books or ogling at screens, we love to immerse ourselves in narratives. Why is that?

An article on Wired titled “ The Art of Immersion: Why Do We Tell Stories? ” delves into the science behind why we love stories so much:

Anthropologists tell us that storytelling is central to human existence. That it’s common to every known culture. That it involves a symbiotic exchange between teller and listener — an exchange we learn to negotiate in infancy. Just as the brain detects patterns in the visual forms of nature — a face, a figure, a flower — and in sound, so too it detects patterns in information. Stories are recognizable patterns, and in those patterns we find meaning. We use stories to make sense of our world and to share that understanding with others. They are the signal within the noise.

So how do we find meaning in stories? How do we use stories to make sense of our world? Let’s look to fictional and personal narratives for the answers:

Personal (Nonfiction) Narratives: Storytelling is used in memoirs and documentaries to convey true stories. When we hear about a devastating natural disaster on the other side of the world that affected thousands of people, it’s difficult to put it into context. But when we hear firsthand accounts from survivors who describe what it was like to witness and experience the disaster — when we hear their narratives — we can better relate to the events that transpired. We begin to understand what it was like to be there, and our empathy gets engaged.

Fictional Narratives: Fiction is probably the most beloved form of narrative writing and story consumption. Books, movies, television shows, and video games give us made-up stories. Whether a historical novel that carries us into the past so we can gain insight on what it might have been like to live in a world without technology or a science-fiction film that takes us far into the future where technology has surpassed our wildest imaginations, fictional narratives, like true narratives, give us access to experiences that we’ll never have and allow us to gain better understanding of the world we live in, and in some cases, the world we might someday live in.

The most successful narratives make the audience feel something. Let me say that again: the most successful narratives make the audience feel something . It is a narrative’s ability to evoke emotion (and it can be any emotion) that determines its impact on individuals and groups. Narrative can make us laugh or cry, terrify or mystify us. They can fill us with awe and wonder and glory. Perhaps you’ve heard the old adage: “People will forget what you said and what you did, but they’ll never forget how you made them feel.”

Therein lies the greatest power of narrative: its impact on our emotions.

The Science of Narrative

Scientists have examined the power of narrative and made some fascinating discoveries, most of which confirm the experiences that we’ve all had with books, movies, and other forms of storytelling. It turns out that narrative directly affects the human brain, and its effects can be measured :

- Narrative changes our brain activity.

- It increases oxytocin synthesis, which increases empathy, trust, kindness, and cooperation.

- It alters our emotional state, aligning it with the narrative we’re experiencing.

- It improves recall and increases attention.

That is real, proven power.

But let’s get back to our business — the business of writing.

A Guide to Narrative Writing

But how do we go about writing a good narrative?

There are several key elements that we find in successful narrative writing, which you can use as a guide while crafting a narrative of your own:

- Setting: The backdrop of a narrative sets the stage and helps the audience enter a story world. Setting is crucial, even if it only takes a few words to establish.

- Characters: They can be made-up characters or real people. Audiences develop relationships with characters; it is through this bond that we connect with stories on an emotional level.

- Conflict: All the best narratives are built around a core conflict or story question. We stay tuned in because we want see how the conflict gets resolved. We want to find out the answers to questions that the story poses and see how the characters solve the problems they’ve encountered.

- Rising tension: As a narrative progresses, the tension increases. There are peaks and valleys, but the tension ultimately rises until the narrative reaches its climax.

- Plot: Plot is what happens (the beats of a story) as the narrative follows an arc that has a beginning, a middle, and an end. Arcs almost always result in meaningful transformation, which is one of the most appealing elements of narrative.

- Action and dialogue: Action and dialogue are how we experience a narrative. The characters say and do things that move the plot forward.

- Point of view: Who’s telling the story? The voice of the narrative sets the tone for the tale. The narrative point of view gives us a particular perspective on the events taking place.

As you pursue narrative writing, ask whether you’re including these essential elements and whether they’re woven together seamlessly.

Have you tried your hand at narrative writing? What kind of narrative did you write? Did you aim to educate and inform, share your thoughts and ideas, or entertain audiences? Share your experiences with narrative writing by leaving a comment, and keep writing!

Ideal way to kick off a dull damp Thursday morning. Thank You.

Thank you for this article, am a reaseacher and using narrative ✍️ 🔡 📝 ✍️

You’re welcome!

Excellent. Clear, to the point and easy to understand. I loved it. Thank you for writing it.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

- Top Picks Thursday! For Writers & Readers 02-11-2021 | The Author Chronicles - […] Donovan explains the power of narrative writing, Stephen D. Rogers urges us to write better and sell more by…

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Subscribe and get The Writer’s Creed graphic e-booklet, plus a weekly digest with the latest articles on writing, as well as special offers and exclusive content.

Recent Posts

- Poetry Writing Exercises in Space and Time

- How to Break Through a Fiction Writing Block

- Grammar Rules: That and Which

- What’s in Your Creative Writing Notebook?

- Writing and Editing Polished Prose

Write on, shine on!

Pin It on Pinterest

Narrative Writing: A Complete Guide for Teachers and Students

MASTERING THE CRAFT OF NARRATIVE WRITING

Narratives build on and encourage the development of the fundamentals of writing. They also require developing an additional skill set: the ability to tell a good yarn, and storytelling is as old as humanity.

We see and hear stories everywhere and daily, from having good gossip on the doorstep with a neighbor in the morning to the dramas that fill our screens in the evening.

Good narrative writing skills are hard-won by students even though it is an area of writing that most enjoy due to the creativity and freedom it offers.

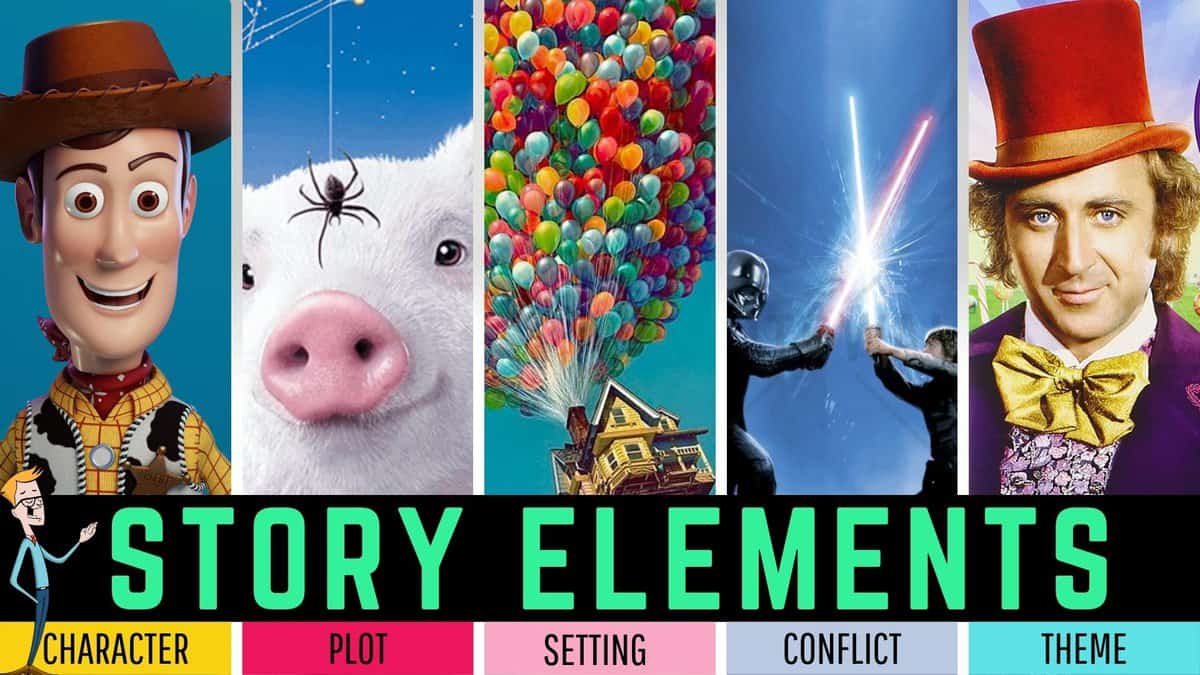

Here we will explore some of the main elements of a good story: plot, setting, characters, conflict, climax, and resolution . And we will look too at how best we can help our students understand these elements, both in isolation and how they mesh together as a whole.

WHAT IS A NARRATIVE?

A narrative is a story that shares a sequence of events , characters, and themes. It expresses experiences, ideas, and perspectives that should aspire to engage and inspire an audience.

A narrative can spark emotion, encourage reflection, and convey meaning when done well.

Narratives are a popular genre for students and teachers as they allow the writer to share their imagination, creativity, skill, and understanding of nearly all elements of writing. We occasionally refer to a narrative as ‘creative writing’ or story writing.

The purpose of a narrative is simple, to tell the audience a story. It can be written to motivate, educate, or entertain and can be fact or fiction.

A COMPLETE UNIT ON TEACHING NARRATIVE WRITING

Teach your students to become skilled story writers with this HUGE NARRATIVE & CREATIVE STORY WRITING UNIT . Offering a COMPLETE SOLUTION to teaching students how to craft CREATIVE CHARACTERS, SUPERB SETTINGS, and PERFECT PLOTS .

Over 192 PAGES of materials, including:

TYPES OF NARRATIVE WRITING

There are many narrative writing genres and sub-genres such as these.

We have a complete guide to writing a personal narrative that differs from the traditional story-based narrative covered in this guide. It includes personal narrative writing prompts, resources, and examples and can be found here.

As we can see, narratives are an open-ended form of writing that allows you to showcase creativity in many directions. However, all narratives share a common set of features and structure known as “Story Elements”, which are briefly covered in this guide.

Don’t overlook the importance of understanding story elements and the value this adds to you as a writer who can dissect and create grand narratives. We also have an in-depth guide to understanding story elements here .

CHARACTERISTICS OF NARRATIVE WRITING

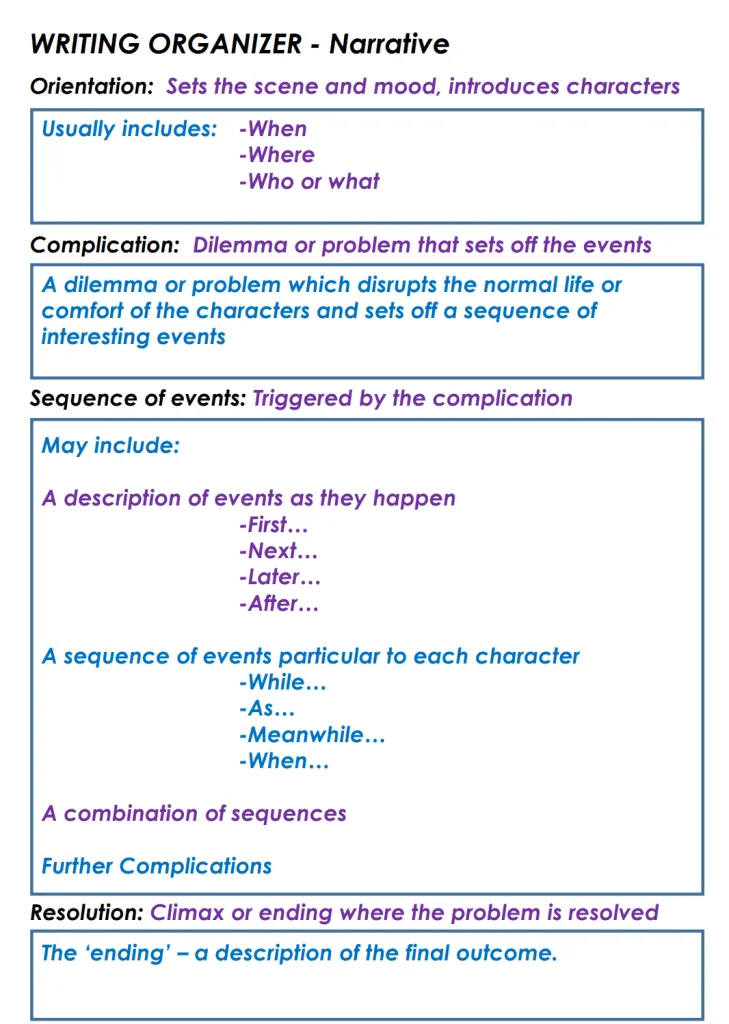

Narrative structure.

ORIENTATION (BEGINNING) Set the scene by introducing your characters, setting and time of the story. Establish your who, when and where in this part of your narrative

COMPLICATION AND EVENTS (MIDDLE) In this section activities and events involving your main characters are expanded upon. These events are written in a cohesive and fluent sequence.

RESOLUTION (ENDING) Your complication is resolved in this section. It does not have to be a happy outcome, however.

EXTRAS: Whilst orientation, complication and resolution are the agreed norms for a narrative, there are numerous examples of popular texts that did not explicitly follow this path exactly.

NARRATIVE FEATURES

LANGUAGE: Use descriptive and figurative language to paint images inside your audience’s minds as they read.

PERSPECTIVE Narratives can be written from any perspective but are most commonly written in first or third person.

DIALOGUE Narratives frequently switch from narrator to first-person dialogue. Always use speech marks when writing dialogue.

TENSE If you change tense, make it perfectly clear to your audience what is happening. Flashbacks might work well in your mind but make sure they translate to your audience.

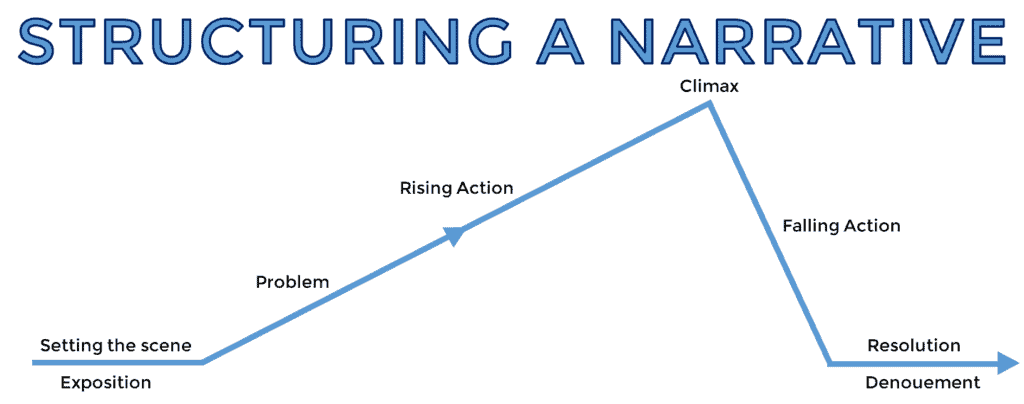

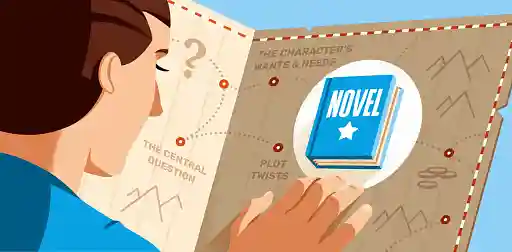

THE PLOT MAP

This graphic is known as a plot map, and nearly all narratives fit this structure in one way or another, whether romance novels, science fiction or otherwise.

It is a simple tool that helps you understand and organise a story’s events. Think of it as a roadmap that outlines the journey of your characters and the events that unfold. It outlines the different stops along the way, such as the introduction, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution, that help you to see how the story builds and develops.

Using a plot map, you can see how each event fits into the larger picture and how the different parts of the story work together to create meaning. It’s a great way to visualize and analyze a story.

Be sure to refer to a plot map when planning a story, as it has all the essential elements of a great story.

THE 5 KEY STORY ELEMENTS OF A GREAT NARRATIVE (6-MINUTE TUTORIAL VIDEO)

This video we created provides an excellent overview of these elements and demonstrates them in action in stories we all know and love.

HOW TO WRITE A NARRATIVE

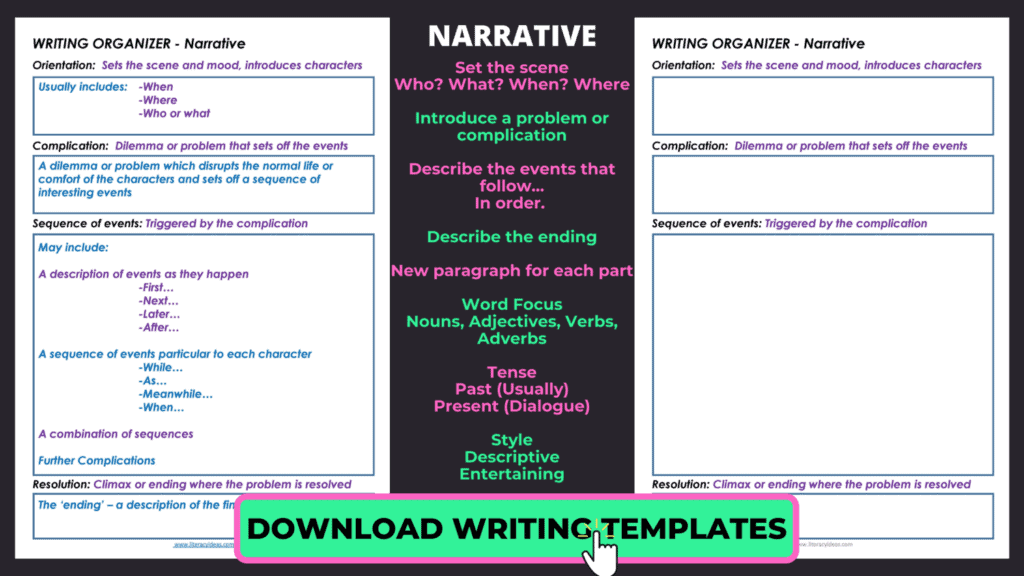

Now that we understand the story elements and how they come together to form stories, it’s time to start planning and writing your narrative.

In many cases, the template and guide below will provide enough details on how to craft a great story. However, if you still need assistance with the fundamentals of writing, such as sentence structure, paragraphs and using correct grammar, we have some excellent guides on those here.

USE YOUR WRITING TIME EFFECTIVELY: Maximize your narrative writing sessions by spending approximately 20 per cent of your time planning and preparing. This ensures greater productivity during your writing time and keeps you focused and on task.

Use tools such as graphic organizers to logically sequence your narrative if you are not a confident story writer. If you are working with reluctant writers, try using narrative writing prompts to get their creative juices flowing.

Spend most of your writing hour on the task at hand, don’t get too side-tracked editing during this time and leave some time for editing. When editing a narrative, examine it for these three elements.

- Spelling and grammar ( Is it readable?)

- Story structure and continuity ( Does it make sense, and does it flow? )

- Character and plot analysis. (Are your characters engaging? Does your problem/resolution work? )

1. SETTING THE SCENE: THE WHERE AND THE WHEN

The story’s setting often answers two of the central questions in the story, namely, the where and the when. The answers to these two crucial questions will often be informed by the type of story the student is writing.

The story’s setting can be chosen to quickly orient the reader to the type of story they are reading. For example, a fictional narrative writing piece such as a horror story will often begin with a description of a haunted house on a hill or an abandoned asylum in the middle of the woods. If we start our story on a rocket ship hurtling through the cosmos on its space voyage to the Alpha Centauri star system, we can be reasonably sure that the story we are embarking on is a work of science fiction.

Such conventions are well-worn clichés true, but they can be helpful starting points for our novice novelists to make a start.

Having students choose an appropriate setting for the type of story they wish to write is an excellent exercise for our younger students. It leads naturally onto the next stage of story writing, which is creating suitable characters to populate this fictional world they have created. However, older or more advanced students may wish to play with the expectations of appropriate settings for their story. They may wish to do this for comic effect or in the interest of creating a more original story. For example, opening a story with a children’s birthday party does not usually set up the expectation of a horror story. Indeed, it may even lure the reader into a happy reverie as they remember their own happy birthday parties. This leaves them more vulnerable to the surprise element of the shocking action that lies ahead.

Once the students have chosen a setting for their story, they need to start writing. Little can be more terrifying to English students than the blank page and its bare whiteness stretching before them on the table like a merciless desert they must cross. Give them the kick-start they need by offering support through word banks or writing prompts. If the class is all writing a story based on the same theme, you may wish to compile a common word bank on the whiteboard as a prewriting activity. Write the central theme or genre in the middle of the board. Have students suggest words or phrases related to the theme and list them on the board.

You may wish to provide students with a copy of various writing prompts to get them started. While this may mean that many students’ stories will have the same beginning, they will most likely arrive at dramatically different endings via dramatically different routes.

A bargain is at the centre of the relationship between the writer and the reader. That bargain is that the reader promises to suspend their disbelief as long as the writer creates a consistent and convincing fictional reality. Creating a believable world for the fictional characters to inhabit requires the student to draw on convincing details. The best way of doing this is through writing that appeals to the senses. Have your student reflect deeply on the world that they are creating. What does it look like? Sound like? What does the food taste like there? How does it feel like to walk those imaginary streets, and what aromas beguile the nose as the main character winds their way through that conjured market?

Also, Consider the when; or the time period. Is it a future world where things are cleaner and more antiseptic? Or is it an overcrowded 16th-century London with human waste stinking up the streets? If students can create a multi-sensory installation in the reader’s mind, then they have done this part of their job well.

Popular Settings from Children’s Literature and Storytelling

- Fairytale Kingdom

- Magical Forest

- Village/town

- Underwater world

- Space/Alien planet

2. CASTING THE CHARACTERS: THE WHO

Now that your student has created a believable world, it is time to populate it with believable characters.

In short stories, these worlds mustn’t be overpopulated beyond what the student’s skill level can manage. Short stories usually only require one main character and a few secondary ones. Think of the short story more as a small-scale dramatic production in an intimate local theater than a Hollywood blockbuster on a grand scale. Too many characters will only confuse and become unwieldy with a canvas this size. Keep it simple!

Creating believable characters is often one of the most challenging aspects of narrative writing for students. Fortunately, we can do a few things to help students here. Sometimes it is helpful for students to model their characters on actual people they know. This can make things a little less daunting and taxing on the imagination. However, whether or not this is the case, writing brief background bios or descriptions of characters’ physical personality characteristics can be a beneficial prewriting activity. Students should give some in-depth consideration to the details of who their character is: How do they walk? What do they look like? Do they have any distinguishing features? A crooked nose? A limp? Bad breath? Small details such as these bring life and, therefore, believability to characters. Students can even cut pictures from magazines to put a face to their character and allow their imaginations to fill in the rest of the details.

Younger students will often dictate to the reader the nature of their characters. To improve their writing craft, students must know when to switch from story-telling mode to story-showing mode. This is particularly true when it comes to character. Encourage students to reveal their character’s personality through what they do rather than merely by lecturing the reader on the faults and virtues of the character’s personality. It might be a small relayed detail in the way they walk that reveals a core characteristic. For example, a character who walks with their head hanging low and shoulders hunched while avoiding eye contact has been revealed to be timid without the word once being mentioned. This is a much more artistic and well-crafted way of doing things and is less irritating for the reader. A character who sits down at the family dinner table immediately snatches up his fork and starts stuffing roast potatoes into his mouth before anyone else has even managed to sit down has revealed a tendency towards greed or gluttony.

Understanding Character Traits

Again, there is room here for some fun and profitable prewriting activities. Give students a list of character traits and have them describe a character doing something that reveals that trait without ever employing the word itself.

It is also essential to avoid adjective stuffing here. When looking at students’ early drafts, adjective stuffing is often apparent. To train the student out of this habit, choose an adjective and have the student rewrite the sentence to express this adjective through action rather than telling.

When writing a story, it is vital to consider the character’s traits and how they will impact the story’s events. For example, a character with a strong trait of determination may be more likely to overcome obstacles and persevere. In contrast, a character with a tendency towards laziness may struggle to achieve their goals. In short, character traits add realism, depth, and meaning to a story, making it more engaging and memorable for the reader.

Popular Character Traits in Children’s Stories

- Determination

- Imagination

- Perseverance

- Responsibility

We have an in-depth guide to creating great characters here , but most students should be fine to move on to planning their conflict and resolution.

3. NO PROBLEM? NO STORY! HOW CONFLICT DRIVES A NARRATIVE

This is often the area apprentice writers have the most difficulty with. Students must understand that without a problem or conflict, there is no story. The problem is the driving force of the action. Usually, in a short story, the problem will center around what the primary character wants to happen or, indeed, wants not to happen. It is the hurdle that must be overcome. It is in the struggle to overcome this hurdle that events happen.

Often when a student understands the need for a problem in a story, their completed work will still not be successful. This is because, often in life, problems remain unsolved. Hurdles are not always successfully overcome. Students pick up on this.

We often discuss problems with friends that will never be satisfactorily resolved one way or the other, and we accept this as a part of life. This is not usually the case with writing a story. Whether a character successfully overcomes his or her problem or is decidedly crushed in the process of trying is not as important as the fact that it will finally be resolved one way or the other.

A good practical exercise for students to get to grips with this is to provide copies of stories and have them identify the central problem or conflict in each through discussion. Familiar fables or fairy tales such as Three Little Pigs, The Boy Who Cried Wolf, Cinderella, etc., are great for this.

While it is true that stories often have more than one problem or that the hero or heroine is unsuccessful in their first attempt to solve a central problem, for beginning students and intermediate students, it is best to focus on a single problem, especially given the scope of story writing at this level. Over time students will develop their abilities to handle more complex plots and write accordingly.

Popular Conflicts found in Children’s Storytelling.

- Good vs evil

- Individual vs society

- Nature vs nurture

- Self vs others

- Man vs self

- Man vs nature

- Man vs technology

- Individual vs fate

- Self vs destiny

Conflict is the heart and soul of any good story. It’s what makes a story compelling and drives the plot forward. Without conflict, there is no story. Every great story has a struggle or a problem that needs to be solved, and that’s where conflict comes in. Conflict is what makes a story exciting and keeps the reader engaged. It creates tension and suspense and makes the reader care about the outcome.

Like in real life, conflict in a story is an opportunity for a character’s growth and transformation. It’s a chance for them to learn and evolve, making a story great. So next time stories are written in the classroom, remember that conflict is an essential ingredient, and without it, your story will lack the energy, excitement, and meaning that makes it truly memorable.

4. THE NARRATIVE CLIMAX: HOW THINGS COME TO A HEAD!

The climax of the story is the dramatic high point of the action. It is also when the struggles kicked off by the problem come to a head. The climax will ultimately decide whether the story will have a happy or tragic ending. In the climax, two opposing forces duke things out until the bitter (or sweet!) end. One force ultimately emerges triumphant. As the action builds throughout the story, suspense increases as the reader wonders which of these forces will win out. The climax is the release of this suspense.

Much of the success of the climax depends on how well the other elements of the story have been achieved. If the student has created a well-drawn and believable character that the reader can identify with and feel for, then the climax will be more powerful.

The nature of the problem is also essential as it determines what’s at stake in the climax. The problem must matter dearly to the main character if it matters at all to the reader.

Have students engage in discussions about their favorite movies and books. Have them think about the storyline and decide the most exciting parts. What was at stake at these moments? What happened in your body as you read or watched? Did you breathe faster? Or grip the cushion hard? Did your heart rate increase, or did you start to sweat? This is what a good climax does and what our students should strive to do in their stories.

The climax puts it all on the line and rolls the dice. Let the chips fall where the writer may…

Popular Climax themes in Children’s Stories

- A battle between good and evil

- The character’s bravery saves the day

- Character faces their fears and overcomes them

- The character solves a mystery or puzzle.

- The character stands up for what is right.

- Character reaches their goal or dream.

- The character learns a valuable lesson.

- The character makes a selfless sacrifice.

- The character makes a difficult decision.

- The character reunites with loved ones or finds true friendship.

5. RESOLUTION: TYING UP LOOSE ENDS

After the climactic action, a few questions will often remain unresolved for the reader, even if all the conflict has been resolved. The resolution is where those lingering questions will be answered. The resolution in a short story may only be a brief paragraph or two. But, in most cases, it will still be necessary to include an ending immediately after the climax can feel too abrupt and leave the reader feeling unfulfilled.

An easy way to explain resolution to students struggling to grasp the concept is to point to the traditional resolution of fairy tales, the “And they all lived happily ever after” ending. This weather forecast for the future allows the reader to take their leave. Have the student consider the emotions they want to leave the reader with when crafting their resolution.

While the action is usually complete by the end of the climax, it is in the resolution that if there is a twist to be found, it will appear – think of movies such as The Usual Suspects. Pulling this off convincingly usually requires considerable skill from a student writer. Still, it may well form a challenging extension exercise for those more gifted storytellers among your students.

Popular Resolutions in Children’s Stories

- Our hero achieves their goal

- The character learns a valuable lesson

- A character finds happiness or inner peace.

- The character reunites with loved ones.

- Character restores balance to the world.

- The character discovers their true identity.

- Character changes for the better.

- The character gains wisdom or understanding.

- Character makes amends with others.

- The character learns to appreciate what they have.

Once students have completed their story, they can edit for grammar, vocabulary choice, spelling, etc., but not before!

As mentioned, there is a craft to storytelling, as well as an art. When accurate grammar, perfect spelling, and immaculate sentence structures are pushed at the outset, they can cause storytelling paralysis. For this reason, it is essential that when we encourage the students to write a story, we give them license to make mechanical mistakes in their use of language that they can work on and fix later.

Good narrative writing is a very complex skill to develop and will take the student years to become competent. It challenges not only the student’s technical abilities with language but also her creative faculties. Writing frames, word banks, mind maps, and visual prompts can all give valuable support as students develop the wide-ranging and challenging skills required to produce a successful narrative writing piece. But, at the end of it all, as with any craft, practice and more practice is at the heart of the matter.

TIPS FOR WRITING A GREAT NARRATIVE

- Start your story with a clear purpose: If you can determine the theme or message you want to convey in your narrative before starting it will make the writing process so much simpler.

- Choose a compelling storyline and sell it through great characters, setting and plot: Consider a unique or interesting story that captures the reader’s attention, then build the world and characters around it.

- Develop vivid characters that are not all the same: Make your characters relatable and memorable by giving them distinct personalities and traits you can draw upon in the plot.

- Use descriptive language to hook your audience into your story: Use sensory language to paint vivid images and sequences in the reader’s mind.

- Show, don’t tell your audience: Use actions, thoughts, and dialogue to reveal character motivations and emotions through storytelling.

- Create a vivid setting that is clear to your audience before getting too far into the plot: Describe the time and place of your story to immerse the reader fully.

- Build tension: Refer to the story map earlier in this article and use conflict, obstacles, and suspense to keep the audience engaged and invested in your narrative.

- Use figurative language such as metaphors, similes, and other literary devices to add depth and meaning to your narrative.

- Edit, revise, and refine: Take the time to refine and polish your writing for clarity and impact.

- Stay true to your voice: Maintain your unique perspective and style in your writing to make it your own.

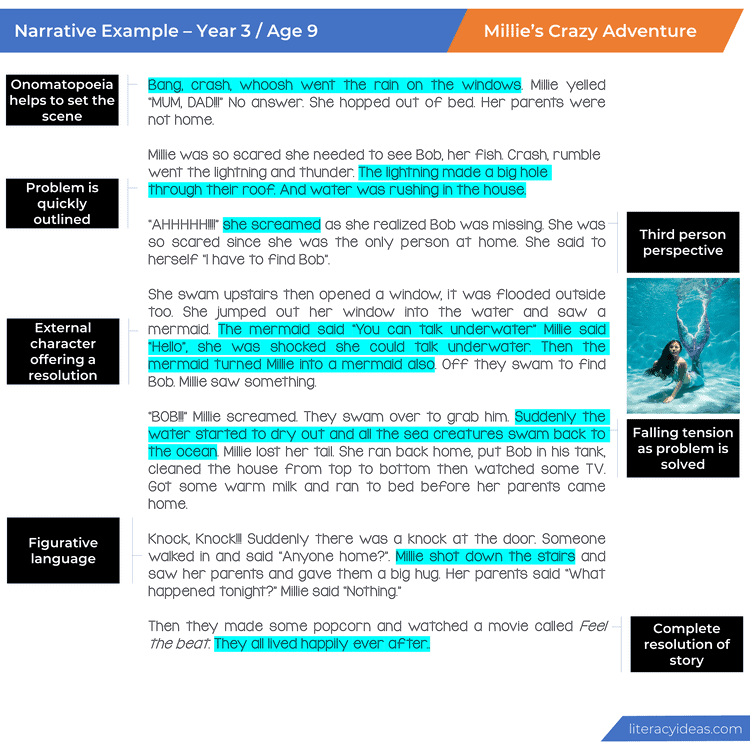

NARRATIVE WRITING EXAMPLES (Student Writing Samples)

Below are a collection of student writing samples of narratives. Click on the image to enlarge and explore them in greater detail. Please take a moment to read these creative stories in detail and the teacher and student guides which highlight some of the critical elements of narratives to consider before writing.

Please understand these student writing samples are not intended to be perfect examples for each age or grade level but a piece of writing for students and teachers to explore together to critically analyze to improve student writing skills and deepen their understanding of story writing.

We recommend reading the example either a year above or below, as well as the grade you are currently working with, to gain a broader appreciation of this text type.

NARRATIVE WRITING PROMPTS (Journal Prompts)

When students have a great journal prompt, it can help them focus on the task at hand, so be sure to view our vast collection of visual writing prompts for various text types here or use some of these.

- On a recent European trip, you find your travel group booked into the stunning and mysterious Castle Frankenfurter for a single night… As night falls, the massive castle of over one hundred rooms seems to creak and groan as a series of unexplained events begin to make you wonder who or what else is spending the evening with you. Write a narrative that tells the story of your evening.

- You are a famous adventurer who has discovered new lands; keep a travel log over a period of time in which you encounter new and exciting adventures and challenges to overcome. Ensure your travel journal tells a story and has a definite introduction, conflict and resolution.

- You create an incredible piece of technology that has the capacity to change the world. As you sit back and marvel at your innovation and the endless possibilities ahead of you, it becomes apparent there are a few problems you didn’t really consider. You might not even be able to control them. Write a narrative in which you ride the highs and lows of your world-changing creation with a clear introduction, conflict and resolution.

- As the final door shuts on the Megamall, you realise you have done it… You and your best friend have managed to sneak into the largest shopping centre in town and have the entire place to yourselves until 7 am tomorrow. There is literally everything and anything a child would dream of entertaining themselves for the next 12 hours. What amazing adventures await you? What might go wrong? And how will you get out of there scot-free?

- A stranger walks into town… Whilst appearing similar to almost all those around you, you get a sense that this person is from another time, space or dimension… Are they friends or foes? What makes you sense something very strange is going on? Suddenly they stand up and walk toward you with purpose extending their hand… It’s almost as if they were reading your mind.

NARRATIVE WRITING VIDEO TUTORIAL

Teaching Resources

Use our resources and tools to improve your student’s writing skills through proven teaching strategies.

When teaching narrative writing, it is essential that you have a range of tools, strategies and resources at your disposal to ensure you get the most out of your writing time. You can find some examples below, which are free and paid premium resources you can use instantly without any preparation.

FREE Narrative Graphic Organizer

THE STORY TELLERS BUNDLE OF TEACHING RESOURCES

A MASSIVE COLLECTION of resources for narratives and story writing in the classroom covering all elements of crafting amazing stories. MONTHS WORTH OF WRITING LESSONS AND RESOURCES, including:

NARRATIVE WRITING CHECKLIST BUNDLE

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ (92 Reviews)

OTHER GREAT ARTICLES ABOUT NARRATIVE WRITING

Narrative Writing for Kids: Essential Skills and Strategies

7 Great Narrative Lesson Plans Students and Teachers Love

Top 7 Narrative Writing Exercises for Students

How to Write a Scary Story

VIDEO COURSE

Finish your draft in our 3-month master class. Sign up now to watch a free lesson!

Learn How to Write a Novel

Finish your draft in our 3-month master class. Enroll now for daily lessons, weekly critique, and live events. Your first lesson is free!

Blog • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Feb 15, 2022

7 Elements of a Story: How to Create an Awesome Narrative

About tom bromley.

Author, editor, tutor, and bestselling ghostwriter. Tom Bromley is the head of learning at Reedsy, where he has created their acclaimed course, 'How to Write a Novel.'

If you're looking to turn an original idea into a story, you're in luck: thanks to the groundwork laid by storytellers over the years, we now know the secrets of creating an engaging narrative. You can turn the slightest concept into a gripping tale by mastering the seven essential elements of a story — theme, characters, setting, plot, conflict, point of view, and style.

To help you better understand how stories come together , here are seven elements you'll find in almost any story:

Story Element #1: Theme

Story element #2: characters, story element #3: setting, story element #4: plot, story element #5: conflict, story element #6: point of view, story element #7: style.

Before you can work out what’s driving your characters or your plot, it helps to know what’s driving you to write this story in the first place. Is there an overarching lesson or message you want to get across? Are you looking to evoke a certain feeling?

A clear, artfully deployed theme will elevate your story beyond the sum of its parts and help it stick in the minds of your readers. Make sure you give those readers some credit, though: instead of spelling it out, weave aspects of your theme into other elements of your story and let them discover it on their own.

Learn more:

- What is the Theme of a Story? ( Guide )

Your characters give your story the depth it needs to keep readers wanting more — they are, quite literally, the life force of your story. Their personalities and interactions with one another will naturally create conflict and drive your story forward.

Well-crafted characters will also make your story more relatable. If your readers can imagine themselves in your characters’ shoes — or recognize aspects of characters’ personalities in people they know — they’ll develop a stronger connection with your story as a whole.

FREE RESOURCE

Reedsy’s Character Profile Template

A story is only as strong as its characters. Fill this out to develop yours.

The setting is the world in which your story will take place — this includes the broader locations and time, as well as more specific details like your characters’ school or workplace. You’ll often see writers transplant well-known plots into a new setting ( Romeo & Juliet in Space! Cinderella in 1960s Brooklyn!). Whenever this happens, the new environment always finds a way to influence and adapt the story into something new.

While rich setting descriptions will captivate your readers, it’s important not to bore them with paragraphs upon paragraphs of pure description. As with the theme, weaving exposition into your story little by little will allow the reader to gradually create a mental image of your fictional world as the story unfolds, making for a much more immersive experience.

- Setting of a Story: What Is It? And How to Write It ( Click here )

- Worldbuilding: the Master Guide (with Template) ( Click here )

Now we’re getting to the main event — the plot, aka the things that actually happen in your story. In almost all genres (the exception being literary fiction), as your story progresses, the stakes for your protagonist escalate and lead to an inevitable climax.

If your plot comes across as a sequence of random events, your readers will tend to get bored or confused

This happened, then this happened, and then THIS also happened.

Instead, each point of your plot must happen as a result of a character's actions.

This happened, therefore that happened, which then caused THIS to happen.

This pattern of "cause and effect" induces a sense of intrigue and suspense, making the audience want to find out what happens next .

Get our Book Development Template

Use this template to go from a vague idea to a solid plan for a first draft.

- What is Plot? An Author's Guide to Storytelling ( Click here )

- Story Structure: 7 Narrative Structures All Writers Should Know ( Click here )

- Rising Action: Where the Story Really Happens (With Examples) ( Click here )

We mentioned rising stakes just now — the reason underlying this tension is your story’s conflict. Whether the source of this conflict is external, like an unyielding antagonist, or internal, like a moral struggle for your main character , it’ll be one of the most important elements of your story. Conflict creates tension by giving your protagonist some sense of purpose. It gets readers invested in the story, encouraging them to keep turning the page.

If you're still not convinced, remember that every story always asks the same question:

Will the protagonist overcome their obstacles to get what they want?

In other words, conflict is story.

- Internal vs External Conflict: How Conflict Drives a Story ( Click here )

- How to Create Conflict in a Story (with 6 Simple Questions) ( Click here )

Your book’s point of view is the perspective from which the story is told. You’ve got a few options here, all of which have different impacts on the overall tone of your story. A close viewpoint like first person will feel more intimate while ones that hold the protagonist at arm’s length (such as third person omniscient) may feel more objective and formal.

FREE COURSE

Understanding Point of View

Learn to master different POVs and choose the best for your story.

The character you choose for your book’s POV can also determine the arc of the entire narrative. Take a murder mystery novel: telling the story through the viewpoint of the murderer will be drastically different than if it had been seen through the detective's eyes.

By choosing an unusual viewpoint character, you can completely upend how your plot unfolds, the central conflict, and how your audience sympathizes with certain characters.

- Point of View: The Ultimate POV Guide — with Examples ( Click here )

- Free Course: Understanding Point of View ( Click here )

Which POV is right for your book?

Take our quiz to find out! Takes only 1 minute.

Your writing style is the culmination of all the features that make your storytelling so unique — that’s everything from your pacing and tone to the specific words or phrases you use. While reflection and deliberation can help you refine your style, there really aren’t any particular criteria to determine what “good” prose means.

Take Ernest Hemmingway and Toni Morrison, two of America’s most celebrated authors — their writing styles couldn’t be more different. Hemmingway is known for his concise and straightforward prose, invoking scenes with a few sparse sentences. On the other hand, Morrison leans more towards rich and vivid imagery that relishes in the language. This goes to show that no style is better than another — as long as you’re being true to yourself, your personality will shine through and make your story one to be remembered.

- 45+ Literary Devices and Terms Everybody Should Know ( Click here )

- Video: How to Find Your Author Voice ( Click here )

So there you have it, seven essential story elements that any narrative can’t live without. Bear these in mind as you work on your book, and you’ll be a master storyteller in no time!

If you’re ready to take your story to the next level, check out our guide to professional editing to help you work out your next steps.

Continue reading

Recommended posts from the Reedsy Blog

100+ Character Ideas (and How to Come Up With Your Own)

Character creation can be challenging. To help spark your creativity, here’s a list of 100+ character ideas, along with tips on how to come up with your own.

How to Introduce a Character: 8 Tips To Hook Readers In

Introducing characters is an art, and these eight tips and examples will help you master it.

450+ Powerful Adjectives to Describe a Person (With Examples)

Want a handy list to help you bring your characters to life? Discover words that describe physical attributes, dispositions, and emotions.

How to Plot a Novel Like a NYT Bestselling Author

Need to plot your novel? Follow these 7 steps from New York Times bestselling author Caroline Leavitt.

How to Write an Autobiography: The Story of Your Life

Want to write your autobiography but aren’t sure where to start? This step-by-step guide will take you from opening lines to publishing it for everyone to read.

What is the Climax of a Story? Examples & Tips

The climax is perhaps a story's most crucial moment, but many writers struggle to stick the landing. Let's see what makes for a great story climax.

Join a community of over 1 million authors

Reedsy is more than just a blog. Become a member today to discover how we can help you publish a beautiful book.

Bring your stories to life

Our free writing app lets you set writing goals and track your progress, so you can finally write that book!

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Enter your email or get started with a social account:

Elements of Creative Writing

(3 reviews)

J.D. Schraffenberger, University of Northern Iowa

Rachel Morgan, University of Northern Iowa

Grant Tracey, University of Northern Iowa

Copyright Year: 2023

ISBN 13: 9780915996179

Publisher: University of Northern Iowa

Language: English

Formats Available

Conditions of use.

Learn more about reviews.

Reviewed by Colin Rafferty, Professor, University of Mary Washington on 8/2/24

Fantastically thorough. By using three different authors, one for each genre of creative writing, the textbook allows for a wider diversity of thought and theory on writing as a whole, while still providing a solid grounding in the basics of each... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 5 see less

Fantastically thorough. By using three different authors, one for each genre of creative writing, the textbook allows for a wider diversity of thought and theory on writing as a whole, while still providing a solid grounding in the basics of each genre. The included links to referred texts also builds in an automatic, OER-based anthology for students. Terms are not only defined clearly, but also their utility is explained--here's what assonance can actually do in a poem, rather than simply "it's repeated vowel sounds,"

Content Accuracy rating: 5

Calling the content "accurate" requires a suspension of the notion that art and writing aren't subjective; instead, it might be more useful to judge the content on the potential usefulness to students, in which case it' s quite accurate. Reading this, I often found myself nodding in agreement with the authors' suggestions for considering published work and discussing workshop material, and their prompts for generating creative writing feel full of potential. It's as error-free, if not more so, than most OER textbooks (which is to say: a few typos here and there) and a surprising number of trade publications. It's not unbiased, per se--after all, these are literary magazine editors writing the textbook and often explaining what it is about a given piece of writing that they find (or do not find) engaging and admirable--but unbiased isn't necessarily a quantity one looks for in creative writing textbooks.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 4

The thing about creative writing is that they keep making more of it, so eventually the anthology elements of this textbook will be less "look what's getting published these days" and more "look what was getting published back then," but the structure of the textbook should allow for substitution and replacement (that said, if UNI pulls funding for NAR, as too many universities are doing these days, then the bigger concern is about the archive vanishing). The more rhetorical elements of the textbook are solid, and should be useful to students and faculty for a long time.

Clarity rating: 5

Very clear, straightforward prose, and perhaps more importantly, there's a sense of each author that emerges in each section, demonstrating to students that writing, especially creative writing, comes from a person. As noted above, any technical jargon is not only explained, but also discussed, meaning that how and why one might use any particular literary technique are emphasized over simply rote memorization of terms.

Consistency rating: 4

It's consistent within each section, but the voice and approach change with each genre. This is a strength, not a weakness, and allows the textbook to avoid the one-size-fits-all approach of single-author creative writing textbooks. There are different "try this" exercises for each genre that strike me as calibrated to impress the facets of that particular genre on the student.

Modularity rating: 5

The three-part structure of the book allows teachers to start wherever they like, genre-wise. While the internal structure of each section does build upon and refer back to earlier chapters, that seems more like an advantage than a disadvantage. Honestly, there's probably enough flexibility built into the textbook that even the callbacks could be glossed over quickly enough in the classroom.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 5

Chapters within each genre section build upon each other, starting with basics and developing the complexity and different elements of that genre. The textbook's overall organization allows some flexibility in terms of starting with fiction, poetry, or nonfiction.

Interface rating: 4

Easy to navigate. I particularly like the way that links for the anthology work in the nonfiction section (clearly appearing at the side of the text in addition to within it) and would like to see that consistently applied throughout.

Grammatical Errors rating: 5

A few typos here and there, but you know what else generally has a few typos here and there? Expensive physical textbooks.

Cultural Relevance rating: 5

The anthology covers a diverse array of authors and cultural identities, and the textbook authors are not only conscious of their importance but also discuss how those identities affect decisions that the authors might have made, even on a formal level. If you find an underrepresented group missing, it should be easy enough to supplement this textbook with a poem/essay/story.

Very excited to use this in my Intro to CW classes--unlike other OERs that I've used for the field, this one feels like it could compete with the physical textbooks head-to-head. Other textbooks have felt more like a trade-off between content and cost.

Reviewed by Jeanne Cosmos, Adjunct Faculty, Massachusetts Bay Community College on 7/7/24

Direct language and concrete examples & Case Studies. read more

Direct language and concrete examples & Case Studies.

References to literature and writers- on track.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 5

On point for support to assist writers and creative process.

Direct language and easy to read.

First person to third person. Too informal in many areas of the text.

Units are readily accessible.

Process of creative writing and prompts- scaffold areas of learning for students.

Interface rating: 5

No issues found.

The book is accurate in this regard.

Cultural Relevance rating: 4

Always could be revised and better.

Yes. Textbook font is not academic and spacing - also not academic. A bit too primary. Suggest- Times New Roman 12- point font & a space plus - Some of the language and examples too informal and the tone of lst person would be more effective if - direct and not so 'chummy' as author references his personal recollections. Not effective.

Reviewed by Robert Moreira, Lecturer III, University of Texas Rio Grande Valley on 3/21/24

Unlike Starkey's CREATIVE WRITING: FOUR GENRES IN BRIEF, this textbook does not include a section on drama. read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 4 see less

Unlike Starkey's CREATIVE WRITING: FOUR GENRES IN BRIEF, this textbook does not include a section on drama.

As far as I can tell, content is accurate, error free and unbiased.

The book is relevant and up-to-date.

The text is clear and easy to understand.

Consistency rating: 5

I would agree that the text is consistent in terms of terminology and framework.

Text is modular, yes, but I would like to see the addition of a section on dramatic writing.

Topics are presented in logical, clear fashion.

Navigation is good.

No grammatical issues that I could see.

Cultural Relevance rating: 3

I'd like to see more diverse creative writing examples.

As I stated above, textbook is good except that it does not include a section on dramatic writing.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter One: One Great Way to Write a Short Story

- Chapter Two: Plotting

- Chapter Three: Counterpointed Plotting

- Chapter Four: Show and Tell

- Chapter Five: Characterization and Method Writing

- Chapter Six: Character and Dialouge

- Chapter Seven: Setting, Stillness, and Voice

- Chapter Eight: Point of View

- Chapter Nine: Learning the Unwritten Rules

- Chapter One: A Poetry State of Mind

- Chapter Two: The Architecture of a Poem

- Chapter Three: Sound

- Chapter Four: Inspiration and Risk

- Chapter Five: Endings and Beginnings

- Chapter Six: Figurative Language

- Chapter Seven: Forms, Forms, Forms

- Chapter Eight: Go to the Image

- Chapter Nine: The Difficult Simplicity of Short Poems and Killing Darlings

Creative Nonfiction

- Chapter One: Creative Nonfiction and the Essay

- Chapter Two: Truth and Memory, Truth in Memory

- Chapter Three: Research and History

- Chapter Four: Writing Environments

- Chapter Five: Notes on Style

- Chapter Seven: Imagery and the Senses

- Chapter Eight: Writing the Body

- Chapter Nine: Forms

Back Matter

- Contributors

- North American Review Staff

Ancillary Material

- University of Northern Iowa

About the Book

This free and open access textbook introduces new writers to some basic elements of the craft of creative writing in the genres of fiction, poetry, and creative nonfiction. The authors—Rachel Morgan, Jeremy Schraffenberger, and Grant Tracey—are editors of the North American Review, the oldest and one of the most well-regarded literary magazines in the United States. They’ve selected nearly all of the readings and examples (more than 60) from writing that has appeared in NAR pages over the years. Because they had a hand in publishing these pieces originally, their perspective as editors permeates this book. As such, they hope that even seasoned writers might gain insight into the aesthetics of the magazine as they analyze and discuss some reasons this work is so remarkable—and therefore teachable. This project was supported by NAR staff and funded via the UNI Textbook Equity Mini-Grant Program.

About the Contributors

J.D. Schraffenberger is a professor of English at the University of Northern Iowa. He is the author of two books of poems, Saint Joe's Passion and The Waxen Poor , and co-author with Martín Espada and Lauren Schmidt of The Necessary Poetics of Atheism . His other work has appeared in Best of Brevity , Best Creative Nonfiction , Notre Dame Review , Poetry East , Prairie Schooner , and elsewhere.

Rachel Morgan is an instructor of English at the University of Northern Iowa. She is the author of the chapbook Honey & Blood , Blood & Honey . Her work is included in the anthology Fracture: Essays, Poems, and Stories on Fracking in American and has appeared in the Journal of American Medical Association , Boulevard , Prairie Schooner , and elsewhere.

Grant Tracey author of three novels in the Hayden Fuller Mysteries ; the chapbook Winsome featuring cab driver Eddie Sands; and the story collection Final Stanzas , is fiction editor of the North American Review and an English professor at the University of Northern Iowa, where he teaches film, modern drama, and creative writing. Nominated four times for a Pushcart Prize, he has published nearly fifty short stories and three previous collections. He has acted in over forty community theater productions and has published critical work on Samuel Fuller and James Cagney. He lives in Cedar Falls, Iowa.

Contribute to this Page

COMMENTS

Narrative writing is the act of crafting a written narrative (or story), real or imagined. Here are a few different types of written narratives: Novels, films, television shows, and plays are narratives.

Master the art of storytelling with engaging narrative writing techniques. Create captivating narratives that captivate readers and ignite imagination.

You can turn the slightest concept into a gripping tale by mastering the seven essential elements of a story — theme, characters, setting, plot, conflict, point of view, and style. Revealed: the seven essential ingredients used in every story. Click to tweet!

This free and open access textbook introduces new writers to some basic elements of the craft of creative writing in the genres of fiction, poetry, and creative nonfiction.

At its core, narrative technique is the way in which a writer conveys what they want to say to their reader and the methods that they use to develop a story. The individual elements of different narrative techniques can be broken down into six distinct categories: Character. Perspective. Plot. Setting. Style. Theme.

Narrative writing is, essentially, story writing. A narrative can be fiction or nonfiction, and it can also occupy the space between these as a semi-autobiographical story, historical fiction, or a dramatized retelling of actual events.